Periods: the menstruation taboo that won't go away

A five per cent tax has been placed on sanitary products. Why don't we consider them essential items for women?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I told male friends that I was writing about periods, they changed the subject. Some more enlightened guys tried to engage with the idea and then confessed they didn’t actually know much about periods as it’s not something that happens to them, and then changed the subject. But when I told female friends and colleagues, they became animated. “My husband doesn’t want to have sex when I’m on my period” was a common comment, and another friend said she was embarrassed when her boyfriend saw where she kept her sanitary products, but the general feeling was that periods are a taboo, even among women, and that we should learn to speak more openly about them.

It’s interesting that so much embarrassment, awkwardness, and shame surround a natural bodily function experienced by half the population at some point in their lives. We don’t hide toilet paper away, yet some women still get flustered if a tampon drops out of their handbag, or we might buy a floral-patterned tin to hide our sanitary pads. If you spotted some toilet roll tucked away and covered in a little bespoke baggy in someone’s loo, wouldn’t you find it faintly ridiculous? And yet that’s what we do all the time with sanitary products, as though the evidence that we have periods is something to be ashamed of.

The most recent example of prejudice towards periods occurred just a few weeks ago: a five per cent tax has been put on sanitary products, because they are considered luxuries (women have the option to use reusable cups, which aren’t taxed) but men’s disposable razors are not taxed even though they are also a luxury and also add to landfill.

The prevailing attitude that periods are icky is something that Chella Quint, a menstruation education researcher, is fighting. She has tried to combat some of the negativity around periods with a magazine entitled Adventures in Menstruating. “Yeah, periods can be a pain in the uterus, but sometimes it's nice, and sometimes it's simply no big deal,” she says. She’s also created a project to help us see periods in less of a negative light, called the #periodpositive project. She says it’s important to teach girls to see that there’s nothing shameful about menstruation. “If you menstruate, having regular periods is a vital sign, like your heart rate or your blood pressure, that shows your body is working well,” she says.

In her feminist novel How to be a Woman, Caitlin Moran writes that periods are viewed as something disgusting simply because they belong to women: “[We live] in a culture where nearly everything female is still seen as squeam-inducing, and/or weak – menstruation, menopause…” But period prejudice goes way back.

Historically, periods have been revered and reviled in turns. But mostly just reviled. We were off to a good start with the ancient Greeks, who may have used menstrual blood in medicine and also as a fertiliser (it’s rich in nitrogen). Hippocrates believed that menstruation cured women of pre-menstrual tension and was very pro-bloodletting in general. So far so inoffensive.

Sometime around AD 77-79, Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History about the effect a period has on a woman: “Her very look, even, will dim the brightness of mirrors, blunt the edge of steel, and take away the polish from ivory. A swarm of bees, if looked upon by her, will die immediately,” he writes.

This might seem ludicrous now, but this idea of women being ritually unclean is seen in the bible. The Old Testament states that anyone who touches a woman on her period will be “unclean until evening”, and Bishop Theodore of Canterbury (690 AD) took this one step further and forbade menstruating women from even visiting church.

Dominique Christina, a self-proclaimed womanist and slam poet (who appears in this amazing video) says religion has a lot to answer for where period prejudice is concerned.

“There is a culture of shaming around women's bodies particularly as it relates to menses,” she wrote to me in an email. “I sat in Sunday School listening to stories about how corrupt the world was and that the catalyst for evil was a woman. That this woman, for her sin, was ‘cursed’ with blood. Now, as a little girl, that is an incredibly stigmatising picture of woman. For me it was like, oh great, so my body is evidence of God's punishment? I am the accursed one? I come with a borrowed rib and the 'imposition' of blood because God was displeased. And apparently I was also [an] evil temptress who contributed to the ‘fall of man’. Gotcha. There is no daylight in that constructed narrative for women.”

In 1995, when the journalist Karen Houppert wrote an article on the tampon industry for Village Voice, the accompanying image caused a furore. The picture showed the lower half of a woman’s naked body with one leg hitched up – nothing new there, as nearly nude women are used in advertising all the time – but there was a discreet but unmistakable string of a tampon showing just under her thigh. There was no blood to be seen, not a thread of pubic hair, certainly no vagina on show, simply a string. This was enough. Houppert went on to write a book, The curse: confronting the last unmentionable taboo: menstruation, which challenged "the culture of concealment". When the photographer Robin Holland, was questioned about the image later, she said, “People were horrified… People are perfectly happy to see women as sex objects, but the actual biology of our bodies is apparently gross and unmentionable.”

In her book The Woman in the Body, the anthropologist Emily Martin argues that the reason for this disdain for periods is that “menstruation not only carries with it the connotation of a productive system that has failed to produce, it also carries the idea of production gone awry,” and that periods are evidence the body is “making products of no use, not to specification, unsalable, wasted, scrap.” But that doesn’t seem to completely solve the puzzle. A period is also a sign that the body has the capability to make life, that everything is in good working order, that a woman is fertile.

“Blood is a siren,” says Dominique Christina. “When we see it we think it is alerting us to a wound, a malady… something is wrong if we see blood. But menses is a part of the machinery of my body. I cannot allow anyone or anything to position me to feel flawed or poorly made. No. Men are not conditioned to regard their own physiology as a liability. Whose agenda does it serve for me to regard myself from that place?”

Dr Valerie Curtis, Director of the Hygiene Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and author of Don't Look, Don't Touch: the science behind revulsion has found that part of the reason people are uncomfortable with the idea of periods is we all have an evolutionary disgust of blood and other bodily fluids. The revulsion response is not totally specific, she points out, so we sometimes see things as a threat even if they aren’t.

“If it’s inside you it’s fine, if it’s on your finger it’s okay but if it’s outside of your body, for example if you find a plaster on the floor, that’s disgusting, because you’re identifying that it might not be your blood,” she says. “That’s the same for menstrual blood, when it’s inside it’s OK, but when it’s outside, say on a tampon or pad, you become wary.”

Periods, she explains, come from a risky area, hygienically speaking:“it comes out from a breeding space for germs.” Admittedly, it can get icky down there.

But the attitude towards periods seems to go above and beyond a basic innate dislike of blood. In fact people have tried to prove that menstrual blood isn’t the same as normal blood at all. A study at Harvard University in the 1950s was devoted to finding out whether menotoxin, a poison suspected to be exclusively present in menstrual blood, existed. George and Olive Smith, specialists in diseases of the reproductive organs, injected little animals with menstrual blood and when they died, they took it as proof of poison in the blood, even though Bernard Zondek, a gynecologist (who, incidentally also developed the first reliable pregnancy test in 1928) had disproved it. When he mixed antibiotics with the blood and the animals didn’t die, thus showing it was bacteria that killed the cute-and-fluffies, not the innate evilness of womankind. Phew. What is the most astounding about this is that the Smiths felt the need to disprove the presence of menotoxin in the first place.

“Is there a certain fear from males about this mystical female function? I don’t have evidence for that,” says Curtis, “but there’s definitely something above and beyond the natural fear of blood.” There are cultural-specific “sequestration rituals”, she notes, around menstruating women. In Italy, women aren’t meant to make pasta sauce if they’re at that time of the month. In Nepal, women have to sleep in a cattle shed overnight and they aren’t allowed to cook when they’re on their period, so for four days a month the man will take over the cooking. “Until very recently in the UK people believed that dough wouldn’t rise if a woman tried to make bread while menstruating,” she adds.

Curtis is currently trying to help encourage people in Nepal to wash their hands after going to the loo and before preparing food. They don’t believe it’s necessary, except when a menstruating woman is involved.

Kat Lazo, who runs TheeKatsMeoww You Tube channel, also speaks about the portrayal of periods in the media, arguing that men make jokes on film and TV about something that they don’t experience, “and that’s why they’re so inaccurate,” she says.

“Majority of media are made by men,” she tells me, “and like most things, men are misrepresenting periods. Men are writing about and depicting periods from a third-person point of view; an uneducated one at that. Periods are either a comedic punchline or a horror show. Theres a huge stigma associated with periods, and men are only perpetuating it.”

She cites Movie 43 and Superbad, where a girl starts bleeding and the boys see it and freak out, as just two examples of a girl being the butt of the joke.

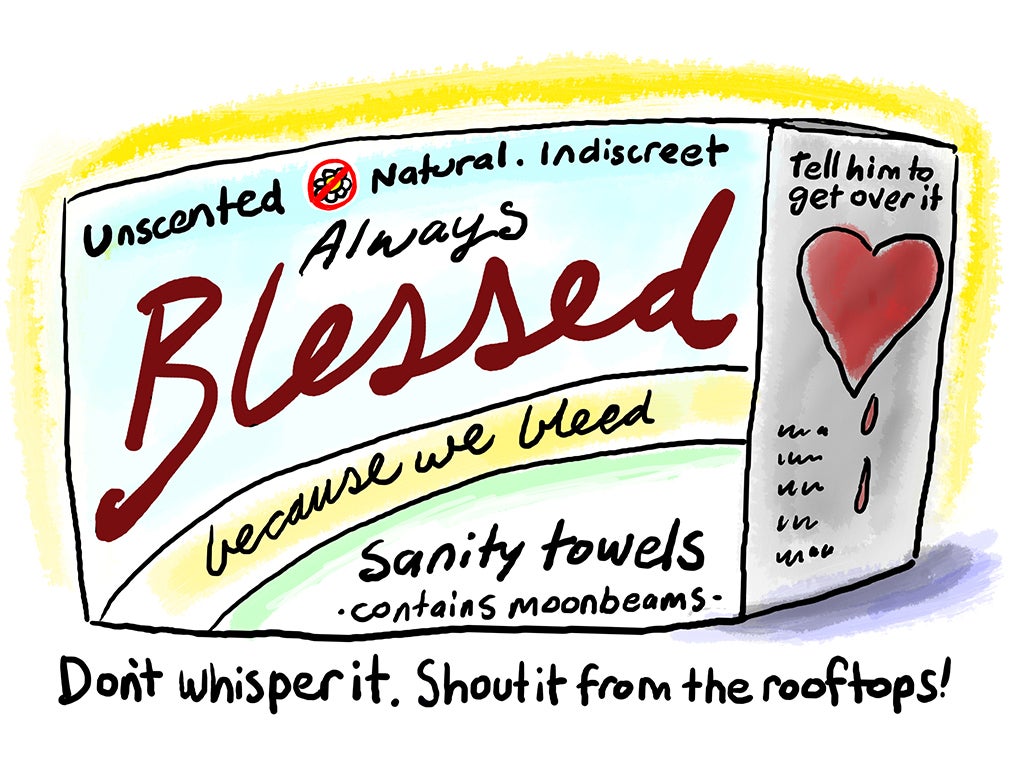

Following the publication of her magazine (which she discusses in her TED talk, here), the writer Chella Quint received angry messages. She believes this is a result of a history of stigma and a language of shame. Advertising has exacerbated the problem, she says. “Many ads still use the words 'whisper' and 'secret' and 'discreet' and create ambiguous packaging — words and tactics that have been used for over 80 years to imply that periods shouldn't be discussed,” she says.

Incidentally, the first commercial sanitary towel, introduced in 1896 by Johnson & Johnson, failed to sell, not because there wasn’t demand for the product but because advertising for sanitary products was thought improper and so no one even knew they existed.

Even now, more than a century on, every time you buy sanitary product you are greeted by the message that there’s something wrong with your body, Christina points out. “When you go to the grocery store or the market, there are whole aisles dedicated to making vaginas smell like spring flowers. On some level that felt misogynistic to me. Like vaginas needed to be fixed, particularly when they are bleeding. That sparks ire for me.”

And to add insult to injury, you’ll now be taxed on that product (read more about the petition to stop the tax here). If that’s got you feeling angry, take heed: our periods are what set us apart, but they are also what unites us. The word bless comes from the old English, blēdan (“to bleed”). So bleeding is a blessing, not a curse, it’s a sign we can give life. And not all menstrual myths are so negative. In “The Period Poem”, Dominique Christina comments on how women who spend time in each other’s company can, some have suggested, synchronise their menstrual cycles – they bleed together. “Hold on to that,” she says, “there’s a metaphor in it.”

If you’ve been made to feel uncomfortable because of your period, please tweet me about it with the #periodprejudice hashtag. To learn how you can address #periodprejudice, look at Chella Quint’s #periodpositive hashtag for everyday things we can all do.

For more information on periods visit here, and if you suffer from heavy periods learn more about what you can do here

This article was originally published on 5 August 2014. It has since been republished

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments