The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Succession, spying and selling up: is this the end of the Barclay brothers’ empire?

With a debt that could run into hundreds of millions, the family company in receivership and the likely forced sale of their Telegraph newspapers, Chris Blackhurst charts the extraordinary unravelling of the Barclay brothers’ world

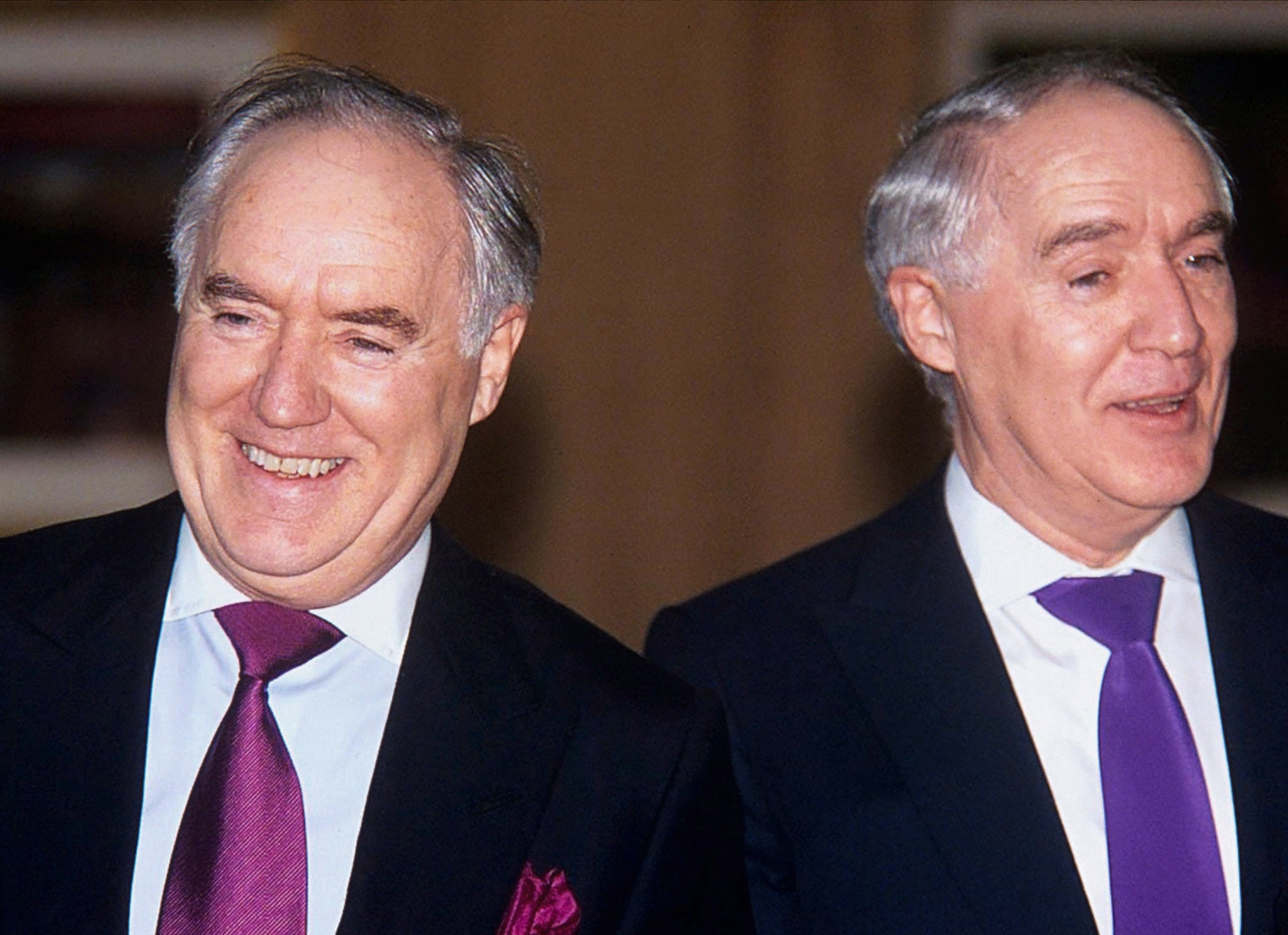

Occasionally in London in the 1980s and 1990s, it was possible to catch a glimpse of the Barclay twins, David and Frederick. They would be sitting at a discreet, rear corner table in one of the luxury hotels they owned – the modern Howard near Temple, or latterly the Ritz.

They wore matching pinstripe suits to go with their identical looks. They were born 10 minutes apart, first Frederick, then David in 1934. The only way to tell who was who was the side they parted their hair – Frederick was left handed with a right-hand parting, David right handed with a left-hand parting. If they were not spotted in one of their hotels, they could frequently be seen having a morning coffee on Avenue de Grande Bretagne in Monaco where they shared a residence. Again, they would be tucked away at the back of the cafe.

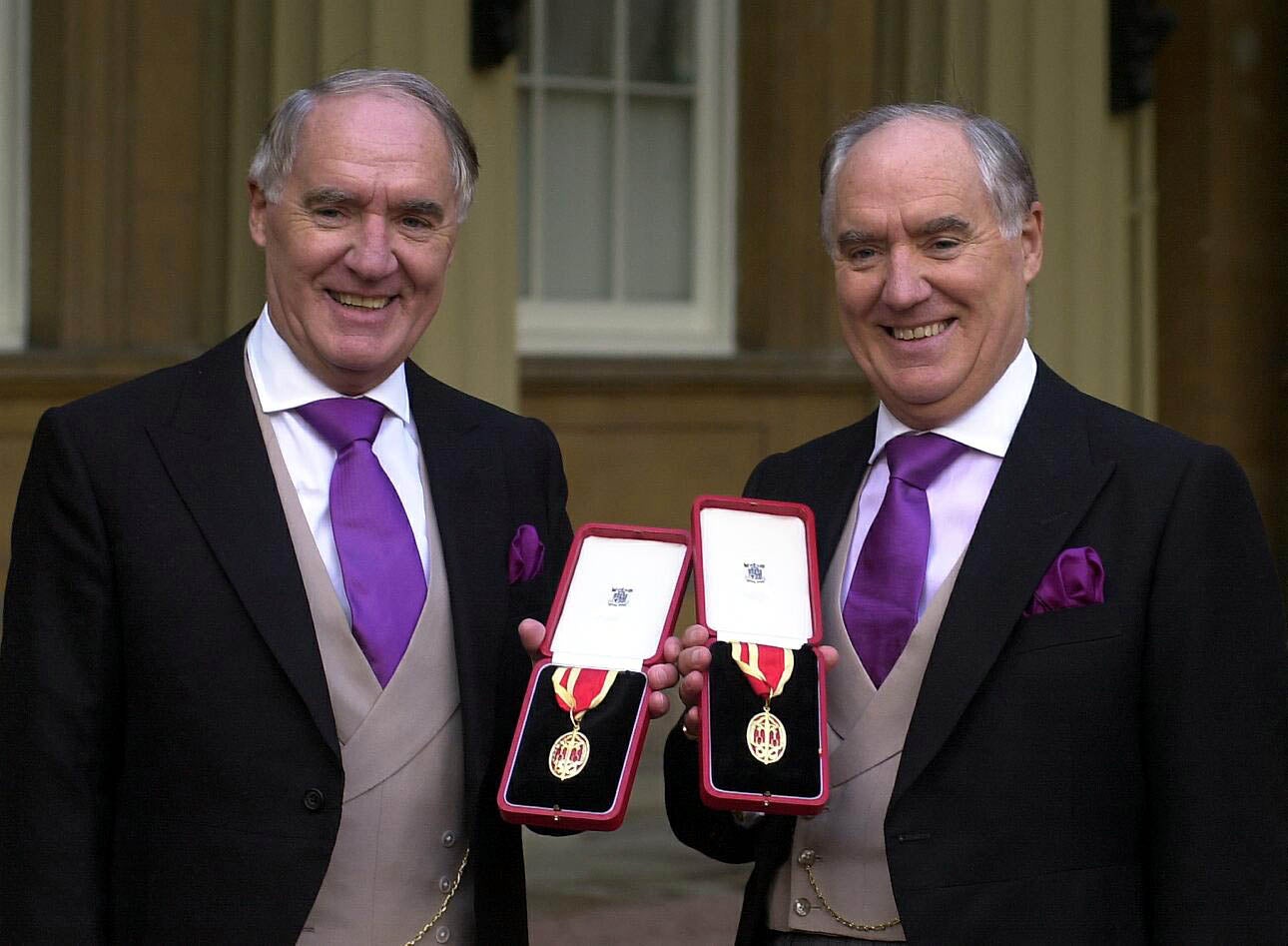

They were seemingly inseparable. Married with families of their own, but a firm double-act. They both had a passion for ballroom dancing, but rarely were they photographed. An exception was when they were knighted in a “double-dubbing” in 2000 for their support of medical research.

They were famous for taking their privacy to extraordinary lengths, buying the lease of Brecqhou, near Sark in the Channel Islands, and building a 60-room gothic fortress for them both on the tiny island. It was heavily guarded and uninvited visitors were always warned off.

Yet, for all their secrecy, the investments they made were often well-known: hotels, store chains, newspapers and magazines, breweries, shipping lines, casinos, car dealers. This year’s Sunday Times Rich List puts the fortune of Sir Frederick and the Barclay family (Sir David died in 2021) at £6.4bn.

Which is why the receivership of the family company, Bermuda-based B.UK, prompting the likely forced sale of their Daily and Sunday Telegraph newspapers and The Spectator and Apollo magazines, is so extraordinary.

Officially, Lloyds Banking Group is owed £65m, but reports suggest the debt could run to hundreds of millions of pounds. The money has not been repaid, so Lloyds has foreclosed. B.UK owns Press Acquisitions, the parent company of the Telegraph titles and The Spectator and Apollo, the art journal. The publications would command around £500m, possibly more if an auction ensued and they were viewed as “trophy” assets.

The papers and magazines are said to be performing well at present. Having been through a difficult patch when sales and advertising fell and it struggled to make online pay, the Telegraph is thought to be doing much better. The Spectator, meanwhile, has been going from strength to strength of late.

The problems reside elsewhere, as a Barclays spokesperson, keen to stress they do not impact the publishing arm, emphasises: “The loans in question are related to the family’s overarching ownership structure of its media assets. They do not, in any way, affect the operations or financial stability of Telegraph Media Group.”

Even so, you could be forgiven for supposing the Lloyds cash was relatively minor in the order of things, such has been the extent of the Barclay portfolio now and down the years. Surely, they could afford to repay?

Apparently not. Theirs is a family that is asset rich but cash poor. The group’s assets are held in a myriad of trusts and settlements. It’s a byzantine structure, much of it in secretive offshore havens, constructed to reduce tax to a minimum. The money is there but not accessible. Apart from the newspapers and magazines, what’s left is no longer humming: mostly Yodel, the courier service, and Very, the online retailer.

To make matters worse, the Barclays have ceased to function as a single unit for a while. Where once the twins were together, their successors seem completely split.

Despite the opaque nature of the family’s arrangements, the veil has been raised several times recently, suggesting faction-fighting of the sort that would do Succession proud. Indeed, while the TV drama appeared to be based loosely on the Murdochs, the feuding Barclay relations may have proved more inspiring.

In February 2020, a newspaper was tipped off to go and look at a gravestone in southwest London. Under a birch tree in Mortlake cemetery, an old headstone had been replaced with a new one. It was for Frederick Hugh Barclay, a travelling salesman who died in 1947 from respiratory problems caused by being gassed in the First World War. Frederick had eight children, including the twins, David and Frederick. The black granite memorial carried the citation “In loving memory of our father” but mentioned only two of them, David and Andrew. Of the other six, there was no reference. Some family members were said to have never agreed to the new stone and were “deeply hurt”. It was the public sign of a private schism.

Another was the hearing in the London High Court, also in 2020, of a lawsuit brought by Sir Frederick and his daughter Amanda against Aidan, Howard and Alistair, three of Sir David’s children, Andrew Barclay, Aidan’s son, and Philip Peters, an aide to that side of the family. Incredibly, Sir Frederick and Amanda accused them of bugging their conversations while they sat together in the conservatory of the Ritz, a secluded spot where father and daughter liked to chat while Sir Frederick indulged in a cigar.

It was true. More than 1,000 conversations were secretly recorded over several months. The taping only came to light when CCTV filmed Alistair handling the bug. On inspection, a second recording device was uncovered. The bugging case was eventually settled.

At the heart of this remarkable divide was the decision taken by the twins on board their Lady Beatrice luxury yacht – named after their mother – some years ago for them to step back and to split the empire four ways, between David’s three children and Frederick’s one.

Until then it was 50/50 between David and Frederick. Now, Amanda has a 25 per cent share but is unable to block whatever the three wanted. Frederick has said he bitterly regrets the move, “the greatest mistake I’ve ever made”.

Sure enough, David’s children subsequently wished to sell the Ritz, but for a sum far below what Frederick and Amanda thought the hotel was worth. Whenever they tried to raise concerns, they found themselves outmanoeuvered and second-guessed – the result of being bugged. For their part, Sir David’s branch insisted no formal offers at the Fredrick and Amanda valuation were ever received.

Relations deteriorated to such an extent that the once bonded-at-the-hip pair came to blows. Frederick’s ex-wife Lady Hiroko took him to court over non-payment of £100m from their divorce settlement. She told the court how she had witnessed the twins coming to blows aboard the yacht. “They were punching each other,” she said.

Frederick dug his heels in over the payment, saying he could not pay. Hiroko did not believe him, arguing: “It is not that he cannot pay, but that he will not pay.”

Several hearings have reached the point where Frederick faces the real prospect of jail if he does not cough up. Last month, Aidan told the High Court that his 88-year-old uncle’s financial and marital difficulties were “not good for the family”. While Aidan felt “terribly sorry” for what had happened to his uncle and aunt, he said it was “not really my issue”.

Frederick had been ordered to pay the £100m; Hiroko, who petitioned for divorce on grounds of unreasonable behaviour, said he had not and was in contempt of court. The judge ruled that Frederick was in contempt, but for failing to pay £245,000 he owed her in legal fees and maintenance.

The judge was told that he could not find the money because his nephews “hold the purse strings”. Day-to-day responsibility for “group business” was theirs. Frederick said that a trust which could provide him with the money was being “starved” of “funds from the family business” and told the judge his nephews had “turned off the tap” in 2019 as a result of “conflict”.

Aidan admitted that business was “not easy”. Added Aidan: “It is a time of doom and gloom, yes. It is not actually easy at the moment. We have had severe pressures in the last couple of years.”

Presumably, he was referring to Yodel and Very and other assorted businesses, and not the newspapers and magazines. Lloyds wants its money back and is moving against the whole publishing group. In theory, there is substantial wealth, but it’s locked up in trusts and settlements held by each of the four children.

A fortune that was amassed and controlled two ways – effectively one-way, such was their inseparability – is now divided into four. The Lloyds loan appears to have fallen through the crack, with no one able or willing to settle it.

Such a state of affairs would have been unthinkable once but then, as we saw on Succession, once the founder generation moves on, things can quickly unravel. No one is saying the Barclays are poor, but we could be witnessing the dissolution of a once great empire.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks