What can we learn from a 45-year-old handshake in space?

As we’re on the verge of another space race, Mick O’Hare looks back at the historic greeting between an American astronaut and Russian cosmonaut in 1975, which ushered in an era of space cooperation

The United States wants to play space rangers. That was the predictable charge emanating from Russia after Nasa announced in May that it has drawn up a set of principles for when it returns to the moon in 2024 (fingers crossed). Its partners, both national space agencies and private companies, would be expected to abide by what it is calling the Artemis Accords, named after its moonshot successor to Apollo. In other words, it wants everybody to behave nicely as the new moon rush kicks off and the accords, Nasa claims, are only there to make sure nobody steals the playground space hopper.

Common objectives, including peaceful rules of exploration, transparency of mission plans, exploitation of lunar resources, emergency aid, standardisation of design principles and a host of legal jargon comprise what the agency calls “Principles for a safe, peaceful and prosperous future”. Nasa insists the accords are in keeping with the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 – currently, the default document detailing law beyond our atmosphere – to which it is a ratified signatory, along with 108 other nations.

However, the United States’ rivals in space see the accords in a different light. China, ploughing its own furrow in orbit, seems set to ignore them while Russia has openly criticised the proposals as a means, no less, for the US to annex the moon. Dmitry Rogozin, head of the Russian space agency Roscosmos, described them as nothing more than a US plan to invade the lunar surface like it had “Iraq and Afghanistan”, and as a means of freezing Russia out of future collaborations. Nasa, for its part, claims it just wants to clarify what is acceptable in outer space and for the rules to apply to everybody.

Whatever the truth, it will surprise few that the US and Russia are mid-spat, considering their historical rivalry beyond the exosphere. From Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, to Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, to Apollo and the first moon landings, the struggle for supremacy between the United States and what was then the Soviet Union has been enduring. Recent earthbound political developments haven’t helped as an expanding Nato has pushed right up against Russia’s European border leading to tensions many had hoped dissipated by the fall of Eastern bloc communism.

So it may come as a surprise to learn that this July sees the 45th anniversary of an astonishing (with hindsight) joint mission in space between the US and the Soviet Union, slap bang in the middle of the Cold War. Back on Earth, the two nations were still pointing nuclear missiles at each other across the rigid ideological divide of the Iron Curtain, but 230 kilometres above the planet on 17 July 1975 it was all smiles, gifts and bonhomie as what was formally called the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) would become known as “the handshake in space”. Amid the dogmatic rhetoric of the Cold War this almost forgotten mission managed to unite – however briefly – the two space programmes and open up a window in a wall of otherwise intransigent mistrust.

So how? Only a few years earlier the two foes had faced each other down amid the Cuban missile crisis, and the war in Vietnam was barely concluded. Why were adversaries who had fought proxy wars all over the planet, now engaged in peaceful exploration?

To a certain extent, it was expediency. “Both nations had lost astronauts and cosmonauts,” says Cathleen Lewis, historian of international space programmes at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, and the curator of its Apollo-Soyuz exhibit. “The US had lost astronauts in the Apollo 1 fire in 1967 and the death of cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov that same year focused minds. But the demise of the crew of Soyuz 11 returning from the Salyut 1 space station in 1971 finally prompted consensus that both sides required joint rescue capability.”

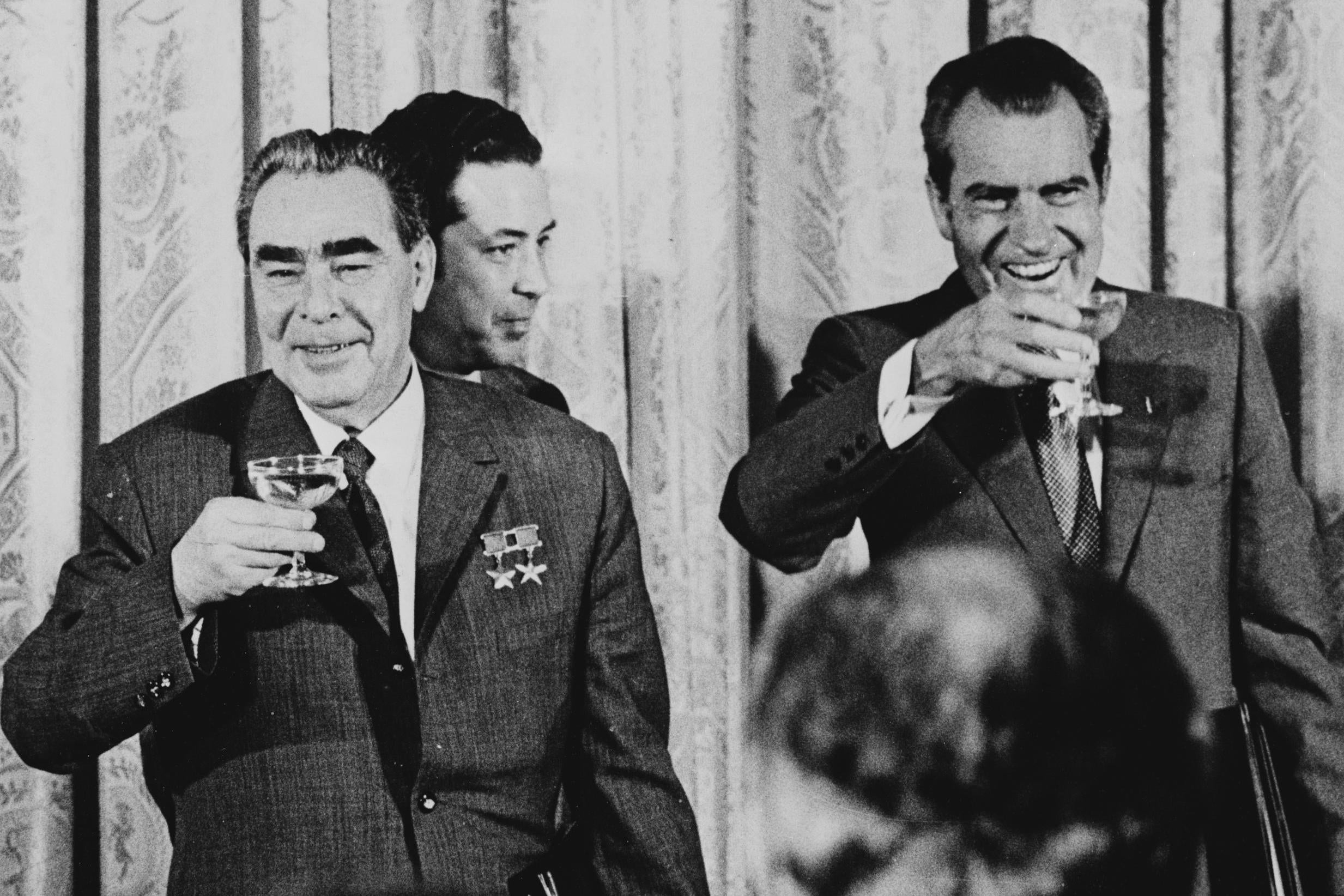

And the mission had a political dimension too. US president Richard Nixon, despite his subsequently exposed flaws, was scoping out ideas to build detente between the two nations. He and secretary of state Henry Kissinger picked up on an idea first proposed at the United Nations: a joint space mission between the two superpowers. Of course Nixon, typically the political pragmatist, had ulterior motives. “He wanted to engage the USSR and distract them from activities in Europe, the middle east and southeast Asia,” says Lewis. “The purpose of detente was to maintain contact that would be very public and unlikely to succumb to political and military conflict.” Space was an ideal territory.

Both administrations were entirely mistrustful, with staunch Cold War warriors on each side. Even the civilian engineers grew up in a climate of mistrust

The Soviets had their machinations too. They were about to cancel their long-held yet still clandestine plan to send cosmonauts to the moon, but premier Leonid Brezhnev wanted to maintain their human spaceflight programme, realising it carried kudos in the west and soft power to potential allies. “Participating in a project that would maintain the image of the USSR being equal to the US in space was an opportunity too good to miss,” says Lewis. Both nations were acutely aware peaceful acts played better with the wider world than conflict. In 1972 ASTP was signed off to go.

Two crews were selected: the Soviets under the command of Alexei Leonov, a Hero of the Soviet Union and the first man to walk in space in 1965, and the Americans under Thomas Stafford, the commander of Apollo 10 – the dry run for the Apollo 11 moon landing. Both sides were keen to present a positive face to the world meaning candidates were “their most diplomatically experienced and competent”, according to Lewis. Stafford had represented the US at the Soyuz 11 funeral and had developed personal relationships. He also had space-rendezvous experience. Things were similar on the Soviet side. Leonov had charisma and had become the Russian public’s favourite cosmonaut following the death of the revered Gagarin in 1968. Not only was Leonov the first person to spacewalk, but he would have also been the first man on the moon had the Soviet lunar programme succeeded.

There were still many obstacles, some obvious – the Vietnam War was still raging when the project got underway – others less so – there were technical and practical issues such as which atmosphere to use – Apollo used oxygen, Soyuz used air. And both nations used different systems for operations such as docking. Chris Kraft, former Nasa flight director, wrote that “the philosophies of design, development and operations were so widely separated that a chasm of differences had to be bridged”.

“Both administrations were entirely mistrustful,” explains Lewis, “with staunch Cold War warriors on each side. Even the civilian engineers grew up in a climate of mistrust. But eventually they found they spoke the same professional language.”

To solve the technical issues, engineers settled on what was termed “the androgynous docking adaptor”, essentially an airlock that allowed transfer between the two capsule atmospheres. But even this fell foul of the technocrats. “It should have been built jointly,” says Lewis, “but it proved impossible for both to work on it simultaneously – geography and pre-internet communications made it overly time-consuming.” In the end it was built in the US.

That camaraderie is best exemplified by the friendship between Stafford and recently deceased Leonov, to the extent that the latter become godfather to Stafford’s two adopted Russian sons

However, it proved something of an early metaphor for the notion of cooperation in space, being both a threat to the collaborative nature of the mission but crucially a challenge overcome. What may seem trivial now was very significant in that era of political one-upmanship. “It showed the sides could compromise,” says Lewis. “Ultimately it was produced by US company Rockwell but with close consultation with Soviet engineers.”

Of course, the crews mainly trained in their home environments but there were exchanges and visits throughout the years of preparation. “One key requirement was to learn each other’s language,” says Lewis. While this was part of the spirit of detente (or razryadka in Russian) it was also necessary should anything go disastrously wrong in space that required rapid action. Nobody wanted to be handing out the phrasebooks when a meteorite punctured one of the capsules. But sending Russian-speaking American government employees to the inner sanctums of the Soviet space programme and the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan was a godsend to the US security services (and vice versa, of course). “Certainly the spy agencies interviewed both crews on their return from visits,” says Lewis.

Naturally, some Cold War hawks were not happy about the mission at all, still all too aware that in the previous decade US President John F. Kennedy had declared the space race part of the “battle…. between freedom and tyranny”. SeNator William Proxmire of Wisconsin, demanded a postponement, if not a cancellation. He was unsuccessful, but some commentators thought it distasteful that the US should be collaborating (however briefly) with a nation they considered ideologically oppressive. Others denounced it as an American technological giveaway, but as Kraft said: “No one can build an Apollo or a Soyuz by reading a book or visiting a factory. The benefits accrued by working together probably outweigh any potential threat.”

On the Russian side, Brezhnev had sought out Leonov before giving the mission final approval. He asked his stalwart cosmonaut if he trusted the Americans. Leonov told him he did. And not only that, he believed that “coordinating efforts in space” was the future. “I knew their astronauts had different ideologies,” Leonov later said, “brought up, like us, to think their political systems (and indeed their spacecraft) were better. At times we even had harsh words. But there was more to unite us than divide us.” Leonov was notably utopian but, at the human level, his enthusiasm was shared.

Perhaps only a couple of hundred technicians, engineers, astronauts and managers ever came into direct contact with the other side, but despite initial wariness, many struck up enduring friendships, especially the flight crews. “Both nations have a reputation of welcoming strangers into their homes,” says Lewis. “There are plenty of anecdotal stories of barbecues and dacha visits,” and the cosmonauts made a very public visit to Disneyland during a trip to Florida. That camaraderie is best exemplified by the friendship between Stafford and recently deceased Leonov, to the extent that the latter become godfather to Stafford’s two adopted Russian sons.

Both spacecraft launched on 15 July – the last time Apollo ever flew although Soyuz is, in modified form, still in use today. Indeed, until May when a SpaceX Falcon 9 spacecraft took Americans to the International Space Station, Nasa had been relying on Russian-launched Soyuz craft to ferry its astronauts. Two days after launch Apollo and Soyuz docked. “Tovarich!” said Stafford, meaning “friend”, as he grasped Leonov’s hand. The eponymous handshake, broadcast worldwide, apparently took place over the French city of Metz. “The whole world is watching with rapt attention and admiration,” announced Brezhnev.

Throughout their 31 orbits, the crews exchanged flags and gifts, visited each other’s capsules, ate together and conversed in both languages (with Stafford’s Russian accent voted the worst). They also conducted experiments: exchanging native tree seeds later grown back on Earth and positioning Apollo to create a faux solar eclipse, allowing the sun’s corona to be studied from Soyuz. What could go wrong? Well, apart from noxious gas entering the Apollo capsule on splashdown and the craft flipping over in the ocean – both quickly rectified – very little it seems, save for the fact that, rather sadly, it was the only mission of its kind.

“That was a huge shame,” laments Lewis. “In the US it suffered from the dwindling public interest that plagued later Apollo missions. By launch date, the US had just finished its involvement in Vietnam and it was in the year following Nixon’s resignation, alongside a slew of other social and economic problems the country faced.” It was the last time Americans would fly in space until the Space Shuttle launched in 1981.

“On the other hand, people in the USSR were excited. It demonstrated they were capable of going one-on-one with the US, and the mission and joint ventures that ran alongside the programme were celebrated,” says Lewis. The room housing mission control in Korolyov near Moscow, where the Russians worked alongside the Americans, is now a shrine to the mission and Soyuz-Apollo brand cigarettes remain popular.

So, with detente frequently fraying today and political and military flashpoints still exercising earthbound governments, is there anything Apollo-Soyuz can teach us about international relations? Can our Covid-enveloped planet and its divided nations learn anything about mutual support and collaborative effort? Did the fellowship that, ostensibly at least, Nixon, Kissinger and Brezhnev strove for have lasting effect?

It seems crazy but at first we thought they were pretty aggressive people... and they probably thought we were monsters. So we quickly broke through that. You discover they’re human beings

Lewis believes that while the now largely uncelebrated mission was a success on many levels, its political aims slipped through the cracks somewhat. “Its long-term ramification was to demonstrate the US and USSR could work together in space. But there was no follow-through. However, the astronauts, cosmonauts, technicians and engineers were not to blame,” says Lewis. Instead, she points the finger at the Jackson-Vanik Amendment to the US Trade Act of 1974 which enforced strict limitations on cooperative programmes between the US and non-market economies. “That effectively put an end to follow-on ASTP projects,” she says, “and the future joint ventures developed as part of detente.”

On the other hand, she says the engineering feat showed that “people from different ideologies could work side by side. It led, perhaps, to more openness and, for example, it was the first time the Soviets announced which cosmonauts would be on board before launch while reporters were allowed to openly ask them questions.” It was also the first Soyuz launch televised live.

Of course, Nixon and Brezhnev, despite their mutual suspicion were very different from the strutting, bellicose Donald Trump and guileful Vladimir Putin, whose posturing nationalism is worn as a badge of bombastic honour. One can hardly imagine either echoing with any sincerity the words of Brezhnev: “The spacemen know our planet looks more beautiful from space. It is big enough for us to live peacefully on it.” Apollo-Soyuz was recognised by both sides as primarily an act of peace. Although both nations remained wedded to their philosophies – their media outlets reflecting the mission in terms of capitalist capability or Marxist ideology – equally it was seen wholly in a positive light. So while a new Apollo-Soyuz mission with or without Chinese involvement might be welcome today, is it even likely, as Leonov once hoped?

Lewis is equivocal. “Yes and no,” she says. “In many ways the ISS – where Russians and Americans among others work together today – is proof it can happen to some extent. But on the negative neither side – even excluding China – has the required delicate sense of diplomacy. Both administrations are far more unstable. Fortunately, while politicians can say whatever fool thing they want, they can’t pull the ISS down from the sky.”

And while in 1975 the brief thaw in the Cold War that was Apollo-Soyuz was soon subsumed by political machinations once again, Stafford’s colleague on the mission, Command Module pilot Vance Brand, remained aware of the benefits of collaboration in space, saying of his erstwhile Soviet companions: “It seems crazy but at first we thought they were pretty aggressive people… and they probably thought we were monsters. So we quickly broke through that. You discover they’re human beings. We were the foot in the door that started better communications.” For his part, Leonov was dismayed that soon after “all talk of razryadka disappeared from the political vocabulary once again”.

And what of the Artemis Accords? Does Lewis see them helping or hindering future partnerships? She believes the plans do not violate the Outer Space Treaty. “And with so many entities – governmental and private – planning missions, astronaut safety needs to be more assured than when only the US and the USSR were operating in space.” She suspects what irks the Russians most is the fear they will be excluded from the Artemis project. “However, Nasa has assured ISS partners – of which Russia is one – that they will have a role. There have been several bills before congress sanctioning Russia for its involvement in places such as Ukraine and Syria but they are not of the scope of Jackson-Vanik, but there is also a marked absence of anyone advocating joint activities to distract them in the way Apollo-Soyuz did,” she notes. Only time will tell whether Russia becomes a signatory to the accords.

Today, the two capsules involved in that historic link-up are to be found in the Californian Space Centre in Los Angeles and the Energiya Museum near Moscow, but a mockup of the docked spacecraft still hangs in Washington DC’s Air and Space Museum. Catch it while you can – Covid-19 permitting – because the collection is being revamped and it’s not certain when or where it will go back on display. The respect between the two groups of former Cold War enemies for the aims and ambitions of the mission extends to what they consider diplomatic territory too. Nobody from the museum has been inside the loaned Soyuz craft despite it hanging in Washington since 1976. “It’s like breaking into somebody’s sarcophagus, or climbing on their artwork. We wouldn’t do it,” says Lewis.

It is no hyperbole to say Apollo-Soyuz and its handshake gave the world hope at a difficult point in international relations. And the mission was a de facto coda to the space race. Ironically, without the Cold War it’s unlikely we would have had Sputnik, Vostok or Apollo, as the two rivals constantly tried to outmanoeuvre each other on Earth and around it – certainly there would not have been the hasty imperative that led to the golden era of the space race in the 1960s. But if competition, to twist a phrase, is the mother of invention, there must surely – in a blame-game world riven by Covid-19, short-term political opportunism, increasing distrust and intolerance – be room for collaboration. Tom Stafford gave the eulogy at Alexei Leonov’s funeral last year. They were both once members of opposing airforces, effectively trained to kill each other – but thanks to Apollo-Soyuz they parted as friends.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments