Will a new prime minister destabilise Keir Starmer’s leadership of Labour?

Depending on who wins the Tory leadership contest, Starmer will have to redefine his position, writes John Rentoul. But is he even the right person for the job?

We have lost Keir Starmer, said one of the presenters of the Today programme, when the Labour leader’s line was cut off in the middle of an interview last week. A few seconds later, the connection was partially restored, and the listeners could hear Starmer still talking, unaware that he’d been cut off, and unable to hear the presenters. He was faded out and the metaphor was complete.

Starmer is still talking, but the voters can hear him only intermittently, and he can’t hear them. The Conservative leadership contest is taking up most of the media’s bandwidth.

Starmer’s leadership has seemed surprisingly insecure for months. He started the instability in May by saying he would resign if he were fined by the Durham police for breaking coronavirus law. That prompted a flurry of speculation about Lisa Nandy and Wes Streeting – not so much about Angela Rayner because she had made the same promise to quit and attended the same campaign event.

But when, on 8 July, Starmer and Rayner were told that the police would not be issuing them with penalty notices, Starmer’s position wasn’t strengthened – because Boris Johnson had announced his resignation the day before. On the contrary, the change in leadership in government only prompted new questions about whether Starmer was still the best person to lead Labour into a general election against a different opponent. The moment of Starmer’s triumph over Johnson seemed more of a threat than an opportunity to the Labour leader.

Starmer had Johnson’s number. The leader of the opposition’s integrity, relative competence and plainness were assets against a prime minister who had abruptly and it seemed irrecoverably lost the confidence of the British people on precisely those attributes.

But now Starmer faces a new opponent who offers some of the same qualities he was selling. Liz Truss was untouched by the police inquiries into lockdown parties, and Rishi Sunak’s complicity in them is viewed very differently from the prime minister’s. Sunak was entitled to be surprised that he was fined for turning up early for a ministerial meeting, whereas most people are surprised that Johnson avoided being fined for any of the other gatherings.

Sunak, in particular, but also Truss, offer more focus and hard work as prime minister, and neither is likely to devote their speeches to running jokes, wordplay or light comic speculations on Peppa Pig World.

At a stroke, much of Starmer’s differentiation from the prime minister will disappear, drawing attention to Labour’s lack of policy detail and indeed the thinness of any substantive distinction between government and opposition. The only big policy difference was Labour’s plan for a windfall tax on the oil and gas companies, but Johnson and Sunak stole that as one of their last acts in government together.

On most occasions when a new prime minister has taken over between elections, the governing party has benefited. Anthony Eden resigned in disgrace in 1957 after Suez, and Harold Macmillan went on to increase the Conservative majority at the 1959 election; Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the opposition since 1955, couldn’t match Supermac’s broad appeal.

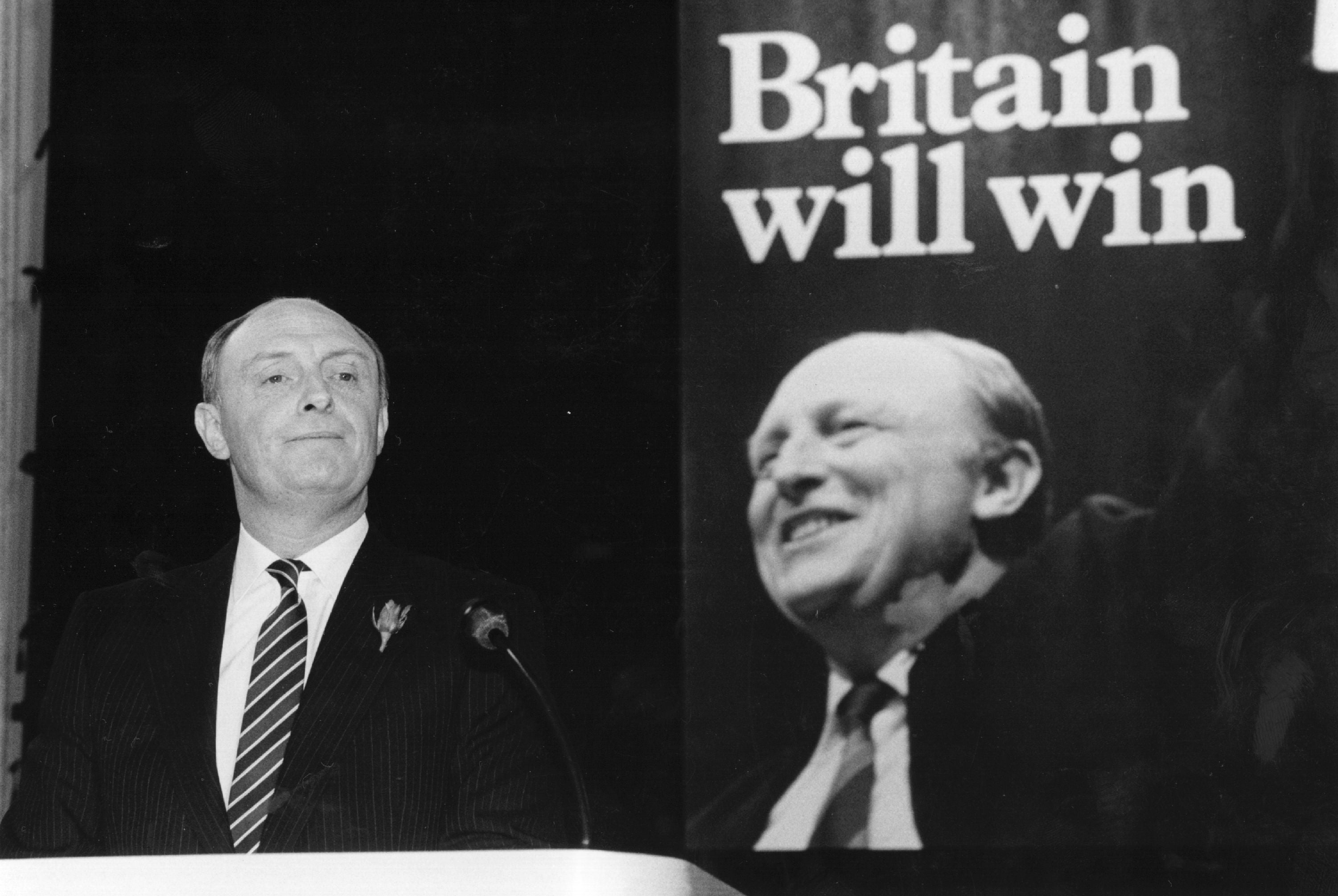

The public never took Kinnock to their hearts, but he neutralised his negatives and Thatcher became so unpopular that the voters seemed willing to put him in No 10 in the election that was expected

When Macmillan was mired in scandal a few years later, he gave way to Alec Douglas-Home, who did a remarkable job of nearly rescuing the Tories, but Harold Wilson, who became Labour leader eight months before the changeover in No 10, readily adjusted from attacking one patrician Tory to attacking another and won the 1964 election by a narrow margin. When he gave way in turn to James Callaghan in 1976, he gave his successor a chance of winning – if there had been an election in 1978. Margaret Thatcher, newly elected leader of the opposition in 1975, didn’t need to adjust her stance as one experienced Labour politician succeeded another, and prevailed in 1979 after Callaghan waited too long, allowing the trade unions to destroy his government.

The closer parallel to today was the next change of prime minister. Neil Kinnock finally felt that he had the measure of Thatcher in 1989. A Labour policy review – “Meet the Challenge, Make the Change” – had disposed of the most obvious vote-losing policies from the party’s programme, above all that of one-sided nuclear disarmament. The professionalisation of the party’s image-making continued to improve, and Labour enjoyed a consistent small lead in the opinion polls, which widened into a 12-point lead after the poll tax riots in 1990.

The public never took Kinnock to their hearts, but he neutralised his negatives and Thatcher became so unpopular that the voters seemed willing to put him in No 10 in the election that was expected to be called in 1991. But then she was gone. Labour’s very success in presenting itself as an electable alternative spooked Conservative MPs into getting rid of a world-historical leader because she stubbornly refused to abandon the poll tax.

She was replaced by a mild, one-nation Conservative whose origins were humbler than hers and about as working class as Kinnock’s. Labour’s poll lead vanished overnight. Kinnock, who had worked so hard at presenting himself as the down-to-earth, moderate alternative to Thatcher’s out-of-touch extremism, found himself opposing a down-to-earth, moderate prime minister. He found it hard to adjust, not knowing whether to attack John Major for being a Thatcherite wolf in sheep’s clothing, or for being an opportunist who didn’t believe in anything.

Inertia meant that Labour inevitably tended to the first approach, accusing Major of being an inauthentic salesperson for a right-wing government defending the interests of the rich. That meant Major and Norman Lamont could outflank Kinnock by unveiling a pre-election Budget that did more for those on middle and lower incomes than Labour was promising. A ruthless election campaign focused on the folk-memory of Labour’s record of economic mismanagement finished the job.

Starmer is about to find himself facing a similar dilemma. Assuming Truss is prime minister next month, should he attack her for cutting taxes and increasing borrowing? Or should he disagree with the form of the tax cuts, while accepting a significant loosening of the fiscal position?

So far, Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, seems to be leaning to the first position, lining up behind Sunak’s criticism of Truss’s unfunded tax cuts. Early in the leadership campaign, she said: “The level of unfunded tax cuts currently being bandied about by [the candidates] would blow a massive hole in the public finances”. She went on: “We are presented with the extraordinary spectacle of a Tory tombola of tax cuts – with no explanation of what public services will be cut, or how else they’d be paid for.”

That is going to be a difficult position to maintain, especially as the tax cuts, when they are announced in her chancellor’s emergency Budget in September, are likely to be popular. It won’t be possible for Starmer and Reeves to wait for things to go wrong – for inflation and mortgage rates to lurch upwards – so that they can then say: “Sunak was right.” They would have to take a position on the tax cuts, and the overall borrowing requirement, on the day of the Budget. They should not try to fudge it, because keeping his options open is already becoming one of Starmer’s defining weaknesses.

My guess is that Truss’s tax cuts would not be as dramatic as advertised in advance. What is more, she and her chancellor may well decide that cutting income tax would yield a greater political dividend than reversing the less visible rise in employers’ national insurance contributions, or cancelling next year’s planned rise in corporation tax, as she has promised to do.

If Truss does cancel the corporation tax rise, or raise the rate by less than the six percentage points planned by Sunak, that could become a dividing line between the parties. Labour might be comfortable proposing a small increase in corporation tax to pay for its signature policies – whatever they will be – because the voters may be happy to let big business pay the bills. After all, even New Labour had a windfall tax on the privatised utilities to pay for its modest promises on the pledge card in 1997.

That is why Sunak might ultimately be a trickier opponent for Starmer because his corporation tax rise would close off that avenue to differentiation for Labour. Although Sunak is competing with Truss to be seen as a tax-cutting punk Thatcherite now, if he were prime minister we would expect to see more of his instinct for going after Labour voters that was evident in furlough and the help with energy bills that is skewed towards those on lower incomes. A Sunak government could be rather like Major’s in 1992, moving in on Labour territory, led by someone Labour people feel less hostile towards, certainly compared to his predecessor.

Which brings up an awkward lesson from the past, which is whether Labour needs to change its leader to match the change on the government side. In 1992 the question was suppressed because the opinion polls overstated Labour support. As long as Kinnock looked as if he was going to win, or at least, to be prime minister in a hung parliament, the dissatisfaction with him in the shadow cabinet could find no ready expression. There was talk of replacing him with John Smith, the shadow chancellor, but it came to nothing. After the election was lost, Smith’s friends said that he should have been leader and that he would have beaten Major, but no one will ever know.

Here we are again. For the moment, the opinion polls put Labour ahead, but the gap is narrowing as the Conservatives dominate media attention. It is likely that the new prime minister will enjoy a bounce in the polls. There might even be speculation about an early election, such as the one Brown didn’t call in 2007 and Theresa May did 10 years later. By then it might seem too late for Labour to change its leader, although it is always worth remembering the example of Bob Hawke, who became leader of the Australian Labor Party after the election was called in 1983 and who went on to win it, and the next three.

More likely, though, would be a short honeymoon before the new prime minister is swallowed by the crises of inflation and economic dislocation, which might allow Starmer to pose as a competent and compassionate alternative. Or it might mean that the voters felt safer sticking with the Conservative – especially if it is Sunak – than taking a risk with Labour. If that sentiment were reflected in the opinion polls, the rumbling of discontent with Starmer in the party might grow.

The crystal ball goes cloudy at this point, although some stubborn facts can be made out in the murk. One is that it is hard to get rid of a Labour leader who doesn’t want to go. The rules require 40 MPs to support a challenger at the party’s annual conference. So if Nandy, Rayner and Streeting are positioning themselves for a future leadership contest, that is more likely to take place after the next general election than before. It is possible to imagine that there might be a leadership crisis before then, in which case the issue of supporting trade unions on strike could play into a period of industrial strife. Even so, it is hard to see a way in which Nandy or Rayner, with their pro-union poses, could use the issue to topple Starmer and then to present themselves as an alternative prime minister, better able to give the unions what they want, as Harold Wilson did in 1974.

Equally, it is hard to see Streeting or Reeves posing a threat to Starmer from the so-called right. Streeting is a better communicator, and Reeves might have more credibility as a manager of the economy, as Smith did in 1992, but would Labour MPs move against Starmer, in the way that Tory MPs moved against Boris Johnson, in the run-up to the general election?

It seems likely that, when Starmer’s line is reconnected after the interruption caused by the Tory leadership election, we will find that he is still talking, and that he will lead the Labour Party into the general election, for good or ill.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments