Zoe Adjonyoh: the African food myth, Ghana's healthy diet and being self-taught

Can food be a way for people to connect with each other and their own cultural heritage?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Zoe Adjonyoh calls it the “last continent of relatively unexplored food in the mainstream domain”. One of its best-kept secrets is Ghanaian food – or at least was until she came along.

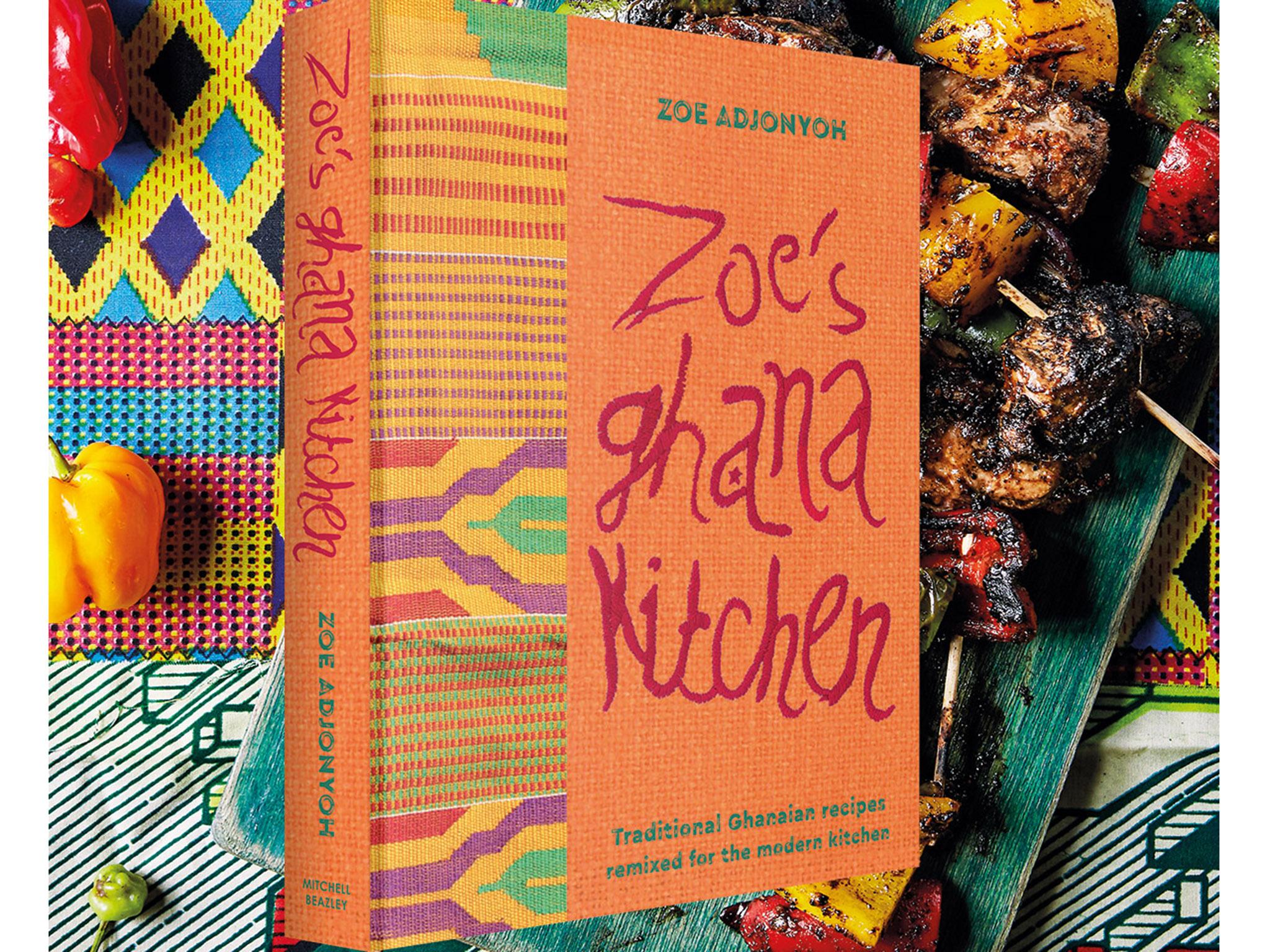

Adjonyoh is credited with changing the narrative of African cooking with her cookbook, Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen. Published in April, it’s been the talk of town. Actually she’s been speaking out about Ghanaian food for the past seven years – and it’s more poignant now than ever, as this year marks the 60th anniversary of Ghana’s independence from British rule.

After leaving Ghana as a child, Adjonyoh has lived in London. She moved to Hackney Wick in the east of the capital in 2010 – only to find that the area lacked the sort of places she likes to eat in.

Armed with her Baby Belling cooker and a wallpapering table, she served up her famed peanut butter stew for a selection of friends in what became her first pop-up. The following year, during the Hackney Wicked art festival, her living room became a makeshift restaurant. “We were so inundated with hundreds of people over the few days who wanted to book and eat my food, so I collected email addresses from people to start supper clubs,” she says.

“It was a strange phenomenon. I never expected it to be so well-received or so many people to want to book dinner in my living room. So then we started writing down all the things it could be, from a cookbook to sauces. It was all a bit fanatical really.”

After realising this could be a viable business, Adjonyoh says she was quite determined to change how people perceived the different countries of Africa and the food people eat. “There was a time in the Eighties when the media coverage of Africa was of starving children with bloated bellies, and people thinking ‘why can’t they pay for themselves’. It was such a negative image for me when I was growing up and I wanted to dispel that. There’s so much art, literature and food there. And for me, food was my access point.”

She compares it to a time in the Sixties when Indian food gained traction because of the popularity Indian cookbooks. Then a flurry of curry houses began lining the high streets and the British obsession with the food has shown no abating since. “Now Indian people and Indian food are no longer seen as ‘other’. It’s broken down otherness and barriers. Food is a great leveller.”

Food from Africa had largely been marginalised for a number of reasons, Adjonyoh says. “First-generation of Africans in the UK cooked for themselves in their own community, and there was no notion that anyone else would be interested in it.”

These were also hole-in-the-wall places, not contemporary dining spaces. “So even if you were interested in trying it, there wasn’t a space you might feel comfortable trying it in.”

But how times have moved on. Following on from her successful supper clubs and residencies, Adjonyoh gained a permanent residence at Pop Brixton, the food court made from shipping containers in south London. For her, it was a perfect setting: a collection of small and independent businesses on an unused space that gave back to the community. After hearing about the idea, she applied – a day before the deadline – and earned a coveted place.

It’s only got six tables and is up a short flight of metal steps but it’s all rather fitting as it’s based on a Ghanaian chop bar – West African slang for a roadside eatery. Inside cutlery pots are painted with the coloured stripes of the Ghanaian flag with the slogan, “It’s Ghana be tasty”; side benches with upholstered African prints also store takeaway containers and the shelves are made from an old pub sign. The tiny space is well used and it’s always busy, continually turning over tables and dishing out takeaways for those who can’t squeeze in.

Adjonyoh describes her food as a celebration of Ghanaian ingredients and flavours. “I’m trying to get people to use these ingredients in new ways and interpret them in the new ways. Recipes need to evolve to recapture people’s attention.”

Her most popular dish is the jollof spice fried chicken. After seeing it served up, I quickly changed my order. It’s got a great kick to it and a beautiful coating of crunchy buttermilk and tender chicken underneath. The menu also has an allergen key, where even gluten and vegan are considered. But it’s not just playing to western fads as Ghanaian cuisine is changing too. It’s becoming more health conscious Adjonyoh says, as most countries are. In 2013 there was a government scheme to get people to use less palm oil. But the diet generally is “super healthy”, says Adjonyoh, as little is processed.

She thinks we’re now in the middle of a West African food revolution thanks to the amount of pop-ups, restaurants and food markets opening. But when she started, she was the first West African supper club in London. “I didn’t have a role model,” she says. “But lots of people who came to my supper club have now started up their own.”

Adjonyoh didn’t even have anyone teach her to cook, and she’s never had any professional training. In fact, the closest she came to working in the food industry was selling sandwiches at her student union. She wasn’t even allowed to make the sandwiches. So her involvement in cooking only reached as far as watching her dad as a child, who used to “burn a lot of stuff”. Her mother also cooked but “neither of my parents were passionate about food”. But Adjonyoh certainly is passionate about it now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments