Who owns space? Well it depends who gets there first

If Donald Trump, Nasa and Elon Musk get their way, the US will become the gatekeeper to the moon, asteroids and other celestial bodies. We must revolt before it’s too late, writes Andy Martin

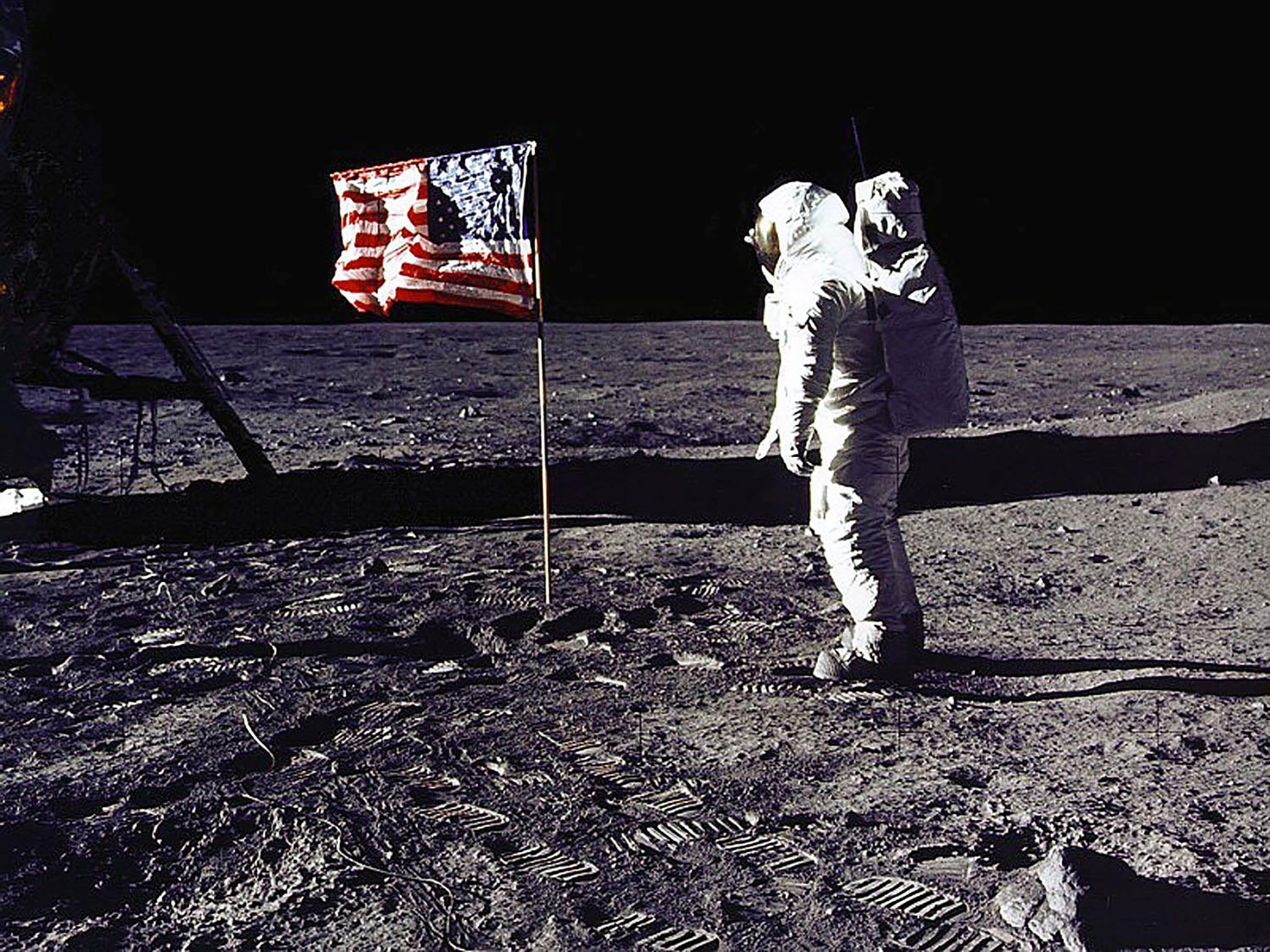

When conspiracy theorists examine the first moon landing with a sceptical eye, they look at the flag and note that it appears to be flapping in the wind. “Ah ha!” they squawk. “But there is no wind on the moon, therefore the whole thing was a fake and was being filmed on a Hollywood set somewhere, presumably equipped with a wind machine.”

But, of course, the flag is behaving the way flags behave on the moon or elsewhere when they are being manoeuvred into position. And the crucial point that the conspiracy theorists miss, which is staring them right in the face, is that this is an American flag that is being planted on the moon. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were doing exactly what Captain Cook did in Botany Bay and Columbus before him: sticking a flag in the earth and thereby – implicitly in the case of Apollo 11 – laying claim to ownership of the territory.

Except that in this case it wasn’t earth, because it was the surface of the moon. It was, quite literally, out of this world. The scramble for outer space began there. And it is continuing apace. It’s not Star Wars – not yet. But the carve-up of great chunks of extraterrestrial real estate is happening right now. Jean-Jacques Rousseau said inequality originated the day someone drew a line around a small patch of earth and said: “This is mine!” Now those lines are being drawn on other planets and moons and asteroids. Dmitry Rogozin, head of the Russian space corporation Roscosmos, recently asserted: “Venus is a Russian planet.” Meanwhile the United States is determined to brand its name onto everything else spinning around the solar system.

There is a fundamental principle at work here. It is best summed up in the infantile expression, “bags I!” If we can get our hands – or even remotely controlled robots – on it first, then it’s ours. The Latin version is: terra nullius – it’s nobody’s land. No one lives there. Which was the lie perpetrated about Australia and recycled again and again by rampant imperialists the world over. In this case there really is no one out there, unless you count bacteria. But soon there will be. And the squabbling over who owns what has already started. The answer would appear to be quite simple: “We do!” Nationalism is not only international but interplanetary. Colonialism never really went away, it has simply got rockets attached to it and boldly gone where no one has gone before. And the great motivation, as ever, is that there’s gold in them thar hills, even when they’re millions of miles away. El Dorado may yet be found, possibly on the moons of Mars or Saturn.

An article published this week in Science, “US Policy Puts the Safe Development of Space at Risk”, argues that America is blasting its America First policy into outer space. Science is the highly respected, peer-reviewed journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and publishes not only scientific research but also opinion on science policy. The measured but hard-hitting article has two authors: one an astronomer, Aaron Boley, the other a political scientist, Michael Byers, both at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. In August they were behind the “International Open Letter on Space Mining” that gained over 100 signatories including three Nobel laureates and called on the UN to establish a new multilateral framework for space mining.

“Powerful countries have always sought to shape the international system in their favour,” Byers tells me. “The US was once a founding member of the UN. The current US administration has decided that it doesn’t want to subscribe to the multilateral approach.” Whether on this or any other planet.

In April of this year Donald Trump signed an executive order saying that commercial space mining is legitimate. In September, Nasa announced that it is putting out to tender a plan to mine “regolith” on the moon, its heterogeneous surface layer. There is talk of mining Helium-3, which could be the solution to nuclear fusion, and hydrogen and oxygen, useful for the purpose of concocting water. But whether or not moon dust turns out to be valuable, the point is to establish a precedent: if we have the ability to extract pieces of extraterrestrial territory, then we will, regardless of anyone else. And will continue to do so in the future.

Byers says that the US administration “is trying to exert pressure on its traditional allies to go along with its preferred approach to space law”. America is trying to impose the so-called Artemis Accords on other nations, which would allow commercial space mining subject only to national – not multinational – regulation. “Negotiations” are under way, but the reality is if you don’t sign up to the Artemis Accords then you don’t get to participate in the any of the space programmes controlled by Nasa.

“It’s an interpretation of law,” says Byers. “But it is a powerplay.” If the US “interpretation” is accepted, then the US will become, as Byers and Boley argue in their article, “the de facto gatekeeper to the moon, asteroids and other celestial bodies”. They say that since acquiescence is often treated as consent in international law, then other nations need to start getting het up about this, right now, and protest, before the US ends up planting stars and stripes over all the stars in heaven. Their article is a call to revolt, before it’s too late – or, as Byers puts it, “an awareness-raising exercise: other countries need to speak up”.

Weirdly enough, US law is already asserting its jurisdiction over space. In 2015, the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act said that it was OK for US citizens to own and sell portions of other celestial bodies – according to US law. No matter what Martians or Venusians or, for that matter, other Earthlings might have to say on the subject. It’s not exactly a worldview, unless you happen to confuse the United States with the world.

Luxembourg followed suit. And, so far as I know, they don’t even own a rocket. It’s part of what Byers and Boley say, paradoxically enough, is a “race to the bottom”, blowing a spaceship-sized gaping hole through any notion of all-inclusive rules and regulations. Soon we’re all going to be jumping on the warp-speed bandwagon, asserting our rights in law well in advance of any objective reality. It will surprise no one that Trump’s executive order explicitly dismisses the 1979 United Nations Moon Agreement as irrelevant and rejects the idea of a “global commons” according to which space is declared the “common heritage of mankind”.

Article II of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty says that “outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means”. Nasa says that it is operating in accordance with the Outer Space Treaty. But any notion of multilateral, collaborative approach to space mining is just unilaterally incinerated on the launchpad. America first, on this or any other planet. One small step for a man, one giant leap for homo Americanus. Nasa and the Elon Musk SpaceX private initiative (soon to be joined by the Jeff Bezos Blue Origin) look like the spearhead for a new Galactic Empire.

Russia, in particular, has denounced the Artemis Accords as a US conspiracy to pervert space law. Nasa administrator Jim Bridenstine draws an analogy between space and fishing on the high seas, beyond any national jurisdiction. A fish cannot be owned so long as it remains safely in the sea: but if someone should happen to hook the fish, then the fisherman owns the fish. Space mining is simply angling on an interplanetary scale. And as Byers and Boley note, “fishing without science-based regulation often leads to overexploitation and even destruction of stocks”.

Part of the problem is not just legal or theoretical but, in effect, ecological. We are talking about pollution and health and safety in this and other worlds. Mining has never been the most safety-conscious and risk-averse of pursuits. The list of great mining disasters would be as long as this article. And the names of the dead sacrificed in the cause of extracting lumps of coal and other valuable mineral deposits would stretch from here to the moon and back.

Now consider what it will be like in space. Safer? I don’t think so. Moons but especially asteroids have low or almost zero gravity. Anything that gets blasted out of the ground is going to keep on going. Space is going to be littered with debris. Stuff is going to be shooting back towards Earth. What goes up will eventually come down. And we – the people left in sublunary space – will be right in the firing line. I suspect that if an asteroid does eventually hit the Earth, as in our most apocalyptic nightmares, it will be because we aimed it in this direction and lost control, thereby becoming what Byers and Boley call “anthropogenic meteoroids”. What court could possibly prosecute the mad mining magnates of Jupiter? None at all, if the US has its way. The solar system is going to be like the Wild West, or possibly Alaska in the days of the Gold Rush, even if the new Regolith Rush will mostly be carried on by remote control. The same spirit of reckless and potentially lethal aggression will prevail. With the strong likelihood of ecocide. Not to mention the fact that we will actually be digging black holes in space.

SpaceX already has a Tesla electric car zooming through space roughly in the direction of Mars. Israel has smashed a robotic lander into the moon, bearing thousands of semi-indestructible “tardigrades”, micro-animals, now presumably swarming all over the Sea of Tranquillity. Ultimately, there will be lawyers in space, arguing over who owns what. But meanwhile we already have space lawyers, right here on Earth. Christopher Newman is a professor of space law and policy at the University of Northumbria in Newcastle and has already published widely on the subject. I fully expect Boris Johnson to announce that we are “world-beating” in the realm of space law.

Newman points out that there is ambiguity built into space law. “It’s true that Article II of the Outer Space Treaty prohibits national appropriation. But Article I says that states are free to use space and explore and investigate without restriction.” In other words, all celestial bodies should, in principle, remain “res communis omnium”, or “the province of all mankind”; but in practice that word “use” is a very broad church.

You might say that if you are mining a planet you are automatically appropriating it. But commercial entities will argue they are only looking to exploit the extraterrestrial environment and extract minerals and other natural resources. They are not making any grand claims, any more than say tin miners in Cornwall were saying they owned Cornwall. Newman says that, by the same token, even when the Americans landed the first men on the moon and planted the flag, “they stressed that they were not making territorial claims: they were only saying, we’re Americans and we’re happy to be here”.

Newman is more sympathetic to the Artemis Accords than Byers and Boley. “A lot of what it’s saying makes sense. To do with sharing data and taking care of debris and creating a zone of safety. A lot of existing space law is there. And anything that brings clarity to space is to be lauded.”

The Moon Treaty of 1979 makes it clear that “any mining that occurred on the moon and other celestial bodies should be administered by an international regime”. But, as Newman points out, the reality is that none of the major players in space – the US, Russia, China, Japan – have actually signed up to the treaty. “Indeed, America has explicitly repudiated it – and hopes that the Artemis Accords will become the established way of doing business on the moon.”

The US is heavily reliant on the tagline of the original Alien movie: In space, no one can hear you scream. Or protest about infringements of the law or getting clobbered by flying space junk. The post-truth is out there. The Astronomer Royal, Lord Martin Rees, reckons that we need to get “internationally agreed” rules for mining in space nailed down now because “it will be far harder when commercial pressures have really built up.”

In their article for Science, Byers and Boley urge the US to join in talks with the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, the body that drafted the original Outer Space treaties. But unless there is a change of president and a 180-degree rotation towards a more multinational – genuinely terrestrial – approach to the universe, you might as well wish for the moon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments