‘My dad had early stage cancer but he died of Covid-19 following a hospital appointment’

On 18 March Stuart Goodman was invited to sit in a busy hospital waiting room to hear his cancer diagnosis; 15 days later he died from Covid-19. Now daughter Jo tells Sophie Gallagher why the family feel let down by the government

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

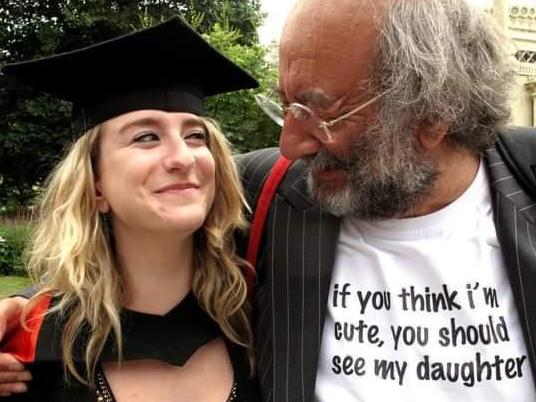

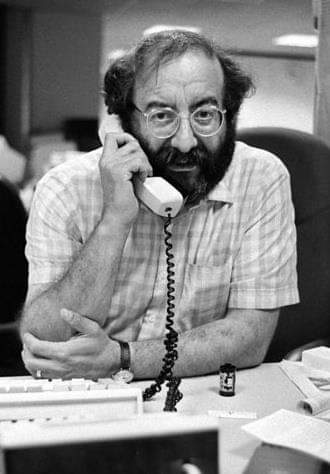

Your support makes all the difference.“I 100 per cent hold the government responsible for my dad’s death,” Jo Goodman, 31, tells TThe Independent the day after the funeral of her dad Stuart Goodman, a former Evening Standard picture editor and photographer, who died from coronavirus aged 72. “They [the government] treated people like my dad as expendable and it was totally avoidable if they’d acted sooner."

In November 2019, Stuart attended a routine scan at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NNUH) following heart bypass surgery seven months earlier. During the scan doctors discovered a tumour on his spleen but believed it was a slow-moving and non-aggressive cancer so an exploratory biopsy was pencilled in the diary for after Christmas.

On New Years’ Eve the World Health Organisation (WHO) received the first reports of a previously-unknown virus in Wuhan, China, causing severe cases of pneumonia. The coronavirus, as it was later identified, gathered pace throughout January and soon the city of 11 million people was placed in lockdown to contain the spread. Over 5,400 miles away the Goodman family were awaiting the results of Stuart’s biopsy.

On 18 March, Stuart and his wife Annie, 68, were invited to attend the diagnosis at NNUH. Jo and her 30-year-old brother Adam were anxious about their vulnerable father - who was over 70, mildly asthmatic, had undergone heart bypass surgery, and now likely in the early stages of cancer - sitting in a crowded waiting room with other vulnerable patients.

By 18 March there had been 201 Covid-19 deaths in England and there would be a further 103 on that day alone. Although the government had released risk factors – age and underlying health conditions – it had not explicitly told vulnerable people to start shielding (that wouldn’t happen until 21 March when letters were sent to 1.5 million British homes).

Nevertheless Stuart and Annie had begun self-isolating at home on the insistence of their children and wouldn't have been going out if it weren't for the appointment. “We didn’t understand why, at that stage, the diagnosis couldn’t be done over the phone. My parents said they ‘wished they didn’t have to go’,” explains Jo.

Spokespersons for both the NNUH and NHS England told The Independent all decisions to invite patients in to the hospital in mid-March were based on government guidance.

“We have carefully followed the national Public Health England advice during the Covid-19 pandemic in what has been a fast moving and unprecedented situation,” they said. “This was government guidance and we changed policies on the back of that.”

A spokesperson for the department of health and social care told The Independent: “We published guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK on 16 March, which also included advice for people with cancer undergoing active chemotherapy or radiotherapy.” (Stuart was not yet undergoing any treatment).

In Boris Johnson’s speech on 16 March he did advise vulnerable people but what he told them was that they did not need to begin shielding until the weekend, saying: “In a few days’ time – by this coming weekend [21-22 March] – it will be necessary to go further and to ensure that those with the most serious health conditions are largely shielded from social contact for around 12 weeks."

He even explained why people did not need to begin immediately: “The reason for doing this in the next few days, rather than earlier or later, is that this is going to be very disruptive for people who have such conditions, and difficult for them.”

This message that shielding could wait until the weekend – coming just days after 250,000 people gathered at Cheltenham Festival on 10-13 March – meant that if you didn’t read between the lines, the message was that you were fine to continue as normal: “The government didn’t give the right cues so people weren’t as concerned as they should have been at that point,” says Jo.

Not to mention Stuart was being invited by the hospital – not choosing to go out himself: “My dad was so respectful of the NHS and doctors he trusted it was the right thing to do.”

On that day Stuart was told he had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – a cancer of the lymphatic system. But with chemotherapy his prognosis was good, doctors predicted a 70 per cent chance of survival. The family returned home, forgetting their fears about the coronavirus instead bracing themselves for the months of cancer treatment ahead.

They said even if somehow he did pull through the likelihood of him coming off the ventilator would be slim to none so his quality of life would have been non-existent..."

But their concern had not been misplaced. Ten days after visiting the hospital Stuart started to exhibit signs of coronavirus: he had a cough and became so feverish he didn’t recognise his wife. On Sunday morning Annie decided to call an ambulance to take him to hospital. The paramedics arrived and took him back to NNUH where he tested positive for Covid-19.

“As soon as he was diagnosed we knew he wouldn’t make it short of a miracle because by this point his immune system was so compromised,” explains Jo. “Before, when they released the risk factors, we had looked at them and thought ‘he’s got a target on his head if he gets it’”.

Stuart wasn’t put on an intensive care ward, even though his prognosis was poor. Doctors had decided not to put him on a ventilator, a decision made, Jo says, due to the “perfect storm” of health problems her father was dealing with. Although she agreed with the doctors she found it hard. “The doctors explained to me that it wouldn't work for someone so 'frail'. That was hard to take as despite his health conditions I'd never really thought of him like that.

“They said they didn’t want his last conscious experience to be a traumatic one. They said even if somehow he did pull through the likelihood of him coming off the ventilator would be slim to none so his quality of life would have been non-existent.”

The family trusted the judgement of the doctors and accepted their decision. But Stuart deteriorated quickly.

“It was such a horrible illness, even if I saw him a few hours apart you could see it was eating him up – it was like watching something take over your dad’s body and it’s such a weird thing watching your dad go through something you see in the news,” says Jo. Unlike other families, the family were permitted to visit and did not have to wear full PPE (personal protective equipment) on the ward, just aprons, gloves and non-surgical masks - as the staff were wearing.

On Thursday 2 April, 15 days after attending an appointment in the same hospital, Stuart died from Covid-19. His social-shielding letter, telling him to stay at home, arrived in the post nine days after his death.

“This wasn’t the way or the time at which he should have gone. He had a good chance of surviving the cancer. I should have had my dad for many more years, he should have met his future grandchildren,” says Jo. “The world is a different place without him.”

The family places the blame for his death squarely on the government for not implementing a lockdown earlier. This would have meant that her father didn’t need to go to the hospital for his diagnosis, instead having a phone consultation, or at the very least that the hospital was required to implement social distancing measures in waiting rooms.

“The UK had the benefit of a headstart – watching other countries deal with it - we should have had that lockdown earlier,” says Jo.

The family maintain that watching Stuart die from cancer wouldn’t have felt quite as unjust as it did watching him suffer with Covid-19. “The cancer would have been horrendous but it was life’s plan. Instead something swooped in from the outside, that could have been prevented, and took him away from us so quickly.

"Thankfully the doctors and nurses gave dad the best treatment in the most challenging of circumstances and we are so grateful."

A DHSC spokesperson added: “Every death from this disease is a tragedy and we are working round the clock to keep the nation safe. This virus can sadly have a devastating effect on some of our most vulnerable people."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments