Cash and dishonours: an inglorious history of celebrity bank Coutts

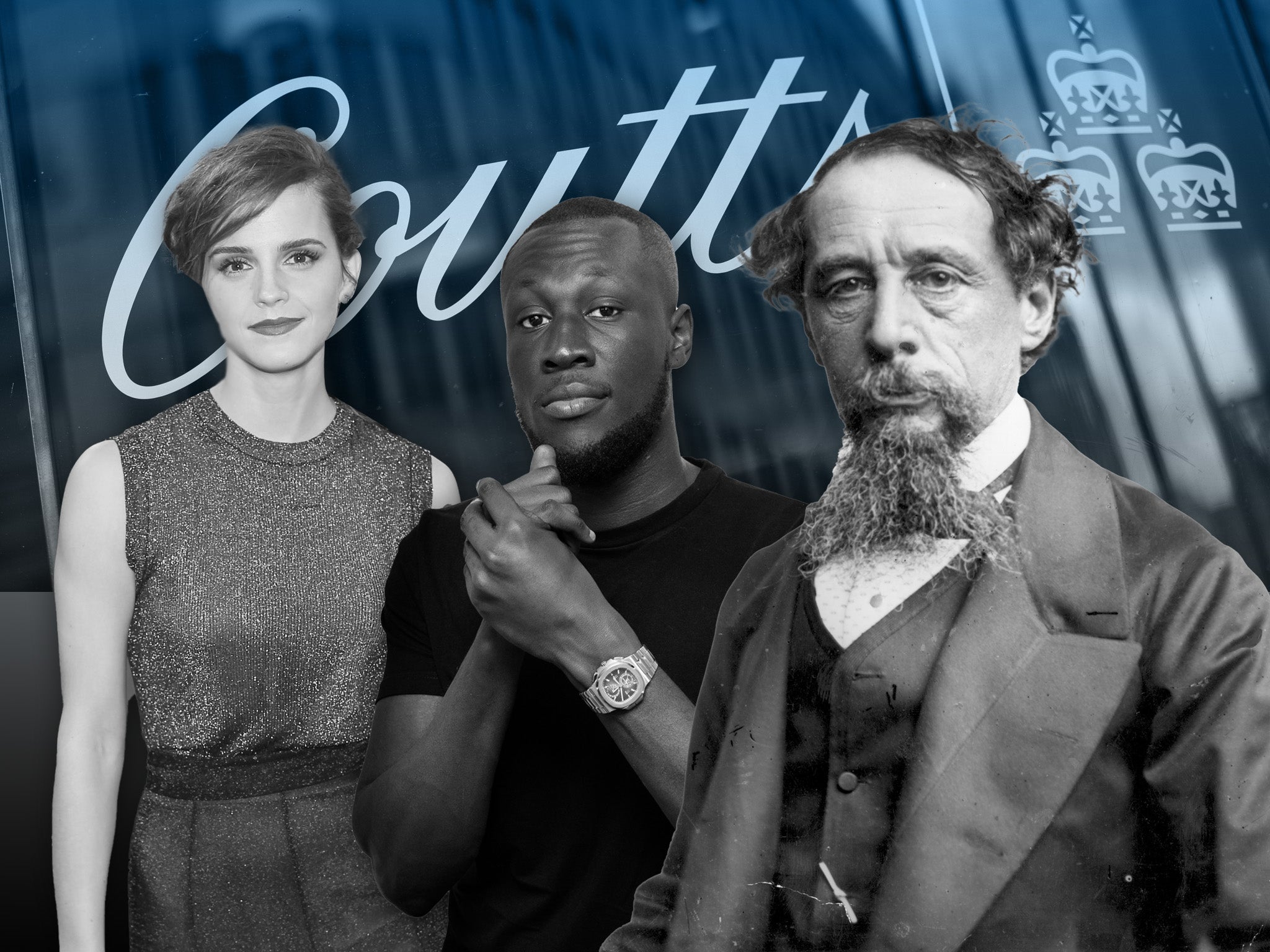

Despite the eye-popping perks and glittering roster of clients from Charles Dickens to Emma Watson, the history of Coutts is not as it seeks to portray, writes Guy Walters. The Farage furore is simply the latest in a line of scandals stretching back centuries

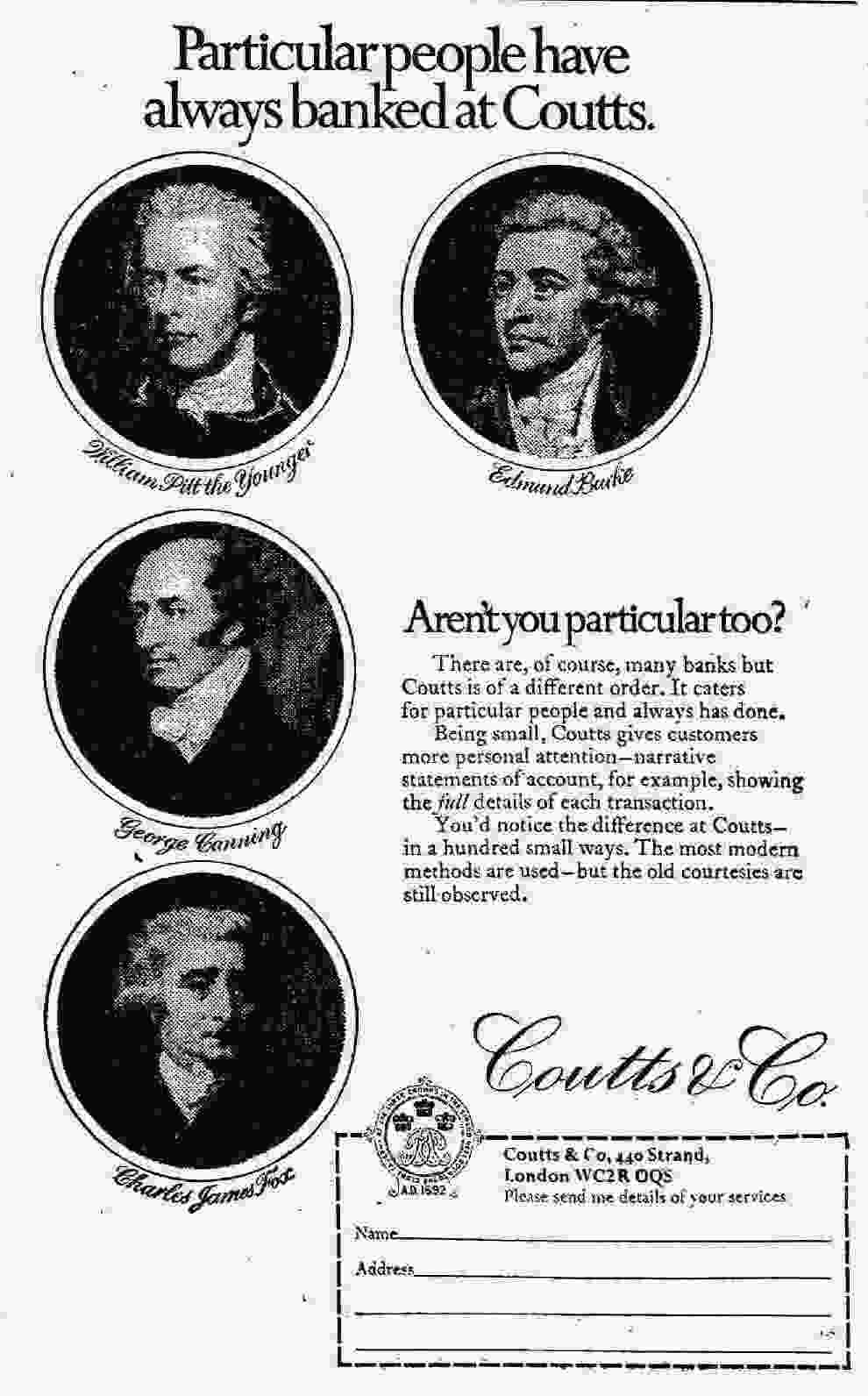

Back in 1970, Coutts ran one of those insufferably smug advertising campaigns in broadsheet newspapers that would not sit well in these supposedly more egalitarian times. Featuring William Pitt the Younger, Edmund Burke, George Canning and Charles James Fox, the advert was headlined, “Particular people have always banked at Coutts”, and then went on to ask, “Aren’t you particular, too?”

It’s that sense of clublike oh-so-exclusive specialness that Coutts has always tried to foster throughout its 331-year history, despite the fact that it is, after all, merely a place to deposit or borrow money. That same smugness still permeates its promotional efforts, with the bank’s website liberally peppered with ghastly claims of “supporting the world’s most exceptional people”, and “banking the best and brightest for over three hundred years”.

I should declare that I too was once one of those exceptional people, because I opened an account with Coutts when I started at Eton in 1984. The bank had its only branch outside London down the high street, which was clearly a smart move to grab the custom of future grandees while they were still pubescent. Like pupils, the bank’s staff wore tailcoats, which even back then seemed desperately ingratiating.

I shall never forget the manager’s deep disappointment when my mother informed him that there was no family trust fund for him to get his mitts on, and his patronising response that our facility would therefore be a “cornflakes account”. I closed it a few years later – or perhaps the bank closed it – when my student overdraft made me about as welcome as Nigel Farage.

To be fair to Coutts, and in order not to sound too chippy, its roster of customers over the past three centuries is pretty damn A-list, including every king and queen since Queen Anne, Charles Dickens, the Duke of Wellington, Chopin, The Beatles, Nelson, and, more recently, Emma Watson and Stormzy. Dracula apparently banked with Coutts, doubtless taking advantage of its 24-hour banking facilities.

I also happen to know that a certain supermodel is a customer because I saw her debit card when I was behind her in the queue for the till at a branch of the Early Learning Centre about 15 years ago. I mention this because there’s a certain frisson engendered when you see that someone banks with Coutts – it tells you that they’ve arrived, although it should be acknowledged that famous models don’t really need a Coutts card to engender a frisson.

What the bank’s customers may not be aware of is that the history of Coutts is nothing like as gilded as it likes to portray, and the latest furore over Farage is simply the latest in a line of scandals and cock-ups that stretches back for centuries.

Take, for example, the case of James Coutts, who married the granddaughter of the bank’s founder, John Campbell, in 1755. He was made a partner, and then appointed his brother Thomas into the business. James really was not cut out for banking, and was once described as being “unpolished in manners, passionate, and resentful”, and by his own admission was “unfit for deep study”. As MP for Edinburgh, he proved himself to be a spectacularly hopeless performer in the House, and was even told by a friend, “My dear Sir you are by no means qualified for speaking”, and was advised never to speak again. He would soon lose his seat, and in 1774, his brother ousted him from the bank because he was “an improper person to be connected with such a business”. He decided to go on a tour of the continent; when he was in Turin he was incarcerated for violent behaviour, and died in Gibraltar in 1778 while still under guard.

Strangely, the story of the man after whom the bank is named does not feature on the history section of the Coutts website. And neither do some anecdotes about his brother, Thomas, who became the sole proprietor of the bank after James was booted off. Described as being “plain in his person, sedate in his deportment, frugal and sparing in his personal expenditure”, he had a habit of wooing noblemen as customers by offering them vast unsecured loans in cash. On one occasion he produced 30 £1,000 notes – worth around £4,250,000 today – and presented them to a peer with only a “note of hand” as security.

Word spread, and soon King George III was a customer – although not for long. In 1804, Thomas Coutts’s son-in-law, the radical MP Sir Francis Burdett, was fighting to regain his Middlesex seat because the result in the constituency in the 1802 general election had been declared void, and Sir Francis lost the ensuing by-election because of the corruption of the returning officer. In order to help fund his fight, Thomas Coutts lent his son-in-law £100,000 – around £9.5m today. News of the loan soon came to the king’s attention, who summoned Coutts, told him that he had no time for radicals such as Sir Francis, and withdrew all his money from the bank. To make matters worse, the government is also thought to have withdrawn all its funds from the care of Coutts because of the connection with Sir Francis.

When Thomas’s wife died, the 79-year-old banker did what so many old widowers have done since time immemorial – marry a younger woman. In this case, the woman was an actress called Harriot Mellon, who was 40 years his junior, and the couple were married in January 1815 just four days after the death of Coutts’s first wife. Unsurprisingly, the union attracted much public ridicule. After his death, the new Mrs Coutts inherited his entire wealth of £900,000 – around £100m today – although she in turn would leave that wealth to one of Thomas’s granddaughters, Angela Burdett, the daughter of Sir Francis.

In her will, Harriot stipulated that Angela must add the name Coutts to her own, but more bizarrely, insisted that she would have to give up her wealth if she married a foreigner. It was this clause that was to cause the next headache for the family and its business, as in 1871, the 67-year-old Angela – who had been created a peer in her own right for all her philanthropic work – decided to marry a 29-year-old American called William Bartlett. After much legal toing-and-froing, Angela had to give up 60 per cent of her massive fortune to her sister.

More recent history has seen Coutts in trouble for malpractice. In 2012, the bank was fined £8.75m by the Financial Services Authority (FSA) for severe breaches of money-laundering regulations. “Coutts’s failings were significant, widespread and unacceptable,” said the FSA, and the bank only wriggled out of a much larger fine because it managed to settle before the investigation had run its course. The bank was lucky, not least because it had already received a fine of £6.3m from the FSA the previous year, for misselling a fund. Not that the bank really seemed to learn, because just five years later, in 2017, it was the turn of the Swiss to fine Coutts for once more breaching money-laundering regulations, and the bank had to cough up £5.8m in Swiss francs.

Then of course there is the case of Coutts handling €3m in cash which had been given to the then Prince of Wales for his Prince of Wales’s Charitable Fund (PWCF) in 2015 from a senior Qatari politician. Coutts apparently received the cash in denominations of €500 notes in Fortnum & Mason carrier bags. Although nothing illegal had taken place, the donation certainly raised eyebrows when it was made public and showed that the bank was willing to do for royalty what it might not do for customers who are perhaps not quite so “particular”.

But despite the bank’s occasional dodginess, its customers still appear to love being part of the Coutts “club”. At its most basic, the cachet of having a Coutts account lies in the fact that it tells people that you are rich, and flashing your cash appears never to go out of fashion.

Doubtless customers try to kid themselves that they’re actually with Coutts for all the goodies that the bank offers, such as a concierge service that sources hard-to-get tickets and apparently will help organise your stag night in a European capital, or even get hold of an elephant for a wedding reception.

By regarding Farage as having an unsavoury reputation, Coutts was essentially the pot calling the kettle black. Ultimately, the former Ukip leader might be better off with a cornflakes account at a regular high street bank.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks