Life in the frozen north: Native Canadians fight history, and each other, to save their language

In a remote community in northeastern Quebec, Rachel Savage meets the group of indigenous Canadian women finding themselves through their language

When she was a child, Cheyenne Vachon’s grandfather asked her to fetch water. She continued to play, bouncing a ball up and down on a paddle. By the time she got around to doing the chore, her grandfather had already got the water himself. “He said, ‘Sit down, I’m going to tell you a story.’ And I said, ‘Oh god, not again.’”

The story was about a family of Naskapis, the indigenous Canadian First Nation that Ms Vachon’s mother belonged to, in the bush in the days when they were still nomadic. A hunter was about to return with his catch and there was excitement in the air at the prospect of days of hunger coming to an end. The boys set about chopping wood and the women got ready to prepare the caribou. But the young girl of the family did not fetch water for cooking the meat and making broth for the babies and sick elders, as she was supposed to. By the time the rest of the family realised, it was too late. As a result, the young girl’s seriously ill grandmother died.

It was always the way with Ms Vachon’s grandfather, when she was growing up in the close-knit native reservations that border Schefferville, a small, remote mining town in northeastern Quebec. Instead of punishing her, he would tell stories. But she never understood why. Not until her late thirties, when she was studying Naskapi language as part of a teacher training course run by the prestigious McGill University.

“We were listening to a recording an elder had made, and we were listening for language and the words,” says Ms Vachon, now 43. “But when I listened to it I just saw the lesson, what the elder was trying to teach the person he was talking to… It’s as if a light went on and I could see everything.”

“All these stories, my grandfather was teaching me about respect, he was teaching me about empathy, he was teaching me about being courageous,” she says. The story of the girl who failed to fetch the water, for example, was about responsibility, about every Naskapi having a role in ensuring their survival in an often harsh migratory existence.

But, for Ms Vachon, this realisation was about more than understanding her grandfather’s stories, more than improving her native language skills.

“The legends, the teachings I’d heard as a child, it was as if they became alive,” she says. “They weren’t just words any more, they weren’t just broken pieces of information. And for the very first time I felt like I belonged.”

Ms Vachon, who runs a community women’s shelter, has not been alone in her awakening. Other Naskapis are finding themselves, reconnecting with their language and culture or forging a link that never existed. But it is an uphill struggle for a community that numbered just 1,356 people in 2017 and has suffered decades of discrimination and disconnect from their traditional ways of life. That is trying, against the odds, to improve its education. And that is divided on the best way to use scarce resources to preserve and revive its traditions.

The Naskapis were probably the last indigenous group in Canada’s Quebec and Labrador peninsula to be contacted by Europeans, the result of following caribou herds across vast tracts of wilderness. Their population was small, fluctuating between 150 and 400 in the 19th century due to periods of starvation caused by fewer caribou, a cyclical phenomenon, and ammunition shortages. They were probably also the last group to give up a nomadic lifestyle, corralled by the Canadian government, some say forcibly, others say with the promise of jobs and education, into a bleak reservation outside the newly built iron ore town of Schefferville in 1956.

1,356

Kawawa’s population in 2017

But, even with their relatively late colonisation, the Naskapis, like other aboriginal Canadians, struggled to hold onto their culture. From their first contact with the UK’s Hudson Bay Company in 1831 they were encouraged to trap small mammals for the fur that had become so fashionable in Europe. At first they resisted. There was no need for them to trade with the British when the caribou provided them with everything they needed.

“They are the most deceitful, lying, thievish race of Indians I have ever dealt with, proud, independent,” complained Erland Erlandson, a HBC trader. The Naskapis had had the temerity to demand better trading terms, which they were granted in 1834.

But eventually the Naskapis came to depend on the ammunition they swapped for pelts. They were then at the mercy of first the company, and then the British and Canadian governments, which forced them to move hundreds of miles between trading posts without regard for the caribou migrations.

It was the move, though, into reservations in the mid-20th century that really weakened the connection of Naskapis and other indigenous groups to their language and culture. Not only had they lost much of their traditional lifestyle, but poverty and the accompanying alcoholism and domestic abuse strained family and community ties. Naskapi was not initially taught at the local school and many children were forcibly sent to residential schools “down south”, where they were forbidden to speak their language at all.

Self-governance in the 1980s brought positive change. The Naskapis had lived with another First Nation, the Innu, since their move to Schefferville. But while there is intermarriage and many cultural similarities, their languages are distinct. Naskapis also speak English as a second language, while the Innu, who were colonised by Jesuit missionaries, use French. In 1984 the Naskapis moved to a new reservation, Kawawachikamach, having negotiated a new treaty with the Quebec provincial government.

Kawawachikamach, known as Kawawa, also got its own school, Jimmy Sandy Memorial School, where Naskapi began to be taught. Initially the native language took a backseat to English. But in the mid-1990s Naskapi immersion was introduced from pre-kindergarten to grade 2 (ages 4 to 8).

The legends, the teachings I’d heard as a child, it was as if they became alive. They weren’t just words any more, they weren’t just broken pieces of information. And for the very first time I felt like I belonged

The walls of Shannon Uniam’s grade 1 classroom are papered with brightly coloured posters covered with the Naskapi syllabic script. She hands out slivers of cold, richly flavoured goose meat to her diminutive charges. “Goose week”, when Naskapis head into the bush to shoot Canada Geese as they migrate north to the Arctic, is around the corner and Ms Uniam is teaching the children about their traditions.

She moves to secondary 1, covering a Naskapi language class. At first, the 12 and 13-year-olds slump in their chairs as Ms Uniam reads a story about hunting. Then she fetches a marten pelt from her a classroom and they sit up, rapt, as she explains in Naskapi how it is trapped and prepared.

“Especially in high school, they’re searching for their identity,” Ms Uniam, 34, tells me later. “And that’s why I was saying to them, ‘Be proud of who you are, where we come from, and that we can still speak and write in our language.’”

“I want them to hear that from me. Because that’s who I am too.”

Most Naskapis are positive about the school’s native language immersion. And it is important for more than just preserving a means of communication. In a 2008-10 national survey, First Nation communities said substance abuse was their biggest challenge. Youth suicide rates in native communities are more than five times the Canadian average. But language and culture can be an antidote. Researchers have found that indigenous young people with a stronger connection to their heritage are less likely to abuse drugs or attempt suicide.

Nearly all Naskapis speak Naskapi as their first language. Naskapi-language education is not without its challenges, though. For one, Ms Uniam is in the minority. Only a quarter of Jimmy Sandy Memorial School’s 24 teachers are Naskapi. Ms Uniam was trained with 12 others, in the same McGill programme as Ms Vachon. It took place for three weeks annually, for four years from 2013, and was deliberately in Kawawa to ease the high attrition rates of indigenous people forced to move far from home for higher education.

However, only three of the McGill graduates are still teachers. Most of the staff at the school come from the south for just a couple of years in their mid-twenties. So children constantly have to get used to new, inexperienced teachers who know next to nothing about them or their first language.

There also aren’t many Naskapi-language teaching materials, which makes it hard to develop literacy, says headteacher Joseph Whelan.

“If you emphasise literacy, it doesn’t matter what the language is… students will understand the value and they’ll progress well,” he explains. “There aren’t a lot of books or other [materials] out there, so getting them to read in their mother tongue is difficult.”

Meanwhile, around 40 per cent of the 252 children at the school live in Schefferville or Matimekush, the Innu reservation. But, because of family ties, they are allowed to attend what is perceived to be a better school than their local one. They tend to grow up with Innu and French, so can find it hard to learn Naskapi and then English too. That makes the transition to mainly English in teaching in grade 3 harder still, even with an extra, language-focused year for some children.

“In grade 6 class most are reading two years below level, some are reading four years below,” says Mr Whelan, who has been at Jimmy Sandy Memorial School 10 years, two-and-a-half of them as headteacher.

“By the time they get to secondary 3 [age 14-15] they’re so many years behind, with so many years of feeling a lack of success, that they just don’t want to go on any more with their education.”

Last academic year there were 27 students in kindergarten. But only five students graduated from secondary 5, and it is often as few as three (there are some years, though, where no students finish high school in Matimekush).

The school is also struggling with other factors out of its control: children coming to school tired and hungry; families that shuttle between Kawawa and other communities, disrupting their children’s studies; a lack of educated parents and other role models who encourage and inspire.

“Any given day [students] might be coming from a situation that we can’t even imagine,” says Mr Whelan.

“It’s not uncommon for teachers to hear from their kids that they didn’t sleep all the night before. Mom and Dad were up all night, they had lots of friends over.”

The process of improving a whole community’s educational outcomes, and the emergence of role models like Ms Uniam, is therefore a slow, tortuous one. It is not helped by a divide in the community over how best to preserve and revive Naskapi, and thus improve their children’s literacy.

Bill and Norma Jean Jancewicz moved to Kawawa in 1988. Originally from the US state of Connecticut, they were missionaries, but not the usual kind. Part of Wycliffe Bible Translators, a non-denominational organisation whose members have worked on thousands of projects around the world, their mission was to help the Naskapis translate the Bible into their mother tongue.

“It felt like after first three years after living in the community, in homes of people, that I was kinda drowning,” Mr Jancewicz recalls. “But after four and then five years, it was then I felt I was starting to grasp what I was hearing and I was starting to be able to make myself understood.”

Naskapi, which is related to but distinct from Innu and other indigenous languages in the region, wasn’t even standardised. “Part of my first job was to analyse and describe the Naskapi language… the grammar of Naskapi was written by me,” says Mr Jancewicz, although he emphasised that this project and others were done collaboratively.

“I was an avid collector of anything in Naskapi. And there were a few elders in the community who were known to have written journals,” he says.

If you emphasise literacy, it doesn’t matter what the language is… students will understand the value and they’ll progress well. There aren’t a lot of books or other materials out there, so getting them to read in their mother tongue is difficult

“I would ask their permission to copy them… Some of them are just stories of their life and other things are more mundane, like a shopping list.”

Mr Jancewicz worked with the Naskapi Development Corporation, a government-established body which has a mandate to preserve the nation’s language and culture, from 1992. At first the couple subsisted on donations they raised themselves. Then the NDC hired Mr Jancewicz as a consultant, while Mrs Jancewicz worked at the school, teaching and developing their Naskapi curriculum.

In 1994 the NDC published the first Naskapi book, a short volume of stories about Jesus’s life. The same year a 10,000-word dictionary, which had been in the works for almost two decades, was finished. It is currently undergoing an expansion that could see the word count triple, says Mr Jancewicz, who now supports other First Nations with their own Bible translations. In 2007 the NDC finished translating the New Testament. Now, they are working on the Old Testament.

“My goal is to try to produce more things that people can read easily and understand, and to be able to get people interested in the Bible, to get to know God in their own language,” says Amanda Swappie, an NDC translator.

“It means a lot for the elders, because they want the whole Bible in their language.”

Kawawa’s church is packed for special occasions. But only 15-20 people attend regularly. Consequently, many in the community mutter that the NDC is wasting money on religious literature. That it should concentrate on materials for the school.

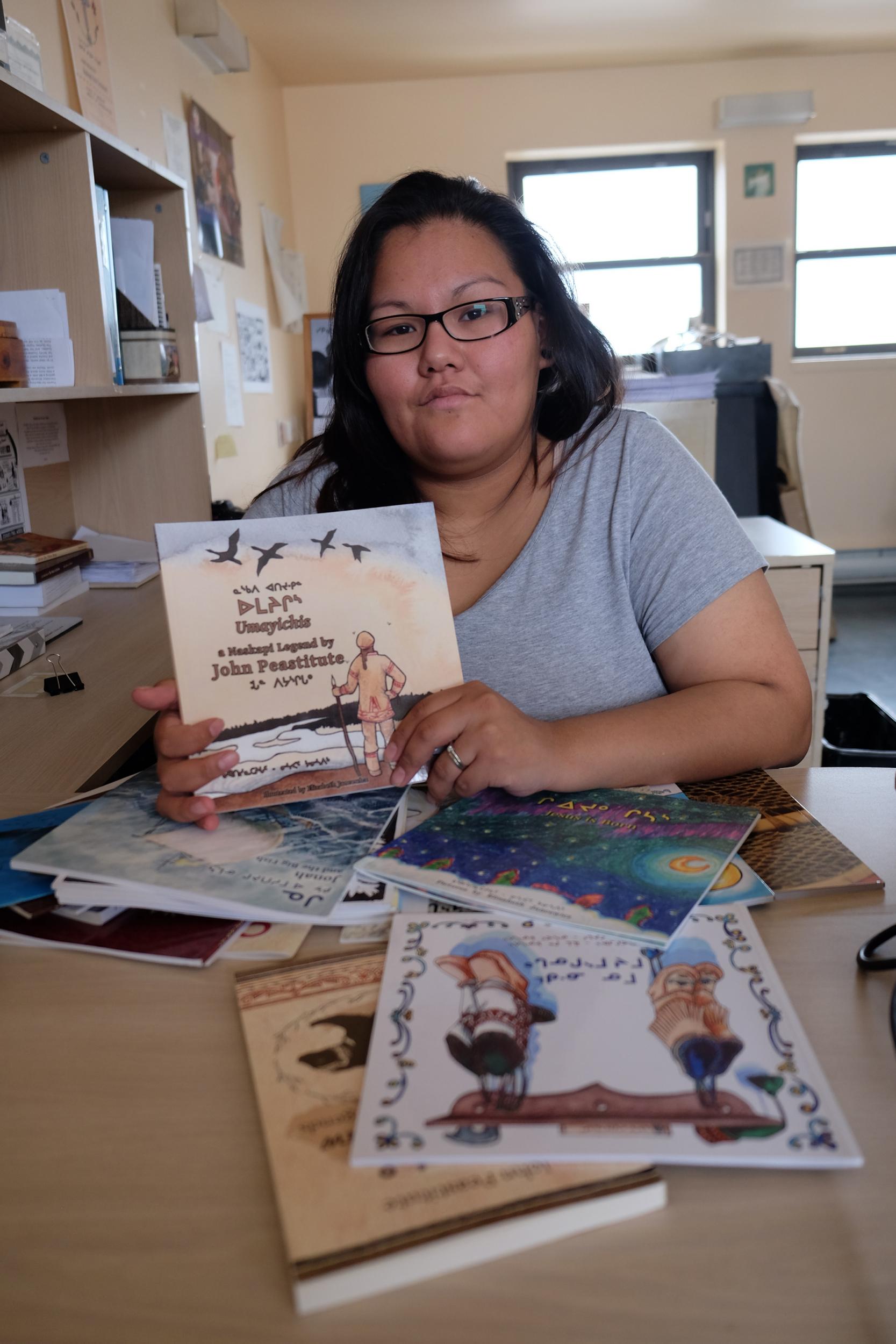

Ms Swappie and her colleagues point out that they have produced five books of Naskapi legends and a series of children’s stories. And they argue that they cannot work for free.

“I feel like our work is always being resisted,” says Ms Swappie. “A lot of people ask me for help with translation, but they do not want to use our materials.”

Political and personal differences, between those in the NDC and the Band Council, which runs most of Kawawa’s services and receives the bulk of government money, are to blame for much of the disagreement. Both NDC staff and councillors admit that the relationship has deteriorated in the past couple of decades.

But such a small community will always struggle to muster resources, whether for teaching, translation or anything else. Indeed, only two-thirds of Naskapis actually live in Kawawa. And, despite the divisions, Naskapis like Cheyenne Vachon, Shannon Uniam and Amanda Swappie are still managing to lead a language revival.

Ms Swappie tried to study criminology in Ottawa. But she struggled as a young mother and had to return home after less than a year when her funding was cut. Becoming a translator was almost accidental – a job posting happened to open up when she moved back. Now 27, she describes her work as “life-changing”. And she says she would eventually like to go back to university to study linguistics.

“It was the right time and it was the right place for me to be,” she says. “Because now I’m happy where I am. I love my job.”

“If we don’t know the language, if we can’t speak it, then who are we?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks