‘Tears of a clown’: The complicated life and genius of Tony Hancock

He brought great joy to many across the world but always struggled with himself. Then in 1968 he took his own life at just 44. James Rampton examines the real man behind the persona

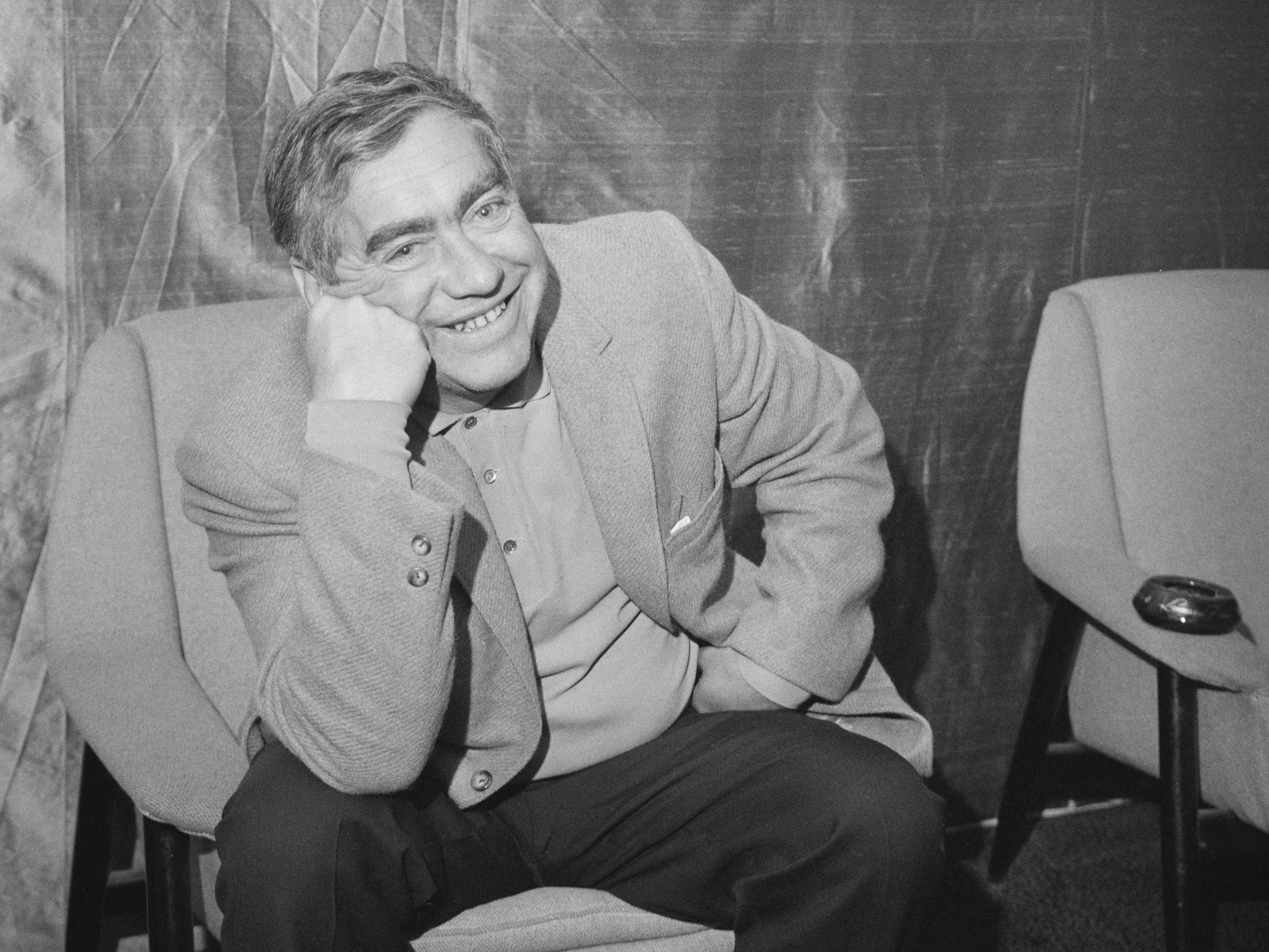

Fifty-five years after the death of Tony Hancock, the great-niece of the comedian never ceases to be amazed by the astounding and enduring influence of her great-uncle’s work.

To illustrate the point, Lucy Hancock tells a story about the far-reaching and completely unexpected impact of one of his most celebrated TV episodes, “The Blood Donor”, in which Hancock grumbles to a doctor about having to give a pint of blood and famously moans: “That’s very nearly an armful!”

“Something my sister and I have always battled with is asthma,” Lucy tells me. “A few years ago, she was having an asthma attack, and I took her to the local hospital. We sat in the waiting room for about an hour before we finally got to see the doctor.

“He looked at her surname and asked, ‘Hancock? Any relation to Tony?’ And we said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Why didn’t you tell us sooner? We would have got you in earlier. We’re constantly referencing ‘The Blood Donor’ in hospitals. We love it!’ I thought, ‘We could have utilised that and got VIP service!’”

This anecdote underscores the abiding love people feel for Hancock. Even today audiences revel in peerless moments such as the comedian’s impassioned speech to his fellow jury members in 1959’s “Twelve Angry Men”: “Does Magna Carta mean nothing to you? Did she die in vain?”

As the 55th anniversary of his untimely death approaches, why are audiences still so enamoured of Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock? This question is addressed in Hancock – Very Nearly an Armful, a comprehensive new documentary that goes out on Gold at 8pm this Saturday.

People are drawn to the universality of the persona depicted in Hancock’s Half Hour, which during its heyday in the late 1950s and early 1960s attracted audiences in excess of 11 million (a figure that nowadays comedians would sell their granny for). “The Lad Himself” from 23 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam was someone we could all relate to.

Lucy, who has also recently published a book on her great uncle entitled Tony Hancock: Inside His Life in Words and Pictures, says, “The show is about the average man’s struggle with day-to-day life and that will always be applicable to people.”

The comic actress Diane Morgan confesses: “Eighty per cent of what I’ve learnt is all Hancock. I shouldn’t really admit that, should I? He stands the test of time because he’s human and is pompous and has dignity, and we can all see ourselves in him. We all want to come across as better people. He shows us our frailties.”

It is true that viewers warm to Hancock’s very evident flaws; however hard he tries, he always seems doomed to fail. His writers, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, built on the comic’s own character to create a classic, pompous persona whose ambition always outstrips his ability.

The playwright and novelist JB Priestley, no less, spotted this trait in one of Hancock’s early live performances: “Here is a man who comes on stage with swagger and bluster and tries to entertain us, but ends up a dishevelled wreck.”

In writing character-driven, 30-minute stories with no interruptions or silly voices, Galton and Simpson invented the modern sitcom for Hancock

The actor Neil Pearson chips in that we can all identify with Hancock’s TV character: “A highly ambitious but vastly underachieving ordinary guy shaking his fist at a universe that really doesn’t care.” His screen persona is, “someone everyone recognises and everyone sympathises with, while laughing like drains.”

Much of the humour in Hancock’s Half Hour, which ran on the radio and then TV from 1954 to 1961, resides in the gulf between his aspirations and reality.

At one point in 1961’s “The Blood Donor”, for instance, Hancock momentarily stops complaining about having to give very nearly an armful of blood and starts proudly puffing himself up when he discovers that he is AB negative, a very rare type. This revelation very much appeals to the snob in Hancock.

“That’s the perfect epitome of the person with ambitions and aspirations above their abilities and above their station, if you like,” says Nigel Planer. “He’s got grander ideas, and that pomposity makes him funny.”

In writing character-driven, 30-minute stories with no interruptions or silly voices, Galton and Simpson invented the modern sitcom for Hancock. And they kept breaking new ground. For instance, one of the best-loved episodes, “The Bedsitter” (1961), was a bold one-hander, relying entirely on Hancock’s brilliance at captivating an audience.

Hancock’s Half Hour also played to his great strength: his supremely expressive face. Nanette Newman, who co-starred with Hancock in his movie “The Rebel” (1961), praises, “The way Tony could convey things by being silent, just watching the wheels go round. Really incredible.”

There is a memorable moment, for example, in “The Reunion Party” (1960), where Hancock’s face undergoes all manner of torment as he desperately tries to remember the name of an old army pal.

His facial expressions also highlighted his capacity to combine the funny with the sad. The comedian Lucy Porter says, “Tony Hancock had the kind of thing that Tommy Cooper had where you laugh because they look so defeated before they’ve even said anything.

“They’re shambolic and destroyed, but they’re trying to hold it all together. There is something very appealing about that. We know he’s struggling, but he’s trying to put a brave face on it.”

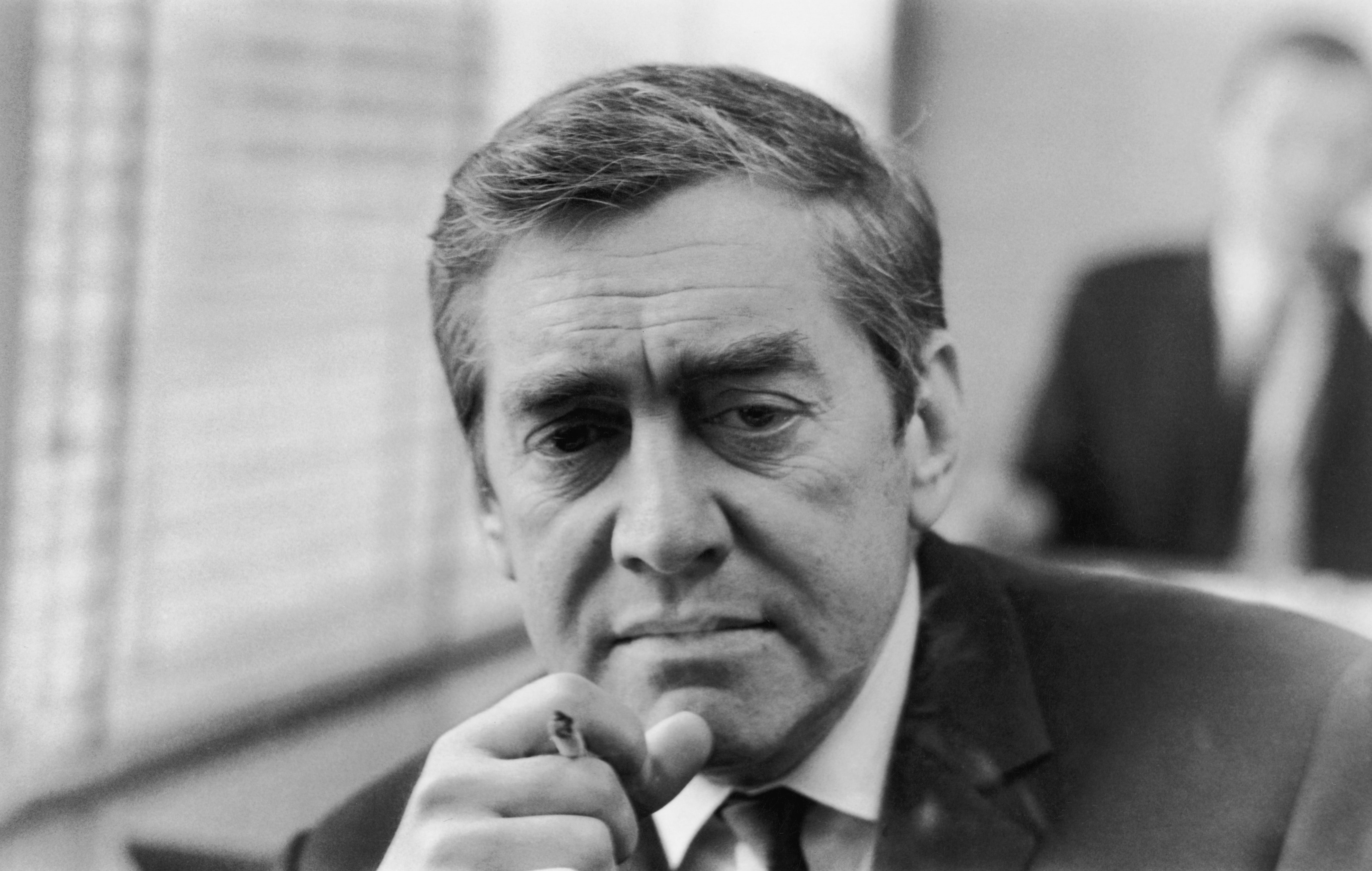

But at the peak of his popularity, the seeds of Hancock’s decline were already being sown. The problem was, he desperately wanted to be taken more seriously.

In 1960, he agreed to be interviewed by John Freeman on the very earnest cultural programme, Face to Face, but it did not go well. “He wanted to be taken seriously,” says Pearson, “and therefore he wanted serious people to pay him attention and he wanted to be asked serious questions … until he was asked serious questions.”

His frustration at his lack of education and eagerness to better himself started to cause difficulties for Hancock. The comedian Jack Dee, who presents Hancock – Very Nearly an Armful, says, “Most comedians get into comedy because they have a very clear sense of tragedy – they’re two sides of the same coin, after all. In Hancock, I perceive an intellectual curiosity that never came to fruition through being able to go to university and study.”

Hancock also began to dissect his own comedy, often a hazardous and counterproductive process. The stand-up Eddie Izzard says, “When he started analysing where the comedy was coming from, that was a problem. He was thinking too much about it.”

The comic was keen to develop new strings to his bow. Newman recalls: “He talked about how he was sick to death of playing the same character. He longed to break out of that and give himself something different to do.”

This led to Hancock making the biggest error of his career. In 1960, he split from his long-term screen partner Sid James and the following year from his stellar writers Galton and Simpson. But, unable to escape the popularity and history of his 23 Railway Cuttings persona, he never hit the same comedy heights again.

Pearson describes the break with Galton and Simpson as, “Madness. Galton and Simpson were and remain the best. Why would you want to work with someone who wasn’t?”

Drinking heavily at this point, Hancock went to work for ITV. However, his alcoholism had started to impinge on his work and his performances suffered. His fellow cast members sent him a letter begging him to rehearse more.

Things only got worse for Hancock, though. Having turned down three Galton and Simpson film scripts, in 1963 he starred in The Punch and Judy Man, a poorly received movie that he co-wrote. Pearson calls it, “Downbeat, dreary, a failure.”

After his 1967 series for ITV, Hancock’s, bombed, in a last throw of the dice, he attempted to resurrect his career by reprising his East Cheam character in Australia. Sadly, the series was never completed because. on 25 June 1968, Hancock took his own life. He was just 44 years old. He left a heart-rending note saying: “There was nothing left to do. Things seemed to go wrong too many times.”

The comedian Spike Milligan later said that he saw Hancock’s demise coming. “He was a very difficult man to get on with. He used to drink excessively. You felt sorry for him. He ended up on his own. I thought, ‘he’s got rid of everybody else, he’s going to get rid of himself’, and he did.”

Throughout his life, Hancock was a victim of a perfectionism which very much fought against his happiness. Lucy, who two and a half years ago in a family storage unit discovered the treasure trove of previously unseen Hancock material that formed the basis of her book and the documentary, says, “The phrase ‘tears of a clown’ sums it up very well.

“There’s no comedy without tragedy. Even when Tony was wildly successful on stage, he would come back and pick apart where he could have done more to make people laugh. He was his own worst critic. He put himself on this impossible pedestal. He was constantly battling with himself.”

Porter emphasises that Hancock’s relentless search for perfection was the root of his downfall. ”His life seems to have been in some ways trying to prove to himself that he had something in him that was special and that he could do it without his co-stars and his writers.

“But ultimately he could never prove to himself that he really had the thing that he craved, which was genius.” The irony is, of course, that now Hancock is universally hailed as just that: a genius.

Hancock was also unfortunate to have lived at a time when it was just not the done thing to talk about your feelings. Lucy laments that he was unable to speak publicly about his mental anguish

It is the curse of clowns to be able to make everyone happy but themselves. “I’ve worked with one or two comedians,” says Newman. “They are so successful at making people incredibly happy by being funny. That’s what people love them for. But in their private lives, they have great difficulty being happy themselves. I rather felt that was true about Tony.”

A large part of Hancock’s problem was that he gave so much of himself to his comedy. The comedian Marcus Brigstocke says: “If you work like he did and put as much of yourself into work as he did, it doesn’t leave an awful lot for whatever else there is, for happy relationships and contentment on your own.”

Hancock was also unfortunate to have lived at a time when it was just not the done thing to talk about your feelings. Lucy laments that he was unable to speak publicly about his mental anguish. “He was a very troubled soul. It was just heartbreaking to read certain things about him, but it was taboo to talk about them in those days.

“It was a really tough time, especially for men, to talk about mental health and depression and anxiety and alcoholism, whereas now it’s accepted, and people are still loved and supported. There’s nothing worse than bottling up your problems. But Tony was at the height of his fame. He wanted to show that he was strong and that he was at the top of his game. But he was a very vulnerable person internally. Depression is a terrible, terrible thing. Combine that with struggles with alcohol and it’s a recipe for disaster.”

Despite his tragically early death, Hancock still exerts an immense influence on the comedians who have come after him. As Dee puts it: “Tony was an incredible talent. While Magna Carta may have died in vain, Tony left behind an extraordinary legacy, changing the landscape of comedy and continuing to influence performers we see today.”

Hancock’s self-deluded persona can be seen in such marvellous comic characters as Basil Fawlty, David Brent, Alan Partridge and Del Boy. “They’re not winners in life,” says Porter. “They can see where they need to be, but they just can’t get there. That’s always going to be funny in the most tragic way.”

What does Lucy hope that audiences will take away from Hancock – Very Nearly an Armful, then? “I hope people realise he wasn’t just an alcoholic who got his lines wrong towards the end. There’s much more to him. He was a vulnerable, complex individual and a lot of people will be able to connect with that. His shows are about striving for socially unattainable standards and battling your inner demons whilst also still making the world really laugh.

“Even though he took his own life at 44, he accomplished so much in such a short time. He was so worried about making his mark on the world and having people love him. If only he knew the legacy he’s left behind, he’d be very proud of himself.”

His great-niece carries on, “I hope somewhere he is looking down and seeing how much his work still affects people. 70 years after the start of his career, he is still being talked about. That’s wonderful. He was a revolutionary artist and to share his surname is a great honour.”

We’ll leave the last words to Edward Joffe, the comic’s last producer. He discovered Hancock’s body and afterwards wrote a moving letter to his mother from Australia: “I do so wish I could be with you to offer consolation personally and to talk about a man whose gifts blessed so many with laughter and now, alas, with tears.

“The entire world must join you in your sorrow for you have not only lost a son, but a man whose genius to make people laugh will be remembered for as long as mankind can laugh.”

‘Hancock – Very Nearly an Armful’ goes out on Gold at 8pm on Saturday 14 January. This will be followed by newly colourised versions of ‘Twelve Angry Men’ and ‘The Blood Donor’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments