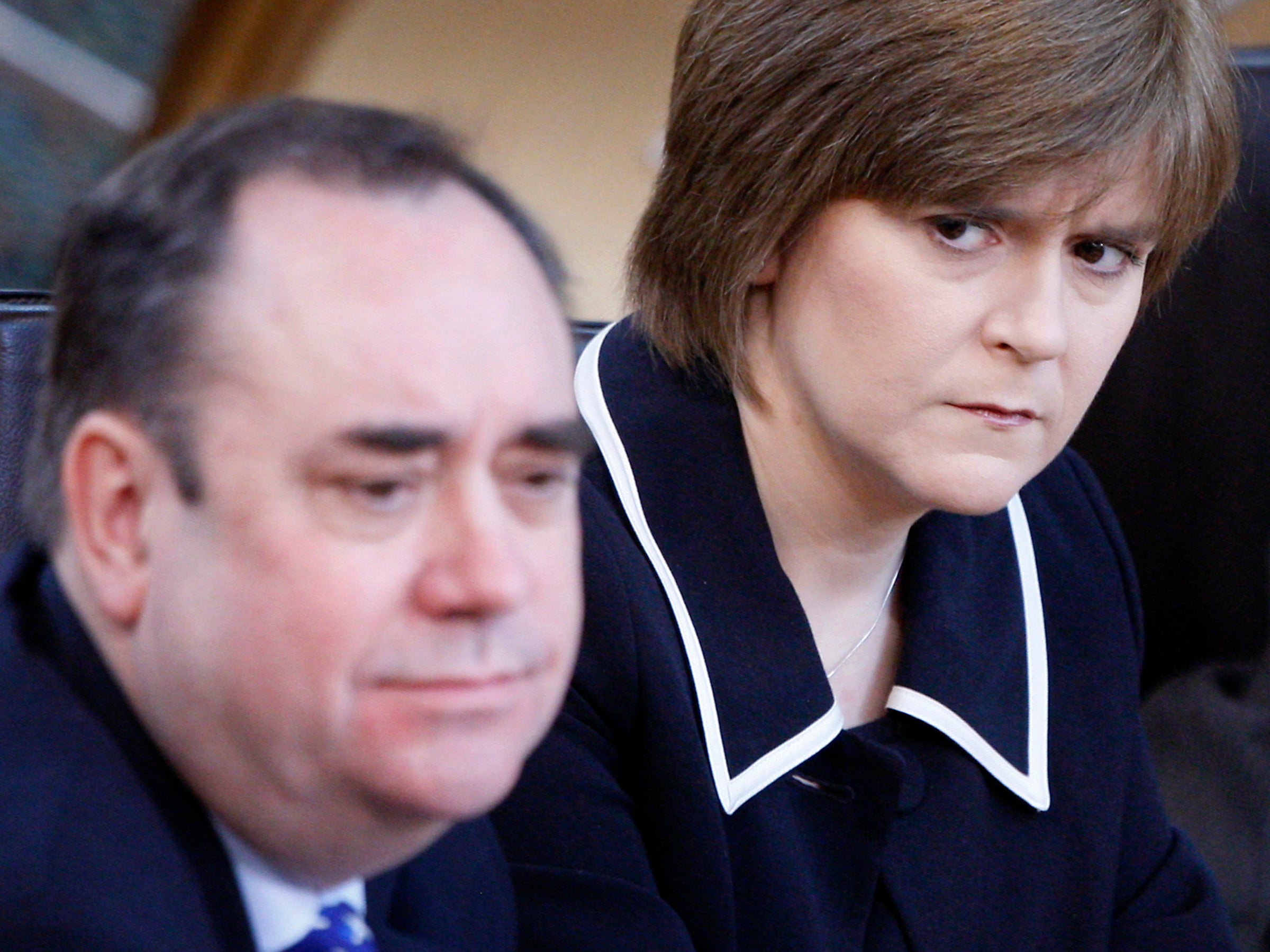

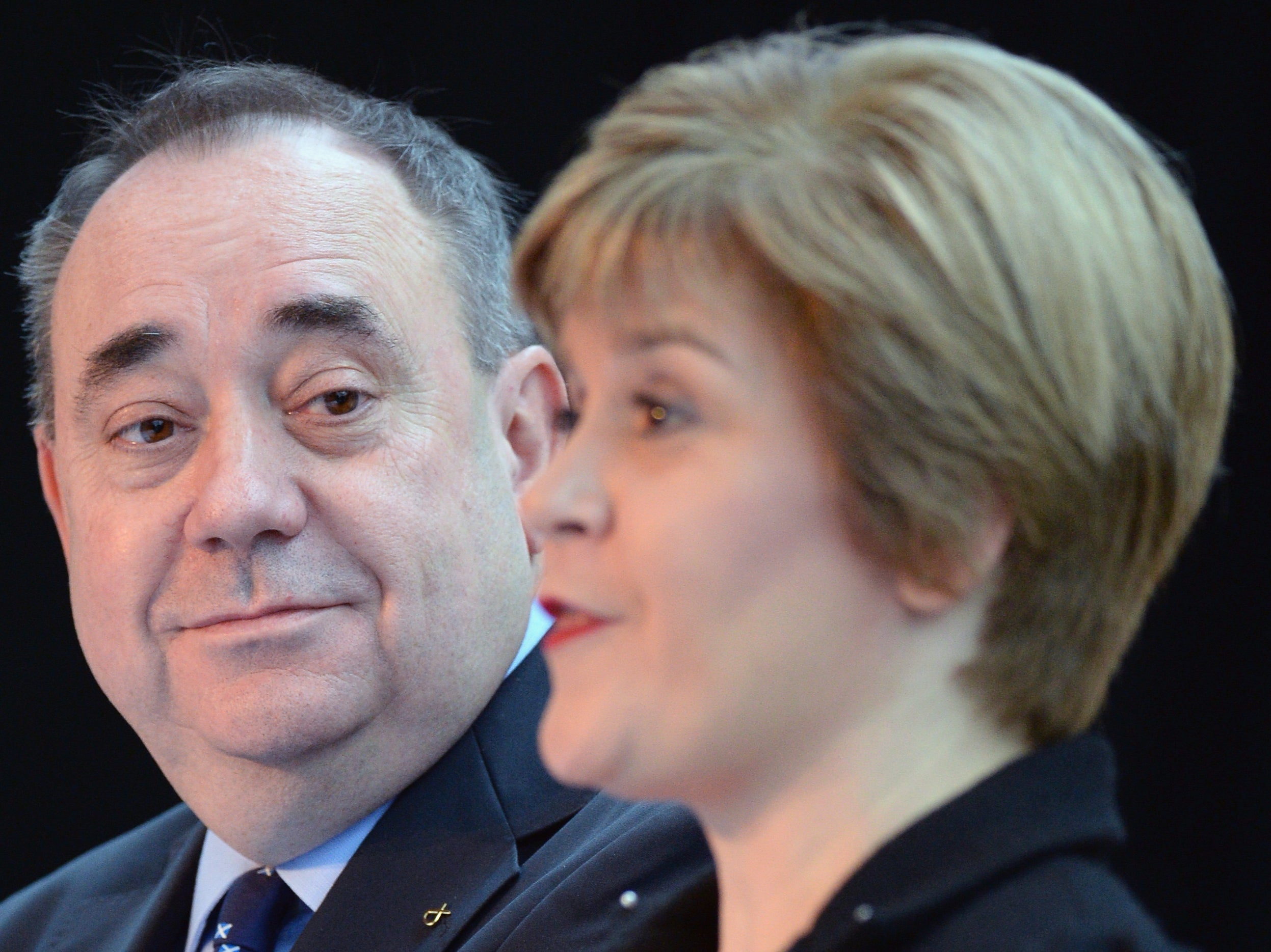

Nicola Sturgeon: The champion of Scottish independence fighting for her political future

With an independent Scotland now a distinct possibility, a feud with her predecessor means the woman at the heart of the campaign may not be in power much longer. Sean O’Grady explores Nicola Sturgeon’s extraordinary rise... and considers the implications of her potential fall

The biggest barrier to understanding the Salmond-Sturgeon row is to try and understand it. It is impossible to do so in all its glorious technicolour tartan majesty. Like the most breathtaking of Highlands scenery, there’s just too much to take in. Contemplating it is a bit like the old joke about the Schleswig-Holstein question in the nineteenth century. According to Lord Palmerston, the British foreign secretary at the time: “The Schleswig-Holstein question is so complicated, only three men in Europe have ever understood it. One was Prince Albert, who is dead. The second was a German professor who became mad. I am the third and I have forgotten all about it.”

The allegations and counter allegations, the legalese, the obfuscations and obstructions... it is pretty clear that probably only the main protagonists in this drama have a grip on the detail, and maybe then not all of it. When big political arguments get “procedural”, the public tend to lose interest. When, during his six-hour evidence session to a Scottish parliamentary inquiry, Alex Salmond started talking about “sisting” (at least that’s what I thought he said), I fear he may have left his audience behind. Still, the stakes are high, as there is a chance that the sheer weight of allegations will push the first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, out of her job, and with her fall the end of the current dominance of the Scottish National Party at the May elections, and a setback for the cause of independence. So it matters. For that reason it may be worth the risk of going mad, and trying to see what is actually going on.

Put at its simplest, Alex Salmond feels that he is the victim of a conspiracy to end his career in public life, and that his successor as leader of the SNP and as first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, was at the centre of that. It’s not going too far to say he feels betrayed. In Salmond’s view, Sturgeon and her allies put in place a new harassment complaints procedure purely to trap him. Further, some of the women who accused him of misconduct were pushed into making criminal accusations and going to the police. Salmond thinks that Sturgeon knew all about this before she lets on, and that she said she would assist him in these matters informally, a promise he thinks she reneged on.

In any case Salmond was found not guilty of all 13 charges, and the judicial review he launched found that the Scottish government had acted unlawfully. Salmond’s allegations that Sturgeon and others broke the ministerial code and/or misled the Scottish parliament have prompted two current inquiries. One is by the MSPs; the other by an independent QC, James Hamilton, who Sturgeon referred herself to.

The pair have not spoken to each other in nearly three years, extraordinarily, and Salmond goes so far as to imply that Sturgeon would have happily seen him sent to prison, broken and disgraced. If so, it was not always her opinion. When she took over as party leader and first minister in November 2014, Sturgeon offered this paean of praise: “The personal debt of gratitude I owe Alex is immeasurable. He has been my friend, mentor and colleague for more than 20 years. Quite simply, I would not have been able to do what I have in politics without his constant advice, guidance and support through all these years. I can think of no greater privilege than to seek to lead the party I joined when I was just 16.”

Salmond implies that he’s a victim, and that if Sturgeon had resolved these allegations none of this trouble would have anyone’s. Her view is that “the ego of one man” risks destroying much of what the SNP (and she) has achieved. Hence that sense of mutual betrayal. This is more than understandable, because the pair were such close allies and firm friends during the long and often lonely struggle for Scottish independence, which may now be lost. It is hard to understand the scale of emotional investment the pair of them have in the cause, the tireless efforts of four decades. While the SNP carries all before it these days, it is not so long ago that the cause of Scottish nationhood was something of a minority pursuit, even an eccentricity. Both Salmond and Sturgeon are long-standing and passionate believers in restoring the sovereignty of Scotland lost in the Act of Union with England (and Wales) in 1707. When the SNP at last came to power at Holyrood in 2007 there was a certain sense of a historical circle being turned, though not yet quite completely. The independence referendum campaign that followed in 2014 was led by Salmond, but run by his then deputy Sturgeon. It almost succeeded, and before long there may be a second one, and a historic moment when Scotland becomes a nation again. It is something both figures have dedicated their lives to, and something they are now placing in jeopardy.

Sturgeon, for example, joined the SNP shortly before her seventeenth birthday, back in 1987. At the general election of that year a gifted young politician by the same of Alex Salmond was elected to the Commons for the SNP, and he was soon to become its leader, and an inspiration to Sturgeon. But he was a rarity. At that time the SNP was a marginal force with a handful of MPs, and, of course, no Scottish parliament or anything like it. Scotland was still owned by the Labour Party, and someone from Sturgeon’s working class background in Ayrshire who had political ambitions would have been expected to sign up to the Labour Party. When Nicola Ferguson Sturgeon came into the world on 19 July 1970, even the idea of a Scottish assembly was still a bit fanciful. Her father Robert (known as Robin) was an electrician, and mum Joan a dental nurse. Neither was especially political, or a nationalist, though that was to change when Nicola encouraged her mother to run for a seat on the council.

The personal debt of gratitude I owe Alex [Salmond] is immeasurable. He has been my friend, mentor and colleague for more than 20 years. Quite simply, I would not have been able to do what I have in politics without his constant advice, guidance and support through all these years

In those days in west central Scotland they mostly weighed the Labour votes rather than count them, and even the Tories enjoyed a bigger presence than the Scot Nats. Indeed, Sturgeon tells the story of how a well-meaning teacher at her school brought her a Labour membership application form just because she’d shown a precocious interest in current affairs. She rebelled a little at the patronising attitude, but if she had had an eye in a career in progressive politics the that would have been the sensible thing to do. Instead she fell in love with the nationalist cause, because, as the argument went at the time (and is revived again now) Labour’s weakness means the choice was between a Thatcher government or a Scottish government. Nicola Sturgeon joined the SNP “purely out of conviction”. She was thrilled that her home town of Irvine was mentioned in the lyrics of a famous Proclaimers’ hit, and the de-industrialisation of the country at the hands of an uncaring doctrinaire Conservative administration in London was bitterly resented. Mass unemployment, poverty, the poll tax... it is fair to say that Margaret Thatcher did more for the cause of Scottish independence than the entire SNP in those days, and it was she who propelled Sturgeon into nationalism. Something of the same might be said nowadays about Brexit and Johnson. For some the Scottish cause is romantic and cultural, almost mystical, as it seems to be for Salmond; for Sturgeon it is more practical and political, more of a means towards an end.

Sturgeon’s commitment to politics was near absolute, and seems to have grown out of an extreme bookishness. Her enthusiasm for reading, evident and genuine to this day, was evident from a very early age. Her mother recalls that “she was a quiet and studious child. She loved books from a very early age. She read before she went to school. Nicola was desperate to learn. She got quite frustrated, so we sat with her and she was easy to teach. Nicola would lift a newspaper at the age of four and try to read it.” Sturgeon adds that at her fifth birthday party, she actually hid under a table so she could get through another book rather than play with the other kids. (She wasn’t an only child – a sister arrived five years after her). “I wasn’t particularly outgoing, but then – I’m always slightly worried this sounds a wee bit overly grand – there was always just a sense I had something inside me.”

Her nationalism was also part inspired by one particular work, the novel Sunset Song by Lewis Grassic Gibbon, which speaks to the tough realities of rural Scottish life in the 1930s. As soon as she could she was standing for election to the national committee of the party’s youth wing, the Young Scottish Nationalists, and threw herself into a Youth for Salmond group to get him elected party leader, which he was in 1990. At university in Glasgow she spent a good deal of time trying to beat Labour in various student bodies and local elections, and failing. Yet she did not ever give up her party, hopeless as the cause was then. Even her chosen subject, law had a political aspect. She studied international law, including human rights and treaty law, and she also spent a good of time in law centres and courtrooms stopping poor families from being evicted. She wasn’t really cut out for a life of conveyancing, however.

Sturgeon was completely committed to Salmond’s leadership in the 1990s with its modernising agenda, moving away from some of the more fundamentalist instincts of the past – accepting devolution as a steeling stone towards independence rather than rejecting it outright or boycotting it. At that time it was thought on both sides of the debate that a Scottish assembly and executive, as was set up in 1999, would kill the SNP “stone dead”, which was great from Labour’s point of view and a calamity by some in the SNP, though not by Sturgeon and Salmond, who did quite well out of it.

When Salmond formed the first, minority, SNP administration in 2007 he made Sturgeon his health secretary, a post she mostly acquitted well, displaying that taste for hard work and effective presenting that she was later to become noted for. By then, after a brief interregnum when Salmond stepped down from the leadership, Sturgeon had risen to be deputy leader, and heir apparent. She had been planning to run for the leadership, but withdrew after Salmond indicated he would, after all, make a comeback. At that point she ruptured her friendship with a rival, Roseanne Cunningham, who she had been close to – but Sturgeon put party (and herself) first. After that, she and Salmond operated as almost a joint leadership team, and, from 2004 to 2007, before Salmond was back in the Scottish parliament, she was effectively the leader of the opposition, asking the questions of Labour’s first minister, Jack McConnell. While she couldn’t rival Salmond’s wit and debating skills, she did sometimes get the better of her much more experienced Labour opponent.

So devoted was Sturgeon to Salmond during these golden years for the SNP that she quietly ditched a lifelong commitment to unilateral nuclear disarmament, for the sake of party unity, and she even picked up Salmond’s habit of jabbing his head forward when speaking. With her motorbike helmet-style hairdo, Sturgeon often looks like she’s headbutting an imaginary opponent when she’s up on a podium, and with a few additional jigs of her bonce side to side when she gets animated she resembles nothing so much as a giant bobble-headed doll.

That said, Sturgeon has also spent the last few years, and especially as first minister, developing a distinctive style. Her bright outfits, often trouser suits, come from Totty Rocks, and are set off with very high heels (she is 5ft 4in). This is not footwear, as she once quipped, she couldn’t go dancing in. The first minister has a hairdresser and make-up artist, Julie McGuire, who also helps Sturgeon look like she means business. With Angela Merkel and Theresa May, Sturgeon was regarded for a time as one of the new breed of business-like female political leaders, clearing up the mess left behind by the boys.

Sturgeon, like the others, was also asked about not having children, and she later (in 2016) tweeted about her miscarriage at the age of 40: “By allowing my own experience to be reported I hope, perhaps ironically, that I might contribute in a small way to a future climate in which these matters are respected as entirely personal – rather than pored over and speculated as they are now.” It has not turned out like that, and Sturgeon continues to be the subject of gossip. Only a few days she had to dismiss the urban myths in these terms: “This sort of exotic double life that I’m supposedly leading is a damn sight more interesting than the actual life I’m leading. It does not have a scintilla of truth or basis in reality. It is just so completely off the wall.”

No doubt it is irritating to her that she has to spend time on this stuff and on her appearance in the way that the crumpled Salmond (also child-free) or Boris Johnson (not so much) never have to, but, ever the professional, she is game enough to go along with it. She once said that... but her care over her immaculate appearance suggests otherwise. If Scotland’s freedom means a few bunions, so be it.

She and Salmond had both served as SNP vice-convenors for publicity, and they learned a good deal from watching how Peter Mandelson and Tony Blair transformed Labour’s image. As they settled into power they decided they would run Scotland as if it was already an independent state, adding more and more trappings of a nationhood, such as having consulates in Edinburgh for the likes of Germany, France, Poland, Japan and Italy, though many are purely honorary. After her spell at health, Sturgeon was made minister for infrastructure and given a lead role in the 2014 independence campaign. After it failed, and Salmond resigned, he happily backed his protégée for the leadership, and she was elected unopposed. As first minister she has had to bring independence back, after the Brexit referendum offered a unique opportunity to reopen the “once in a generation” decision made in 2014. Conditions for victory have never been more propitious. You can understand, if this was the case, that Salmond might have expected his pupil to put the cause of independence and unity first. Sturgeon, maybe, saw Salmond and his behaviour as something of a threat not so much to her personally, but to that very goal of independence.

For the SNP and its leaders, 2007 was a turning point, for as Tony Blair later reflected, and Sturgeon and Salmond also knew full well, getting the SNP out would prove a lot harder than stopping them getting in. Though not for her country, an extended period of Tory-led government has helped the SNP keep its hold on power, turbocharged by Brexit. When Sturgeon told, or confirmed to, the then French ambassador Sylvie Bormann that she’d rather David Cameron than Ed Miliband won the 2015 election she was making a shrewd judgement (though Sturgeon denied it and made the unusual move of ordering a leak inquiry), and Cameron duly served up the 2016 referendum defeat. The SNP could claim, undeniably, that Scotland was being torn out of the EU against its wishes.

After almost 14 years of uninterrupted SNP rule, it is now only the SNP that can defeat the SNP; its splits now represent the most potent threat to independence. Had they won in 2014, things would have been very different. The current war between the two former long-term allies has that considerable back story attached to it, and it is a poignant one.

Yet, aligned as many of their political values and aims always were, Sturgeon was never some facsimile of Salmond. She is, as is well observed, more meticulous in presentation and preparation. Sturgeon’s daily Covid press conferences and weekly parliamentary question times are ample evidence that she can handle a brief pretty effectively. She has been less accomplished in her set-piece interviews over the years, notably with fellow Scots Andrew Neil and Andrew Marr, and particularly when she has to deal with economics, though it’s not entirely her fault that she doesn’t know what money an independent Scotland would be using – it’s a tricky business. Her main tactic is to admit that things are not perfect in the schools, say, or with vaccinations and use selected stats to prove they’re making progress, and say it’s better than in “the rest of the UK”, ie England. The broad fact is that the data shows that the Scottish experience was roughly the same as in the rest of the UK, but from Sturgeon’s cool, careful, articulate performances, contrasting with bumbling Boris, you’d never know the difference. When she has to admit error in her career, it has been precisely delimited. When she had to account for an outbreak of a “killer bug” in the hospitals and when she once made the blunder of defending a constituent guilty of fraud, the apologies were precisely demarcated and minimised.

Sturgeon is good on a platform, and answering questions, and she should put in a formidable show when she eventually says her piece. Yet there is a tendency to verbosity, to her which will mean her testimony to the inquiry may take even longer than Salmond’s did. You can imagine someone on the inquiry asking Sturgeon the time and her coming back with: “Well, let me say first of all that time is, and always had been, always will be, a matter of great importance, both here in Scotland and around the world. No one understands better than I do how important the right time can be, and there are many ways of telling it. Now I’m not going to pretend that I’m the only person who can tell you the time, nor should I be, but what I will say is that there’s no evidence that it’s any different in the rest of the UK, and that’s an answer I am prepared to stand by.”

When Sturgeon told, or confirmed to, the then French ambassador Sylvie Bormann that she’d rather David Cameron than Ed Miliband won the 2015 election she was making a shrewd judgement, and Cameron duly served up the 2016 referendum defeat. The SNP could claim, undeniably, that Scotland was being torn out of the EU against its wishes

As well as a talent for buying time with verbiage, she has a trained lawyer’s eye for detail, and the get-out clause. When she appears before the MSPs it will be as a lawyer answering questions from politicians, not the other way around, and she will be very well briefed. She works hard at everything, and is something of a control freak. Sturgeon is as smart as he is at turning an argument, and at adding the facts to back it up. She tends not to take too many prisoners; few will forget the orgasmic joy she displayed on election night in 2019 when she watched Jo Swinson, the Lib Dem leader lose her seat – after the SNP supported her in calling for an early general election and dissolving parliament. Having Boris Johnson as the quintessential English bogeyman installed in No 10 suited the SNP nicely, though she might not have admitted that to Swinson.

The downside to the Sturgeon style, allowing for a certain amount of sexism in the way she is reported on, is a reputation for being what they call in Scotland “a nippy sweetie”, meaning someone who is annoyingly argumentative. She seems to have picked it up in her time in Glasgow when she was out campaigning in solid Labour ex-shipbuilding areas. Sturgeon herself explains it like this: “Unconsciously and unknowingly I started to behave in a way that was about conforming and fitting in with the people that I was surrounded by. That was reflected I guess in how I chose to dress as a young woman in politics, in how I behaved. In politics, if you are trying to fit in with how the men around you are behaving then that means you become adversarial and, dare I say it, aggressive in how you pursue and articulate your arguments.

“But here’s the real nub, and here’s the trap for women. You find yourself emulating the traits that in men are seen as strengths. Then you quickly realise that in women they are not seen as strengths. So the male politician who’s very assertive, aggressive and adversarial is a great, strong leader. A woman is bossy and strident – a nippy sweetie as they used to call me.”

This gives a significant clue to what might have been going through Sturgeon’s head as she learned more about the accusations about Salmond. For much of what has driven her in public life is what we would now call “identity politics”. From her very earliest time in politics she championed feminism and LGBT+ equality, and was the first Scottish leader to be a honorary warden at the nation’s main Pride event. Just as Scottish nationalism was an unpopular crusade in the 1980s and 1990s, so too was equal human rights for gay, lesbian and trans people. Today, her government is pioneering trans rights legislation that has attracted much criticism in her own party, including from Joanna Cherry MP, now sacked form the party’s front bench in Westminster. It is one of a number of issues where Sturgeon is seeing her party divide, the others being whether to use guerrilla tactics and an unofficial referendum to pursue independence; how radical the economic policy should be; and the treatment of Salmond himself. Like most parties in power for a long time with a lack of effective external opposition, the SNP is just starting to bicker. Ms Sturgeon has some control over the party machine because the SNP chief executive, Peter Murrell, happens to be married to her, but she longer enjoys such solid backing in the SNP National Executive Committee, recently described as “a zoo”. But Sturgeon is not for turning on her interpretation of trans rights.

The same principled stance applies to women’s rights, and there is no conflict with trans rights in Sturgeon’s world view. The #MeToo movement was gaining much momentum when the rumours or news about Salmond’s accusers was emerging (the date Sturgeon knew being much contested), and for someone with Sturgeon’s feminist sensibilities, and political nous, to have such a scandal engulf the SNP, the chance of independence and indeed her premiership must have been an appalling prospect in 2017 and 2018. Sturgeon has a slightly reserved, even aloof air to her publicly, partly born out of shyness; but there are many accounts of her empathy towards troubled people in private settings, and there’s no reason to doubt that she was distressed about what she was hearing about her old friend. Speaking in general terms she recently said of #MeToo: “It has made a lot of people, me included, reassess things that at the time you just put up with. You know, guys kind of touching you in slightly uncomfortable ways, and the leering.” Sexism and misogyny is “not completely gone … it just manifests itself in different ways”. She would have wished to do right by the women, quite naturally, but also right by her party and country. Her old loyalty to Salmond, authentic as it had been, had to be suborned to what she has called the “transcendent” cause of nationhood.

Scotland is not a one-party state, nor is it a one-woman town. It is, though, a relatively small country and its politics have been dominated for almost two decades by one party, and two pre-eminent personalities. The opposition from the other parties is weak to non-existent (Scottish Labour has just appointed a fifth leader in seven years). The machinery of Scottish governance is also mostly relatively new. It has meant a number of things. First, that semi-independent political and civic institutions, such as the civil service, the Scottish parliamentary authorities and the police have become habituated to SNP rule. As in Whitehall in the Thatcher-Major years, or again under New Labour, long periods of single-party administration inevitably lead to recruitment and promotion of staff on the principle of “one of us”, and officials tend to start think more like the only politicians they’ve served. That, by the way, is evidently not true of Scotland’s venerable independent judiciary.

You find yourself emulating the traits that in men are seen as strengths. Then you quickly realise that in women they are not seen as strengths. So the male politician who’s very assertive, aggressive and adversarial is a great, strong leader. A woman is bossy and strident – a nippy sweetie as they used to call me

It is not as simple as what Salmond calls a “failure of leadership”; it is an occupational democratic hazard. Scottish politics is very lop-sided, just as it used to be under Labour, before that hegemony eventually became undone by its own complacency and neglect. There’s no God-given reason why the SNP won’t go the same way.

Second, the opposition to the first minister has moved from Labour and the Tories to inside the SNP, with Salmond as an awkward figurehead for it, and it is an unfamiliar feeling for a party that has not suffered too badly from factionalism as it has enjoyed its successes. The fact that the SNP leader and the SNP chief executive are married also can’t be seen as ideal from an administrative point of view. Absurd arguments during the Salmond case about whether Murrell was parked in the front room in a party, government or hybrid capacity highlight the problem.

If Sturgeon is ousted, or leaves office for some other reason, then there is no clear successor to her, and suddenly the party will look terribly exposed just as the May elections are looming. (Much depends on how rapidly the two inquiries report.) Whatever the outcome of these inquiries, though, Salmond is going to stick around, with not very much to do with his life, and will no doubt be a disruptive influence for some time to come. Third, if Sturgeon does come through this test, wounded but not conquered, appropriate apologies briskly issued, then she really will be a stiletto-wearing, fuscia-jacketed colossus, bestriding Holyrood and set to take Scotland out of its 300-year union with England and onto a seat at the European table as leader of an equal sovereign state. Not bad for a nippy sweetie.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

79Comments