Sight loss could be treated by antibiotics after being linked to gut bacteria

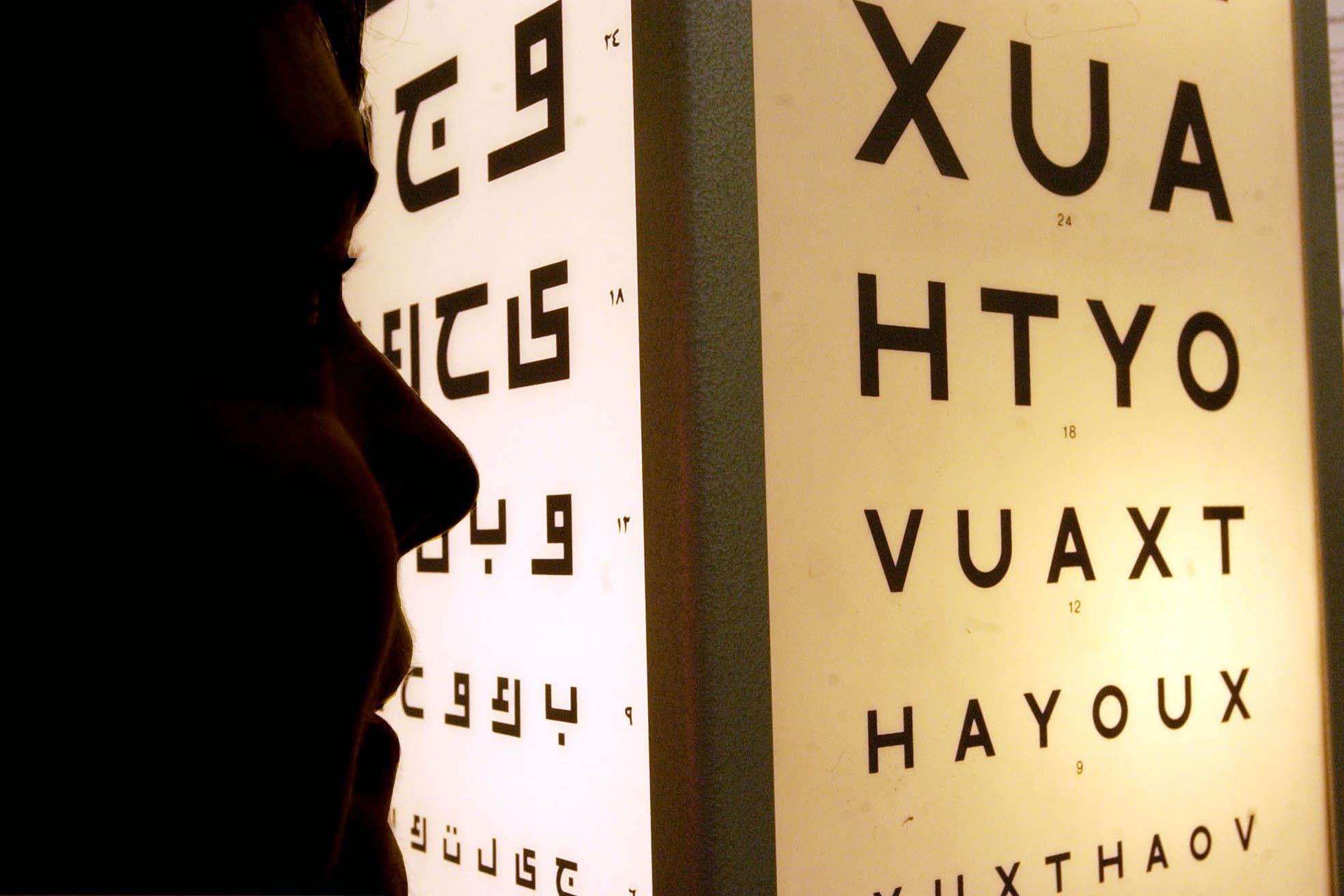

Inherited eye diseases are the UK’s leading cause of blindness in working-age people

Sight loss in some inherited eye diseases may be caused by gut bacteria, and could potentially be treated with antibiotics, new research suggests.

The study in mice found gut bacteria within damaged areas of eyes where sight loss was caused by a particular genetic mutation.

According to the researchers, their findings suggest the genetic mutation may relax the body’s defences and allow harmful bacteria to reach the eye and cause blindness.

The gut contains trillions of bacteria, many of which are key to healthy digestion.

However, they can also be potentially harmful.

Co-lead author Professor Richard Lee, of the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, said: “We found an unexpected link between the gut and the eye, which might be the cause of blindness in some patients.

“Our findings could have huge implications for transforming treatment for CRB1-associated eye diseases.

“We hope to continue this research in clinical studies to confirm if this mechanism is indeed the cause of blindness in people, and whether treatments targeting bacteria could prevent blindness.

“Additionally, as we have revealed an entirely novel mechanism linking retinal degeneration to the gut, our findings may have implications for a broader spectrum of eye conditions, which we hope to continue to explore with further studies.”

In the study the researchers were investigating the impact of the Crumbs homolog 1 (CBR1) gene, which is crucial to regulating what flows in and out of the eye.

The gene is associated with inherited eye disease, most commonly forms of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) and retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and is the cause of 10% of LCA cases and 7% of RP cases worldwide.

The scientists discovered that in the lower gut the gene combats disease and harmful bacteria by regulating what passes between the contents of the gut and the rest of the body.

The team found that these barriers in both the retina and the gut can be breached when the gene has a particular mutation which reduces its effect.

This allows bacteria in the gut to move through the body and into the eye, leading to lesions in the retina that cause sight loss.

According to the study, treating these bacteria with antimicrobials, such as antibiotics, was able to prevent sight loss in the mice even though it did not rebuild the affected cell barriers in the eye.

Further research will need to look at whether this applies in humans.

Inherited eye diseases are the UK’s leading cause of blindness in working-age people.

Deterioration of sight loss is irreversible and has lifelong implications.

To date, the development of treatments has largely focused on gene therapies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks