Inside Nato’s ‘museum of shame’ where Lenin planned bloody revolution

John Kampfner unfurls the extraordinary history of the former Soviet workers’ hall in Finland – which has become a deep source of embarrassment and controversy to a nation that neighbours Russia

Welcome to the most hated museum in Finland.” This is not the usual greeting from the director of a museum, but Kalle Kallio is facing an uphill battle to keep his in existence.

It is not surprising that a museum named after the leader of the Bolshevik revolution might not go down a treat in a country that has just joined Nato, but that is the lot of the Lenin Museum in Tampere.

Indeed, visitors to Finland’s third city might not even know it’s there. The local authorities fund it but they also seem embarrassed by it. Go onto the website of Visit Tampere and you’ll find information on the cathedral, the open-air saunas, the museum of labour, a spy museum – even a museum dedicated to the Moomins. Lenin barely gets a look-in.

This is all the more curious given that, back in the day, thousands of loyal Soviet citizens flocked over the border in organised groups to pay homage to him.

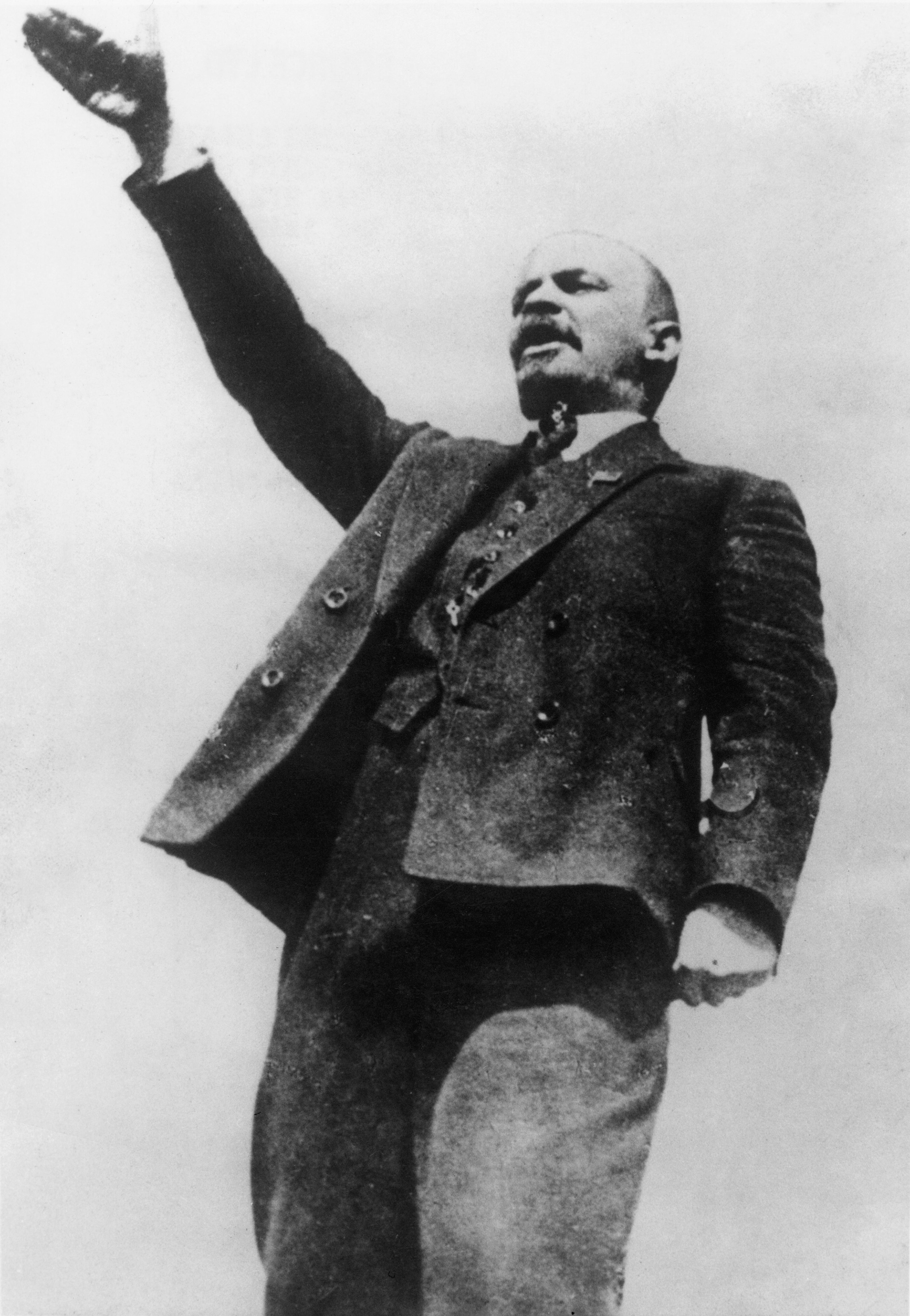

There is nothing random about the location of the museum. It was here, or rather in the workers’ hall that it now occupies, where Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and a small band of revolutionaries came together in December 1905 to hatch their plans. One of the attendees was a certain Joseph Dzhugashvili, aka Stalin, a twenty-something firebrand from the Caucasus, whose job it was to organise hijackings and bank robberies to help fund the movement.

This was the first wave of Bolshevism. Russia had lost its war with Japan; uprisings had taken place across the country, only to be put down by Tsar Nicholas II. Lenin had wanted to hold his meeting in St Petersburg, but that was deemed too risky in the febrile atmosphere. Though part of the Russian Empire, Finland enjoyed relative autonomy and was considered a safe haven. Its border at the time was less than 20 miles from the Russian capital.

Tampere was a proud industrial city, famous for its cotton mills (it still likes to call itself the Manchester of Finland) and foundries. Workers’ councils had briefly taken over the town; there was no Russian garrison stationed there.

“You can say that this was the birthplace of the Soviet Union,” Kallio tells me, as he points out the items on display. This includes a series of photographs of the young comrades practising shooting in the nearby forests and a mock-up newsreel of the secret gathering. The narrator describes how Lenin went to Tampere’s market square and was so impressed with the display that he declared: “People who make black sausage like this deserve their independence.” Except there is no record of him actually saying it.

This is one of the many curiosities of this museum; it attempts to be serious and humorous, factual and fictional. Its strength lies less in its depiction of Lenin, or of those heady days in 1905, than in what it says about Finland’s very peculiar relationship with Russia.

After the downfall of the Romanov dynasty in 1917 and the defeat of the Germans a year later, Finland was in limbo. Legend has it, or rather had it, that Lenin granted the Finns their independence partly as gratitude for harbouring him in the years leading up to the revolution.

During the Second World War, Finland found itself fighting on all fronts, but for most of the time, it allied itself with the Nazis. Remarkably, it was the only country neighbouring the USSR that was not forcibly taken over in 1945. It was required to cede a tenth of its territory and to pay heavy reparations, but it retained its independence. This came at a price; neutrality tinged with heavy subservience to the Kremlin. This was subsequently to be known as Finlandisation.

“We had to show that our foreign policy had changed,” Kalio says. “We had been with the Germans in the war. Establishing a Lenin Museum was one way of showing that we were prepared to start afresh.”

The museum opened its doors in January 1946 before an audience of Soviet and Finnish dignitaries. Almost all its exhibits had been provided by institutions from Moscow. Over the next three decades, Nikita Khrushchev came to visit, as did his successor Leonid Brezhnev, and the cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. Visitors were always reminded of the helping hand rendered by Finland to Lenin. This had the dual purpose of cementing bilateral ties – and ensuring the continuation of the museum.

In 1970, on the 100th anniversary of Lenin’s birth, more than a thousand events, conferences and celebrations were organised across Finland.

Then came 1991, the collapse of Communism and dissolution of the Soviet state. With change hurtling through Moscow, the museum’s then director jokingly suggested that if Lenin’s embalmed body was to be moved from his mausoleum on Red Square it might as well come to Tampere. Western and Russian journalists took him seriously and it briefly became a hot news story.

Finland was left disoriented. While there was great relief that the Cold War had come to an end, the country’s economy, so dependent on trade with Russia, went into a tailspin.

The museum quickly changed its content, introducing new items about Stalin’s purges and other dark periods of Soviet history. A diorama details the location of all the gulags scattered across remote parts of the country. The Soviet era was also represented through kitsch and humour. A mannequin of a confused-looking Stalin in military uniform stands next to a smiling Lenin on an early 20th-century motorbike.

Nevertheless, criticism grew in the Finnish media; politicians, journalists and much of the public again questioned the museum’s existence. In 2014, with finances ever tighter, it was taken over by Tampere’s larger Labour Museum. Kallio was named director. Visitor numbers are, at 12,000 per year, not particularly impressive, but they are apparently stable.

As Vladimir Putin tightened his grip on Russia and annexed Crimea in 2014, the rumblings started again. After Russia’s fully fledged invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Finland suddenly switched from dove to hawk. It applied to join Nato, increased defence spending and closed its borders with Russia. All talk of good relations was banished. Social media clamoured to have the museum closed.

Kallio insists such a decision would be historically illiterate and inconsistent. Even though Lenin statues were quickly taken down after the invasion in the cities of Turku and Kotka, Helsinki still has a Lenin Park. In any case, he argues: “People, if they actually came here, would see that it tells the story of the Soviet Union. It’s not a temple to Lenin, or Communism, or to Putin.”

For me, the most important message of the museum is the obsequiousness and the dependency that was required of Finland just to keep Russian forces at bay. Now the country has flipped 180 degrees. That story is worth telling, but it may be too painful for some to dwell on.

Towards the end of this year, Kallio plans a revamp. The kitsch will be replaced by the horrors of Putin. He is resilient and resourceful, looking for marketing opportunities wherever he can find them. He has taken to calling it: “The only Lenin Museum in Nato.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks