Isn't it time the humble Cornish pasty had the coveted Unesco heritage status?

Neapolitan pizza has it, French baguettes are halfway there, so what about the humble Cornish pasty? Emma Henderson heats up the debate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Despite what some think, the Cornish pasty did not originate in Devon. Such blasphemy. But the veg-packed pastries have been gracing our tables, plates, hands – whatever you eat them from – since the 14th century.

And it’s fair to say the Cornish – and the rest of the country – have become quite attached to them. So much so, that tomorrow marks the first Cornish Pasty Week, celebrating just that.

But, a pasty can only be given the title of a “proper job” Cornish pasty if it was made in the county of Cornwall and in line with official guidelines. In fact, the real definition of the location is “west of the river Tamar”, which is practically the border between Cornwall and Devon.

So other pasties you see miles and miles away from the south-west county that don’t look like the classic D-shaped pasty with a traditional crimp to the side, please remember, that, yes, they are fakes.

And these traditional pasties have this protection thanks to the PGI status, which the real deal pasties have held since 1993. The PGI is a protected status from the European Union that defends produce from certain regions against imitation. Essentially, separating it from the diluted versions you see elsewhere.

To qualify as a traditional Cornish pasty – aside from where it’s made – the PGI standards state it must include having between 12.5 per cent and 25 per cent meat, along with potato, swede, onion and a little bit of seasoning.

Three places to get a real Cornish pasty

Chough Bakery: this family-run bakery mainly supplies north Cornwall from the seafood-famed Padstow to the tiny village of Port Isaac, but the award-winning pasties can also be found in Bristol and London – cornishpasty.com

The Cornish Bakery: using Cornish grown produce, with 13 flavours, from the BLC (bacon, leek and cheese) to the apple, rhubarb and custard, this artisan bakery began in Mevagissey and has spread country-wide to as far as Leeds and the Lake District – thecornishbakery.com

Warrens: as the oldest bakery to still be making pasties, the original being in St Just in Cornwall, it also has branches in Devon, Somerset, Manchester, Birmingham, Hampshire, Essex and London and offers 11 other varieties, including a vegan pasty – warrensbakery.co.uk

It must also be a D-shape with the curved edge crimped – now whether that’s crimped to the left or the right, that’s undecided and both are allowed.

Although what’s not allowed is the armadillo-style crimp, where a chunkier pasty has a centre crimp.

The ingredients all need to be uncooked when going into the pastry – which can be shortcrust, puff or rough – and shouldn’t break while it’s cooking either.

But these restrictive regulations were not always the way pasties were made. In fact, the meal was originally a vegetarian meal, free of the expense of meat. And that’s what cemented its association with working class families – a cheap and convenient way to feed people.

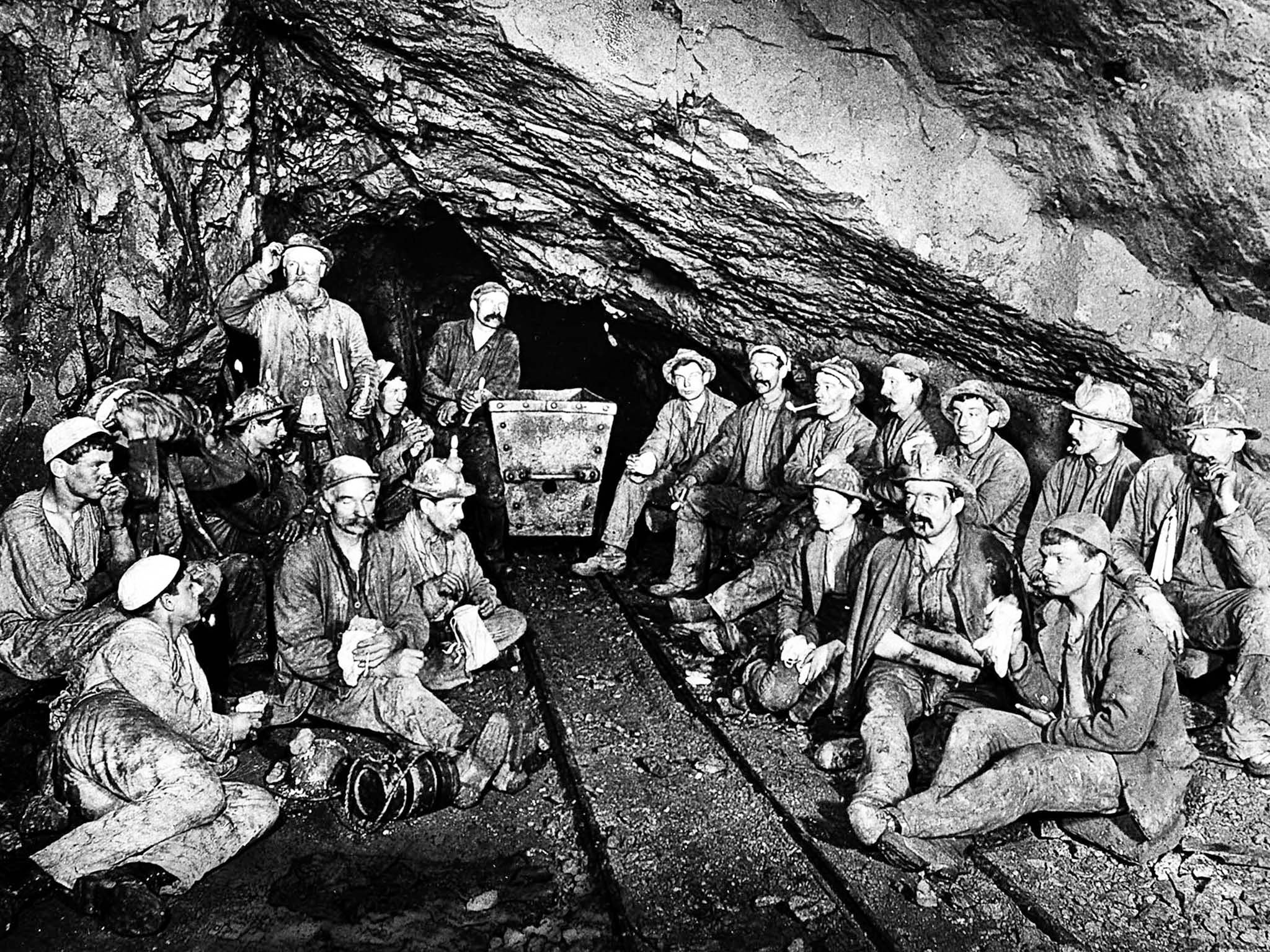

It is, though, one the original takeaway meals, which were used across the county during the 19th century; a full meal to eat out of the house for miners working in deep mines where they spend an entire day. The ingredients are cheap, and the luxury of meat was not added again until much later.

And what’s also changed is the crust. Today, it’s a much loved part of the meal, but at the time the miners were eating them, it was actually used as a handle to carry the meal and would be pulled off and discarded because of the miner’s dirty hands. But this point is disputed, as some say the pasties were wrapped in something, but we prefer the former idea.

Even though tin mining has long since lost its momentum, and the last Cornish tin mine, South Crofty, only closed 20 years ago, the food of the mines has outlived the job it was created for.

It’s not only survived, but it’s flourished. The Cornish pasty is part of the cultural heritage of Cornwall. The industry accounts for around £300m of trade per annum and employs 2,000 people (most are full-time and year-round), according to the Cornish Pasty Association.

But why has the Cornish pasty not been awarded a Unesco world heritage status, much like the pizza of Naples recently was in December 2017, as part of the regime to raise awareness of traditions around the world. And the same could be said for the French baguette as well.

Jason Jobling, master baker of Cornwall’s longest running bakery, Warrens, says the pasty has managed to stand the test of time because it’s a “good, filling and honest meal classic to Cornwall and the British cuisine, containing fresh vegetables and meat. Away from the traditional Cornish Pasty flavour, the pasty has become a great carrier of many interesting and well-received flavour combinations. Easy to eat, it is the ultimate grab-and-go food.”

So have a little thought the next time you see an oddly square-shaped “pasty” at a fast food counter in Paddington train station that’s never seen the light of day in Cornwall, or one with the crust along the centre and not the side. Maybe save your money for the next time you come across the real thing.

I’m sure it will taste a whole lot better.

A genuine Cornish pasty recipe from the Cornish Pasty Association

For the shortcrust pastry (rough puff can also be used)

500g strong bread flour (it is important to use a stronger flour than normal as you need the extra strength in the gluten to produce strong pliable pastry)

120g lard or white shortening

125g Cornish butter

1 tsp salt

175 ml cold water

For the filling

450g good quality beef skirt, cut into cubes

450g potato, diced

250g swede, diced

200g onion, sliced

Salt and pepper to taste (2:1 ratio)

Beaten egg or milk to glaze

Rub the two types of fat lightly into flour until it resembles breadcrumbs. Add water, bring the mixture together and knead until the pastry becomes elastic. This will take longer than normal pastry but it gives the pastry the strength that is needed to hold the filling and retain a good shape. This can also be done in a food mixer.

Cover with cling film and leave to rest for 3 hours in the fridge. This is a very important stage as it is almost impossible to roll and shape the pastry when fresh. Roll out the pastry and cut into circles approximately 20cm in diameter. A side plate is an ideal size to use as a guide.

Layer the vegetables and meat on top of the pastry, adding plenty of seasoning. Bring the pastry around and crimp the edges together (see our *guide to crimping). Glaze with beaten egg or an egg and milk mixture. Bake at 165C (fan oven) for about 50-55 minutes until golden.

Top tips: beef skirt is the cut traditionally used for Cornish pasties. This is the underside of the belly of the animal. It has no gristle and little fat, cooks in the same amount of time as the raw vegetables and its juice produces wonderful gravy. Use a firm waxy potato such as Maris Peer or Wilja. A floury potato will disintegrate on cooking.

*Guide to crimping

Lightly brush the edge of the pastry with water. Fold the other half of pastry over the filling and squeeze the half-circle edges firmly together. Push down on the edge of the pastry and using your index finger and thumb twist the edge of the pastry over to form a crimp. Repeat this process along the edge of the pastry.

When you’ve crimped along the edge, tuck the end corners underneath. The finished pasty, ready to bake.

The first Cornish Pasty Week begins 25 February and culminates with the Cornish Pasty World Championships on 3 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments