The real story of Stonehouse – the MP who faked his death

John Stonehouse’s whole life had a ‘stranger-than-fiction’ tint to it. James Rampton speaks to the creators of ITV’s new drama to find out more

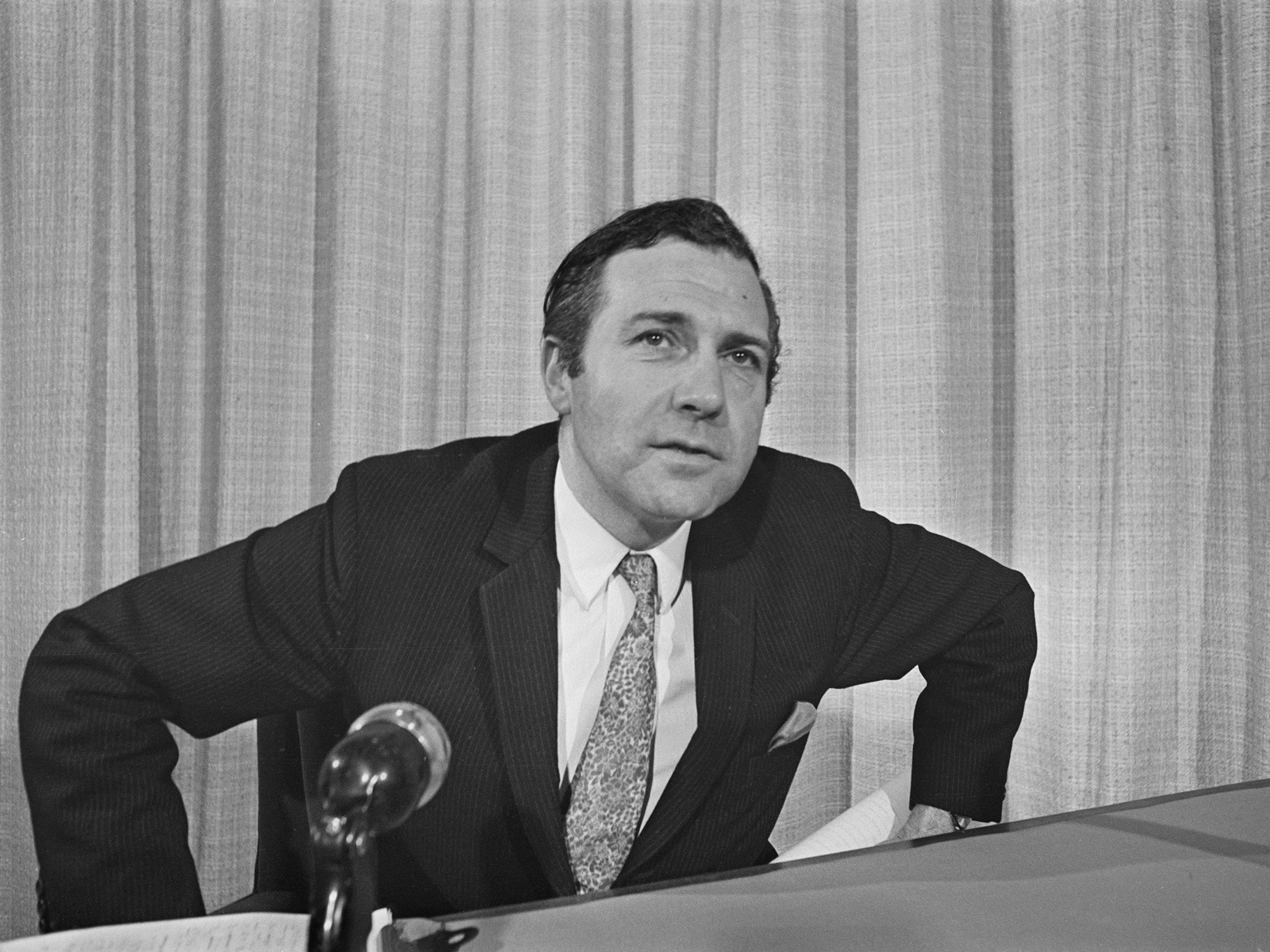

Matthew Macfadyen plays the title character in Stonehouse, a new ITV drama about the almost-unbelievable story of Labour MP John Stonehouse faking his own death in 1974 and nearly getting away with it.

“I was telling my 16-year-old the Stonehouse story this morning, and he said, ‘What? Really? That’s not true, is it?’” The actor says.

Macfadyen’s son is not alone in finding the tale of the disgraced Stonehouse quite literally incredible. Nearly half a century later, people still struggle to believe these events actually took place.

This “fact-is-stranger-than-fiction” yarn is so outlandish that two years later it became perhaps the first ever example of an unimaginable political story inspiring a sitcom – The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin. But there is a distinct “you couldn’t make it up” quality to Stonehouse’s entire life story.

Elected as Labour MP for Wednesbury in Staffordshire in a by-election in 1957, the charismatic London School of Economics graduate soon became a rising star of the party. But his career took its first wrong turn in 1962 when, as a junior aviation minister, Stonehouse began spying for Czechoslovakia.

Stonehouse was apparently blackmailed into becoming an agent after being secretly filmed in a compromising position with his Czechoslovak interpreter in a Prague hotel. His espionage escapade only came to light in December 2010 when it was disclosed that, in 1980, then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had suppressed the discovery that Stonehouse had been a Czechoslovak spy since 1962 as there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him.

The MP revelled in the glamour of being a secret agent. To reinforce the point, he started making a lot of rash investments. He bought a grandiose country pile and a “midlife-crisis” convertible sports car with the hefty clandestine payments that Czechoslovakia was handing him.

When the then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson (played in the drama by Kevin McNally) suspected that Stonehouse had become an agent for Czechoslovakia, the MP managed to convince his boss that he was merely interested in Bohemian glass-blowing and Czechoslovak animation. Impressing Wilson with his suavity, Stonehouse was made Minister of Posts and Telecommunications in 1969.

But he was a lightweight fantasist who had started to believe his own hype. When his wife Barbara (played by Macfadyen’s real-life wife, Keeley Hawes) began to question his investments in the drama, he patronisingly dismissed her qualms: “Darling, I really do think these sorts of things are best left to me. After all, which one of us is a graduate of the LSE? I assume you’ve forgotten.”

And yet he was in great financial peril. His Czechoslovak handler despaired of Stonehouse’s incompetence as a secret agent. As the British minister disclosed to him some insignificant information about stamps, the handler sneered at Stonehouse: “If I wanted to know about the postal service – which I really don’t – I’d join the stamp club … You’re the worst spy I’ve ever come across.”

When the Czechoslovak handler then threatened to cancel Stonehouse’s secret payments, the MP protested: “But I’ve got three children at expensive public schools.”

“Of course. Like all good socialists.”

Stonehouse neatly folded his powder blue suit on Miami Beach, walked into the sea and disappeared into thin air. Believing him drowned, the authorities declared him dead

To exacerbate his deceitfulness, Stonehouse’s image as a loving family man was another sham, as in 1969 he had commenced an extramarital affair with his secretary Sheila Buckley (Emer Heatley), who was more than two decades his junior. When Czechoslovakia finally stopped paying Stonehouse, he was confronted with fraud charges, impending bankruptcy and the implosion of his family.

His world on the brink of collapse, Stonehouse hatched an outrageous plot. Apparently inspired by the film version of The Day of the Jackal, he obtained a passport in the name of Joseph Markham, a dead constituent, and planned to fake his own death before embarking on a new life under a false identity in Australia with Sheila.

Callously telling his wife and three children that he was going to the US on a business trip and would see them in a few days, he left them behind knowing that he was unlikely ever to lay eyes on them again.

On 20 November 1974, Stonehouse neatly folded his powder blue suit on Miami Beach, walked into the sea and disappeared into thin air. Believing him drowned or eaten by sharks, the authorities declared him dead and obituaries were printed.

But the improbable nature of this story does not end there. Lord Lucan had vanished a fortnight before Stonehouse, after his children’s nanny, Sandra Rivett, had been murdered. Australian police officers arrested Stonehouse in Melbourne on 24 December 1974 in the belief that he was Lucan.

They only found out that he was not the missing peer when they ordered the MP to take down his trousers to see if he had Lucan’s trademark 6-inch scar on the inside of his right thigh. Having failed to be granted asylum in Sweden or Mauritius, Stonehouse was extradited to the UK six months after his arrest. He was released on bail from Brixton Prison in August 1975.

He was allowed to carry on as a Labour MP because the party at the time had a wafer-thin majority in the House of Commons. Whoever said politics was cynical or devoid of morality?

Facing 21 charges of fraud, theft, forgery, conspiracy to defraud, causing a false police investigation and wasting police time, Stonehouse represented himself in court. After a 68-day trial, on 6 August 1976 he was convicted and sentenced to seven years for fraud.

After three heart attacks in jail, he was released after three years. He went on to marry Sheila in 1981, write four thrillers and made many TV appearances. Stonehouse died in 1988 after collapsing during the filming of Central Weekend in Birmingham. The subject of the programme? Missing persons.

John Preston, who wrote Stonehouse as well as A Very English Scandal about Jeremy Thorpe, and Fall about Robert Maxwell, details why, 48 years after it happened, the MP’s disappearance remains so compelling. “I had done A Very English Scandal, so I thought, ‘Oh, God, people will think my whole life has just been a ceaseless trawl through 1970’s reprobates!’ But I’ve always been fascinated by the story of Stonehouse because it just seems unbelievably weird.”

At a time when politicians are prone to doing extraordinarily bizarre things, Stonehouse is also very tropical. Jon S Baird, the director of the drama, which begins on ITV at 9pm on 2 January, says: “It’s a great thing to make this production now. Because if you’d made this 10 years ago, I don’t think it really would have felt so relevant.

“But now, post-Trump, post-Brexit and post-Johnson, we’ve got these ‘personality’ politicians. It’s how people are viewing politics.” Stonehouse, he says, still chimes with us because “he was an enormous ego.”

It is also intriguing to explore what possessed Stonehouse to think he could get away with it. Vanity clearly played an immense part. Baird reflects, “He thought he was so much cleverer than everybody else that nobody would notice. There’s a huge element of narcissism in that.”

Macfadyen chips in that this characteristic is present in many MPs. “You spot that vanity in politicians because it’s the nature of the job. They’re insulated and in a powerful position. Then they have an inability to change tack or jump off that path.”

Stonehouse’s narcissism was also mirrored in his sadly mistaken belief that he was a terrific spy. “He always thought he could have been a secret agent,” Macfadyen continues. “In his later years, he liked listening to movie soundtracks, like Bond and The Day of the Jackal. In his own mind, there was a whiff of the secret agent about him.”

That self-deception was evident in Stonehouse’s self-aggrandizing novels as well. According to Preston, “They’re very sub-Jeffrey Archer. But what’s quite interesting is that there is a weird subtext there. You feel that Stonehouse sees himself in this rather dashing light. There’s a certain sense of wish fulfilment there – ‘this is me as the secret agent.’ You feel the spirit of Stonehouse shines through the main character.”

Of course, in reality, Stonehouse was a hopeless secret agent. “He really was a very bad spy,” Preston laughs. “The Czechoslovaks were recruiting quite a lot of MPs and trade union leaders at the time, none of whom delivered anything of any use at all. But even by those standards, Stonehouse was unusual.

“I think he had this peculiar idea that any information that he imparted was, by definition, extremely important. He liked the Czechoslovak money – he did have expensive tastes. But then obviously, he got into more and more financial difficulties.”

Stonehouse, who is thought to have had many affairs before Sheila, Baird says. “If they weren’t politicians, a lot of those people probably wouldn’t be as successful in their affairs – I’m trying to put this as politely as I can! Let’s just say they are punching above their weight. Power is an incredible aphrodisiac.”

The other trait that enabled Stonehouse to pull off this outrageous fraud was his manipulative character. “He was an incredibly charming guy,” says Baird. “When he walked into a room, everybody turned their heads. He was a very good-looking guy, and he had this charisma about him. You could see how Stonehouse could manipulate a situation and get people onside.”

Another reason why Stonehouse was drawn towards this preposterous scheme was the fact that he was an incorrigible showman who believed normal rules didn’t apply to him

Stonehouse was blinded by self-delusion, too. “Why did he do this completely mad thing?” wonders Preston. “Why wasn’t a little voice of common sense in his head saying, ‘No, no, no, whoa, whoa, whoa, you can’t do that!’”

Perhaps Stonehouse’s fantasising tipped over into something more serious. “I think Stonehouse initially did a lot of good in Parliament,” Baird observes. “He probably went into it for the right reasons, but there was just something about his personality that was ripe for corrupting. People may argue that there’s mental illness involved. It’s quite a drastic thing to do to your family. That’s a very cynical thing to do. It takes an incredibly selfish human being to be able to do that.”

Another reason why Stonehouse was drawn towards this preposterous scheme was the fact that he was an incorrigible showman who believed normal rules didn’t apply to him. That is another parallel with many contemporary politicians. “If you’ve ever set foot in the House of Commons, you’ll see it’s theatre, it’s Shakespeare,” Baird says.

“There’s so much drama there, especially now that it’s televised. Some of the most egotistical narcissists are some of the best performers. Although I think he is a terrible politician, Boris Johnson is a fabulous performer – that’s why he won an election. Politics attracts those kinds of people. If you look at Johnson’s school reports, he was always going to be in Parliament.”

Baird ponders what audiences might take away from the saga of Stonehouse. “I hope it keeps people questioning who is representing them and the things that they are capable of doing.”

But, “Sheila and Barbara are still living, so we didn’t want to do a hatchet job on this guy because there are still people around who love him.

“Stonehouse was still a human being, but he did something incredibly bad. Sitting there in front of your children and saying to them you’re off for a couple of days while knowing that you may never see them again – that takes a cruel, cruel heart.”

Before we part, I ask Baird one last question. If Stonehouse had been around today, would he have emulated another MP by fleeing to Australia and trying to rehabilitate his reputation and boost his finances by appearing on ITV’s I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here!?

“Oh my God, he would have been at the front of the queue knocking on ITV’s door. He would have been phoning up Ant and Dec personally and saying, “Sign me up right now!” 100 per cent, he would have been doing that. Just imagine the nonsense he would have talked in the jungle as well. It would have been just brilliant.”

Stonehouse begins on ITV at 9pm on 2 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments