Queen Victoria would comfortably eat six courses and come back for seconds

When entertaining Queen Victoria, the host provided the food, the staff and the dining room, then made themselves scarce, which was probably a blessing, writes David Lister

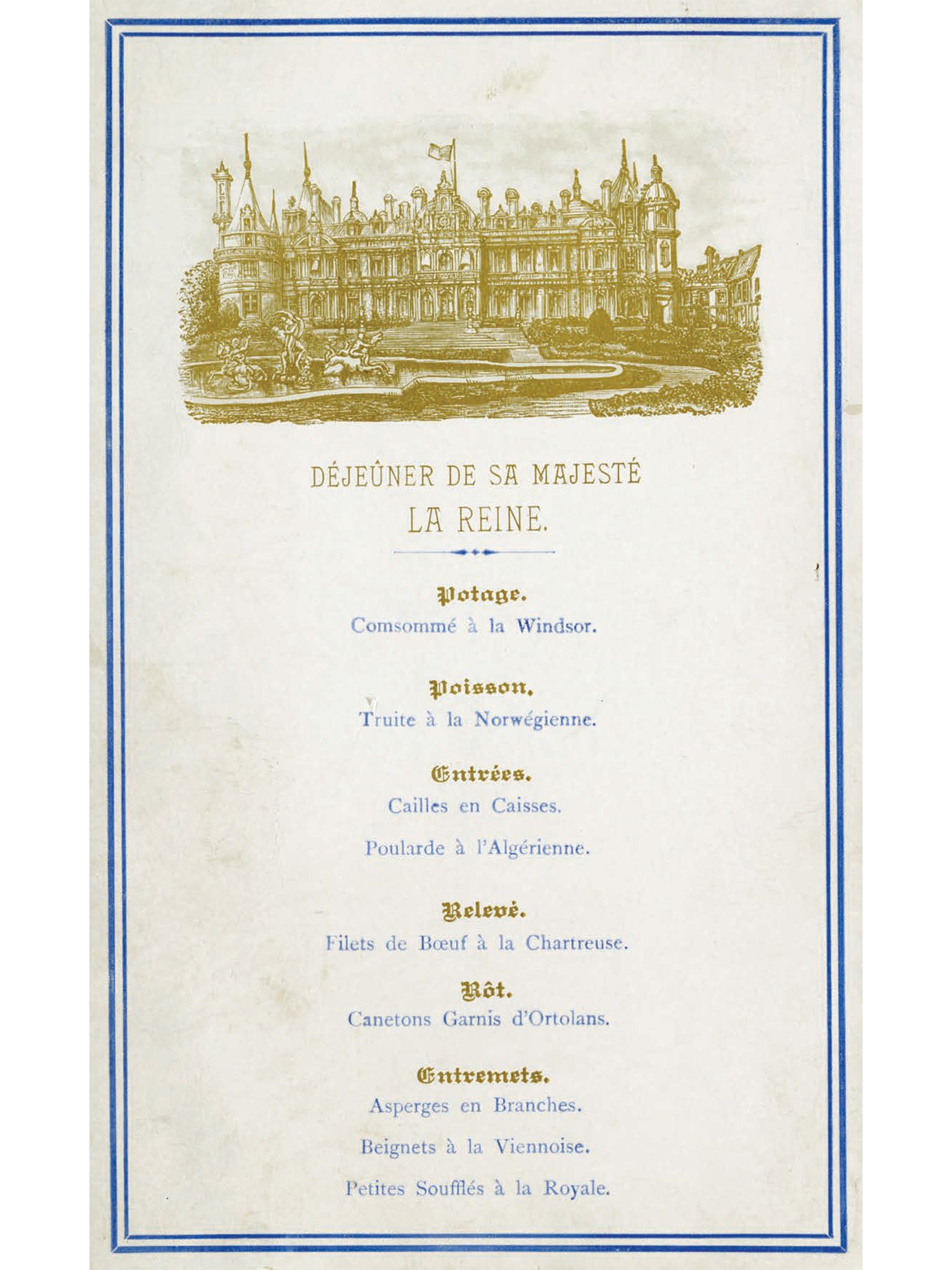

When Queen Victoria went for lunch at Waddesdon Manor, the Buckinghamshire home of the Rothschilds, she didn’t stint herself. The Queen enjoyed six courses over several hours, starting with consommé, then trout, followed by quails, beef and chicken, ducklings garnished with buntings and asparagus, Soufflés a la Royale (decorated with gold leaf) and Beignets a la Viennoise. She was also served ortolans, tiny roasted songbirds. Ortolan hunting is, of course, banned these days. But in the late 19th century those tiny songbirds were considered a delicacy.

And to ease the digestion, a military band played throughout the proceedings.

It seems that a rule for hosting the Queen was that you provided the food, the staff and the dining room, then made yourself scarce. The Queen insisted on dining in private with her daughters during that visit on 13 May 1890. Her host Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild and the other guests dined in the nearby breakfast room. That was probably a good thing, as Ferdinand didn’t share the Queen’s appetite. His luncheon consisted of cold toast and water.

Read More:

It's particularly fortunate for later generations that Ferdinand kept not just a visitors’ book but notes of his thoughts on this visit, and also, even back in 1890, a photo album. Of Queen Victoria he observed: “The royal appetite is proverbial, and it was not until about half past three that the Queen…reappeared.” His butler kept his eyes open and reported to him that Her Majesty had returned to the cold beef for a second helping.

Indeed, so satisfied was Queen Victoria that she sent her own chef to learn techniques from the Waddesdon kitchen. But while she loved the food, she was less impressed with one of Waddesdon's new-fangled inventions. Baron Ferdinand had installed a passenger lift for Queen Victoria’s visit (still on view at the stately home). No fan of the magic of electricity, she refused to ride in it.

Waddesdon Manor is a French-style Renaissance chateau with striking Victorian gardens containing classical sculptures and an ornate, working aviary, and inside an array of Old Master paintings in its 40 rooms. It is now a National Trust property but still serves as a private home for the Rothschild family. It was built by Baron Ferdinand, largely as a place to entertain and display his art collection, and after its completion in 1883 quickly gained a reputation among high society for its lavish meals and weekend house parties, sometimes accompanied by hunting, and regularly attended by international royalty and the Prince of Wales (the future Edward the Seventh).

A new online exhibition gives details of Queen Victoria’s visit among a plethora of information, objects and photographs, including the menus and the striking crockery of the time and of later years. It also gives glimpses of life upstairs and downstairs.

The fascinating thing about Ferdinand’s guest lists is that they included not just members of the royal family and British aristocracy, but also artists and writers. Louise Jopling, one of the few well-known female portrait painters of the day, was one visitor. Even more illustrious figures from the art and literary worlds included the pre-Raphaelite painter Sir John Everett Millais. And one party in August 1886 was attended by both Henry James and Guy de Maupassant. Oh to have been a fly on the wall at that gathering.

But even the royal and renowned could throw a hissy fit. On 10 July 1889 the Shah of Persia arrived at Waddesdon, and discovering that the Prince of Wales was not present and had sent his two sons in his place, the Shah withdrew to his room in a sulk and refused to come out until he was tempted by the promise of a conjurer.

The following morning his highlight in a tour of the house was the 18th century automatron in the form of a jewelled elephant, which apparently had to be played for him again and again before he could be distracted.

Catherine Taylor, head of archives and record at Waddesdon, points out that the work ethic of the staff is highlighted in some of the documents that have been passed down over the past 100 years and more. She says the Countess of Warwick arrived in a storm and said that “on rising early the next morning I saw an army of gardeners at work, taking out the damaged plants and putting in new ones that had been brought from the glass-houses in pots… After breakfast that morning I went into the grounds. The gardens were completely transformed! Not a damaged plant was to be seen anywhere. Also the small army of gardeners I had watched earlier in the morning had vanished, leaving behind them a new garden.”

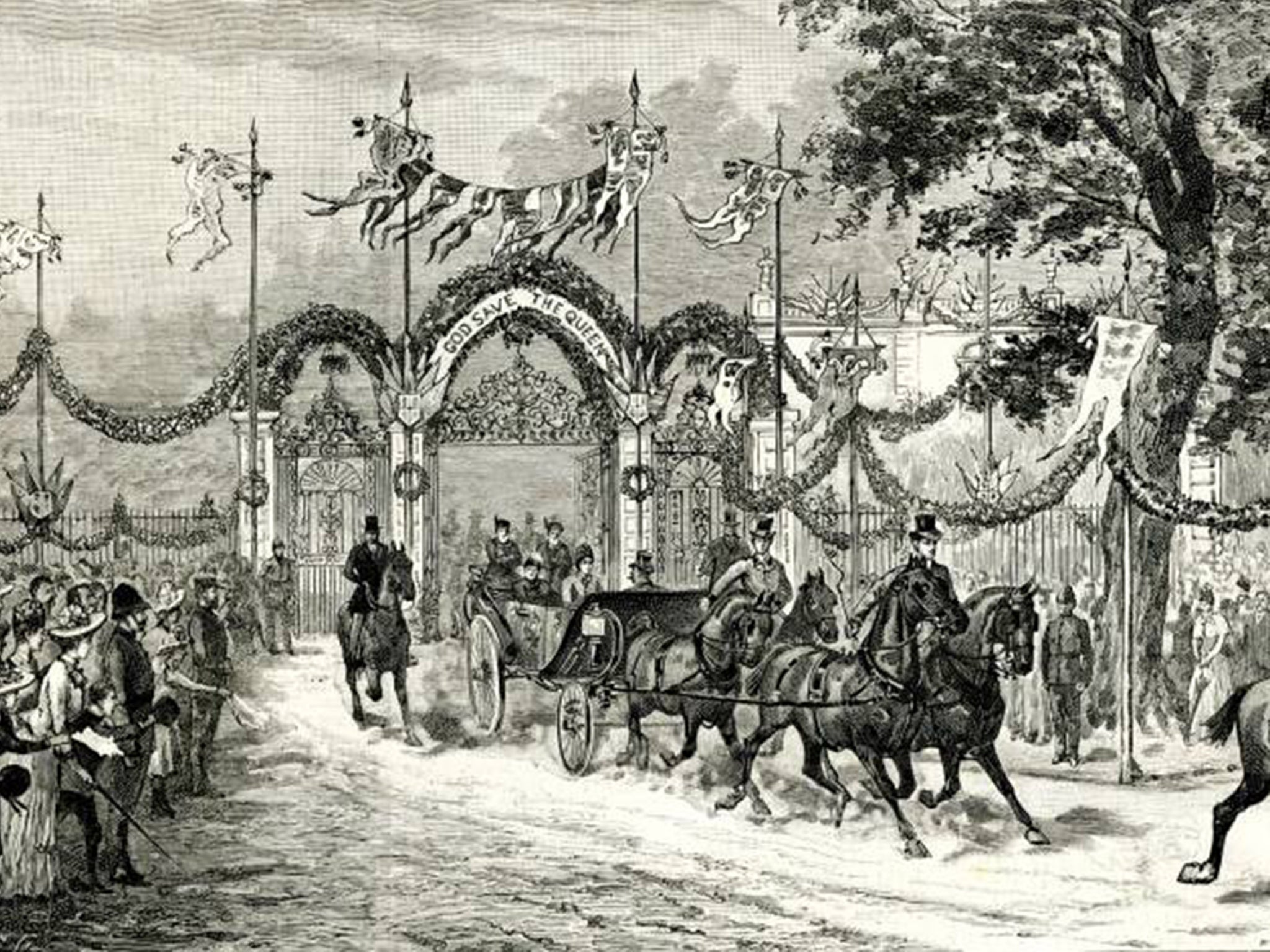

The visit by Queen Victoria clearly gave rise to some angst. According to the Bucks Herald at the time, the weather was the subject of significant levels of anxiety in the days leading up to Queen Victoria’s visit, having turned unseasonably cold and gloomy. This clearly worried Ferdinand, who claimed that “a barometer has rarely been consulted so often or so anxiously as that at Waddesdon on the day preceding Her Majesty’s visit”.

Queen Victoria arrived in Aylesbury at just after 11am on Wednesday 14 May 1890, and crowds gathered as the procession made its way from the station. The spontaneous outburst of enthusiasm which greeted the procession was reported as being “stirring and effective in the utmost degree”, no doubt helped by the efforts made by the people of Aylesbury to decorate the route with arches, banners and flags. But the people of Buckinghamshire were nothing if not thrifty. Ferdinand employed his waspish pen to note that the flags and banners were obtained cheaply, as they were recycled from Jubilee celebrations.

The Bucks Herald showed no such cynicism, reporting that “the children, with banners and flags flying, formed a very pretty picture, and as the Queen came into sight the National Anthem was sung with great spirit. The Queen drove slowly through the town, bowing to her cheering subjects, and Waddesdon was safely reached.”

Ferdinand’s musings tend to offer a less deferential and more whimsical perspective. He notes that after the lengthy luncheon, Queen Victoria retired to the State Apartments, giving him a moment of respite in which he smoked a cigar with Prince Henry of Battenberg. But he describes having to “throw away the fragrant weed unfinished, being bitterly railed by my relations who said I should be reeking of smoke when Her Majesty came down”.

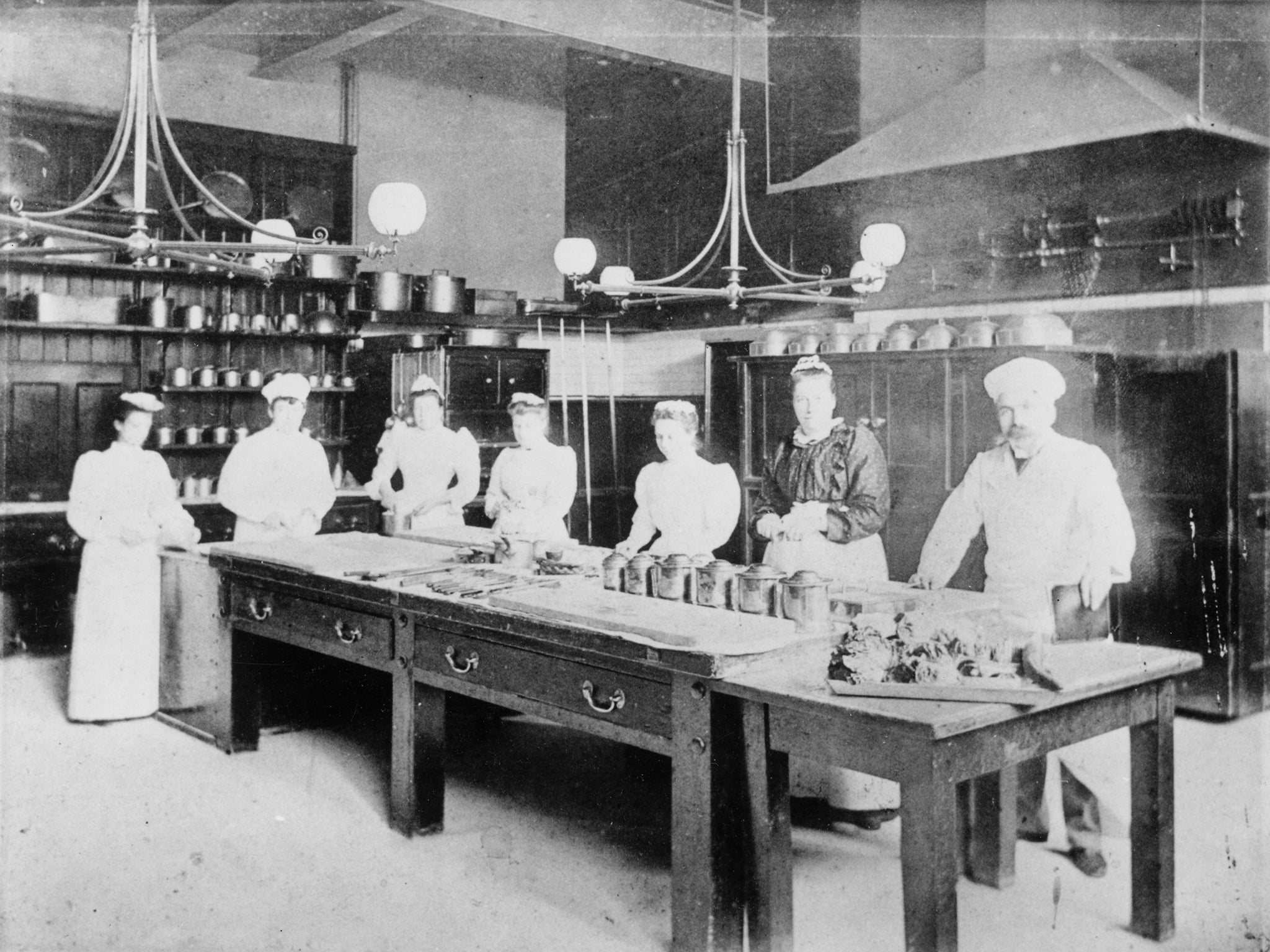

Waddesdon’s online exhibition also gives a picture of the servants’ quarters. The main kitchen, for example, formed part of a wider complex of domestic areas, including a larder, confectionery room, stillroom and scullery. In the basement below was a bake house, butcher’s shop, coal cellar, knife room and cellars for beer and wine.

In the early 1890s, just 24 staff ran the house, but this number could double when Ferdinand was hosting a party, and his French chef and Italian pastry-chef came down from London. Ferdinand lived with his sister, Alice, to whom he bequeathed the house on his death.

Kitchen staff included the cook, a kitchen maid, two scullery maids and two stillroom maids. Ferdinand’s French chef, Auguste Chalanger, and his confectioner, Arthur Chategner, travelled between Waddesdon and his London home.

The exhibition shows the range of copper pans and utensils lining the shelves, which formed part of the original batterie de cuisine used in the kitchens. The term “battery” originally referred to the process of hammering wares from sheet metal. The set comprises shallow sauté pans for frying, larger stewpans for boiling vegetables and smaller pans for sauces and glazes. Meat would have been turned on a spit. Other objects include hot water baths (bain-maries) for gently simmering delicate sauces and the large kite-shaped turbot kettle, which allowed the fish to be cooked whole. On the top shelf of the dresser can be seen an assortment of shaped dessert moulds for jelly and blancmange and ring moulds for main dishes. The inside of each pan, as well as many of the rims, are lined with tin to guard against the bad taste and toxic verdigris produced by copper.

In 1922 James and Dorothy de Rothschild inherited Waddesdon. Dorothy also turned out to be a good note-taker, with many reminiscences of life there in the 1920s. She notes how the kitchen shelves “… bore row upon row of shining copper pans. Variously shaped for every culinary purpose, and in every size, each of these bore a monogram – FR on the older ones, and AR on the more modern.” Some are further inscribed W for Waddesdon and L for London. She also emphasised how “some of the coppers needed two people to carry them, even when they were empty…” and observed that the staff were “possessed of immense physical strength”.

Much of the food prepared in the kitchens was grown and produced on the surrounding estate, with a large number of heated glasshouses (now demolished) providing out-of-season produce. Milk was provided by a herd of cows at the nearby dairy.

Dorothy also chronicled changes to the world of domestic service, noting on one occasion: “The pastry cook had departed and the numbers in each department were diminished.” She also recalled how a maid had intimated to her the hierarchy below stairs: “She gave me a mouth-watering description of the scones, jams and tisanes [herbal teas] which had been made in the still-room and ended by saying 'And, of course, we washed and prepared the parsley for the sandwiches – but naturally, we did not make the sandwiches themselves; that was kitchen work’.”

Standards were clearly high at Waddesdon, even down to how the fruit was grown. Baron Ferdinand’s sister, Alice, who inherited the property upon his death in 1898, regularly gave detailed instruction to her head gardener George F Johnson.

In a letter dated December 1906 she mentioned that “plums can be watered with chalky water, but no other fruit trees, and you had better find out before you use much Chiltern water for the pot plums whether it contains anything injurious to plum trees”. Garden historian Sophie Piebenga says Alice even required Johnson to change the soil as ‘[all] fruit grown for my table ought to be grown in the right soil. The pure Waddesdon soil, even the best Waddesdon loam, gives an acid taste to fruit and makes vegetables hard”.

Read More:

But the instructions were not all one way, from master or mistress to servant. James and Dorothy de Rothschild had a personal chef, Maurice Tissot, who served them as chef for 50 years. Tissot trained at the Café Royal and Ritz in London where he met James and was invited to begin work in 1928. He travelled between London and Waddesdon with the Rothschilds and became a close confidant. Dorothy passed on the individual likes and dislikes of her guests. The 6th Earl of Rosebery apparently commended Tissot’s curries in particular. But it was Tissot who advised Dorothy in culinary matters. He wrote her one letter with no-nonsense instructions on the proper preparation of coffee.

“It is a good point,” he wrote, “to buy the coffee in small amounts so as to use coffee that is freshly roasted and it should be kept in an air-tight tin so as to preserve its aroma.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks