Can a people’s tribunal give Uighurs the justice they so desperately need?

China is accused of committing genocide against the Uighurs but no international court is able to bring a case against it. But a people-led initiative, the Uighur tribunal, will start to hear evidence today. Rory Sullivan speaks to camp survivors and lawyers to learn more

Camp survivor Tursinay Ziyawdun wants the world to hear her story and the story of her people. For nine months in 2018, Ziyawdun, a 42-year-old Uighur, was detained in a Chinese internment camp and was subjected to appalling abuse. Her only crime was her ethnicity. By conservative estimates, she is just one of at least a million Uighurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities who have been rounded up and transported to such facilities in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region since 2017, after a government crackdown there.

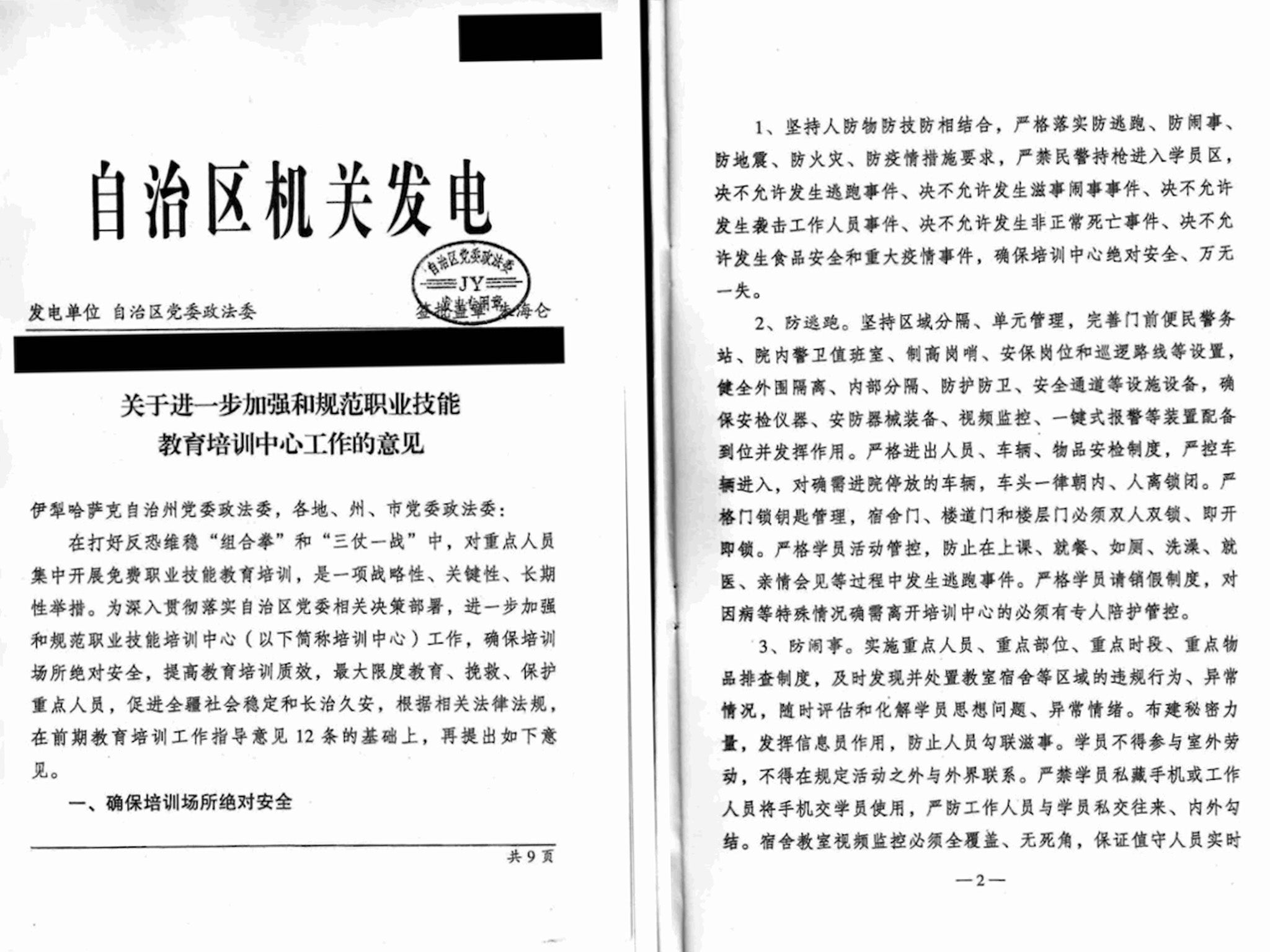

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) insists it is simply fighting terrorism and separatism in the region, and calls the camps “vocational education and training centres”. However, witness testimony, leaked party documents and open-source research make these words ring hollow.

Ziyawdun was born in 1978 into a Uighur family in Kunes county, an area close to Kazakhstan. After marrying a Kazakh, they moved across the border in 2011 and lived there for five years. But unknown to them, a trip to China to renew Ziyawdun’s passport in 2016 coincided with the start of the CCP’s clampdown in Xinjiang.

The first major blow they suffered was the police’s decision to confiscate their passports. Next came her arrest in the street, followed by time spent in a detention centre, where she was compulsorily “re-educated”. "We were forced to denounce our religion and say we didn't believe in God. We also had to memorise the red propaganda slogans,” she recalls.

After about a month, Ziyawdun was released on health grounds. In fact, she was in such a bad state that doctors said she would probably die if she did not receive urgent treatment. She blames the unsanitary conditions and poor-quality food at the camp for her illness.

There was to be no respite though. Discharged from hospital, the then 39-year-old was kept under house arrest, before being taken away on 10 March 2018. Arriving at its gates, she found she barely recognised the place where she had already lived for a month. Extra storeys had been added and barbed wire now coiled above high walls. “When I went the second time, the camp was completely changed. It had been turned into a jail.”

It wasn’t just the camp’s appearance that was different; so was the treatment of those detained. Crammed into a narrow room with 20 people, Ziyawdun and the others had no access to a toilet. Only a bucket, which they were each allowed to use once a day. If they went over their allotted three minutes, they would be punished.

During Ziyawdun’s time in the camp, she was given unknown medication and injections. But the worst came when she was moved to what she describes as the “iron room”. From here, she was led away to be interrogated about her supposed links to Uighurs in the diaspora. After she denied any involvement with overseas organisations, camp officers kicked and beat her, she says.

Camp officials first tortured Ziyawdun with electric shocks to her genitalia. Three men then gang-raped her, an ordeal she would suffer on several more occasions

When women started being taken away at night, Ziyawdun assumed they too were being sent for questioning. Although she heard screams which she likens to “terrible noises from a butcher's”, she did not comprehend what was going on until it happened to her. One evening, she and a 20-year-old woman were ordered to leave their cell and were taken to adjacent rooms. Camp officials first tortured Ziyawdun with electric shocks to her genitalia. Three men then gang-raped her, an ordeal she would suffer on several more occasions. She is convinced that the other woman was also raped next door. “The camp police can do whatever they want to do,” she says.

Speaking about those who experienced similar horrors, Ziyawdun mentions that some women would return to their cells and others “would completely disappear”. The ones that did come back were noticeably changed, with many not speaking at all.

On 25 December 2018, Ziyawdun was released from the camp, a decision she attributes to her husband’s campaigning on her behalf from Kazakhstan. Despite her relief, the couple were not reunited until almost a year later, when Ziyawdun was finally allowed to leave China. Threatened with deportation by the Kazakh authorities once her three-month visa expired and with her health worsening, she moved, via Turkey, to the US, where she underwent a series of operations and where she now lives.

Even if the people’s tribunal finds genocide is being committed, its judgment is not legally binding. But at least it promises to assess the Uighurs’ suffering from the perspective of international law

As well as testimony like Ziyawdun’s from the camps, reports of sterilisation, forced labour and family separation in Xinjiang are rife. China’s widespread destruction of cultural sites such as mosques is also well documented. Around 16,000 mosques – 65 per cent of the region’s total – have been destroyed since 2017, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. On the basis of this evidence, some countries have accused Beijing of committing genocide. After the US, Canada and the Netherlands did so, the UK followed suit in April this year.

Although these declarations signal an important shift in international pressure on China, they are political determinations. In the belief that China should be held accountable in court, Dolkun Isa, the president of the World Uighur Congress (WUC), wanted a case to be brought against the CCP on charges of crimes against humanity and genocide. However, the shortcomings of the international justice system preclude this possibility.

A trial before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is out of the question because China is a member of the UN Security Council and can veto its passage. The International Criminal Court (ICC) is similarly off the table because it has no jurisdiction in Xinjiang, as Beijing is not a signatory of the ICC’s Rome Statute.

Left at this impasse, Isa approached Sir Geoffrey Nice, an eminent human rights barrister, in the summer of 2020, asking him to head up a people’s tribunal examining China’s alleged crimes in the north-west of the country. After considering the WUC’s proposal and the evidence it submitted to him, Nice, who prosecuted Slobodan Milosevic in a UN court of law, agreed to chair the Uighur tribunal.

Under this process, Nice and a panel of eight other citizens will listen to testimony from witnesses (including Ziyawdun) and experts, examine the 2,000 documents in the tribunal’s evidence database, apply international law with the help of legal counsels and then offer a judgment by early 2022 on whether genocide is taking place in Xinjiang. The jury consists of three academics, two lawyers, two doctors, a businessman and an ex-diplomat. The tribunal convenes in London on Friday for its first four-day set of hearings, with a second to follow in mid-September.

Isa, who has lived in forced exile for 27 years, acknowledges it is no panacea. Even if the people’s tribunal finds genocide is being committed, its judgment is not legally-binding. But at least it promises to assess the Uighurs’ suffering from the perspective of international law, he says.

"This is the only option: a people's tribunal to hold China accountable. Because other international institutions, all national courts are impossible,” Isa tells me over video call from his office in Berlin. He hopes the tribunal will raise awareness about the issue and will pile pressure on countries to do more to stop the atrocities. Without collective action in the form of mass sanctions, he fears the destruction of his race’s identity: "The Chinese government cannot kill all Uighurs but assimilation can be realised.”

Even if such help does come, it is too late for his mother, who died in one of the camps. Soon afterwards, Isa learned that his father had passed away too. One year on, he still does not know the cause of his death or where he is buried because of the communication blackout in the region. "I want to hear the voice of my mother, I want to hear the voice of my father. I believe they had something to tell me,” he says.

The history of peoples’ tribunals starts in earnest after the Second World War with an initiative led by the philosophers Bertrand Russell and John-Paul Sartre. This intellectual duo believed that America should be tried for the war it was waging in Vietnam, but understood that a case would never be heard in court. Instead, they set up what they called the International War Crimes Tribunal, now better known as the Russell Tribunal. With a jury of left-leaning intellectuals from 18 different countries, it held two sessions in 1967: the first in Stockholm, the second in Roskilde, Denmark. These venues were chosen after the governments in London and Paris expressed their hostility to the project and said they would not host it, with French president Charles de Gaulle writing that “justice of any sort, in principle as in execution, emanates from the state”.

More than a half century later, the UK has adopted a similar approach in relation to the Uighur tribunal. Approached by the panel to contribute evidence it has on Xinjiang, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) said it could not, as “the government’s long-standing policy is that a determination of genocide or other international human rights crimes is for a competent court, rather than for governments or non–judicial bodies”.

Sartre saw De Gaulle’s – and, by extension, the FCDO’s – dismissal as flawed, saying the process filled a lacuna. He said it “is not a substitute for any institution already in existence: it is, on the contrary, formed out of a void and for a real need”, before adding his belief that its legality comes from “both its absolute powerlessness and its universality”.

The Russell Tribunal, however, is not immune from criticism. The perceived one-sidedness of its jury led many to call it a “kangaroo court” and its unanimous judgment of genocide against the US was also controversial. Similar allegations of perceived bias and a preordained outcome have also been levelled at subsequent tribunals.

Nice, who has served on several peoples’ tribunals himself, thinks the Russell Tribunal was far from perfect. “It seemed to lack the necessary characteristics of objectivity,” he says. Nonetheless, the QC believes Sartre’s justification for peoples’ tribunals – that “they fill a gap” – holds strong.

Speaking over Zoom from his home, Nice tells me that states should not have a monopoly on judging wrongs. With no available alternative, it sometimes becomes necessary for cases to be heard by people, he says. To this end, the 75-year-old waves away anyone who thinks he and his colleagues lack legitimacy. "Of course we have jurisdiction. We're citizens for goodness’ sake.”

On the objectivity of the upcoming Uighur tribunal, he says the panel was deliberately chosen to exclude anyone involved in a China cause. “It's critical that you get a group of dependable jurors who can be dispassionate about the task they've got,” Nice explains.

I like to see it as people taking control of the international law and other laws that are actually meant to be benefiting them and making it theirs

Andrew Byrnes, a law professor at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), also thinks peoples’ tribunals fulfil an important function. Despite sometimes going by different names – including citizens’ tribunals, tribunals of conscience and ethical tribunals – most are grounded, albeit to varying degrees, in law. “I like to see it as people taking control of the international law and other laws that are actually meant to be benefiting them and making it theirs,” he says.

To him, what matters is how the jury engages with the evidence in question. “Legitimacy comes from how you act, what you look at, how you engage with it, whether you hear the other side, what's the power and cogency of your analysis and reasoning and conclusions.”

The former chair of Australia’s Human Rights Centre also draws attention to the wide spectrum of peoples’ tribunals. Gabrielle Simm, his co-editor on the book Peoples’ Tribunals and International Law and a senior lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, says it is hard to generalise about them for this reason. “They're very formal at one end and not much different to a street protest or an alternative to a strike at the other.” It goes without saying that the Uighur tribunal falls in the former category.

The range of issues addressed by them is similarly broad. In recent years, there have been peoples’ tribunals on, among other things, mass murder in Indonesia in 1965, human rights violations in 1980s Iran, water rights in Latin America and organ harvesting in China. One of the most formal and legalistic tribunals was the Tokyo Women’s Tribunal in 2000, brought on behalf of women forced into sexual slavery by Japan from 1932 to 1945. Having their stories told “in a solemn environment where they were listened to” really mattered, notes Byrnes.

Simm agrees that a key role of the panel is to listen and provide dignity to the witnesses. In her opinion, peoples’ tribunals offer victims “more agency, more participation, more ownership, more involvement” than the international courts do. They do not interrupt witnesses and truncate evidence through cross-examinations, she explains. They are also a means of building pressure for a particular cause. Byrnes points out that some of their judgments are considered by international institutions, lending them further weight. This is the case with the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal’s 1984 ruling on the Armenian genocide, he says.

Both Byrnes and Simm are cognisant of the limitations of peoples’ tribunals but believe they are a force for good in the imperfect landscape of international law. “We’ve still got huge numbers of marginalised people who don’t have access to a remedy or even a recognition of the wrong,” Byrnes says.

Qelbinur Sidiq, a teacher from Xinjiang, hopes the wrongs happening in her province will be recognised by the Uighur tribunal. For this reason, she has travelled from her home in the Netherlands to London for the first hearing. As one of the first witnesses to testify before the panel on Friday, she will speak about her experience working in the camps, where she was forced to teach Chinese.

Twenty-eight years into her teaching career, Sidiq was summoned to her local education board and told she had an assignment. She was given no more information. The following day, 1 March 2017, she was driven to an ominous-looking complex with tight security. Recalling her first impressions, the 52-year-old says she was struck by how all the cells’ windows were totally covered. The classroom she was led to was only slightly better, with a little light trickling in. Looking around it, she saw 100 chairs so small she thought they must be for children. Then the camp inmates filed in, 90 of them men and seven of them women.

She welcomed them, as she usually would, with the Arabic greeting as-salamu alaykum. The ill-ease that swept through the room was palpable. Realising she had made a mistake, she quickly turned to the blackboard to compose herself. “When I turned back and I saw the people, the old people, I saw tears coming down through their beards. Their beards became wet,” she tells me, tearing up at the memory. The next four hours were “the longest lesson” of her life, she says.

Over the next six months, numbers at the camp swelled. By mid-April, another 7,000 or 8,000 people had arrived, according to Sidiq. She says they were forced to take unknown medicine and vaccines, and they could only use the toilet a few times per day, details in line with Ziyawdun’s testimony. Similarly, she speaks of disappearances and deaths in the camps.

When I turned back and I saw the people, the old people, I saw tears coming down through their beards. Their beards became wet...

Once her contract expired, Sidiq went back to teaching at her school. She did not have to wait long to be re-assigned: within a month, she was sent to a camp for women in Urumqi’s Tugong district, where she was told she would be teaching “illiterate people”. This turned out to be false. In fact, many of the women were highly educated, forced back from studies abroad after threats were made against their families.

On her first day in this camp, Sidiq saw an 18-year-old Uighur being carried away dead on a stretcher by two Chinese police officers. The young woman had died from blood loss, brought on by a problem with her period, she says. Sidiq tells me rape was endemic in the camp. She heard this from two Chinese police officers and one of her fellow teachers, who all confided in her. Sidiq had already assumed this was happening, after noticing women walking “very abnormally” and moving their bodies “with difficulty” after interrogations.

The faces of the women, devoid of hope, haunted her. “They looked like they knew they would die in the camp,” she says. Being surrounded by such tragedy took a growing toll on Sidiq’s mental and physical health. No longer fit for work, she stopped teaching there after three months and spent time in hospital. "Every day I had pain in my heart. I could not forget what was happening in the camp.”

It was only in February 2018 that she felt well enough to return to her school for what would be her first and last day back. Called into a meeting, she was made to retire three years early by signing the necessary paperwork.

The following year, Sidiq was sterilised at the age of 50 as part of the CCP’s birth control campaign. She pleaded with officials to no avail, showing them the certificate of honour she had received from the government for complying with China’s one-child policy. "When I got to the clinic, there were hundreds of Uighur women waiting in a line. And I waited for four hours and when it was my turn I was sterilised,” she says.

Her daughter, who was living and studying in the Netherlands, had sent her an invitation to her wedding the previous July. Although Sidiq’s application was rejected by the authorities on that occasion, she eventually got permission from Beijing to visit her for one month in October 2019. She believes being an ethnic Uzbek – and not a Uighur – helped.

Sidiq has been in the Netherlands ever since. Early in 2020, she decided to speak out publicly about her experiences. “When I thought about people in the camp, when I thought about their torture, their terrible experiences, I wanted to speak to the outside world.”

Her bravery comes with repercussions. Her husband, a Uighur, is still in China and was coerced last year into denouncing his wife on video, saying she never taught in the camps and had not been sterilised. During their last conversation on 24 December 2020, he apologised to her for not being able to protect her. He added that it had taken him four hours to film the short clip, as the police officer filming it repeatedly told him that people would know he was “lying” because he sounded unconvincing.

Police also routinely intimidate and harangue her siblings. The day before our conversation, her siblings contacted her to curse her and tell her to stop speaking out. Although she knows the police made them do it, it is still hard to take, she says. Especially her sister’s words: “Do you want us all to die?"

Despite such pressures, Sidiq is resolute in her determination to spread her story more widely. "My family has been destroyed by the Chinese government. But I won't stop speaking the truth for the Uighur people about the crimes of China. China cannot stop me."

My family has been destroyed by the Chinese government. But I won’t stop speaking the truth for the Uighur people about the crimes of China. China cannot stop me

Adrian Zenz, senior fellow in China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, will likewise not stop talking. He is one of the world’s leading academic experts on the repression in Xinjiang, and has vetted the authenticity of two of the biggest leaks from the region: the China Cables and the Karakax List.

The first of these, originally published in November 2019 by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, refers to two caches of CCP documents showing top-level government policy. It spells out that the party – in the words of leader Xi Jinping – would give “absolutely no mercy” to the Uighurs and other ethnic minorities. It also reveals guidance for the camps, including a minimum detention time of one year. The Karakax list, a 137-page pdf file, is on a smaller scale, as it pertains to one county in Xinjiang.

However, the data it contains on more than 300 imprisoned individuals is crucial to understanding China’s modus operandi. Among the reasons listed for internment, the most common ones are “having a passport” and having “too many children”, followed by others including praying at home and keeping in touch with overseas relatives.

The German-born academic has published multiple papers on the atrocities committed against the Uighurs, including a recent one on forced labour. However, he will predominantly speak about his research on birth control when he appears before the Uighur tribunal this week.

"A very strong case can be made for a slow genocide over time,” he tells from over the phone from Minnesota. Influential people in the Uighur community have been disproportionately targeted in a bid to destroy the group, something which could take place over the course of a few decades, he explains. Internal leaked documents show that between 30 and 50 per cent of those detained are heads of households. Their eldest children have also been singled out, with the same being true for “key intellectuals, religious figures, artists, influential people”, he says.

Zenz thinks China’s internment campaign acts as “a backbone of the atrocity” because it eliminates all forms of resistance, allowing the state to break down the Uighurs and implement policies such as birth control at will.

Genocide is not only committed by mass killing, Zenz says. This notion is explicitly laid out in Article 6 of the Rome Statute, the definition of genocide which the Uighur Tribunal will use to form its judgment. Under this article, the threshold for such a crime is met when any of the following acts is intentionally committed to destroy a group, in whole or in part:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Much of Zenz’s research has relied on data, which, until recently, has been publicly available. But given mounting international criticism, Beijing has started to withhold snapshots such as those provided in the annual Xinjiang Statistical Yearbook, whose 2020 edition contained glaring omissions. This comes on top of a severe clampdown on communication between Xinjiang and the outside world.

“We have an information blackout. Since 2020, the information situation has become very problematic. Now in addition, China is withholding population data. That’s extremely concerning,” Zenz says.

In the interests of transparency, several databases dedicated to the atrocities in Xinjiang have been launched in the past four years. One is the Xinjiang Victims Database, also known by its domain name shahit. Founded by Gene A Bunin, a Russian-American researcher who lived in Xinjiang, it catalogues information on people who have been detained in camps or imprisoned, as well as those whose families have been separated. Data from leaked documents and open sources like social media are ingested into the database by a small team of part-time staff and a larger team of volunteers.

Hanna Burdof, a Uighur-speaking PhD student who works at shahit.biz in her spare time, tells me about its mission. "The goal of shahit is to make everything public – as much as possible. Because we believe that the Chinese government doesn't like this and the only way to put pressure on them is to reveal what they are responsible for,” she says.

According to its data on more than 15,000 victims, the ratio of people sent to prison in Xinjiang as opposed to camps is one to two. Yalqun Rozi, a prominent Uighur intellectual, is in this smaller – but still extremely sizeable – group.

Speaking from his home on the east coast of America, Kamalturk Yalqun recalls his family’s last conversation with his father. It was in October 2016 and “his tone was a little nervous”, his son recalls. Several months before, a fun autumn was on the horizon. Yalqun’s mother had joined him and his sister, who were both studying in the US, and his father was due to fly over for a two-month family road trip.

Unfortunately, trouble had flared at the Xinjiang Education Press, where Rozi had worked as an editor until his recent retirement. The problem centred on a series of Uighur-language textbooks that the publisher had produced in the early 2000s, in a form approved by Chinese censors. Although the family knew Rozi had been called in for meetings at the press, they were not unduly worried, as there had been murmurs about these books in 2012 and they had subsequently been taken out of circulation. His children and wife were still not overly concerned when he told them he was not allowed to leave his home city of Urumqi and would have to cancel his flight. But then he went missing and the family frantically called around for any information about his whereabouts.

The next they heard was when the Xinjiang Education Press released a statement in December, saying that Rozi and a colleague were suspected of the “crime of separatism”. Thirteen months later, the family learned that Rozi had been given a 15-year prison sentence for “subversion”. Yalqun says Chen Quanguo, the architect of the internment camps, first targeted intellectuals like his father after he became Xinjiang’s CCP committee secretary in August 2016.

The now-exiled trio’s pain and stress was immense, with Yalqun dropping plans to become a doctor and scrambling to find a job so he could be the family’s breadwinner. The news coming from their homeland made the situation all the more bleak. “By the beginning of 2019, almost everyone we knew was already in the camps or the prisons. We heard ‘this person was taken away’ or ‘that person was taken away’ continuously for two years,” Yalqun tells me.

With no potential targets left among their friends in Xinjiang, he and his family chose to speak out publicly. Two years later, Yalqun speaks about the demolition of his people’s “religion, language, culture, history and literature” in a matter of years. China has killed the Uighurs “psychologically”, he believes. Although he will not be giving evidence to the Uyghur tribunal, Yalqun plans to follow it closely.

Beijing does not remain silent in the face of such criticism. Denying all charges made against it, the CCP has taken an aggressive stance towards its detractors. Shahit keeps having to pay “more and more” for security to prevent hacking attempts, while individuals like Nice and Zenz have been hit with sanctions. Given his work, this came as no surprise to Zenz. Nice, on the other hand, was left perplexed. “Our tribunal is a jury; we haven't reached a view yet,” he says, adding that the Uighur tribunal starts without assumption or presumption of any kind.

As part of its playbook, China typically tells other states not to interfere in “domestic affairs” and writes off allegations of human rights abuses as attempts at bullying. The Chinese embassy in the UK typified this approach by saying that the British parliament’s motion on genocide in Xinjiang was “the most preposterous lie of the century”.

Other Chinese proclamations dismiss individual charges, like a recent tweet rubbishing reports of sterilisation. In a logic-defying post, the Chinese embassy in the US said that the reduced birth-rate among Uighurs was down to the CCP’s campaign against extremism, which had emancipated women in Xinjiang and meant they were “no longer baby-making machines”.

The Chinese embassy in London did not respond to The Independent’s request for comment on the charges set out in this article. China also did not reply to the Uighur tribunal’s letter of invitation, asking it to participate in the forthcoming proceedings. Nonetheless, Beijing’s position on these issues is clear, with state broadcaster CGTN saying last week that the tribunal’s investigations constitute an attempt to “attack Xinjiang and smear China”.

Although I look like I’m alive, I’m already dead. The Chinese government took everything from me. They took over my body, they took over my mind. Everything. I have nothing left

For all China’s threats against those speaking out about the atrocities in Xinjiang, many will not be cowed. The academic Zenz is among them. “Knowing that the largest country in the world doesn’t like you is not an easy thing to live with. It does cost emotional energy. But at the same time, it increases one’s determination. Much of what the Chinese government does and says confirms the importance of this work,” he says.

Attacks against camp survivors such as Ziyawdun are also common. Officials in Xinjiang held a press conference in which they ridiculed witness testimony, while holding up pictures of Ziyawdun and others. In a similar vein, the Chinese state media outlet The Global Times published an article in February calling her “nothing more than a liar”. This does not bother Ziyawdun, who expects such whitewashing.

"I'm not scared of the Chinese government. I am not scared of them at all. Although I look like I'm alive, I'm already dead. The Chinese government took everything from me. They took over my body, they took over my mind. Everything. I have nothing left,” she says.

She sees her role as giving voice to the voiceless and hopes the Uighur tribunal manages to increase publicity about the crimes in Xinjiang. “I want the world to know exactly what’s going on and people to contribute to stopping this genocide - that’s my purpose,” she explains.

“I hope the world doesn’t look away from what’s happening to my people. So many people have died. But at least make the living know what freedom is.”

The first set of Uighur tribunal hearings runs from 4 to 7 June, and will be available to watch on YouTube

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments