Life in the frozen north: Trauma and healing in a remote Canadian town

Canada’s indigenous First Nations have suffered generations of dislocation and discrimination. In the opening part of her new series, Rachel Savage, the first winner of The Independent’s Rupert Cornwell prize for foreign journalism, meets the families trying to break the cycle step by step

Jimmy Peter Einish was in a police cell more than 300 miles from home when he realised he needed to take control of his life. Trapped in a dark spiral of drinking and violence, he was locked up in Sept-Îles, a port on the north shore of the mighty St Lawrence River in the Canadian province of Quebec, for getting involved in a fight. “Something just clicked inside of me,” he remembers. “I just said ‘What am I doing to myself?’”

That was in the late 1980s. But it wasn’t until 1998 that Mr Einish finally overcame his addiction to alcohol. Since then, he has counselled dozens of others on the often long road to sobriety in Kawawachikamach, an indigenous community in northern Quebec only accessible by all-day train or a return flight costing C$1300 (£760).

Mr Einish’s story is, like those of so many other indigenous Canadians, the story of a struggle to overcome the poverty, dislocation and abuse caused by nearly two centuries of colonisation and discriminatory government policy. Yet, it is also a story of hope, of a community beginning to shape its own destiny.

Jimmy Peter Einish was born in 1960 in Lac-John, a native reservation a few miles outside the small mining town of Schefferville. Schefferville was carved out of the wilderness in 1954 by the Iron Ore Company of Canada, for the workers who toiled in the open pit mines nearby. While the white workers had spacious modern houses, Mr Einish remembers his family of 14 living in two rooms, with no electricity or running water.

Before his father was able to buy a skidoo in the mid-1960s, firewood had to be hauled to the house. In winter, temperatures could drop below -50C. “Floors were really cold at night,” Mr Einish recalls, cradling his baby granddaughter in broad, scarred arms at the kitchen table of his warm but haphazard family home.

As indigenous groups such as Mr Einish’s Naskapi were corralled into reservations by the Canadian government in the mid-20th century, alcohol began to tear through communities, following the path razed by other European diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis. For as long as Mr Einish can remember (and he admits his memories may have blurred over the decades), his parents drank. And with the drinking came domestic abuse, as Mr Einish’s father passed on the violence he had received at the hands of his own father to his wife.

“The worst incident that I can remember was my father hitting my mother in the head with firewood,” Mr Einish says. “And there was blood all over the floor. And my elder brother was really … yelling. He ran towards my mom and he slipped on her blood and fell on the floor.”

“Just watching my mom laying there I thought, she’s gone,” he continues. “I can’t remember how, how they got her to the hospital. But she survived.”

Despite the hardship he endured in Lac-John, Mr Einish remembers his early childhood with some nostalgia. Whereas most of his community are now obese, Naskapis in the 1960s were kept lean through the hard work of carrying wood and water, and a traditional diet of caribou and fish. “It was so good, so good,” he says wistfully, remembering a dish of boiled caribou with oats, lard and pepper.

Those memories are somewhat rose-coloured, perhaps, because of what came next. Mr Einish was one of around 150,000 indigenous Canadian children forcibly taken from their families to attend Indian Residential Schools between the mid-19th century and the 1990s. The schools, whose number peaked in the mid-1960s, aimed to assimilate the children into white society. To “kill the Indian in the child”, as then prime minister Stephen Harper admitted in an official government apology in 2008.

Mr Einish remembers being forbidden from speaking his native Naskapi language when he was taken south in 1970. He did not see his parents for four years. “They kept telling us, ‘You’re going home soon to visit your parents,’” he says. “They kept saying that to us.”

Despite the separation, Mr Einish remembers his first couple of years away from home being relatively benign. But then he was transferred to another institution, with two of his siblings. “[It] was the worst,” he recalls. “A lot of abuse. Physical abuse. There was also sexual abuse. It was a horrible, horrible place.”

“We saw one guy jumping out of the window on the fifth floor,” he says, his voice flat. “He was in flames. He’d burned himself.”

On his return from residential school, aged 14, Mr Einish was angry. He took up drinking, dropped out of the local school, which, like the schools down south, meted out corporal punishment, and picked fights with white people.

We saw one guy jumping out of the window on the fifth floor. He was in flames. He’d burned himself

“This is the way, I thought, to fight white society, because of what they did to us,” he says. “I had to have some kind of a war and get revenge.”

Mr Einish was battling his own demons, though – and heaping fuel on the fire as he did so. It was a battle that took him more than a decade to recognise, in a jail far from home, and another decade to win.

Meanwhile, the wider war in communities like Kawawachikamach, built as a new reservation for the Naskapis in 1984, nine miles northeast of Schefferville, and known locally as Kawawa, continues. In 2010 60 per cent of First Nations children on reservations were living in poverty, more than three times the Canadian average, and an increase of 4 per cent from 2005. Aboriginal women are almost three times more likely than non-native women to experience violence. Indigenous youth suicide rates are more than five times the national norm. But, while trauma is continuing to be passed down through the generations, many indigenous Canadians are trying to break the cycle.

* * *

The day begins bitterly. A flurry of snowflakes gusts from a leaden sky. Two sturdy off-road vehicles ferry a group of nine walkers (myself among them) down a dark dirt track that winds between banks of snow and small, narrow pine trees. A few miles in, Rita Tooma, a slight young woman sitting in the front of the car, starts to cry. Jessica Mitchell, who runs Kawawa’s wellbeing programmes, puts an arm around her as she drives. Country music plays on the radio. “Hurry up and get walking!” one of the hosts exhorts in Naskapi. The car bursts out laughing.

After posing for group photos, we turn back to walk the way we just came. Three young men bound off and are quickly lost over the horizon. Twelve-year-old Jayla climbs back into a vehicle after a couple of miles. Having persuaded her mother, Jennifer Sandy, to participate in the walk, she claims her boots are too painful to walk in.

Ms Sandy and I fall into step. A few days earlier she had seen her doctor, who advised her to exercise and eat better if she wanted to avoid diabetes. She explains she gave up smoking eight months ago and is using the $5,400 estimated annual savings to take her two youngest children on holiday in the Caribbean. But the cigarettes were replaced by fizzy drinks, of which she had been drinking five to six cans every day.

No more, says Ms Sandy, who works in ticketing and logistics for Air Inuit, the sole airline that flies from Schefferville. She has started wearing a pedometer and is planning to attend the crossfit classes, a form of circuit training, the local police chief William Moffat runs most weeknights. Groceries are around 30 per cent more expensive than in Sept-Îles, and not all Naskapi families can hunt and fish to catch healthier “country food”. Yet Ms Sandy argues, “there is no excuse” not to eat more healthily.

Naskapis have struggled with the transition from a nomadic existence following the caribou across northern Canada, their health yet another casualty of colonisation. Three-quarters of patients at Kawawa’s clinic were obese in the year to April 2017, according to the annual report of the community’s governing body, known as a band council. Rates of high blood pressure and diabetes were both 30 per cent. Previously unheard-of diseases like cancer are now killing elders.

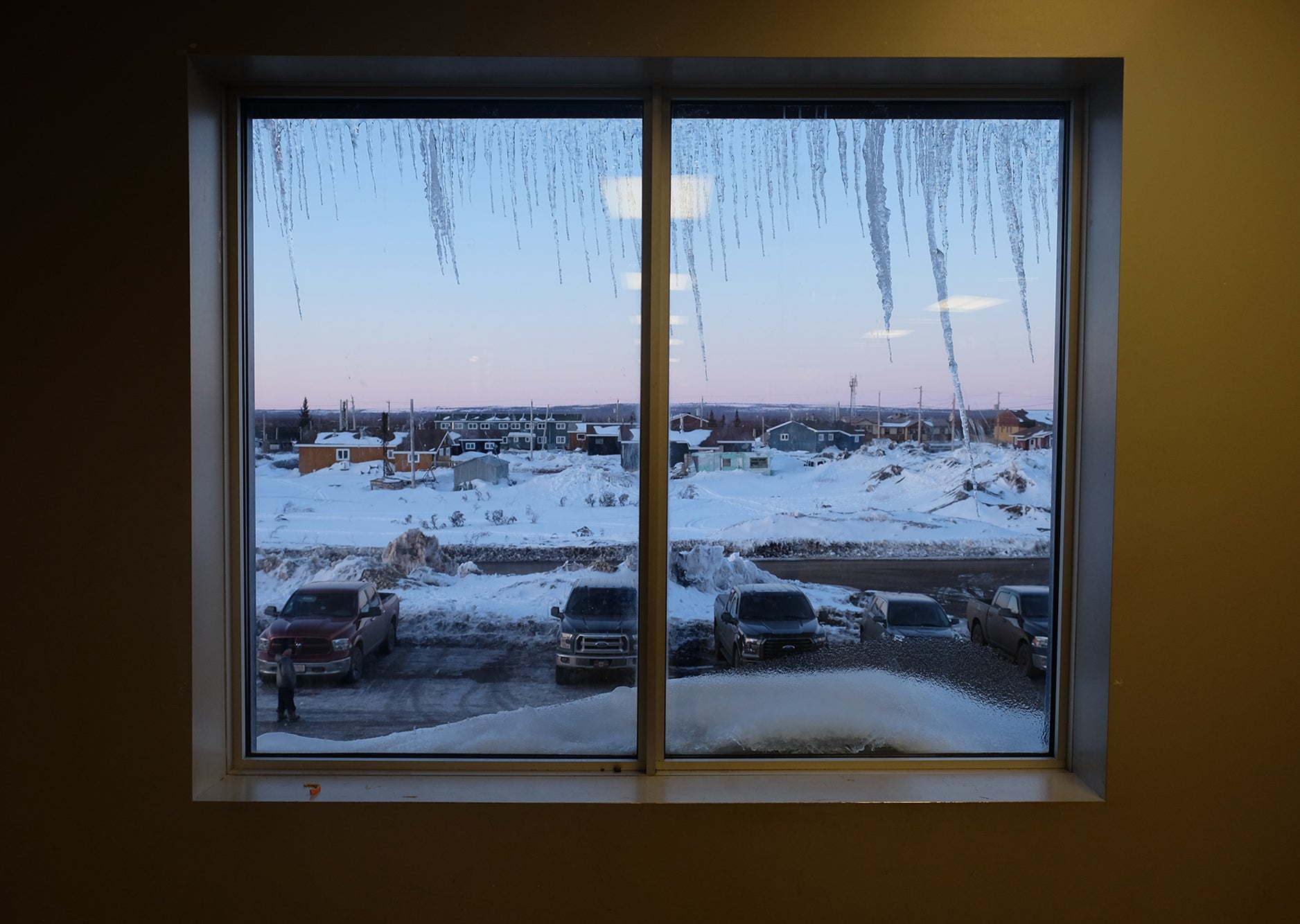

Kawawa had a population of 906 in March 2017 and another 450 Naskapis live outside the community. The centre is a jumble of municipal buildings, none higher than a few stories. Identical wood-clad houses spread down a gentle slope towards a lake that is frozen most of the year, and alongside the dirt road towards Schefferville. Most families have at least one sturdy pickup truck or 4x4 that they use to travel the short distance “to town”, or the even shorter distances around the community, along with skidoos and quad bikes.

But Naskapis are becoming more active. As well as crossfit sessions, there are volleyball and fitness classes in the school gym and ice hockey tournaments in a new arena, which opened in March 2017.

An ice hockey training programme for children run by Joé Juneau, a former Canadian national team player, ran for a pilot season from October to May this year. If it continues next year, as Mr Juneau and community leaders say they want it to, it will provide opportunities for the best young players to travel across Quebec for competitions. Mr Juneau also wants ice hockey to be used as a carrot to keep children in school as only a handful graduate from high school in Kawawa each year.

Exercise has other benefits. It serves as a distraction, temporarily at least, for people of all ages who may otherwise spend time drinking or taking drugs. Some health workers think the abuse of speed is on the rise in Kawawa, although there is no data. Everyone, from the elderly to gaggles of teenagers and excitable children, gathers at the arena to watch their friends and relatives play in tournaments. Many in the community also believe the increase in exercise is helping mental health, a belief that is backed up, although not conclusively, by an increasing number of studies.

* * *

As we get further along the “healing walk”, Ms Sandy talks about the difficult decision to split up with the father of her two youngest children four years ago, who she says was verbally abusive. About how traditional healing led her to vomit up “the evil and the bad stuff” from her past. How she worries for her 22-year-old unemployed son, who is “into drugs and alcohol” despite her own relative sobriety.

“It’s his choice,” she says. “But he didn’t see that growing up. Alcohol is just not my thing.”

“My mum drank,” she explains. “I still have the fear of being woken up in the middle of the night to fighting.”

Ms Sandy is picked up by a car after around seven miles, forced to stop by a sore knee. The sun has come out and the dirt track shines, muddy with melted ice. I walk the last hour or so with Rita Tooma and Susan Shecanapish, a quiet middle-aged woman wearing a black beanie with white words reading: “Waskaikinis Healing Walk 2017 / In Memory of Jimmy & Job”. We stop at a two-metre-high white cross, at whose base nestles a small statue of Jesus in a perspex-fronted, black-roofed box.

Ms Tooma wades through the deep snow towards it, chattering happily in Naskapi. The shrine is for her brother Jacob, who died aged 21 in a skidoo accident. Ms Tooma, now 23, was just six years old when it happened. “I lost my son too,” says Ms Shecanapnish.

We continue down the dirt road, the walk as much therapy for me as it is for the others. A couple of days earlier, a week into my trip, a friend, someone I had lived with for a short while, had died suddenly. Everyone I tell about Pete is sympathetic. But the shock, the rawness, is compounded by the feeling that I am in exactly the wrong place at the wrong time, a place so remote it is too complicated and expensive to go straight back to the UK.

I stay for another eight days. And, through a lens of grief, the struggles that so many of the people I interview have experienced become clearer.

* * *

It can seem, sometimes, as if trauma is everywhere in Kawawa. The alcoholism. The abuse. The shotgun that misfired. The young man that froze to death on the railway tracks after a night out.

Something just clicked inside of me. I just said, ‘What am I doing to myself?’

Police were called to 67 attempted suicides in the 12 months to April 2016; one person succeeded in taking their own life. The number of attempts fell to 57 the following year and to 36 this year, says William Moffat, the police chief, who runs the crossfit classes partly to help himself and his officers cope with the strain of trying to save people.

Suicidal tendencies within a community can fluctuate, though, as the effects of past trauma and ongoing challenges ebb and flow. Police were called to 19 suicide attempts in 2015, for example.

Kawawa is like a person taking three steps forward and two and three-quarter steps back, says Marcel Lortie, the interim executive director of the reservation’s clinic, who is on his fourth stint in the community since 1986.

The Naskapis’ challenges are being made harder still by a housing crisis. Myna Mameanskum struggles to remember how many of her four children and nine grandchildren are living in her three bedroom home. Her daughter Esther had to move in after mould in her flat threatened the health of her baby; Esther’s husband is living with his mother and their five children move between the two houses. Ms Mameanskum’s son Patrick lives in the basement with two children. Daughter Alexandra is about to give birth to her first child when we speak in April.

Ms Mameanskum’s third daughter, Charlene, is forced to live in Quebec City with her two children as she cannot get a house in Kawawa.

“Summertime… it’s going to be nice, I’m going to sleep in the truck,” she says. “I don’t care, as long as my grandkids are sleeping good.”

“I wouldn’t mind sleeping at my work,” says Ms Mameanskum, who works at Kawawa’s child daycare centre. “I don’t mind, but I can’t.”

This is the way, I thought, to fight white society, because of what they did to us. I had to have some kind of a war and get revenge

The band council receives 30 to 40 applications for the two or three houses it builds every year. The majority of the reservation’s 170 housing units have problems with damp and mould, says James Pien, the head of Kawawa’s department of public works, which builds and maintains the houses. Meanwhile, a high birth rate – in 2017 more than 55 per cent of the population was under the age of 30 – means overcrowding is only growing worse.

After a referendum in December 2014, the council switched from a first-come, first-served system for allocating houses, which had sometimes meant single people getting houses at the expense of large families, to a points-based system. Mr Pien admits the methodology is still imperfect. He notes that a colleague with one 15-year-old daughter is still without a house of his own.

“I’ve been working in housing for the past 10 years and it’s one of the most stressful jobs in the community,” he says. “To address everything is basically impossible.”

Mr Pien blames what he believes is an active policy of neglect by Canada’s federal government. Kawawa has been able to access specific funds to build a raft of new buildings, from the ice hockey arena to a clinic and a soon-to-open women’s shelter. But extra money to build more houses, which Mr Pien estimates would reach $45m, has been elusive.

Inevitably in such a small, isolated community, tempers and relationships have frayed. “It’s a piece of crap,” says Ms Mameanskum of the council’s protestations that they are trying to be fair in allocating new homes. “All they do is give to their families.”

Vote-hungry council members are also to blame, she alleges, for not forcing enough people to pay the $50 weekly rent. Ms Mameanskum says she pays hers, as well as her daughter’s $90 weekly rent in Quebec City.

The first claim is untrue, says Mr Pien. But rent is a problem, the council admits. Its total rental arrears were $3.4m at the end of March 2017, according to its annual report, with more 53 households owing more than $25,000. Less than half of the $360,000 rent owed was collected in the previous year. But even making up that shortfall would only pay for one extra house to be built every year, estimates the council.

In February, the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau promised $1.5bn over the next decade to address a crisis that is prevalent across Canada’s reservations, where almost a fifth of indigenous Canadians live in houses without enough bedrooms.That was on top of another $1bn promised in 2016 and 2017.

But that probably won’t be enough. By one estimate as much as $30bn is needed to fix the infrastructure deficit – not just houses, but water, sanitation, schools, roads – on reservations.

“Indigenous peoples in Canada are more likely to experience poor housing conditions and overcrowding than the general population,” says Martine Stevens, a spokesperson for Indigenous Services Canada. “We realise much work needs to be done and investments like those mentioned above are just a first step.”

Kawawa is a community that is making progress, though, however slow and uneven. Many Naskapis, of all ages, have given up alcohol and others have never touched a drop. A fast fibre internet cable is being laid next to the railway tracks from Sept-Îles this summer. The dusty road to Schefferville should be paved in the next couple of years. There doesn’t seem to be a week without a community event, from the sports tournaments and healing walks to a “walking-out ceremony” that commemorates children’s first steps. When grief does hit, Naskapis rally round to support one another.

Jimmy Peter Einish is almost preternaturally calm. You would never know that he had been a violent alcoholic, were it not for his frankness about his past. “I’m not a miracle worker,” he says of his work counselling people dealing with addiction and loss.

“[When] I lost my father, mother and last brother… it reminded me of an elders’ saying, to honour them,” he says. “Not to fight it, but to honour them.”

“When I realised that my life turned around.”

Read part two of ‘Life in the Frozen North’ next Sunday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments