U-boat wargamers: The unsung women who changed the course of WWII

As their story comes to light in a new docudrama, James Rampton looks at this extraordinary group of strategists who helped win the Battle of the Atlantic

This is the story of the greatest war heroes you’ve never heard of. It is an astounding and scandalously overlooked tale about a top-secret group of women who played a pivotal role in the Allied victory in the Second World War. Instrumental in helping Great Britain win the Battle of the Atlantic, they are the unsung heroes who set us on the path to vanquishing the Nazis.

These women were some of the most brilliant wargamers of their – or any other – generation, but their significance has largely been forgotten. On the 80th anniversary of their operation, the story of these neglected heroes is finally being recounted. And what a story it is.

At the start of the war, the German admiral Karl Doenitz’s seemingly invincible wolf pack of U-boats posed a clear and present danger to the very survival of Britain. The enormous threat they represented was evident from the outset of hostilities. On 3 September 1939, just two days after war was declared, a U-boat sank the passenger liner SS Athenia in the Western Approaches. One hundred and seventeen people, including refugee children, lost their lives. A truly shocking event, it was declared a war crime.

Worse was to come, though. On 14 October 1939, under the command of the German ace Gunther Prien, a U-boat infiltrated Scapa Flow, the base of the British Home Fleet. The submarine torpedoed the battleship HMS Royal Oak. Of the 1,400 servicemen on board, 833 perished.

The U-boats are all but invisible. They get inside the convoy, going up and down the lanes, picking out the biggest ships and sinking them almost at random

The U-boat had penetrated the one place where British battleships were supposed to be safe. It was a deeply traumatic incident for the Royal Navy. As historian Dr Craig Symonds puts it: “The fact that Gunther Prien could take a U-boat into the heart of the British Home Fleet, sink a battleship and get away again was humiliating.” It was an immediate propaganda victory for the Nazis. Prien was hailed as a national hero and given a parade through Berlin.

That was not the end of the British suffering. On 18 October 1940, Doenitz launched an attack on an Allied convoy codenamed SC7. Evading the sonar on the British ships, the wolf pack proceeded to carry out a dreadful massacre. Of the 35 merchant ships in the convoy, 20 were sunk. The ace Otto Kretschmer alone downed seven of them.

Symonds details what took place on that fateful day. “The U-boats are all but invisible. They get inside the convoy, going up and down the lanes, picking out the biggest ships and sinking them almost at random, as if it was some kind of 20th-century video game.”

Intoxicated by the scent of victory, Doenitz promised a Knight’s Cross to any ace who managed to sink 100,000 tons of Allied supplies. It was a deadly period for British seamen. The historian Dr Tessa Dunlop says: “This is what Germans refer to as their ‘first happy time’. While they may talk in terms of tonnages of cargo at the bottom of the sea, we know that also means a lot of lives.”

By 1943, Britain was down to its last few weeks of supplies and on the brink of capitulation. Christian Lamb, who was a member of the Women’s Royal Navy Service (otherwise known as the Wrens) from 1939 to 1945, recalls, “It was a very severe moment in the war, the lowest point where we were in danger of starvation.”

As the U-boats devastated the Atlantic convoys, an Allied defeat to the Nazis appeared all but inevitable. There appeared to be no way of countering these lethal attacks. According to historian Dr Marc Milner: “All of a sudden – bam – you get this attack by wolf packs that looks like it’s going to overwhelm the convoy system. It does surprise the British because they don’t have an answer. The German tactics are new, and the British are all scratching their heads – ‘What do we do now?”

Winston Churchill later admitted that the early German success in the Battle of the Atlantic was the sole element of the conflict that ever caused him to lose sleep. He declared: “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

The navy was at a complete loss about how to combat this indomitable foe. In desperation, the Admiralty asked the retired wargamer Captain Gilbert Roberts – who had been invalided out of the Royal Navy with TB and was now wearily training the Home Guard – to convene a highly-confidential team known as the Western Approaches Tactical Unit (WATU). His mission was to come up with a plan to outfox the U-boats and turn the tide of the war.

At the time, the women signed the Official Secrets Act so they couldn’t talk about their involvement. After the war, they just carried on with their lives

Roberts was anxious to find a team as quickly as possible, but the Navy couldn’t spare any men. So instead he called on a group of Wrens to wargame the tactics that would outmanoeuvre the U-boats. He handpicked a team comprising 66 outstandingly intelligent women mathematicians, statisticians and accountants. Some of them were as young as 17. The group was led by 21-year-old Jean Laidlaw, an immensely gifted strategist and one of Britain’s first female chartered accountants.

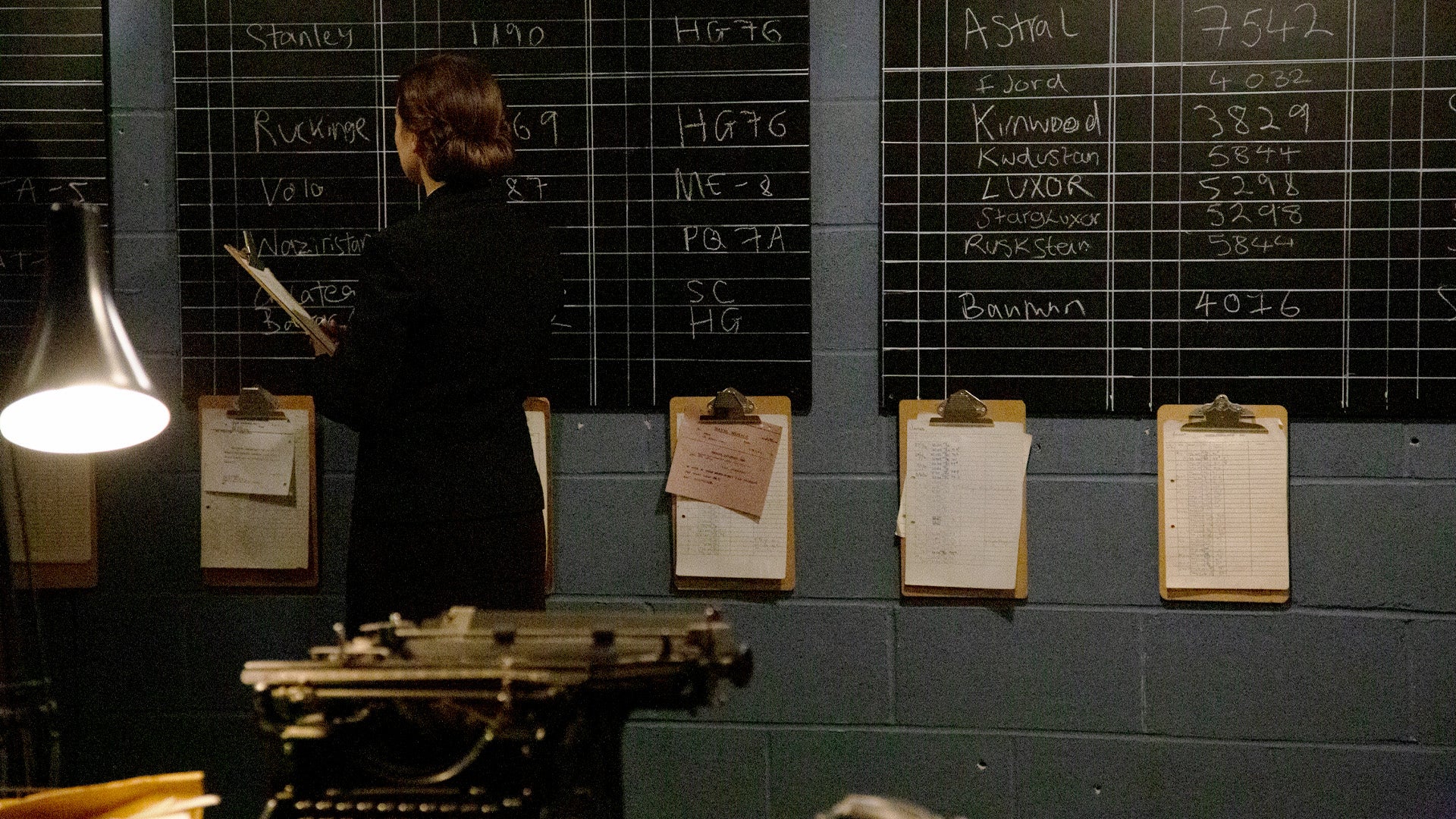

Based at the Western Approaches Command Centre at Derby House in Liverpool, this hugely talented group of women accomplished what the top brass at the Admiralty had signally failed to do. In just six weeks, this crack team decoded Donitz’s tactics and devised a method by which the Royal Navy’s destroyers crept into the wolf packs and sunk the U-boats one by one. Without these astonishing efforts, Britain would almost certainly have been starved into surrender.

The hitherto unheralded exploits of the WATU are now the subject of U-Boat War Gamers, a gripping six-part docudrama that stars Molly Vevers as Laidlaw and Andrew Havill as Roberts.

Vevers says the fact this episode from the war has been never been related before makes it all the more riveting. “This is an untold story from a period of time that we otherwise know so much about and studied at school. We all know about World War Two, but I had never heard of this story. So when I found out there was this group of young women who were so integral to us ultimately winning the war, I was fascinated and just wanted to find out more.”

The actor goes on to explain why this tale has remained hidden for so long. “At the time, the women signed the Official Secrets Act so they couldn’t talk about their involvement. After the war, they just carried on with their lives. But now is the time to get their story out there. They deserve that recognition.”

Another reason why this story has been passed over until now is because the women from WATU manifested that quintessential British characteristic: modesty.

Alexandra Bota, the producer of U-Boat War Gamers, which begins on Sky History at 9pm on Tuesday, says: “These women never really spoke about their wartime service to their family and friends. They were part of that generation that didn’t really feel that they needed to speak about it.

“There was simply a job that had to be done and the women didn’t feel the need to be glorified or receive recognition afterwards. So the reason we weren’t privy to the story before is because that generation just wanted to do their bit and not brag about it afterwards.”

Very legitimate security considerations may also have lain behind the women’s reluctance to boast about their achievements post-1945. “We have to remember that immediately after the Second World War, there was the Cold War,” Bota reflects. “The women from the wargaming unit were restricted in what they could talk about because they were involved in developing tactics that may have been very relevant in the conflict that happened directly after the war.”

What they were using was so rudimentary. You’re talking about a grid on the floor with straight lines, chalk, string and a few model boats

But the story is out there at last, and now is a very good moment to be telling it. “We’re in a different time in terms of women’s role in society and feminism,” Vevers notes. “These women should be celebrated, and that’s why their story is being told now.”

The Wrens were headed by the formidable former suffragette leader Dame Vera Laughton Mathews. At first, she presided over a group of women charged with simply making tea and driving offices around London. At the start of the war, Wrens weren’t even allowed on naval warships because seamen thought it brought them bad luck.

But Laughton Mathews set about changing those outdated attitudes. “She can recognise that Britain hasn’t yet fully appreciated what women can do for the war effort,” says historian Paul Strong. “Give them a chance and they can show what they can do.”

They certainly did that. The women had an immediate effect when they arrived at WATU. The fact these women were fresh to this apparently intractable problem meant that they came at it from an entirely new direction. Intuitive problem solvers, they could discern tactics that were invisible to their more regimented male predecessors.

“Because the men were away on active service, Roberts couldn’t use them,” Havill muses. “But calling on these young women was the best thing that could have happened because they saw things that the men who had been trained to think in very straight lines wouldn’t have come up with. They wouldn’t have been as instinctive in that way.”

A major challenge the women from WATU faced was handling their unexpected position of power. The historian Professor Alexandra Richie says: “They were all of a sudden put into roles of great responsibility that women had never had before.”

Derby House was undoubtedly an intimidating, almost exclusively male environment for the young women. When they first came to Liverpool, they were treated very dismissively by the male hierarchy. “The Wrens were not rated at all by the Admiralty,” says Havill. “They were put in a basement room downstairs with bits of string and told, ‘Don’t come to us for any help. Just get on with it.’ It’s a great underdog story.”

Vevers takes up the theme. “To begin with, there was a lot of friction with the men who were the leaders of the Royal Navy. They looked down their noses at these very young women. So it’s a very satisfying arc where the women ended up coming up with tactics that really turned things around.”

She adds: “Wartime is quite a leveller, isn’t it? During the war, women became more equal out of necessity, but ultimately that was a positive for society.”

The women at WATU also had the daunting task of passing on their revolutionary naval tactics to very senior officers, but they took it in their stride. “If I had ever been fortunate enough to meet Jean Laidlaw,” Bota ventures, “the first question I would have asked her would have been: ‘How did you find the strength to even address some of these high-ranking officers?’

“These weren’t just petty officers; these were high-ranking commanders who essentially would be in charge of a warship that would accompany convoys across the Atlantic. So Laidlaw had the courage to teach these men how to conduct themselves in a field that they had trained for their entire careers. What she did was absolutely incredible.”

The tactics the women invented at WATU were truly groundbreaking. They conceived the Step Aside, an avoidance movement that continued to be taught in Royal Naval colleges up until 2017. But their most celebrated strategic manoeuvre was the Raspberry. It was so named by Laidlaw who saw it as blowing a raspberry at Adolf Hitler.

Bota outlines the details. “The women tried to put themselves into the shoes of the U-boat commanders and identify how they were sneaking into the middle of the convoy and firing at close range. Laidlaw came up with the idea of Raspberry, in which the British battleships performed triangular sweeps of the ocean with Asdic [a British form of sonar]. It was like a fish net. If a U-boat was trying to escape from underneath the convoys, the British ships would ping it with Asdic and then fire depth charges at it.” This tactic proved very successful and transformed Allied fortunes.

The women tried to put themselves into the shoes of the U-boat commanders and identify how they were sneaking into the middle of the convoy and firing at close range

The fact that the resources available to the women were so basic makes their accomplishments all the more extraordinary. “It wasn’t as if they had huge computers to work it all out,” says Havill. “What they were using was so rudimentary. You’re talking about a grid on the floor with straight lines, chalk, string and a few model boats. They were analysing enormous amounts of data and reports of previous U-boat attacks. The way they made connections and found solutions was extraordinary. I still can’t get my head around it!”

The women were exceedingly devoted to their work, too. “They were so committed,” Vevers says. “It wasn’t a nine-to-five job. They would stay up all night because an essential part of a war game is repeating a scenario again and again. They wouldn’t sleep and they’d miss meals because they were so dedicated to solving the problem.”

Vevers considers what audiences might learn from U-Boat War Gamers. “This story has not been told before, so what I hope people will take away from the series is just the knowledge that it happened. This was a huge part of World War Two history. Everybody should know the story of WATU.”

Havill also expresses the hope that the series will help viewers understand the immense contribution the Wrens made to the Allied victory. “It was crucial to the outcome of the war. Seventy per cent of our food back then was imported. When those supplies are being decimated by U-boats, it’s a disaster for an island nation.

“The amount of tonnage that was lost was eye-watering. It’s almost inconceivable, but over an 18-month period, we lost 8 million tons of provisions. But these women stopped those losses and changed the course of the war. When they finished and the U-boats were no longer a problem, D-Day wasn’t that far off. I don’t know that D-Day could have happened if the women from WATU hadn’t solved the U-boat problem.”

Bota chimes in: “I hope people appreciate that some of the liberties we have today are down to that generation that had to sacrifice their own liberty for six years in order the deliver the Allies their victory and save us from the Third Reich.”

What’s the lesson of this story, then? “Always listen to women!”, says Vevers.

Bota agrees, declaring that a statue dedicated to Jean Laidlaw should be erected forthwith. “It should be in front of Derby House in Liverpool. And the plaque underneath it should read, ‘To the unsung woman who helped us win the war’.”

‘U-Boat War Gamers’ starts on Sky History at 9pm on Tuesday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks