Olia Hercules: The chef who will make you want to visit Georgia

Olia Hercules’ first book offered the Ukraine on a plate. In ‘Kaukasis’, her second, it’s the Caucasus’s turn. She talks to Emma Henderson about her inspirations and places where flexitarianism and seasonality are not food trends but a way of life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After living in Ukraine, Cyprus, Italy and the UK, for Ukrainian-born Olia Hercules the recipes her mother and aunt made will always be comforting and homely for her, even though she’s now a Londoner. But for a chef who’s led a slightly nomadic life between countries that use food in such different ways, the most obvious thing to do is bring your old home to your new home in the form of food.

Following the troubles in Ukraine in 2014, Hercules worried her family recipes could be lost forever, so following a chat with her mum on Skype, she travelled back to her family in Ukraine to convert the recipes they held only in their heads onto paper. This became her first book Mamuska, which was published in 2015.

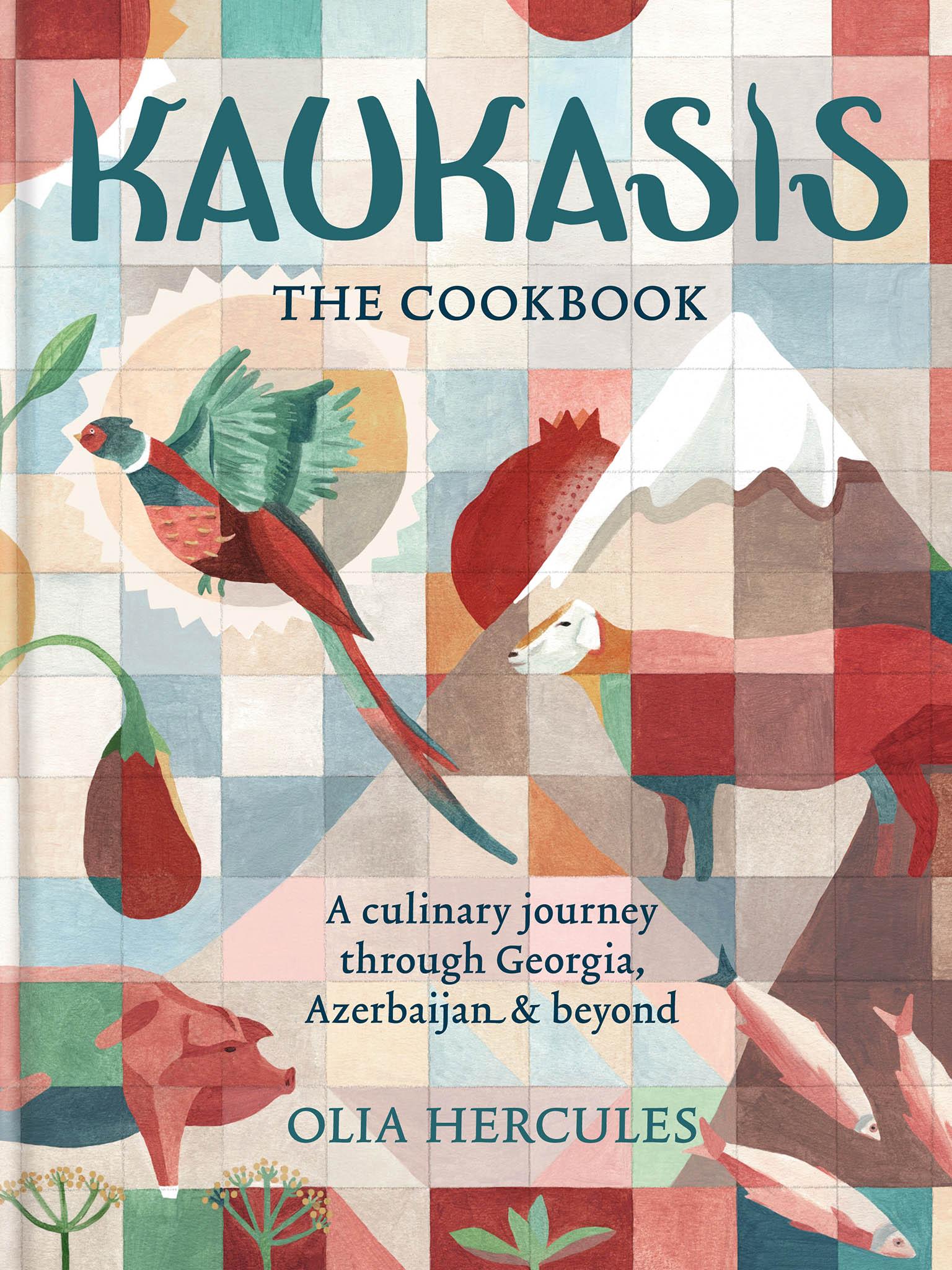

In her second book, Kaukasis – Greek for snowy-top mountain – she has spread her wings slightly further to include the Caucasus. It’s a cuisine rather untouched in the UK, often tarnished as being bland and grey, but Hercules transforms the “unknown” into an accessible, beautiful and in many instances a mouthwatering cuisine that’s become the book of the moment by taking us on – as the book’s title suggests – a culinary journey through Georgia, Azerbaijan and beyond.

Giving up her career as a journalist following the financial crash in 2008, Hercules turned her hobby into a career with an intense year of classical training at Leiths School of Food and Wine in west London, followed by working in restaurants – such as Ottolenghi – and making a living as a recipe writer and food stylist. But it was only in her early twenties that Hercules really started cooking. Moving to the UK to study at Warwick, she nurtured her cooking skills slowly, “and sometimes produced some really horrendous food” – as we all have done. And after a year spent in Italy, her love for food was cemented because of a Sicilian dish made from only three ingredients: spaghetti, sea urchin and olive oil.

The timing of her infatuation and severe change in careers was perfect – all things food from cookbooks to magazines and TV shows were taking off in the UK, and she had something to fill a very wide gap in the market, just by using the recipes of her family.

Hercules cleverly used what she has always known and grown up with to her advantage, which is evident in the first, and her favourite, chapter of Kaukasis, “Roots, shoots leaves all”. With recipes where the whole vegetables with roots and shoots still intact adorn pages, it appears as if the chapter was written especially for the trend of throwing as little food away as possible in the vein of wasteless guru Tom Hunt. But in reality, what Hercules has always known as seasonality is little more than the only way people can eat in many parts of the world.

“In the Soviet times, the food was quite bland and in the cities it was worse for them,” she says. For her, even as a child at the tail end of the USSR, it was a wealth of colour. “Ukraine is so regional, the north is earthier and the south is closer to the Mediterranean diet, growing aubergines and watermelon,” she adds. Her family lived in the south of Ukraine, in a port city called Kakhovka, where “from April to October it was super-hot, we grew our own vegetables and when you walk along the street apricots practically fall on your head.”

“I think seasonality is really important,” she says. “It was becoming super fashionable in the UK and if you have the best ingredients, it’s not hard to make something tasty.” Her favourite example of this is eating tomatoes in peak season and certainly not in winter when they have no flavour, and she sticks by her guns with her key advice – “just don’t cook dishes that are not in season”.

Hercules says she sometimes finds people complaining that good ingredients are expensive, but opposes such an idea because “you can make a shin of beef last a week and you can use more than leaves and stems of cauliflowers which taste just as good.”

For her it’s not about preaching about it, but she feels “people in the UK lost touch with that ethos” after the Second World War. And she’s right. A wave of convenience and disposable income meant we became lazy and wasteful. But we’re returning to a “use-all” ethos and eating less meat. “Now people call it flexitarianism, but it’s how we lived. My grandparents kept animals, but didn’t eat it every day. Meat was a treat.”

Hercules describes the book as being “Georgian with little injections of the surrounding countries” and that’s actually a rather accurate description of her family. Her grandmother was forced to escape the poverty of Siberia after the war and travelled to Uzbekistan: the only place where markets were still with food in the Soviet era. On the way she met her Ukrainian husband and the pair later moved to Ukraine. Her cooking naturally straddled Russian, Uzbekistani and Ukrainian dishes. While living in the south of the Ukraine meant Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan had natural influences in their regional cuisine.

Her second book was inspired by her aunt and a three-hour conversation which she recorded. They decided that “Georgia and Azerbaijan” were especially “rich in food and traditions” and she decided to do a research trip.

The trip was based on a spontaneous drive from Ukraine to Azerbaijan that her parents took the family on in 1986. Hercules was aged two and her brother 10. To put the journey in perspective, it’s nearly eight hours by plane – around 1,160 miles – and about 26 hours by car.

So in a pilgrimage as grown adults in 2015, the siblings followed the same route to the capital city of Baku, through Georgia. The trip began with a Facebook shout for friends of friends’ in Georgia to gain some local guidance. Contacts blossomed and their plans gave way to spontaneity – the people there were amazing, they found.

“Everything about Georgia charms the hell out of you, from the landscapes to the people and the food, and I could easily imagine being a chef there,” says Hercules. It made her want to move there but “the trance” was lifted after returning to her usual London life.

But it wasn’t just Georgia fever she came back with but 160 recipes which had to be cut down to 100. Her job was made easier with those requiring specialist items, like local cheese, for which there is no substitute in the UK.

And as well as the written recipes, she also returned laden with inspiration. When I asked who expecting a long list of chefs, she said it’s the people you meet along the way. And by this she specifically means the dedakatsi – a Georgian word which means “mother-man”. “They cook at home and they’re absolute masters at everything, with a natural instinct about how to do things,” says Hercules – women who do everything. “This is not feminism in the way that we all strive to achieve in the west, but altogether a different notion,” she writes in the book. “But it’s no less admirable.”

As with any cuisine that is new to the West, good restaurants are few and far between. But even in the 12 years Hercules has lived in the UK, she’s yet to come across a good Ukrainian or Georgian restaurant. Perhaps she’ll open her own and become her very own dedakatsi, but with having a five-year-old son too, it might be a little too early to do so. “Who knows, if the shop below becomes free, then we could do it from home,” she says, with a glimmer of hope.

Kaukasis is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments