Homeless should be given period products for free by shelters and charities, say campaigners

Lack of products and facilities can lead to poor hygiene and risk of illness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sanitary period products should be more widely accessible to cash-strapped homeless people who are sleeping rough or in shelters as they often have to go without, say campaigners.

Periods can be difficult. Severe cramps and complications can debilitate sufferers from living their everyday lives, hormonal fluctuations can cause mood swings and there is always the worry about having enough supplies and available toilets nearby.

But there are women, and transgender people, who have it much more difficult than the average when living on the streets or in homeless shelters – as condoms are given out without charge but sanitary products are, currently, not as freely available.

The lack of pads, tampons and cups, and private wash facilities – due to having to rely on public toilets – can make the lives of menstruating homeless women stressful and humiliating.

Unpredictable and unsafe situations can mean that those who are on their periods could go several days without changing their form of protection, which can lead to infections or potentially fatal illnesses such as Toxic Shock Syndrome.

The problem is then compounded by not being able to freely do things other people take for granted such as being able to launder garments and replace damaged clothes and sheets.

A campaign was started by Sarah Bakharty, Oliver Frost and Josie Shedden – who met as interns at a London advertising agency. They set up a petition calling for hygiene products to be made free, that now only needs less than 6,000 signatures to reach its 50,000 goal.

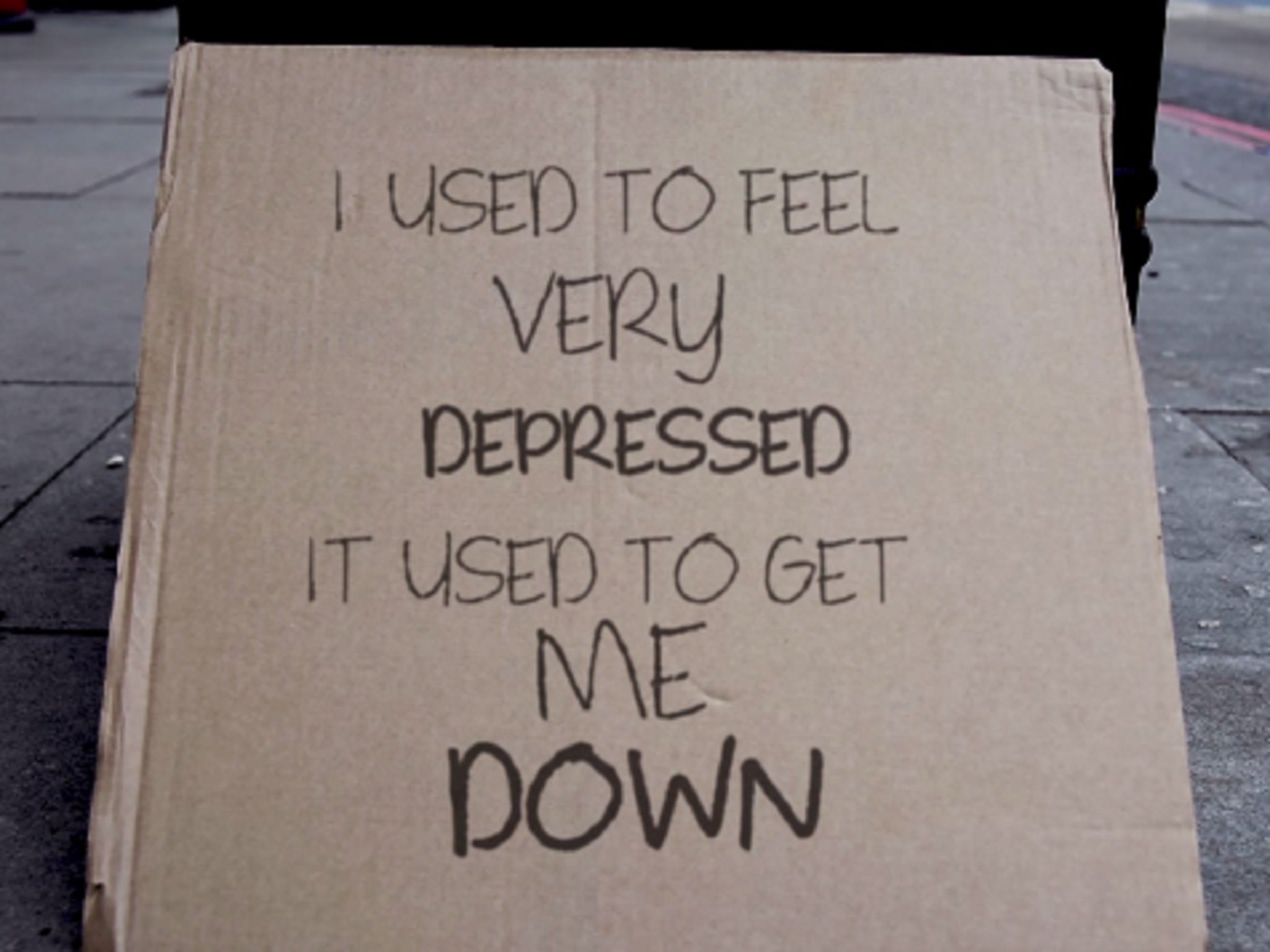

The trio interviewed a woman who was sleeping rough in Brixton for six months, who goes by the name of Patricia. She said having her period while homeless made her feel down and depressed.

She told Bakharty: “I used to end up going in the public toilets and, especially when there weren’t no places where you could get sanitary towels, I end up taking a cloth or whatever, ripping it up like, you know, and then just using that.

“I used to feel very depressed. It used to get me down. Why does a woman have to rip up a cloth, and put it between her, to protect herself from bleeding?”

Another woman, who goes by the name of Zoe, told Vice News earlier this year that she even had to resort to shoplifting sanitary products or asking former school friends if they had any spare when she met them while begging.

If she could not get hold of any, she had to rely on using tissues.

Patricia added: “If everybody could donate sanitary towels, then a woman would be happy, wouldn’t they?”

Around 12 per cent of rough sleepers in London are women, however the total number for any town and city is likely to be higher due to “hidden homelessness”, according to data provided by Crisis.

And with an average of 60 period days per year – based on five days a month – the lack of assistance during that time of the month is not a temporary or minor problem.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments