2021 and the race to save the world

Why are some experts upbeat despite the litany of ‘catastrophic failures’ to curb – let alone reverse – the demise of the natural world? Kate Hughes finds out

Chaos. That’s the word that comes to mind – and that’s not just about the rise in incidents of extreme weather. The year has left confusion, anxiety and division in its environmental wake, with those of us on the ground without the relevant PhDs trying desperately to navigate the marketing spin, greenwashing, photo ops and weaponised slogans.

In the meantime, the bombardment of doomsday data continues. The Arctic Ocean is getting warmer decades faster than expected, Brazil’s Amazon rainforest is now a net carbon emitter pumping out a fifth more CO2 through record levels of burning and tree removal than it is absorbing. Global warming, according to the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, shows we’re closing in on the 2015 Paris Agreement’s 1.5C ceiling desperately fast, with temperatures already 1.239C warmer than they were in 1880.

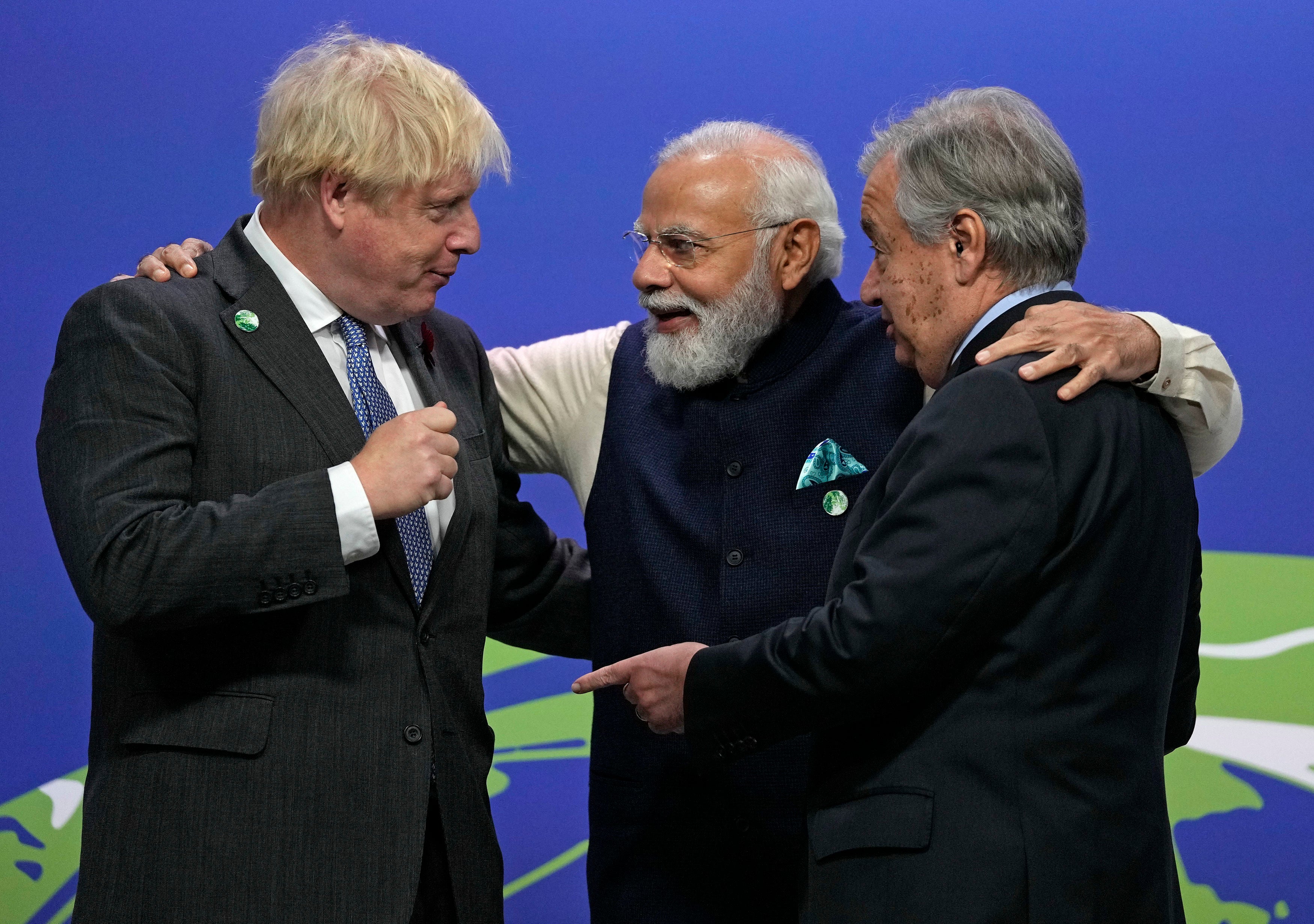

Even when the most powerful people in the world congregated in one room, the existential threat didn’t seem enough to produce a commitment to change.

Cop26 president Alok Sharma fought back tears as he said he was ‘deeply sorry’ over the outcome of the negotiations

At November’s UN Climate Change conference, better known as Cop26, where fossil fuel lobbyists (of the variety recently caught on camera boasting about derailing climate change legislation in the US) outnumbered national representatives, the world’s major emitters conspired to water down the agreed wording around fossil fuel divestment from “phasing out” to “phasing down” at the 11th hour.

Days earlier, the showstopper opening pledge to end deforestation had frayed within hours as key nations rapidly backpedalled using various semantics. India had finally agreed to net zero during the conference, but only by 2070 – 20 years after the global deadline of 2050, and a date so distant that critics say it makes the pledge meaningless.

The current emissions pledge from China means the world’s biggest polluter – whose president Xi Jinping, along with his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin, didn’t even turn up – won’t hit peak emissions until 2030.

There was also the small matter of money. Developed nations whose own economic strength has been built on polluting and habitat-depleting activities for centuries had to be strongly reminded of their promise to deliver $100bn (£75bn) of climate finance every year to poorer nations. It should have started in 2020. It is now not promised until 2023. Conference president Alok Sharma fought back the tears as he said he was “deeply sorry” over the outcome of the negotiations.

Days later, US president Joe Biden’s rousing rhetoric appeared forgotten as his administration set about auctioning off drilling permits across 1.7 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico to the highest bidders from the fossil fuel industry.

Green and pleasant land

Here in the UK, the government that hosted Cop seemed to spend most of the year hell-bent on incarcerating climate activists, including British Paralympic gold medal winner James Brown, and passing legislation through parliament that will criminalise those engaged in peaceful protest under rules that are, arguably, contrary to the convention on human rights. In direct response to climate change activism, the amendments to the bill are becoming more extreme with each stage of the parliamentary process.

While that rumbles on, plans are still afoot for the deep coal mine at Whitehaven – the first for 30 years. Advocates point to job opportunities, but campaigners and even the government’s own climate change committee warn the project will derail the UK’s carbon reduction pledges by adding 8.4 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere every year. After a last-minute intervention, it still hangs in the balance. That, and the policing bill, will receive final verdicts early next year.

All the while, the UK is “nowhere near” meeting the emissions targets locked in at the Glasgow summit. The Climate Change Committee, the independent public body, says it may, in theory, be possible to limit the UK’s contribution to just under 2C – higher than the 1.5C nations had agreed in Paris to ward off the worst of the effects of climate change.

Institutional investors continue to flood the global economy with money for fossil fuel expansion that simply can’t happen if we’re to stay within 1.5C.

“The UK’s five biggest banks provided £227bn in fossil fuel finance between 2016 and 2020,” notes Anna Pick, the media and policy officer at research and campaign group Positive Money. “That’s despite International Energy Agency warnings that investment in new oil, gas and coal supply must stop this year if the world is to reach net zero by 2050.”

There were some chinks of light – not least the decision to pause the proposed Cambo oil field off Shetland after Shell pulled out because the figures didn’t stack up – but from the outside looking in, they seem like isolated life rafts in a dark and turbulent sea. News that the amount of plastic litter found on Britain’s beaches has hit a 20-year low, or that some plants are now sucking up more CO2 in response to human activity provides little solace when globally, we’re heading for 2.4C of warming, even with the Cop26 pledges.

The future is now

To be clear, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that exceeding 1.5C of warming will pass crucial tipping points and extremes of temperature that will place significantly more of the global population in physical danger. And around the world, 2021 certainly gave us a taste of that.

With global warming currently at around half that projected peak, this year saw cyclones kill 150 people in Indonesia and East Timor, hurricanes kill 45 people in the US, heatwaves kill 569 people in British Columbia, and flooding killed 170 people in western Germany during the worst natural disaster in Germany and Belgium for decades.

Texas saw a deep freeze of -13C, China experienced its worst sandstorm in a decade stretching from Mongolia to Hubei province near Beijing, wildfires raged through southern Europe, scorching 235,000 acres in Turkey alone, and Greece sweltered in 47C.

In September, Biden revealed natural disasters in 2021 alone would cost the US economy £100bn. “We have to make the investments that are going to slow our contributions to climate change, today, not tomorrow,” the US president said. Two months later, his administration was busy with those drilling permits.

Thanks to the increasingly worrying evidence from climate scientists, countries’ plans now include stronger targets

So why are words like “hopeful”, occasionally even “optimistic” coming out of the mouths of experts across a range of environmental specialisms as they reflect on the events of the past year? For starters, Cop26 wasn’t an unmitigated disaster.

“In the run-up, many countries published updated plans to reach the target of the Paris Agreement to hold ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels’,” says Colin Nolden, a research fellow in energy and climate governance at the University of Bristol.

“Thanks to the increasingly worrying evidence from climate scientists, most of these so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) now include stronger targets. The UK’s NDC (the net zero strategy) sets out how the government intends to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This is significant progress in terms of both ambition and plans to actually reduce emissions.”

Independent European think tank E3G, which focuses on the political economy of climate change, describes a monumental shift to conclusively “end international public finance for coal and the beginning of the end of international public finance for oil and gas”.

“The participation of energy financing heavyweights, including the G20’s largest fossil financier Canada, as well as the US, the UK, Spain and Germany, is a historic step forward, creating pulling power for ending public fossil fuel finance.”

In another session, the finalisation of the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 rulebook was another significant outcome of Cop26, though its legal and technical nature meant it didn’t get quite the same media attention as other deals. Put simply, Article 6 enables countries to trade certified reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. “This agreement thereby allows countries to team up to trade and exchange such mitigation outcomes to increase their emission reduction ambitions,” Nolden explains.

Germany, for example, has expressed an interest in creating a climate alliance to increase emission reduction ambitions as part of its upcoming G7 presidency. Elsewhere, 100 countries used Cop26 to agree to cut methane production – a gas between 28 and 80 times more heat-trapping than CO2 – by 30 per cent by 2030.

Follow the money

This year, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a club led by former Bank of England governor Mark Carney that claims to have reached 450 firms, representing 40 per cent of global assets, committed to cutting the emissions from its lending and investing to zero by 2050. Demand for environmental, social and governance-focused investments continues to skyrocket on the ground, too, particularly in the UK, where such funds saw record net inflows of £1.5bn in November, according to funds network Calastone.

Asking nicely doesn’t work while fossil fuels remain profitable. We need our public institutions to impose hard restrictions on new investment

Despite a pre-Cop Budget that made no reference to climate change, the chancellor used the conference to announce that from 2023, large businesses in high-emitting sectors will be required to publish plans for getting to net zero. This follows Treasury plans to make large businesses disclose their exposures to risky fossil fuel investments from April 2022.

Meanwhile, in the run-up to Glasgow, the government had also launched two sets of green gilts (government bonds), raising £16bn for environmentally friendly projects and attracting a total of £170bn in bids from investors.

“Twenty twenty-one has been a big year for green finance, and we’ve seen some progress, as climate campaigners have raised the alarm on banks, insurers and pension funds funding climate destruction,” says Pick.

“But the government is leaving it up to bankers and CEOs to lead the transition, which is why we’re seeing a lot of hot air and voluntary pledges, but not nearly enough concrete action to shift financial flows away from dirty sectors and towards green ones.

“Asking nicely doesn’t work while fossil fuels remain profitable: to stop new oil, gas and coal expansion this year as the IEA has called for, we need our public institutions to impose hard restrictions on new fossil fuel investment.

“There’s also a big clean finance gap to fill, and the government must be prepared to spend much more – at least £30bn a year – to shape the green sectors of the future.”

Help for habitat

Too often, though, the focus has ignored the other half of the equation – habitat and biodiversity. And here, too, experts report cautious optimism. As long as we can unpick a traditionally siloed mentality among government departments. When the Environment Act was added to the statute book in November, Tony Juniper, the chair of Natural England, described it as the most groundbreaking piece of environmental legislation in many years.

“For the first time, this Act will set clear statutory targets for the recovery of the natural world in four priority areas: air quality, biodiversity, water and waste, and includes an important new target to reverse the decline in species abundance by the end of 2030,” he said.

Things are moving in the right direction. But we need billions to turn this around – now, not in 10 years

“It sets in law new tools that Natural England and others can use to help meet those targets, which will, at last, enable us to lift the grim graphs of species decline upward towards a nature-positive 2030.”

Alastair Driver, a director of Rewilding Britain, also points to the new £640m nature for climate fund, with its focus on addressing biodiversity loss and promoting habitat regeneration. Announced in May, it was part of the response to the ground-breaking Dasgupta review, the crucial piece of work that highlighted the fundamental role played by natural capital – the natural assets that underpin every human activity, from clean water to breathable air and food.

“Things are moving in the right direction,” Driver says. “But we need billions to turn this around – now, not in 10 years.”

The revamp of farming subsidies and support following Brexit will be crucial too. When the details are confirmed, the environmental land management schemes, known as Elms, will reward environmentally focused land management through sustainable farming incentives, local nature recovery and landscape recovery.

The new plans will replace the existing basic payment scheme and countryside stewardship programme, and trials of the schemes are now underway.

“This is a great chance to move forward and represents a significant ramping up of efforts and funding. But we need to make sure Elms reverses the decline [in habitat],” warns Driver. “Without an equal split of the funding [between the three schemes], we will still be going backwards.”

Lightbulb moment

But while he focuses on the state of British biodiversity, Driver also echoes a wider sentiment: that 2021 was the year that humanity took a basic but critical step forward in the race to save the world. We have finally, collectively, acknowledged the natural world is facing an existential threat because of human action. Gone are the stymying days of questioning whether climate change is even happening or why.

We’re seeing a massive step change whereas before we were just fiddling around the edges of the issue

Suddenly we are all sitting up and taking notice, and that notice is sustained. Research by the University of Bath this year showed that not only is climate change now a top priority among the UK public, for example, but that prioritisation never wavered – even at the height of the pandemic.

“I have never seen a time like this for acceptance from those in government,” Driver adds. “There is clearly much more recognition of the climate and biodiversity crisis and that those two things are inextricably linked.

“I’m enjoying the best time in my career convincing leaders, and we’re certainly moving faster than we have in the past. We’re now seeing a massive step change whereas before we were just fiddling around the edges of the issue,” he says.

“The fact that climate change was on every front page around the world for two weeks solid shows the influence Cop26 has had this year,” says Austin Whitman, CEO of the US-based non-profit Climate Neutral, which channels corporate money into renewable energy programmes. “The Cop deal included the first-ever mention in conference history of fossil fuels. While it took 26 meetings, it’s a victory to celebrate nonetheless. Once you have that, you get to fix it,” he says.

Whitman points to large-scale, high-profile changes in the movement of capital and policies prohibiting the financing of fossil fuels at one end of the awareness spectrum and the number of personal friends who are quitting their careers to help drive the fight against climate change at the other.

We’re seeing the first wave of a systemic change. It’s 20 years too late, but it is more systemic. I’m optimistic

“Companies are expanding the footprint of their sustainability from the fringes of their operations,” he says. “We’re seeing the first wave of a systemic change. It’s 20 years too late, but it is more systemic. I’m optimistic.”

Far too often, though, we have patted ourselves on the back for merely starting to scale back the rate of decline in 2021, when we should be paying down the debt of over-consumption, abuse and exploitation.

The responsibility for that doesn’t stop with the leaders of great nations. While global summits full of weakened words have fuelled real and deeply felt anger, fear and frustration among those of us left on the pavement outside, the tacit consensus remains that, for the most part, we should all be able to carry on as before. Perhaps just with a hybrid car or a reusable cup. This is simply not the case.

So now, as we look to 2022, the battle to save the world – at every level of society, influence and power – boils down to two words.

“More” and “faster”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks