Solving labour shortages won’t be easy – but we can start by making jobs more attractive in a post-Covid world

The pandemic has created more demand for some jobs but cut demand for others, says Hamish McRae. But it’s the changed relationship between workers and employers which will have the greatest impact

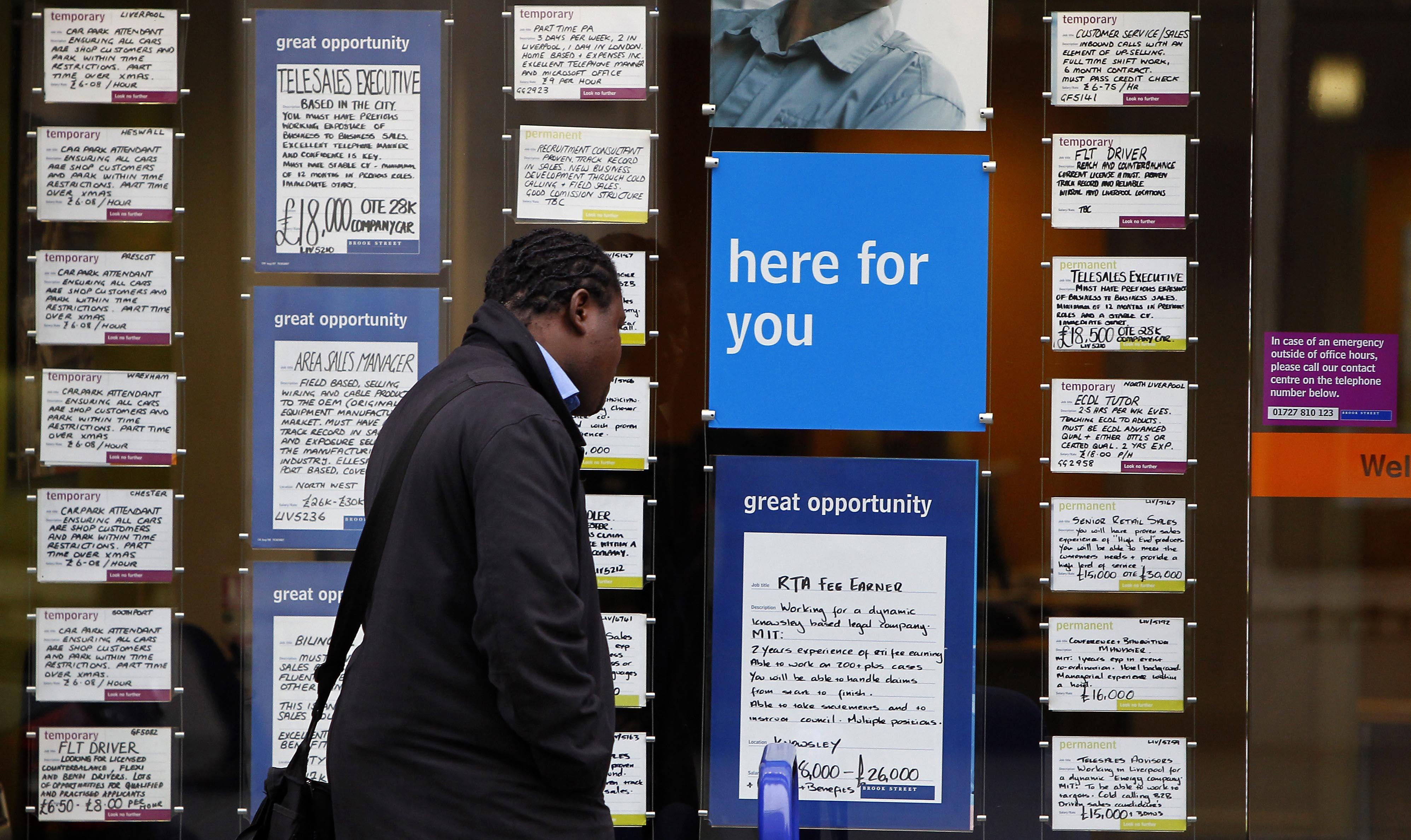

Labour shortages are everywhere across the developed world. They are very evident in the UK, with many fuel stations still closed, dishes taken off restaurant menus, and gaps on supermarket shelves.

But the same thing is happening in the US. The New York Times ran a column last month entitled “Good News. There’s a Labor Shortage”.

Germany needs another 400,000 skilled workers every year, according to the head of the Federal Employment Agency, Detlef Scheele. France is short of 40,000-50,000 lorry drivers, according to the prime minister, Jean Castex. Italy struggled to harvest its fruit crops this summer, while the other G7 nations, Japan and Canada are hit by a lack of workers too.

The flip side of labour shortages is unemployment. As far as the UK is concerned, you would have expected that with the furlough scheme ending, unemployment would shoot up. But that does not seem to be happening. We get new figures on Tuesday, but the previous data showed it at 4.6 per cent. That compares with 4 per cent before the pandemic struck, but is 0.3 down on the previous quarter. Again, much the same pattern seems to have emerged in other countries. Thus the latest US unemployment rate is 4.8 per cent, pretty much the same as the UK.

So what’s up? The disruption from the pandemic has created more demand for some sorts of jobs but cut demand for others. So there is a mismatch. But what seems to be happening is something more lasting, a transformation of the relationship between workers and employers. Power has shifted in a radical and lasting way. Labour markets will be tight for years to come, with unemployment down to levels that have not been seen for half a century and more.

In the final three months of 2019, UK unemployment was 3.8 per cent. That was the lowest since the end of 1974, lower than at any stage during most people’s working lives. But go back a bit further, to the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and you find that unemployment was in the 2-3 per cent range.

Given the combination of ageing societies not only across the developed world, but also in China, that may become the new normal again.

If this is right, and I think it is, this radical shift of power will change everything. It will bid up wages and we are already seeing that. There is certainly a danger that the world will get back into the wage/cost spiral that took off in the 1970s, leading to double-digit inflation that eventually was crushed by very high interest rates. Let’s hope that does not happen. But in any case several other changes will take place.

For a start, employers will have to find ways of making jobs more attractive, and not just by paying people more money. An obvious example is more flexible working conditions. Another is true career development, not simply essential training to do the current task. Fringe benefits, such as help with accommodation, will surge. In short, employers will seek all sorts of non-financial ways of attracting and retaining workers, while trying to hold their costs down.

They will also try to build loyalty. Employment will become transactional, or at least explicitly so. There will be less of a hire-and-fire culture, simply because if you fire someone you may struggle to hire someone else to do the job. There may well be less outsourcing, though that is not clear. Much will depend on comparative costs. But I suspect that the cost advantages of outsourcing will tend to narrow.

It is not clear, either, whether the shift to the gig economy will grow or shrink. It may suit companies to regularise the conditions of their part-time, self-employed workers, not so much because regulations will be tightened – which is happening across Europe – but because their businesses work better with a more stable workforce. At least it is plausible that the gig economy has peaked.

The most important change, however, will be one of atmosphere. Put bluntly, if jobs are scarce, employers all too often exploit that and treat people badly. If it is hard to attract people, they have to behave better. Of course, workers can behave badly too, but maybe – here’s a hope – as everyone becomes accustomed to the new relationship, we will move to a more courteous relationship in the workplace.

None of this will happen suddenly. There is likely to be a couple of years of economic disruption ahead, and then a decade or more as new work practices settle down. Then some other shock will come along and change everything again. But the big point here is that the post-Covid working world will be quite different to the pre-Covid one. They were changing already. Now we have all been catapulted into new and different times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments