Biden is looking more presidential – but if he wins, he may not be as friendly to the UK as we assume

Europe and Brexit Britain cannot afford to be seduced by a return to the past that is not going to take place, writes Mary Dejevsky

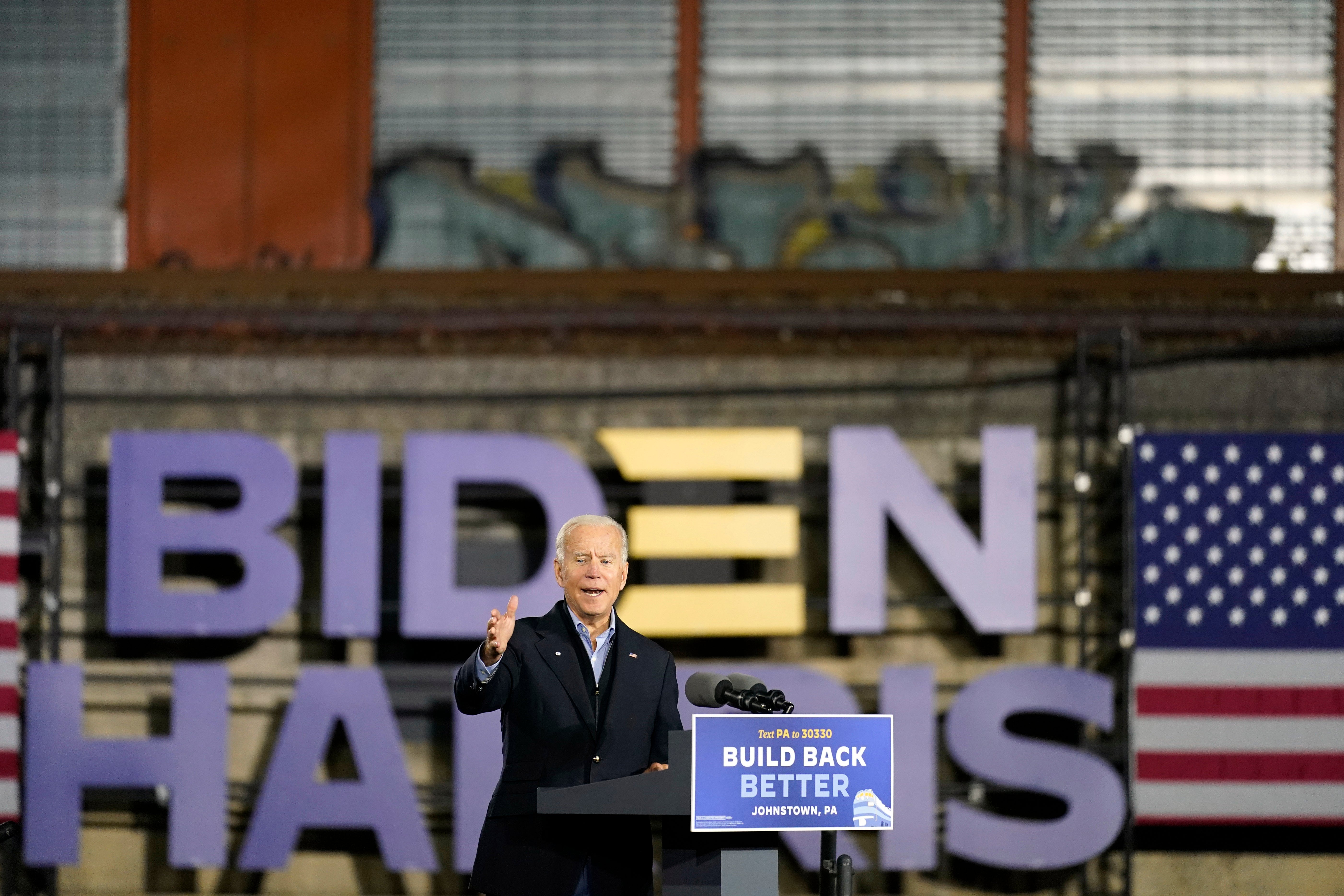

Maybe it is just my imagination. But it seems to me that the first week of October has marked a sharp change, a transformation even, in the presidential campaign of Joe Biden. Suddenly, he is behaving like a man who has stopped hoping and started believing that he can win.

The change is not about the polls, although these show that the Democrat’s lead over president Donald Trump increased after the first televised debate on 29 September, and again after Trump’s brief stay in hospital with coronavirus. The current aggregate of US polls has Biden nine points clear, though many show the gap much wider.

Nor is it about the content of his speeches. If you read the transcripts of his latest addresses, at rallies in the swing states of Michigan and Florida, you will find them similar to his speeches before then: a tad too long, and with the same awkward combination of folksy and wonkish as before.

But watch how he delivers them. This is no longer the candidate who was supposedly crouching in his Delaware basement, reluctant to emerge into a world of pandemic and engage directly with his bombastic foe. His body language and tone have changed. They are suddenly those of a president. It is almost as though the evidence of Trump’s physical vulnerability gave him permission to take on the mantle.

He is no longer the eternal vice-president. Indeed, he has his own vice president-in-waiting, who acquitted herself competently in her own debate with Trump’s vice president, Mike Pence. If the first law of a vice presidential debate might be to do no harm – either to your own political reputation or, more important, to that of the presidential candidate – she succeeded. So far, in a contest where the age of both candidates casts the spotlight on the running mates more than usual, Kamala Harris has demonstrated that she is no liability.

Now, a lot can still go wrong for Joe Biden before 3 November. Illness, it has been starkly illustrated, stalks the land. Donald Trump has a fiercely loyal base that may turn out to be larger than advance polling suggests. Either Biden or Harris could still make costly mis-steps on the way. Plus Trump is a formidable campaigner, who relishes the fight in a way that, in the past at least, Joe Biden has seemed not to do.

But the start to October has allowed Democrats to hope, perhaps for the first time during this campaign. And not just US Democrats, but all those around the world, especially in Europe, where a Biden presidency is widely seen as presaging the return to a blissful normal, after an aberrant four years. How far such hopes are justified, however, is another matter. I fear they reflect dangerous wishful thinking, based on distaste for Donald Trump and Trumpism and a misguided nostalgia for the Obama years.

I would single out two likely misconceptions about Biden foreign policy.

The first is that a Biden administration would be more orientated towards and supportive of Europe than Trump has been, or would be were he to win a second term.

Certainly, as an old-style east coaster, Biden would be superficially more amenable to Europeans, including Britons. His chosen officials and top diplomats would be more likely to find a common language with London, Paris and Berlin. How far this change would extend beyond manners and predictability into substance, however, is another matter. One of the most coruscating critiques of Europe, for not contributing enough to the Nato alliance, for instance, came not from Trump, but from Obama’s then outgoing defence secretary, Robert Gates, in 2011, when he warned that Nato risked “collective military irrelevance” unless Europeans contributed more.

Obama – born and educated in Hawaii, with a not altogether flattering view of the UK – was seen in some quarters as the first “Pacific president”, although Bill Clinton had already foreshadowed a 21st century need to “pivot” towards Asia. Europe’s elite loved the idea of Obama: as the first black US president, as a Democrat, a social liberal, and someone of an intellectual bent. But it is probably fair to say that Europe was not a foreign policy priority in the way it had been for presidents who remembered the Cold War and who might themselves, or had relatives, who had served in the US military in Europe. Biden may, in theory, belong to that generation, but – so does Trump – and what his election showed was that the United States had moved on.

Which leads to the second misconception. Trump is little different from Obama in his isolationism; he is just brasher and more boastful about it than his predecessor. He has also been more successful in defying his top brass to insist on US military withdrawals, whether from Iraq or Afghanistan – or Germany. US involvement in Syria remains largely under wraps.

The US has eschewed most foreign intervention now for 12 years. Obama was elected in part because of his opposition to the Iraq war, which has left its mark on US voters as it has on their contemporaries in the UK. He declined to embroil the United States in Ukraine after 2014, in Libya (except to rescue the UK and France in extremis), or – overtly – in Syria, where he attracted some domestic opprobrium for not honouring his self-imposed “red line” after the Syrian military’s alleged use of a chemical weapon.

Obama would never have proclaimed anything so vulgar as “America First”, and Trump went out of his way to present himself as the “non-Obama” in every way. But the two have far more in common in their non-interventionism, and the rejection of global leadership that implies, than either would admit. Biden has given no indication that he would reverse this.

So, while it is surely premature to treat the US as a declining power in terms of military might and wealth, it is hard to see the next president, whoever it is, seeking or obtaining a mandate to enforce a new Pax Americana. Europeans who are counting on American protection in perpetuity will have to get used to that. Whether it is expressed in terms of trying to forge new alliances in the Pacific or challenging China on trade (as Trump has done), the US “pivot to Asia” is well underway.

More predictability and civility in foreign relations, and a greater cultural sensitivity towards Europe, of course, are not nothing, and to this extent, a Biden presidency could improve the transatlantic atmosphere. But Europe and Brexit Britain cannot afford to be seduced by a return to the past that is not going to take place. US foreign policy priorities are not the same as they were 20 years ago and Joe Biden’s superficial European-ness is not going to change that. At most, they – we – will have a four-year breather to adapt to the self-reliance that will have to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks