I thought I just needed new glasses – then doctors told me I was going completely blind

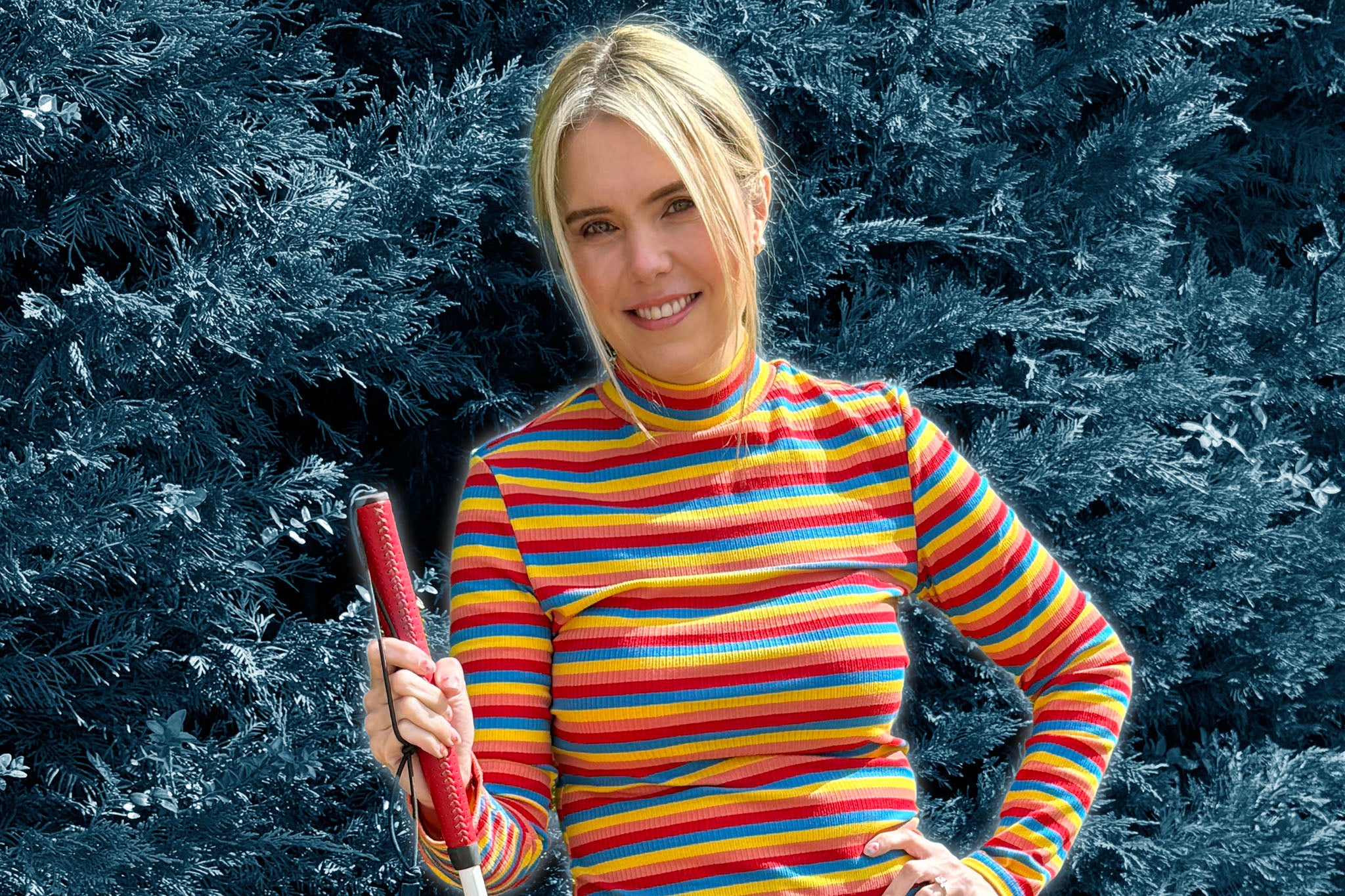

Following a stroke, presenter and disability advocate Claire Sisk, now 44, gradually lost her sight over the course of eight years, finally becoming registered blind in 2017. She tells Helen Coffey how she managed life with a young daughter and the misconceptions that surround her condition

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was in April 2009, at the age of just 29, that I had my first stroke. Six months later, in September, I had another one. That November, once I was back at work, I was driving home one day and realised I couldn’t quite see the road signs. I wore glasses then, so I just assumed my prescription had changed. I booked an appointment with the optician.

They could see something in my eye and sent me to A&E. When they looked at my eyes, they saw that my rods and cones – the eye’s light receptors – had been affected by my stroke. When they did more tests, they saw there were lots of different diseases attacking my eyes. The core cells were gradually dying. Doctors predicted that, by the age of 40, I would potentially be completely blind.

Even with all the different diagnoses, I was told that, while my core vision would continue deteriorating, my peripheral vision should stay intact. But in 2013 I started noticing patches of this were going as well. That’s when they took my driving licence off me. For the next four years, it was a progressive deterioration; all my core cells were dying. On the first day of November 2017, I woke up with very, very little vision: no core vision whatsoever, and the tiniest amount in the top left hand corner of my peripheral field. I saw my ophthalmologist the same day and she confirmed that all the cells had died. That was it. This was now my vision. That’s when I was registered blind.

I was a single mum with a nine-year-old daughter when it all started happening. That was the scariest part – I was quite naïve and thought that they might take my daughter away from me. I was also scared that I would lose my job. Because of that, I hid what was going on from my employer for four years – I only told them when I was registered as visually impaired in 2013. I really thought that they would sack me.

When I finally opened up, they were incredible. Initially, though, all I could think was that I was a single mum with a mortgage. If I lose my job and I can’t look after my daughter, I thought, what’s going to happen? It’s a really scary position to be in.

Because my sight loss was gradual, and they’d told me the chances were I’d be blind by 40, I had this mentality that I would be the best bloody blind mum ever. I practised doing everything at home with a blindfold on or with my eyes closed: I learned to cook, chop, prepare food, clean, do my makeup. I was prepared. But the reality of actually waking up without your sight is very, very different. You’re expecting it, but you’re not. Every day I kept thinking, “Oh, I’ll wake up and it’ll be back tomorrow”. But every day that it went on and my vision didn’t come back, it was like, OK, you’ve got to get to a stage where you now accept that this is your life. That is a really hard thing to do.

It’s not OK is to judge and assume. I once got accused of pretending to be blind because I was using a mobile phone. That sort of accusation blows my mind

Going blind as a single mother was a challenge, but we’ve never let it stop us doing the things we want to do. We adapted. My daughter is an incredible person, my absolute rock, and we’ve got this incredible bond. When she went off to university, the hardest thing was her not being here, not me being blind. I feel like, actually, out of anything in my life, that was the most difficult to process and accept – not going blind, but my daughter going away and having an empty nest. These days, I live with my partner, and my daughter has moved back in with us, and my partner has two children who come and go as they please. We’ve got a really chilled, relaxed, fun, happy family. No two days look the same.

One of the hardest things to adapt to was walking everywhere instead of driving. I drove from the age of 18, and to have your licence taken away… you feel you’ve lost all your independence. You’re suddenly relying on public transport and lifts; trying to get my daughter to school and myself to work on time was a struggle. As was going food shopping and having to carry all those heavy bags on the bus… When you’re registered as sight-impaired, you’re not entitled to any form of benefits. So even though you’re not allowed to drive, you have to be registered as “severely sight-impaired” to even get a free bus pass. It’s a huge expense as a person with a disability, which people often forget – you know, taxis every week to get your food shopping or to go to parents’ evening.

It is really hard sometimes. Even now, I still find things that I’m like, “Oh, I have to change the way I do that because I can’t see.” But it forces you to think outside the box, which can actually be a good thing – because not many of us do that unless we’re forced to. Every day, I’m forced to think differently and adapt to a new way of doing things.

Having said that, it’s the last thing you want to be thinking about when you’re going through it – like, trying to problem-solve how to get a spider out of the bath when I can’t see, because my daughter is scared of spiders and won’t go in there! It’s difficult, but you figure it out. You get on with it because you have no other choice.

It took me years to accept I was going blind. As it got worse, I didn’t go out a lot because I felt like a bit of a burden on everyone. Not that anyone ever said that to me – and, looking back, I kind of regret this huge chunk of my life when I didn’t do anything. But then, between 2017 and 2019, I really worked on accepting what had happened to me and started using my cane more. There was a week when I stood on someone’s dog, fell out of a bus, and almost got hit by a car. That’s when the reality hit me that I needed to start using my cane. And the day I started using Rick the Stick – yes, I’ve named him! – it’s like my life changed. My biggest regret is not doing it sooner, because I felt like I got my independence back. I felt like I could start being me again.

Some people are very ignorant about blindness. The minute you say you’re blind, they automatically think you can’t see anything at all. A lot of people don’t realise that less than 10 per cent of those who are registered blind literally see nothing. The rest of us have got some colour perception or light perception; we might see shapes and shadows. It’s a spectrum – not every blind person is going to be the same. It’s OK to ask questions about it, but what’s not OK is to judge and assume. I once got accused of pretending to be blind because I was using a mobile phone. That sort of accusation blows my mind.

Another no-no: please don’t grab me when I’m getting off the Tube! People tend to grab you and drag you, and it’s quite startling. I think I’m being mugged or something. It’s fine to offer help, but do it in the correct way. I always say to people, if you’re wanting to help someone, announce yourself. If I need help, I’ll happily take it. If I don’t, I’ll just say, “No, thank you, I got this.”

I do think going through something so life-changing has made me a better person. I appreciate life so much more than I ever did before. I’ve always been quite an empathetic and caring person, but I think even more so now. I’m incredibly grateful for all the opportunities I’m getting at the moment; that I’m able to use my social media to help people who are also going through sight loss and show the world that having a disability doesn’t stop you from doing things.

I get so many DMs on Instagram, and it’s such a beautiful community to be in. Together, we all support each other and share our tips and tricks. To be able to have a positive impact on one person – that’s all I ask for in life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments