The last British ship in the Falklands and its dissident captain

The official UK government line was that Argentina’s invasion in April 1982 came as a complete surprise. The lone navy officer to raise the alarm was deemed a ‘loose cannon’ for his troubles, writes Liam James

The decision was taken in 1981 to end Britain’s naval presence in the South Atlantic. Given the sum total of that presence was a small ice patrol vessel named HMS Endurance, this decision might have seemed an insignificant part of the defence review that year which condemned around a fifth of the royal navy’s warships.

But the South Atlantic is home to the Falkland Islands, a British archipelago that had long been the subject of a bitter territorial dispute with nearby Argentina, and in choosing to scrap its lone ship based in the region Britain had signalled that it would not, seemingly even could not, fight to defend its claim to the islands.

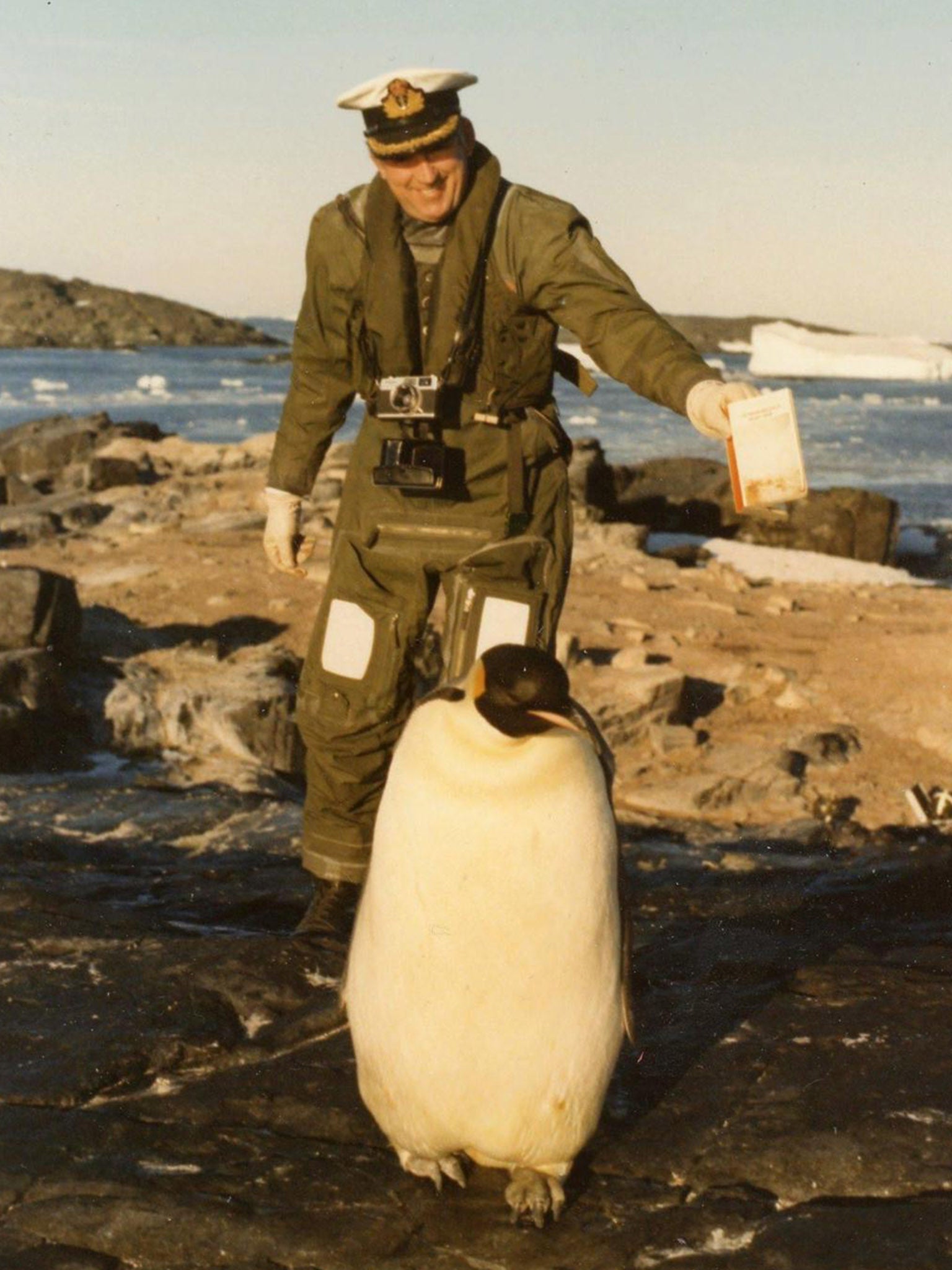

The captain of the Endurance, Nicholas Barker, recognised this and warned London that minds in Buenos Aires were turning towards taking the Falklands by force. Within a year Argentina had invaded, starting a conflict in which nearly a thousand people were killed.

Captain Barker campaigned to save his ship and stop the war, going on to be highly critical of the British government after the invasion. His stance cost him his career – Endurance ended up remaining in service longer than he did – but he maintained that the Falklands conflict of 1982 was avoidable up until his death 15 years later.

Endurance condemned

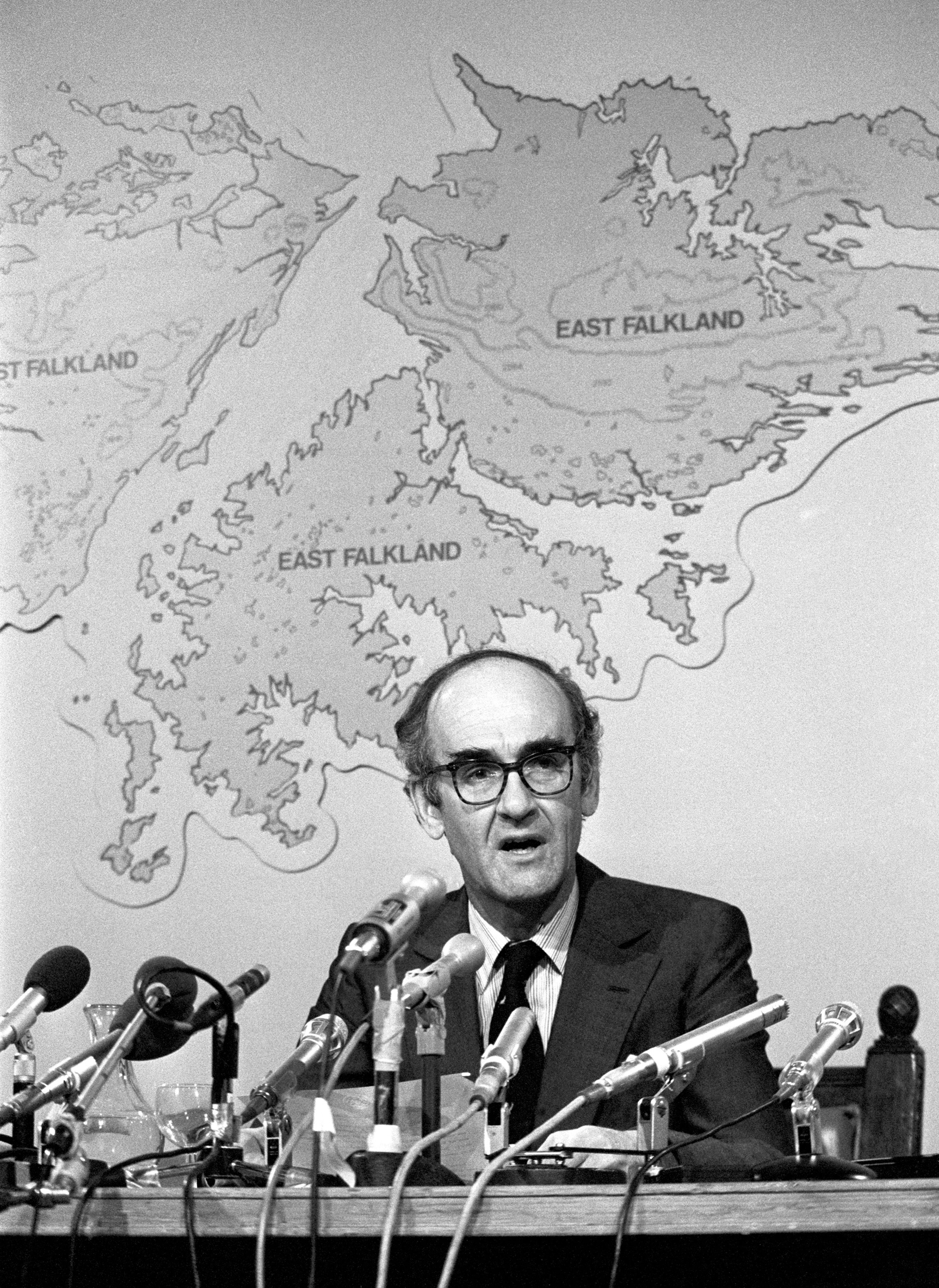

At the start of 1981, John Nott took up the role of defence secretary in Margaret Thatcher’s government with a brief to make enormous savings in the military budget.

Britain was in a sorry economic position but was planning an expensive military overhaul to meet the threats of the day – the government had its eye on a new nuclear weapons system, Trident, that was being touted by the US, for instance. There was a need to free up money from somewhere and Nott was convinced the navy was the most appropriate target of cuts that were ordered for that June.

He lined up nine of Britain’s 59 frigates and destroyers and one of its three aircraft carriers for decommissioning, among others. Endurance, a ship of modest combat strength that was used for conducting scientific surveys in the ice-topped waters of Antarctica, was added to the list to spare losing another prime battleship. Besides its scientific work, Endurance was otherwise valuable to the British state as it gathered intelligence and carried out diplomatic functions around South America. Even so, Nott’s mind was set on decommissioning the ship.

The people of the Falklands were disturbed. As Capt Barker put it, Endurance was “a symbol of British presence in the South Atlantic and the one and only reassurance to the islanders that Britain, 8,000 miles away, still cared”.

Now Britain had decided to scrap this key guarantor of their security at a time when the military government that ruled Argentina was growing frustrated due to a lack of progress in long-running negotiations over ownership of the islands – known in Buenos Aires as Las Malvinas.

On hearing of the plan to scrap Endurance the islanders wrote to the then foreign secretary Lord Carrington to say: “The people of the Falkland Islands deplore in the strongest terms the decision to withdraw HMS Endurance from service. They express extreme concern that Britain appears to be abandoning its defence of British interests in the South Atlantic and Antarctic at a time when other powers are strengthening their position in these areas. They feel that such a withdrawal will further weaken British sovereignty in this area in the eyes not only of Islanders but of the world.”

Carrington himself was against Nott and lobbied him unsuccessfully to reconsider, as did several others in both houses of parliament.

Endurance was set to be withdrawn from service on 15 April 1982, two weeks after what came to be the date of the Argentinian invasion.

Stop the war

In the summer of 1981, Endurance was in Britain for maintenance works before setting off on what was planned to be its final voyage. Sandy Saunders, a crew member from 1980 to 1982, says everyone on board was sure there would be a conflict over the Falklands within a year or two.

He recalls Capt Barker’s efforts to warn London that scrapping Endurance would prove to be a grave error: “He lobbied all who would listen to try to get the message across that in Argentina he had been told by several senior Argentine officers that the ‘Malvinas’ was a common subject for discussion and how they were going to persist to get leaseback or any method imaginable to gain control of the islands.”

Leaseback was an arrangement favoured by London whereby sovereignty of the Falklands would be granted to Argentina but the British administration familiar to the almost entirely British population of the islands would continue to hold power for at least a couple of generations. It was similar to the later “One Country, Two Systems” principle that was at least agreed to be a condition of the British handover of Hong Kong to China.

While Capt Barker was dashing around London trying to catch an attentive ear, the junta, or military government, in Argentina was impatiently waiting for yet another round of negotiations after Britain failed to get approval for leaseback from the Falklands population. The frustration of the Argentinians was apparent to many in London but Nott still did not consider changing course.

Captain Barker, in a posthumously published memoir of his naval career, said that “John Nott was a hatchet man” who was not concerned with the views of those in the forces he had been appointed to chop up. “He had the advantage of being able to rely on powerful political allies and the civil service. None of them had much respect for the intellect of senior serving officers,” he said.

After the captain failed to raise alarm that summer, Sandy said, he “was told ‘to return to his ship and get on with being commanding officer or resign his commission’.”

The ‘final’ voyage

The Endurance sailed south from Portsmouth in October of 1981 for what was thought to be the last time.

The trip was scheduled to run like so many previous. On the way to the Falklands it stopped off at Madeira, Rio de Janiero, the Uruguayan capital of Montevideo and the Argentinian ports of Buenos Aires and Bahia Blanca.

At the last stop, Sandy recalls, the Endurance crew crossed paths with the Argentinian warship General Belgrano. The two crews played football against one another and Endurance won 5-2, in the first match at least.

Sandy said: “I turned up with the rugby team the next day and was told, by a suave lieutenant commander with slicked back hair and a public school English accent that ‘there will be no rugby’. So, we had [another] kick around on the grass in front of the stadium and went home (moral) victors.”

Within a year Britain had sunk the Belgrano, killing 368 crew members in what remains its most controversial act of the conflict.

After Bahia Blanca, Endurance sailed on, arriving in the Falklands early in December before setting off again on trips around the South Atlantic. Encounters with the Argentinian navy were far from uncommon. Just months before Argentina invaded Britain’s territory, the armed forces of the two countries were glad to make each other’s company.

Sandy says an Endurance trip to the neutral Antarctic island of Marambio at the same time that 40 visiting Argentine soldiers were being flown in was “a very sociable event”. “The guests were picked up by their Chinook, piloted by a man who had been drinking on board, a very skilful operation.”

From Capt Barker’s position though, it was clear something was amiss.

In War Stories, a BBC documentary from the early 1990s, Capt Barker recalled: “This year things were different.” A portside meeting in Buenos Aires in November gave him an early sign that he had been right to expect a shift in the Argentinian position.

He said: “I swapped ships’ itineraries with my Argentine opposite number, Captain Trombetta. He told me he was going to Antarctica but three weeks later he showed up illegally on the British island of South Georgia.

“He lied to me. Why? I reported this to London.”

The landing on South Georgia – an island a few hundred miles to the west of the Falklands that was also claimed by Argentina – caused a diplomatic stir. Britain had commissioned scrap metal merchant Constantino Davidoff to work on the island but had not approved his mode of transport: an Argentinian navy vessel. The British ambassador to Buenos Aires complained to the junta but little more was done as Britain was keen not to escalate while tension over negotiations was high.

In January, Capt Barker had an encounter on Argentina’s closest base to the Falkland Islands, Ushuaia, that left him in no doubt the diplomatic situation was soon to devolve. He said: “I was snubbed by the Argentine base commander. His deputy said they had been ordered not to fraternise with the British.” The captain said he was warned by a friendly pilot that a war was coming, a warning he relayed to London.

Five days later the Endurance was in Punta Arenas in Chile, a country friendly to Britain that was locked in its own territorial dispute with Argentina. There, Capt Barker said “my Chilean naval friends told me about the Argentines’ intention to invade the Falklands. Once again I reported all of this to London but there was no response.”

The government in London was soon faced with a diplomatic crisis when Davidoff returned for a second work trip to South Georgia, again transported by the Argentinian navy. Endurance was sent to investigate. Capt Barker was sure it was nothing less than an attempt to establish a permanent Argentinian naval presence in the island. The landing took place on 19 March, just under two weeks before the invasion of the Falkland Islands. Britain’s official line is that the government did not know an invasion was coming until the last minute.

Had Capt Barker’s warnings been ignored as they were in the summer? Lord Luce, the foreign office minister responsible for the Falklands at the time, claims the warnings never reached the right people.

Unfortunately, the material that could remove doubt from the matter is inaccessible. While most of the government’s Falklands war records were declassified in 2012 under the 30-year rule, Capt Barker’s archives remain closed pending a now long-overdue review by the Ministry of Defence.

Critical captain

After the war began Endurance docked in the Falklands, later returning to sea where it fought against Argentinian forces. It forced the final Argentinian surrender of the war on the small island of South Thule on 17 June. Nott’s decision to scrap the ship was overturned and it served until 1991.

Shortly after the war was over Capt Barker gave an interview to the press in which he said that Britain had given Argentina a “green light” to invade. On returning to Britain he was ordered to keep quiet and toe the line in public but his reputation for being difficult was already firm.

One of his sons, Ben Barker, reflects: “I think he was quite literally seen as a loose cannon after the war. The navy didn’t seem to know what to do with him. I think they wanted him out of uniform and away from naval establishments.”

The captain gave evidence to the Franks inquiry, the government review that went on to find that neither Thatcher, Nott nor anyone else in power could have foreseen the invasion. Capt Barker said it was “a whitewash, another Whitehall farce”. He left the navy in 1988 and retired to northeast England, having spent his final years of work as a diminished figure in the service. Thousands of miles away, however, he had the reputation of an honourable defender who had tried his best to stop the war, only to be left standing alone as it began.

“After his death in 1997, the Falkland islanders chose to dedicate a memorial plaque to him in Christ Church Cathedral, Port Stanley,” Ben Barker says. “An underwater pinnacle off James Ross Island was named Barker Bank and a small tussock-covered island off South Georgia was posthumously named Barker Island by the UK’s Antarctic Place Names Committee in 2009.

“Dare I say it, I’ve looked but I can’t find an island named after Margaret Thatcher or John Nott!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments