The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Meet Mrs Beeton, the original tradwife (and the most radical of them all)

In its heyday, ‘Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management’ was only outsold by the Bible. More than 160 years later, novelist Josie Lloyd reckons her cooking, cleaning, shopping and wellbeing tips are more relevant than ever

There are many things that can get you addicted to TikTok, but the trend of domestic influencers donning their prettiest dresses to bake cakes has mesmerised a generation. Whether it is the 23-year-old mum of three Nara Aziza Smith whose 10 million followers are addicted to her every move in the kitchen or tradwife Hannah Neeleman, the mother of eight who goes by the name @ballerinafarm and has built up a following of 10 million by documenting her life as a homemaker on her Utah farm, these content creators have never been so popular or as controversial.

But who started our obsession with seeing what goes on behind the kitchen door? There was early TV personality, chef and author Julia Child in the Sixties, who unleashed French cuisine on the American public and was one of the first to persuade TV executives there was an audience for cooking programmes; then Delia Smith was credited with skilling up a generation of homecooks in the Seventies and Eighties and has since passed on the domestic goddess mantle to Nigella Lawson who brought us her signature style of putting the kitsch into the kitchen.

But, arguably, it was long before them that the first real influencer in the domestic sphere made a difference to millions of women across the globe – and who made traditional homecraft into a radical act.

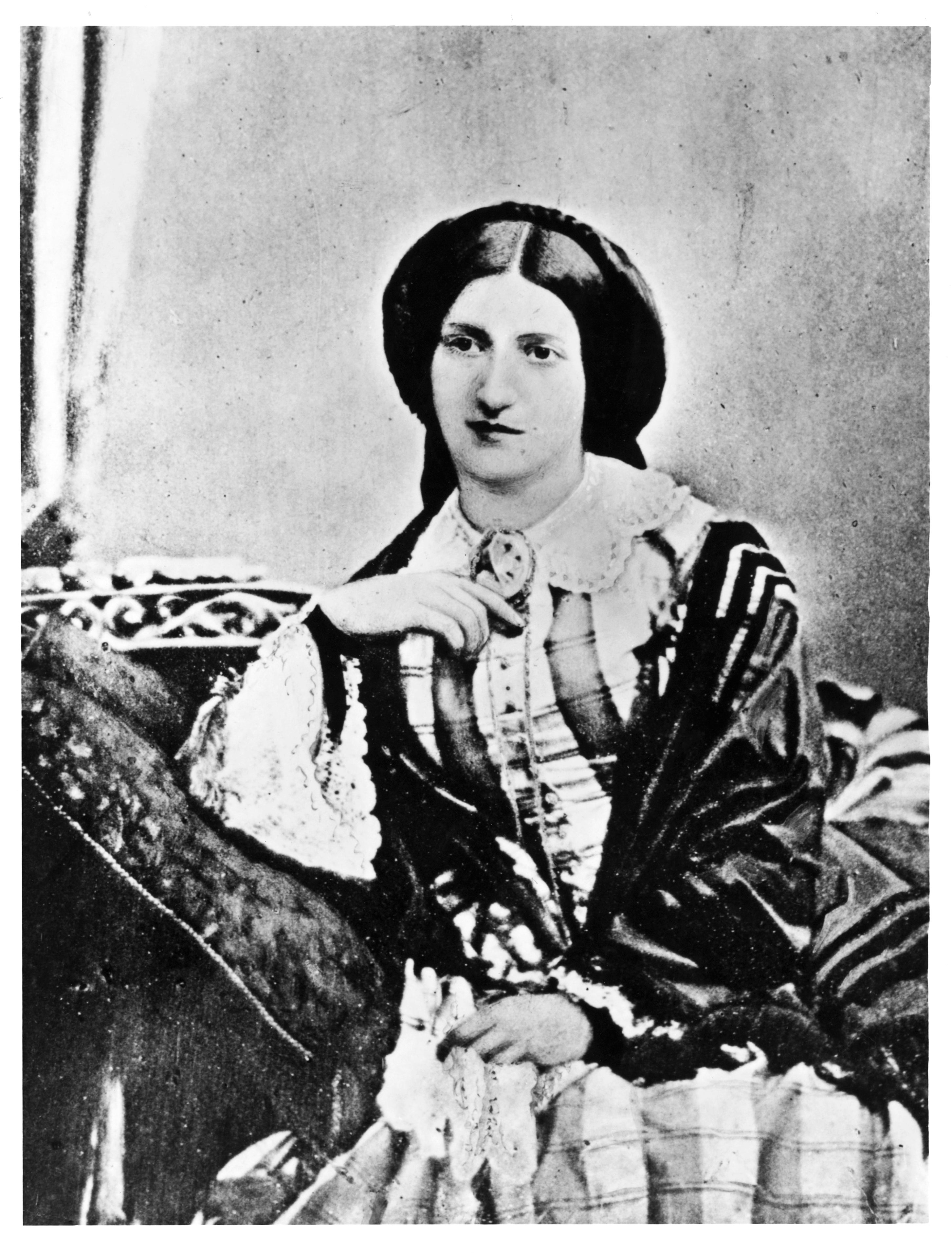

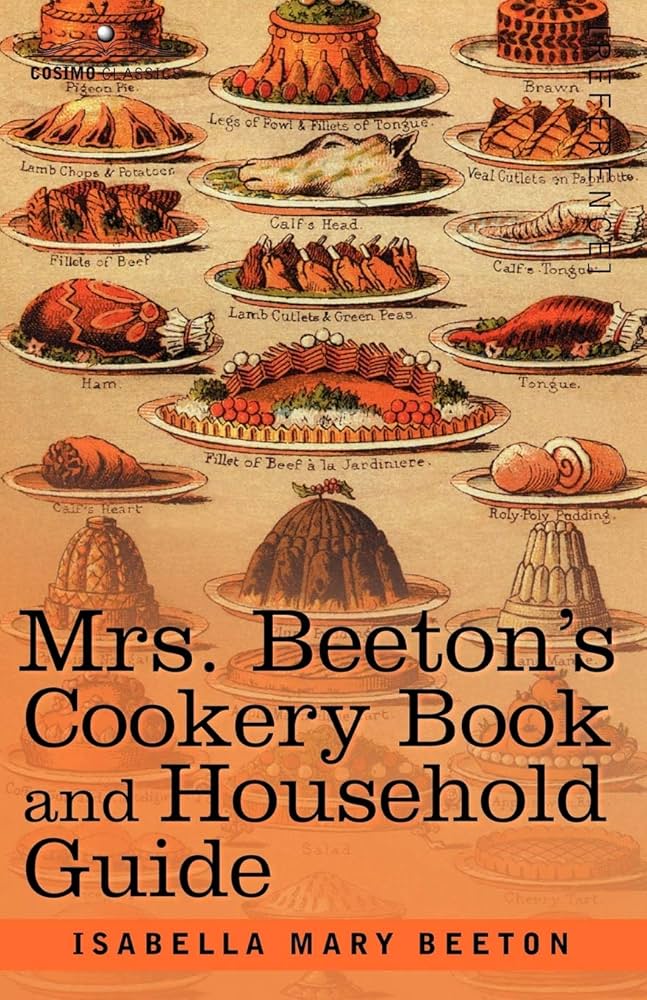

Her name was Isabella Beeton and her tome The Book Of Household Management made her an icon of the Victorian age. The cookbook, first published in 1861, was also a how-to manual, described by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as having “more wisdom per square inch than any book ever written by a man”.

Beeton, born in London in 1836, was the eldest of three daughters. Her own mother had remarried a man who had four children and went on to have another 13 with him – Beeton was frequently the caretaker of this brood of siblings that she often referred to as “a living cargo of children”.

It was probably this formative experience that taught her how to manage a household and to economically feed many hungry mouths around the dinner table. After a brief stint being educated in Germany, she married Samuel Orchart Beeton, an ambitious publisher and magazine editor.

At a time when most women stayed at home, Beeton worked closely with him on The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, translating French fiction and penning the cookery column. But a pressing need was becoming apparent. She told her readers: “What moved me in the first instance, to attempt a work like this, was the discomfort and suffering that I had seen brought upon men and women by domestic household management.”

With the booming economy of the time, the newly formed middle classes were setting up homes in the neat new suburbs. Husbands became commuters and many women found themselves alone, far from traditional family support and in charge of running a household, raising children and managing domestic staff. They were expected to know how to pick a housemaid, entertain the boss and his wife, order coal and spot a dodgy fishmonger and they didn’t have a clue how to do it.

In stepped Mrs Beeton with her common sense and clear advice on absolutely everything they might encounter in the domestic sphere. She set out an orderly plan with rules to follow to keep the ship afloat. But although her name became in her lifetime – and posthumously – a byword for domestic order, Beeton herself was a radical pioneer of her day.

Far from being a traditional wife, she commuted to the office, not stopping work, even when her first son, Samuel, died aged just three months. She went on to suffer another two miscarriages, until her next son – also Samuel – was born in 1959.

With a full-time job, she had very little time to cook and there’s little evidence to suggest she enjoyed it when she did. Instead, she collected recipes from the readers of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine as well as borrowing from all the cookery writers of the day.

But what was genius – and earned her legions of fans – was that for the first time she listed the ingredients, then “a plain statement of the mode of preparation” and a careful estimate of cost and the numbers the recipe would feed and when it was seasonable.

Until then, recipes were rather rambling French ones or had a complicated method first. The clarity of detail that we take for granted in recipes today was largely thanks to Mrs Beeton’s insistence on there being little room for error. And, while she was accused of plagiarism, the staple recipes she collected in her famous tome are ones we know and love today – from carrot soup to bubble and squeak, pork pies and Victoria sponge.

I came across my grandmother’s copy of The Book of Household Management when I was clearing out my mother’s cookbooks. Flicking through the family heirloom, I was astonished to discover that Beeton’s advice to her Victorian readers holds up today. In fact, you could say, she suggested it first.

For example, she was a great advocate of getting up an hour earlier than the rest of the household and taking a cold bath to get invigorated and into the right headset for the day ahead. Advice that will feel familiar to anyone who followed the “just one thing” suggestions from the late Michael Mosley.

She also encouraged women to budget properly, stating that “frugality and economy are home virtues” and no matter how much you had, those who managed a little well, were most likely to succeed in the management of larger matters. A recent banking app I downloaded recently said almost the same thing.

She gave people the confidence to haggle for the best quality for the lowest price, teaching them to keep a daily diary of what was paid and balance the books every month. Her food philosophy was to cook seasonally and thought it prudent to cook a large joint of meat on Sunday, then repurpose the leftovers into economical meals throughout the week. Nothing went to waste and she advocated making bone broth and stock as the basis of casseroles and soups.

While she probably didn’t have the scientific information we now have about the microbiome, she seemed to know what was good for people. Her common-sense instructions of eating plenty of fruit and fresh vegetables, regular meals and the importance of a good night’s sleep chime with the newest wellbeing advice.

As far as fashion went, she chose comfort, knowing that fads came and went and could quickly look ridiculous. When buying new articles of “wearing apparel”, she advised that “the mistress considered three things: 1. That it not be too expensive for her purse. 2. That its colour harmonises with her complexion, and its size and pattern with her figure. 3. That its tint allowed its being worn with the other garments she possesses.” As the world turns against fast fashion, these three rules seem more relevant than ever.

She also considered domestic labour as work that should be respected and laid out clear instructions for hiring – and more importantly – retaining decent staff. Recognising that running a household was a gargantuan task, she has a “you-can-do-it” tone, giving the mistress of the house the highest status possible. “As with the commander of an army, or the leader of any enterprise, so is it with the mistress of the house.”

Despite his wife’s success, however, Samuel made some disastrous business decisions and in 1862, Beeton had to leave her comfortable home in Pinner and move in above the offices. Suffering in the grim London air, her son died at the age of three. Her next son, Orchart was born in 1863 and the young family moved to Kent.

After a trip to Paris in 1864, Beeton was working on an abridged version of her book, but pregnant again, she went into premature labour. Her daughter was born, but Beeton died eight days later of puerperal fever. She was just 28 years old. Several biographers have suggested that her husband unknowingly contracted syphilis in a pre-marital liaison with a prostitute and passed it on to his wife.

Samuel sold the rights to The Book Of Household Management after her death and never got to benefit from the fact that for over a century, it became the must-have English cookbook, outselling every book but the Bible.

Feeling that Beeton would chime with today’s vogue for the intricacies of domestic life, I decided to revive her spirit for my latest novel Miss Beeton’s Murder Agency. Introducing Alice Beeton, a fictionally distant relative of Beeton, she runs the Good Household Management Agency, placing high-end staff in London mansions and sprawling country piles and, like her forebear, insists on things being in their proper order – even when it comes to murder. A magpie when it comes to recipes, Alice bakes several of Mrs Beeton’s recipes during the course of the book and they’re reproduced in the text.

It’s good to know I’m doing my bit to bring Beeton back, because her legacy shouldn’t be forgotten. As Nicola Humble in her history of British food sums it up: “In her lively, progressive way, she helped many women to overcome the loneliness of marriage and gave the family the importance it deserved. In the climate of the time, she was brave, strong-minded and a tireless champion of sisters everywhere.”

I can’t help feeling that if she were alive today, Isabella Beeton might well be a domestic influencer herself, championing homemakers, child-raisers and amateur cooks everywhere. Because she knew what the modern influencers do too – that it’s really not as simple as it looks.

‘Miss Beeton’s Murder Agency: The gripping new cosy crime mystery detective novel by Josie Lloyd’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks