Waking the dead in a Dickensian workhouse

Archaeologists are digging up the cemetery behind the Strand Union workhouse in Camden – and the remains reveal some grim secrets about the way Victorian society viewed the poor. Sean Russell finds those attitudes haven’t changed much

In 1856, after an outbreak of cholera had decimated his general practice, 36-year-old Joseph Rogers took a job as the medical officer at the Strand Union workhouse on Cleveland Street in Camden. He had been practicing medicine for 14 years but had never once stepped foot in a workhouse.

“Could I have foreseen what was in store for me,” he wrote in his book, Reminiscences of a Workhouse Medical Officer. “I question whether I should have applied for the appointment at all, but, having been appointed, I resolved to try it for a time at least.”

The workhouse was an intimidating, hulking, red-brick building which could well have been a prison, and on the front was inscribed the motto, and perhaps message for the poor: “Avoid idleness and intemperance.”

Inside the H-shaped building, Dr Rogers found that there were more than 500 inhabitants: the destitute, the old, the sick, the disabled, the mentally ill and the wretched. He discovered that the nurses there to help him were workhouse residents themselves and were often drunk; and that the male “insane ward” was located directly beneath the women’s infirmary dormitory. The air was filled with great clouds of dust and the stench from the dining room was overwhelming.

"If we had a troublesome or noisy lunatic in the ward,” Dr Rogers wrote, “it must have been anything but a comfort to the lying-in women above. But then neither their interests, nor the feelings of any of the other inmates, were at that time officially considered by the guardians, by the Poor Law inspectors, nor by any one else.”

Dr Rogers began his struggle against the master and the guardians of the workhouse, demanding improvements. He pushed for a humane diet for the inhabitants that was more than just gruel. This request was denied but he was informed he could feed the patients in the infirmary whatever he wished, a power he “did not hesitate to use”.

But the problem of overcrowding was a terrible strain on the young doctor, and he needed more space to care for the patients. He decided to move the laundry from the basement below the dining room to the backyard. This would free up space and eliminate the foul odours from the pauper’s linen that filled the dining room and caused such a terrible environment for the workers.

He was able to persuade the guardians to build a new one, which cost £400 (approximately £44,000 today). But as work began, Rogers stumbled across something buried in the ground.

“On proceeding to dig out the foundation,” he wrote, “the workmen came upon a number of skeletons… So full was this yard of human remains, that the contractor was compelled to go down 20 feet all round, before a foundation for the laundry could be obtained.” The workmen had cut right though the workhouse burial ground, which had been closed in 1853, just three years before Rogers arrived.

In 2020, archaeologists from Iceni Projects and L–P : Archaeology arrived at the workhouse to excavate that very same burial ground; the cemetery of the Georgian and Victorian poor of the parish of St Paul, Covent Garden.

It was September, the sky was overcast, and rain fell lightly on the mud. The workhouse loomed above but was shrouded by scaffolding as development continued. Below, in the shadow of the building, were several gazebos and, beneath them, archaeologists on their knees scraping gently at the soil or shovelling large lumps into wheelbarrows. As I got closer, I caught a glimpse of a skull and then some teeth – eye sockets looked out from the soil. The very top of the skull had been removed, but not by the archaeologist. It was cut cleanly and precisely by a surgeon’s hand, this person had been dissected before burial.

“It’s strange to be the first person touching a burial site after such a long time and to see how delicate the human skeleton is,” said Joanna Hameed, an archaeologist working on site for L–P : Archaeology. “It’s only natural to think about the people we are excavating and their personal lives.”

These people were rounded up and incarcerated and these are their mortal remains which were so horrendously treated

The Strand Union workhouse – or Covent Garden workhouse as it was originally known – was built in 1778. The land was leased to the parish of St Paul, Covent Garden, which sought new provisions for the care of the poor, with the obligation that some of the land was also consecrated for use as a cemetery, for the workhouse as well as an “overspill” cemetery for the rest of the parish.

At the time, Britain was in the midst of the industrial revolution and many poor workers came to London from countryside farms and villages looking for work. When they could find none, they would turn to the workhouses. During this period, the workhouses were built by parishes according to poor-relief legislation. These Poor Laws enabled parishes to take the destitute off the streets while simultaneously profiting from their labour and, perhaps most importantly, reducing the cost to the taxpayer.

Residents of the workhouse would have been employed for oakum picking – laboriously separating the fibres in old ropes for reuse – or linen making, among other things. Dr Rogers wrote of carpets that would be beaten by the “able-bodied” men in the yard from morning to night, creating a dust cloud so thick that opening the windows in the workhouse was impossible, while any sleep for the sick was out of the question due to the constant noise. The workhouse is said to have made £400 (£44,000) a year from carpet beating alone.

“They were really menial, boring, tough jobs,” said Claire Cogar, director of archaeology for Iceni Projects. “You had to earn your keep and often it was a requirement that you stay for two nights so that the master could get a full day’s work out of you. You wouldn’t get let out until 10 or 11 in the morning, by which time you’d have missed all the casual labouring jobs at the market – it’s a vicious cycle of poverty.”

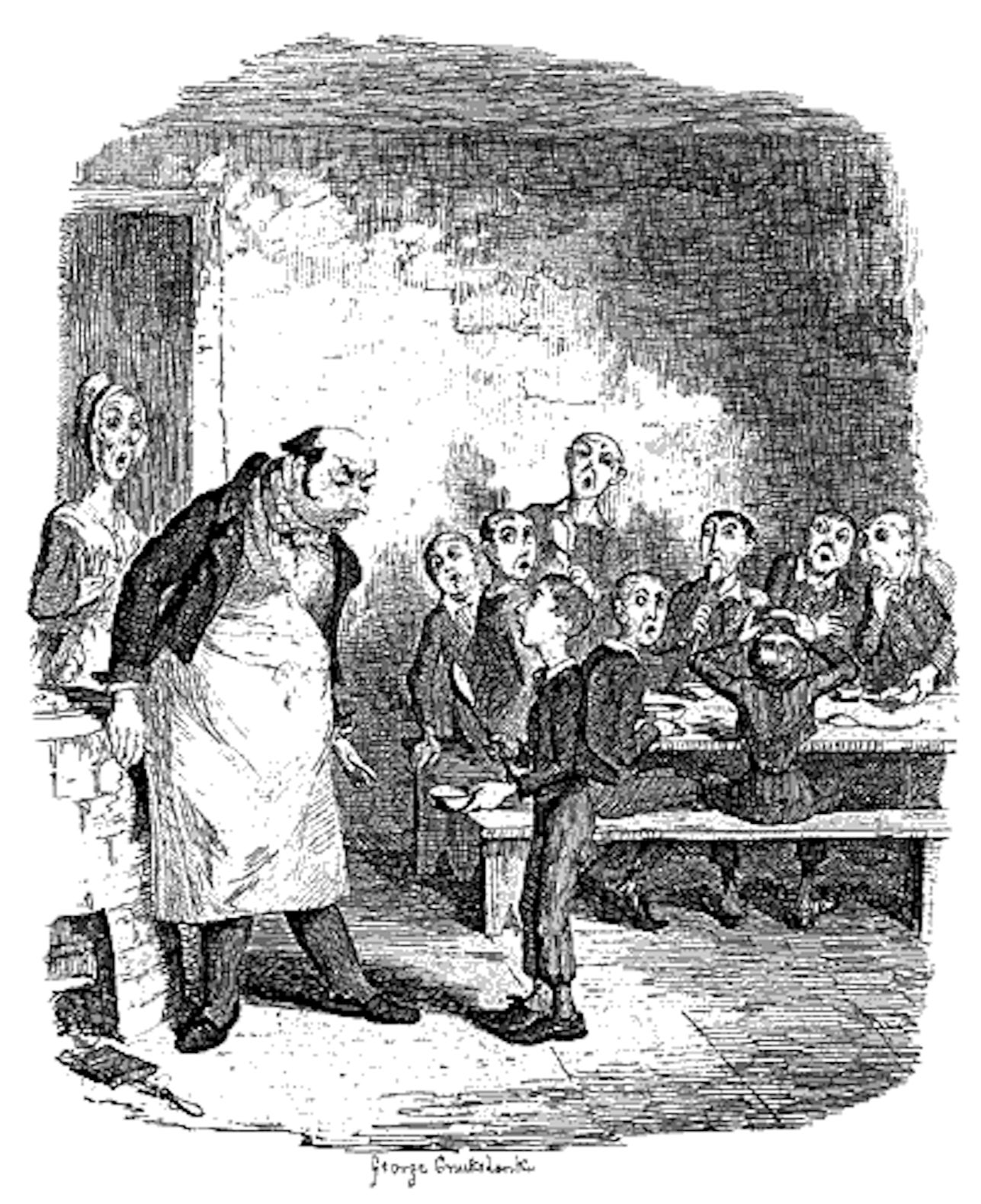

Georgian and Victorian workhouses, according to legislation, were designed to be “uninviting” so that anyone that did not desperately need them wouldn’t use them. Many viewed those that needed the workhouses as the “undeserving poor”, lazy people who didn’t want to work but wanted a roof over their heads and to be fed at the expense of the taxpayer. Residents were fed badly not only because it was cheap, but because they didn’t want the poor to get used to eating well for free.

The conditions of these workhouses are well known through stories and fiction, but the excavation taking place on Cleveland Street is laying bare the reality and revealing Victorian attitudes towards the poor and unveiling some new things, too.

“There are some pretty shocking things here in terms of abject treatment of poor people in this period,” said Guy Hunt a partner at L–P : Archaeology. “Two children buried in the same coffin, for example, that’s the sort of thing that’s arresting even for people that have dug up many burials.”

But perhaps the most surprising discovery is the sheer number of bodies that have evidence of anatomical dissection. With the passing of the Anatomy Act of 1832, it became legal for surgeons to dissect unclaimed bodies within the workhouse system. Before, it was only hanged men and women, which led to the emergence of the “body snatchers”, criminals who would illegally dig up newly buried bodies to sell to surgeons.

With the change in the law, this kind of criminal activity was no longer necessary, and workhouses became perfect places to find unclaimed bodies that nobody would miss, to cut up for research or to practice procedures on. How do the archaeologists know this? Dozens of the skeletons recovered from the northern-most part of the cemetery have had their skulls neatly cut open so surgeons could get at, and examine, the brain in what is known as a craniotomy. Many others show similar signs of deliberate and precise anatomical cutting along limbs and other body parts.

“It’s not unique to find bodies that have had this treatment,” said Hunt. “But what’s interesting about this excavation is the percentages and the quantity. It’s not one or two associated with a particular surgeon it’s almost a whole burial ground filled with people that have had their heads cut open, it’s quite different.”

The tantalising question is whether this was before or after 1832. Was the dissection legal or illegal? Without any evidence for the date of death it is hard to say. And another question is: were these bodies being taken away from the workhouse, dissected and then returned for burial?

Hunt told me that there was evidence that wax-like material was pumped into the veins of some bodies which would have created a more visual effect, clearly highlighting parts of the nervous system when they were being cut open. This suggests that these bodies were used for public autopsy, in a theatre for trainee surgical students to watch and learn about the human body. There is no evidence to suggest there was a mortuary at the workhouse so it’s likely that these bodies were being taken off site, perhaps to the Royal College of Surgeons, and then taken back for burial.

“There’s an industry going on here,” Hunt says. “Either around the anatomy itself or around the creation of medical specimens. These people were rounded up and incarcerated and these are their mortal remains, which were so horrendously treated: many people had strong opinions on not wanting to be chopped up in death and it illustrates the complete lack of rights these people had.”

Under the gazebo I took a closer look at one of the skeletons. It was an adult, which had been fully excavated, its bones packed in tight together, but the archaeologist was lightly brushing at some smaller bones around the chest area. These were the bones of a child, possibly buried with its mother in the same coffin, which has long since decayed.

Much of what we know about the poor in the workhouse in this period comes from fiction. Charles Dickens, who popularised the Victorian workhouse in novels such as Oliver Twist, would have known the Strand Union workhouse. He lived at 22 Cleveland Street, on the same road as the workhouse, twice in his life, once as a child and then again as a teenager.

Historian Dr Ruth Richardson, in her book Dickens and the Workhouse, has even suggested it was this very workhouse which inspired Oliver Twist and later fiction. And on the final page of Oliver Twist, there is reference to the fact that Oliver’s mother, who died in the workhouse giving birth, was an unclaimed body, one of the disappeared: “Within the altar of the old village church there stands a white marble tablet, which bears as yet but one word: ‘AGNES.’ There is no coffin in that tomb.”

“Dickens walked past the workhouse probably every day as a young man,” said Cogar. “The contemporary parallel you could draw is people who are long-term homeless, who sleep rough on the streets all year round, that is the sort of person who would access the workhouse as a last resort. Who could fail to be moved by that?”

Beyond Dickens and other fiction, this important excavation is giving us a factual glimpse of London’s destitute in a period which saw the city and country propelled to one of the most important industrial nations in the world. The story of these people, upon whose backs the City of London was built, is being revealed every day on the Cleveland Street site.

“Many on this site have arthritis,” said Hameed. “We can see this in the polished bones where they’ve rubbed together in labour. Seeing that makes you think about the type of harsh working conditions they were subjected to.”

Erna Johannesdottir, an osteoarchaeologist for L–P : Archaeology told me that while they were only half way through the excavation, and the full analysis was yet to be done, there are deformities such as shortened arms and legs, and there are also clear signs of nutritional deficiencies such as rickets, which can bow the bones and stunt growth. These conditions would have been debilitating to the people that bore them.

Crush injuries are also visible in some of the skeletons, perhaps caused by the machinery in use at the large industrial factories on the site or by the horse-drawn carriages which travelled the streets of London. There are young and old buried here and in some skeletons there is a clear strength to the bones.

“Often these people can be portrayed as dishevelled and gaunt and falling apart,” said Stephen McLeod, a senior archaeologist for Iceni Projects. “But to survive in workhouses for many years you would have to have a certain strength and character about you.

“It’s our job as archaeologists to tell the story of the people that lived in the past, through the material we find. But also to link it to society as a whole.”

An excavation like this can reveal Victorian attitudes towards the poor, which are often divided between the deserving and undeserving. On one side are those that do not work because they can’t, for reasons such as age, ability, or health; these are the deserving poor. On the other side are those that don’t work because they are “lazy”, and these are the undeserving poor. This debate still rages today, and one has to ask how much our ideas have changed since the workhouse?

For example, Dave Beck, a lecturer of Social Policy at the University of Salford, writes for The Conversation that parallels can very much be drawn between Victorian ideas of the poor and footballer Marcus Rashford’s recent campaign for free meals for children over school holidays.

We are not only at the heart of where it all took place but also uncovering the people that have a significant story to tell

Those that oppose free school meals – members of parliament and the public – often suggest it is a matter of agency, that those in poverty “do not help themselves” and are therefore undeserving of free meals. Beck suggests attitudes such as these have not changed much since the days of the workhouse and says these views “demonstrate how low-income communities suffer at the hands of those who ‘punch down’, dispensing judgement or instructing them how to live without having direct experience of poverty”.

Hunt describes what the archaeologists are doing at the workhouse as a “genealogy of the welfare state”. The excavation of the cemetery and yard offers the “middle-part” of that development, between the Poor Laws that began in Tudor times, through to the workhouses and to the benefits system today.

“Thinking about diseases and the furlough scheme, or how the public purse deals with the poorer people in society, it’s clear that we still haven’t come to grips with that. I think it’s interesting that our benefits system is based on the idea that if you give people money they’ll naturally be lazy and they won’t want to work, so our benefits are rigged around the idea of trying to make people work.”

McLeod says it’s a matter of looking at why people had to turn to the workhouses then, and why they may need to turn to foodbanks or to benefits now. He questions whether the creation of the workhouse was really to help the poor or to “sweep them under the rug”.

As the excavation moved to the south of the site the archaeologists found more burials, these were on a traditional Christian east-west alignment and were spaced further apart and more cared for. Hunt believes this may be the overspill burials from the other parish cemeteries, those that weren’t residents of the workhouse but who were too poor to be buried anywhere else.

These were the deserving poor. The north of the site was where many of the bodies that were dissected were found, and the graves were packed in tight, one on top of the other in a herringbone pattern, sometimes people were even buried in the same coffin – these were the undeserving poor; those who had worked hard, suffered and often been cut up in death.

But as Cogar put it: “Those that were dissected and studied contributed to the advancement of modern medicine. So, while they were treated as less than nothing at the time, they have made a huge contribution to society.”

In 1853 the cemetery was closed. As knowledge of sanitation increased – much of which was led by a young Dr Rogers – it became illegal to bury human bodies inside the city, and so many of the burial grounds of London moved further afield, but the workhouse remained open.

Dr Rogers would arrive as the medical officer three years later to begin his long battle for the reform of Poor Law healthcare. Based on his experiences at the workhouse he would become the founder of the Association for the Improvement of London Workhouse Infirmaries which, with support of Dickens and Florence Nightingale, would successfully lobby for the 1867 Metropolitan Poor Bill, providing 20 hospitals across London for workhouse residents, which would have wider reaching benefits for the workhouse system and the poor as a whole.

“Working on this site turns the research, photos and examples we know about into a reality,” said Hameed. “We are not only at the heart of where it all took place but also uncovering the people that have a significant story to tell.”

The workhouse continued to be a place of medical care, later becoming an infirmary and then the Middlesex Annexe and outpatient department as part of the NHS before closing in 2005. The workhouse building itself will return to being residential accommodation, and the UCLHC – University College London Hospitals Charity – which is developing the site, is also constructing a building at the rear of the site, which will house six new MRI scanners, continuing that medical legacy.

The bones of the people that once sought refuge in the Strand Union workhouse will be studied and analysed before being respectfully reburied in consecrated ground. These people will continue to enhance our understanding of public health and society in Georgian and Victorian London.

“It's an incredibly special site,” said Cogar. “And we've only just scratched the surface.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks