Petty squabbles and strategic differences threaten to undermine Nato’s united front over Ukraine

Turkey is holding out over giving Sweden membership, while any pathway for Kyiv to join the alliance is still to be mapped out, writes Borzou Daragahi. And the issue of what to do about China – another major player in the Ukraine crisis – is a long-term concern

At a meeting of Nato defence ministers in Brussels, Nato’s secretary-general, Jens Stoltenberg, said that it is a “critical time” for the war in Ukraine as Kyiv begins its counteroffensive. The same could be said of the alliance itself as it seeks eastward expansion and plots its global role.

The Western military alliance that has been strengthened by the united front put in support of Ukraine’s fight against Russian invasion – but now finds itself facing a series of challenges sparked by a war that could fray that unity.

As Nato defence ministers gather in Brussels for the meeting on Thursday and Friday, ahead of the annual alliance summit in Vilnius next month, the most immediate and high-profile obstacle is the simplest to resolve: the resistance by Turkey and Hungary in embracing Sweden as a member. Though a distraction, it underscores persistent squabbling among some Nato members over how wholeheartedly to back Ukraine and to what extent Russia – led by President Vladimir Putin – is seen as an existential threat.

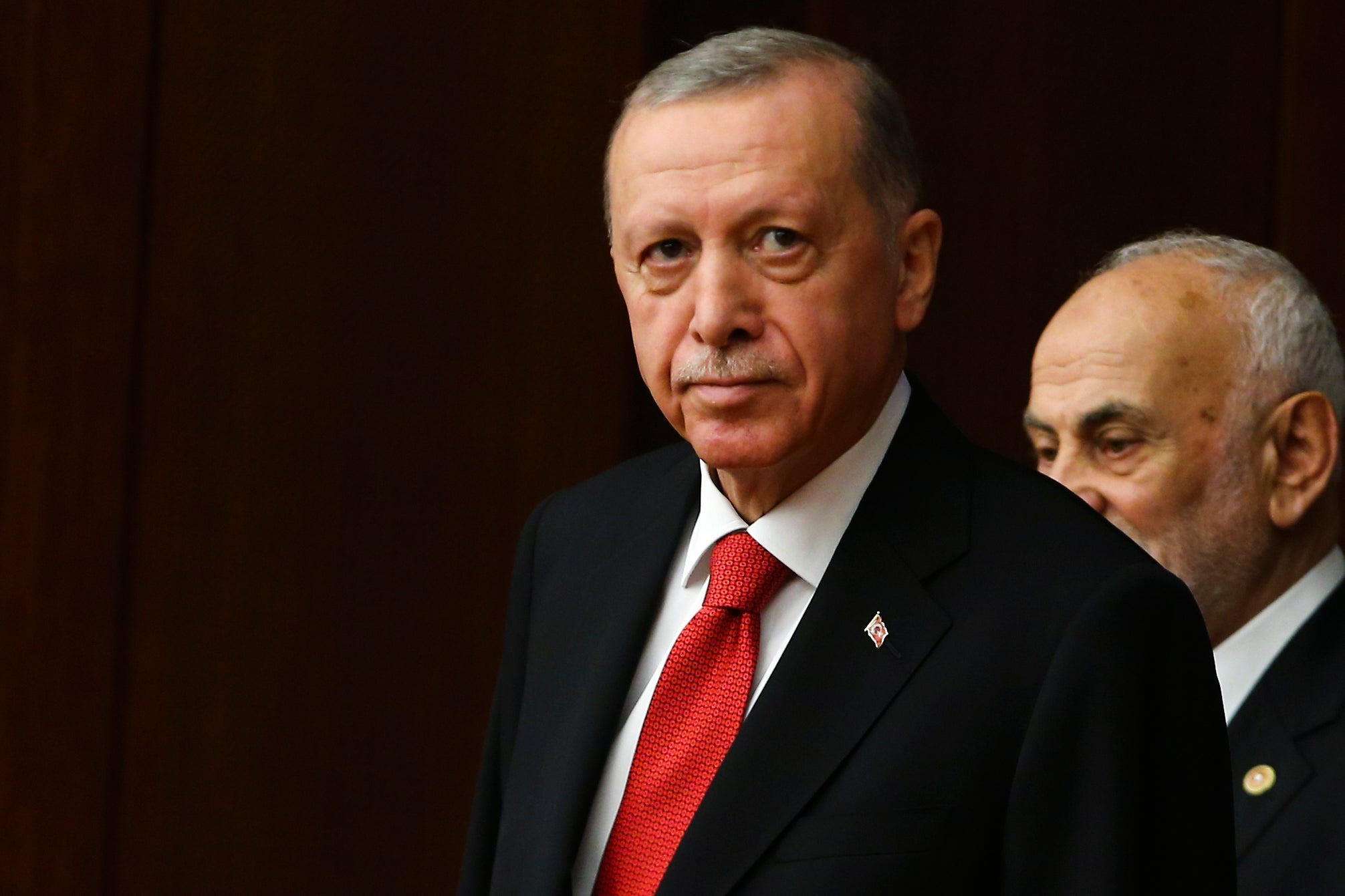

Both Turkey and Hungary say that they are sceptical about allowing Sweden into the alliance as part of an effort to confront Russia. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan demands Sweden do more to halt the activities of Kurdish militant groups active in the country and has been vocal over his reticence as talks continue. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban wants Stockholm to tone down criticism of his nation’s human rights record. Both are also likely are seeking further concessions from other alliance members.

However, experts say, both Budapest and Ankara are seeking other concessions that can easily be granted. Turkey wants the US to sell its late-model F-16s to upgrade its air force. Hungary wants European Union members to ease up on the pressure to reform. The fact that Finland, who applied for membership at the same time as Sweden, has already been accepted, shows that the barriers are not insurmountable.

“They are leveraging their veto rights to gain concessions in different fields,” says Bruno Lété, a researcher and scholar at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a European think tank. “I am fairly confident that this will be solved.”

It is an unwanted wrinkle, with the question of Sweden’s accession underscoring the continued double game that some Nato members play with Russia. Turkey and Hungary have increased rather than halted energy deals with Russia, and there are also strong voices in the United States – including Donald Trump’s – and in France that are openly hostile to supporting Ukraine. If the war drags on until the 2024 USS presidential election, the voices could get louder. A poll released by Ipsos this week suggested American that support for Ukraine could dip as the 16-month invasion continues.

“Opinions might shift as the Ukrainian offensive unfolds, the story rises in prominence in American news coverage, and Americans reexamine their attitudes about the war,” said Chris Jackson, senior vice president at Ipsos, in a note.

An even more potentially explosive dilemma faces Nato on whether, and how quickly, to allow Ukraine to enter the alliance, as it has requested repeatedly. Eastern European and Baltic countries are in favour of welcoming Ukraine while some Western nations are more reticent. The US political establishment is divided on the issue.

“The moment it gets real there will be real resistance,” says Yoruk Isik, a geopolitical analyst based between Istanbul and Kyiv. “Ukraine wants it. Poland wants Ukraine. But Germany and France will be totally against it.”

For now, a compromise at Vilnius appears likely, with Ukraine granted a status that would allow it to call for emergency Nato meetings if it is not a full-fledged member. Some analysts in Ukraine and outside have described an “Israeli model” where Nato would hand Ukraine all the weapons and training it needs – alongside some security guarantees – without needing to lay out the full path to membership.

“We will arm Ukraine to the teeth and transfer the advanced technology that itself needs to defend itself,” says Lété. “It’s already a partner, and it’s slowly but surely integrating and getting Nato training programmes and equipment.”

Stoltenberg has been clear that Ukraine belongs in Nato, but the way that happens is clearly not going to be solved by July, as Ukraine might wish it. Although Kyiv has seemingly come to accept that things won’t move as quickly as they want.

"Nato is being overwhelmed with multiple challenges at the same time," says Amanda Paul, an analyst at the Brussels-based European Policy Centre. "But they need to give Ukraine a credible road map for membership, and that needs to happen in parallel with security guarantees If they don’t Ukraine will remain a target of Russia. And it’s not just about Ukraine it’s about European security."

In the longer term, a third question looms – what role the alliance should play in addressing the rise of China, and whether its moves on Nato expansion and backing for Ukraine will prompt Beijing to increase its support for Russia and further complicate the war effort.

“China has been catapulted to the forefront of the Nato agenda,” says Lété. “China could also potentially become the most divisive issue for Nato.”

The US increasingly sees confronting Beijing’s ambitions as a far graver long-term threat than Russia, and has sought to press Nato into its efforts. Recently France vetoed an initiative to open a Nato office in Japan as a provocation. French President Emmanuel Macron has been outspoken in calling on Europe to avoid confrontation with China.

“Europeans don’t want another Russia-like scenario,” says Isik. “Russians have gone so off the rails. But China continues to behave diplomatically. Americans will push Nato toward the Asia Pacific. European allies will do their best to slow this down. They already have enough on their plate with the Ukrainian situation. There is no capacity to deal with China right now.”

Other than the UK, Nato’s European members also do not have as much invested historically or geopolitically in the Pacific. There are worries that if Nato joins the American effort against China, Beijing could respond by increasing its material support for Russia’s war effort.

“We also see how China and Russia are drawing closer together,” Stoltenberg said. “China is not our adversary, but it is challenging our security, our interests and our values.”

But continental Nato member states may end up having no choice but to join in an effort to confront China. Even as European member states say that Nato has no mandate beyond European security, China has already bought into key infrastructure, including seaports and telecommunications networks, in both Nato and non-Nato European states. Over 12 years or so, it has poured a billion dollars a year on average into the western Balkans, including Nato members Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia. It has been accused of using its investments in civilian infrastructure to engage in espionage, infiltration and disinformation.

“China is already here,” says Lété. “It has become an unavoidable factor in European security. It automatically becomes a concern for Europe because we need to defend ourselves from China at our borders.”

The challenges vexing Nato come at a time when persistent questions about the relevance of the alliance have been brushed aside by Putin’s invasion. According to a survey conducted in November, 70 per cent of citizens of Nato countries would vote to remain if the issue were put to a referendum, up from 62 per cent a year before. Only 11 per cent would vote to leave.

That helps ensure that the alliance can concentrate on the war in Ukraine, and the fallout that brings. But the alliance cannot afford to let the squabbles that come with some of the bigger issues around the invasion to crack what needs to be a united front.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments