Earliest evidence of Maya calendar found inside Guatemalan pyramid

Academics now believe other sites will find examples from even earlier than 200 BC, Sam Hancock writes

Mural fragments from between 200 and 300 BC with remnants of a “Seven Deer” glyph on them have been found inside the ruins of a pyramid in Guatemala.

The discovery marks the earliest-known use of the Maya calendar, an historical system created from movements of the sun, moon and planets which was based on a ritual cycle of 260 named days.

Until now, the earliest definitive Maya calendar notation dated to the first century BC.

The fragments were found at the San Bartolo archaeological site in the jungles of northern Guatemala, which gained prominence following the 2001 discovery of a buried chamber with elaborate and colourful murals dating back to around 100 BC depicting Maya ceremonial and mythological scenes.

Pieces with the Seven Deer glyph – one of the calendar’s 260 named days – were unearthed inside the same Las Pinturas pyramid where the still-intact later murals were found 21 years ago.

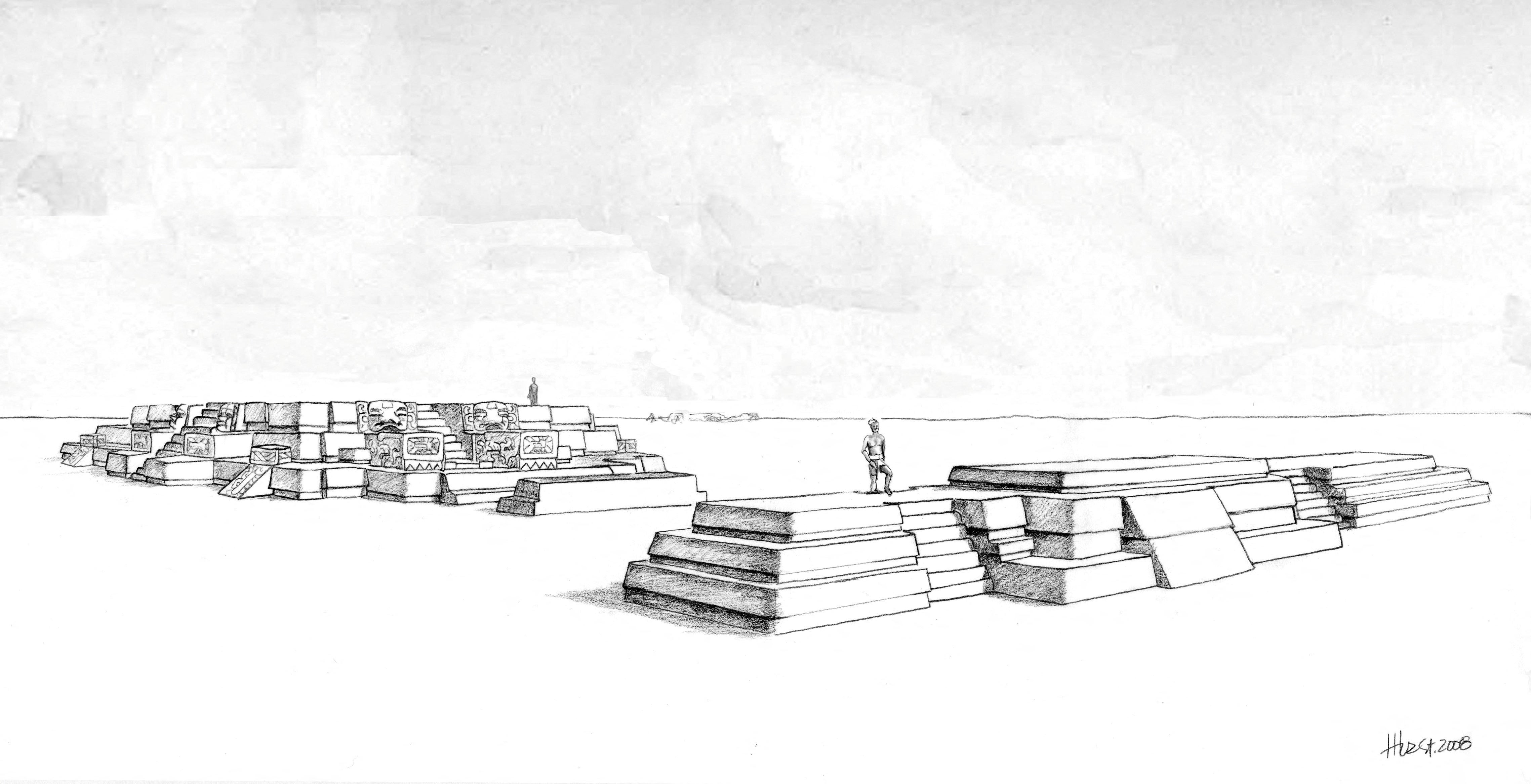

The Maya civilisation often built what started out as modest-sized temples, then constructed ever-larger versions one on top of the other, meaning pyramids – like the one being excavated – eventually reached around 100ft (30m) tall.

Researchers said the Seven Deer glyph that was found consisted of the ancient Maya writing for the number seven over the outline of a deer’s head.

David Stuart, lead author of the research, which was published in the journal Science Advances, described the fragments as “two small pieces of white plaster that would fit in your hand, that were once attached to a stone wall”.

Mr Stuart, a professor of Mesoamerican art and writing at the University of Texas, continued: “The wall was intentionally destroyed by the ancient Maya when they were rebuilding their ceremonial spaces – it eventually grew into a pyramid.

“The two pieces fit together and have black painted calligraphy, opening with the date ‘7 Deer’. The rest is hard to read.”

“The paintings from this phase are all badly fragmented, unlike any from the later, more famous chamber,” he added.

The Maya calendar’s 260 days was one of several inter-related Mayan systems of reckoning time, which also included a solar year of 365 days, a larger system called the “Long Count” and a lunar system.

A writing system was also developed in the culture, which encompassed 800 glyphs – the earliest examples of which were also found at the San Bartolo site.

San Bartolo was a regional centre during the Maya Preclassic period – spanning from around 400 BC to 250 AD – which heralded the way for the subsequent Classic period, known for the creation of cities including Tikal in Guatemala, Palenque in Mexico and Copan in Honduras.

Around 7,000 mural fragments, some as small as a fingernail and others up to 8-by-16ichs (20-by-40cm), have been found at San Bartolo, amounting to what anthropology professor and study co-author Heather Hurst, of Skidmore College in New York, called “a giant jigsaw puzzle”.

The latest research, which saw experts examine the Seven Deer glyph, and other notations from as many as 11 San Bartolo mural fragments, suggests there were “mature” artistic and writing conventions in the region at the time – and that the calendar may have already been in use for years, the academics noted.

“Other sites will likely find other examples, perhaps [from] even earlier,” Ms Hurst said.

Additional reporting by Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments