Was Oppenheimer really the ‘father’ of the atomic bomb?

As Christopher Nolan’s epic is released, other great men and women surely deserve ‘parenthood’ of this moment in history, says Guy Walters

It is always too easy to fall for the great man – or great woman – theory of history. Massive world-changing events, discoveries, inventions, you name it, all can readily be ascribed to a single individual, thereby making historical analysis a complete breeze. The Second World War? Blame Hitler. The theory of gravity? Isaac Newton, nobody else. The collapse of the Soviet Union? Why, that was none other than Gorbachev.

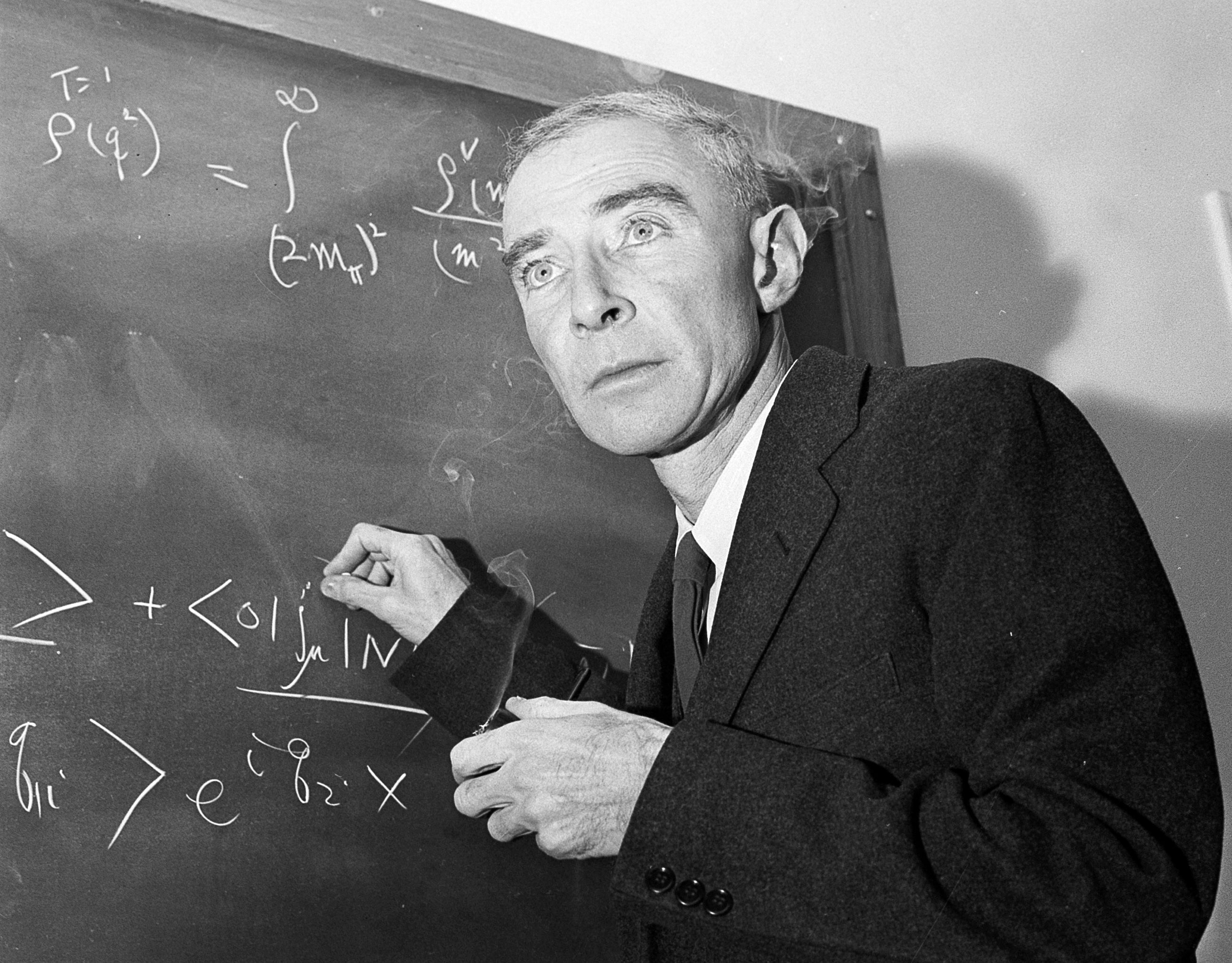

Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than with the coverage surrounding the release of Christopher Nolan’s new epic, Oppenheimer. Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past fortnight – or are solely interested in Barbie – the film is a biopic of American physicist J Robert Oppenheimer, who was the director of the laboratory in New Mexico where the first atomic bomb was developed. As a result, Oppenheimer is often labelled the “father of the atomic bomb”.

So firmly has this label stuck, surely to be further cemented by Nolan’s film, that it is gospel the first nuke was essentially the product of one great man. It hasn’t hurt that, because of his mysticism, pacifism, sexual liberation and left-wing politics, a cult of personality has built up around Oppenheimer. This has increased that sense of individualism, because the notion that the atomic bomb was singly fathered by a quirky genius is incredibly seductive.

But the problem with the great man theory is that it seldom holds water, and nowhere is it more leaky than with Oppenheimer. To regard him as the “father of the atomic bomb” is to ignore not only that the Manhattan Project was the result of a historically unprecedented level of teamwork, but also those others who are equally deserving of atomic fatherhood status. Although there is no doubt that Oppenheimer’s intellect, drive and knowledge were vital for the development of the bomb, the bomb would still have been invented without him.

Warning from Einstein

The origins of the atomic bomb certainly do not lie in the labs of Los Alamos, but rather in those of the German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, who in 1938 found that they had released barium after bombarding uranium with neutrons. What they had achieved was nuclear fission – splitting the atom in layman’s terms – but it took the physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch to realise this, and Frisch was able to replicate the experiment the following year.

News travelled quickly through the scientific community, and in January 1939, nuclear fission was achieved for the first time in the United States at Columbia University by a team led by the Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi. Although Fermi was the first to warn the US military about the consequences of the discovery, his words were largely unheeded. It would take a letter from Einstein and other physicists sent to Roosevelt in August that year warning that Germany could develop an atomic weapon, that finally spurred the Americans into kickstarting an atomic programme, which would later result in the establishment of the Manhattan Project.

It should be stressed that, at this time, Oppenheimer was not involved in research into nuclear fission. In fact, he was producing papers on astrophysics and subjects such as neutron stars. Even though nuclear weapons had only been theorised, if you were to ask anybody in the scientific community at the time who might become the “father of the atomic bomb”, they might have said Enrico Fermi, as he was the first to warn of the military application of what he had seen on his workbench at Columbia. Indeed, it is partly for this reason that Fermi is often rightly considered the “architect of the nuclear age”.

But no scientist in the world – not even Fermi or Einstein, let alone Oppenheimer – would have been able to develop the atomic bomb in his laboratory. As the Americans were to learn, constructing the first nuke was going to take an enormous amount of political will, cash and – crucially – administrative expertise.

Two pioneers

Administrators seldom make topics for biopics, and while that of course makes artistic and commercial sense, it means that a vital component of the historical story goes largely untold.

However, if Christopher Nolan were ever permitted to make a movie about those whose paternity of the atomic bomb perhaps exceeded that of Oppenheimer, then he would do well to look at the careers of two men whose names are today largely unknown – Vannevar Bush and Leslie Groves.

There is no space here to relate the byzantine series of committees and organisations established in the wake of Roosevelt receiving Einstein’s letter, but one department that was instrumental was the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), headed by Vannevar Bush, a scientific administrator and inventor who had already headed several prestigious scientific bodies. It was Bush who, in 1941, was absolutely tireless in lobbying the US government to embark on an accelerated programme to develop the atomic bomb. It is no exaggeration to state that, without Bush, it is doubtful that the bomb would have been developed before it was necessary for the Americans to launch a full-scale and bloody assault on the Japanese mainland.

Bush’s job was phenomenally difficult, not least because he had to overcome competition from so many other agencies and departments, all of whom felt they were more deserving of their slice of the federal pie to help with the war effort. It certainly did not help that the Manhattan Project, which the OSRD would finally establish in 1942, had to be conducted in top secret and was also phenomenally expensive. It cost some $2bn – worth some $100bn today – and required some 130,000 workers spread in plants, laboratories and factories all across the United States.

A stroke of genius?

Bush was not one to accept the second rate, and when he felt that the project was not being run dynamically, he demanded that the War Department appoint a new head. In late summer of 1942, that role landed on the shoulder of army officer Leslie R Groves. A veteran of the army’s construction division, Brigadier-General Groves had been proving his administrative worth during the construction of the Pentagon, and he was deemed a suitable candidate for a job that he was told – if he did it right – “would win the war”.

Although Groves was emphatically not the type of tortured genius that would make the subject of a great biopic, he was an administrative wizard who had an undeniable skill for delegating to the right man. And when Groves wanted the right man to head up the laboratory at Los Alamos, he found him. That man was, of course, Oppenheimer, who Groves identified as having the right qualities to head up the scientific development of the bomb. There were many who were against the appointment – not least because Oppenheimer was regarded as a potential security risk – but Groves was adamant. As one physicist later cattily observed, the appointment was “a real stroke of genius on the part of General Groves, who was not generally considered to be a genius”.

Ultimately, the project to develop the atomic bomb had many fathers – and indeed mothers. While Oppenheimer was certainly one of them, there were others who had started the project before he had. Vannevar Bush surely deserves equal status, a man of whom it was once said that “of the men whose death in the summer of 1940 would have been the greatest calamity for America, the president is first, and Dr Bush would be second or third”.

What the Manhattan Project shows us is that the great man theory only really works in the movies. Oppenheimer’s role in changing the world was undoubtedly massive, but there are other equally great men and women who surely deserve their share of parenthood.

Guy Walters is a historian and author.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks