Beauvoir, Sartre and the seduction of young schoolgirls

Simone de Beauvoir was teaching philosophy in Paris in 1943 when she was sacked for ‘behaviour leading to the debauching of a minor’. Andy Martin writes about a new book that confirms her passion for adolescent girls

The year is 1943. We are in occupied Paris. The Second World War is in full swing, even if the tide is turning. But war or no war, education in France remains a priority and French children are still going to school and taking their baccalaureat and (unlike in the UK and US) studying philosophy. And Simone de Beauvoir is still teaching them philosophy. Until, that is, she is sacked, for the offence of “excitation de mineure à la debauche” – behaviour leading to the debauching of a minor. De Beauvoir the debaucher.

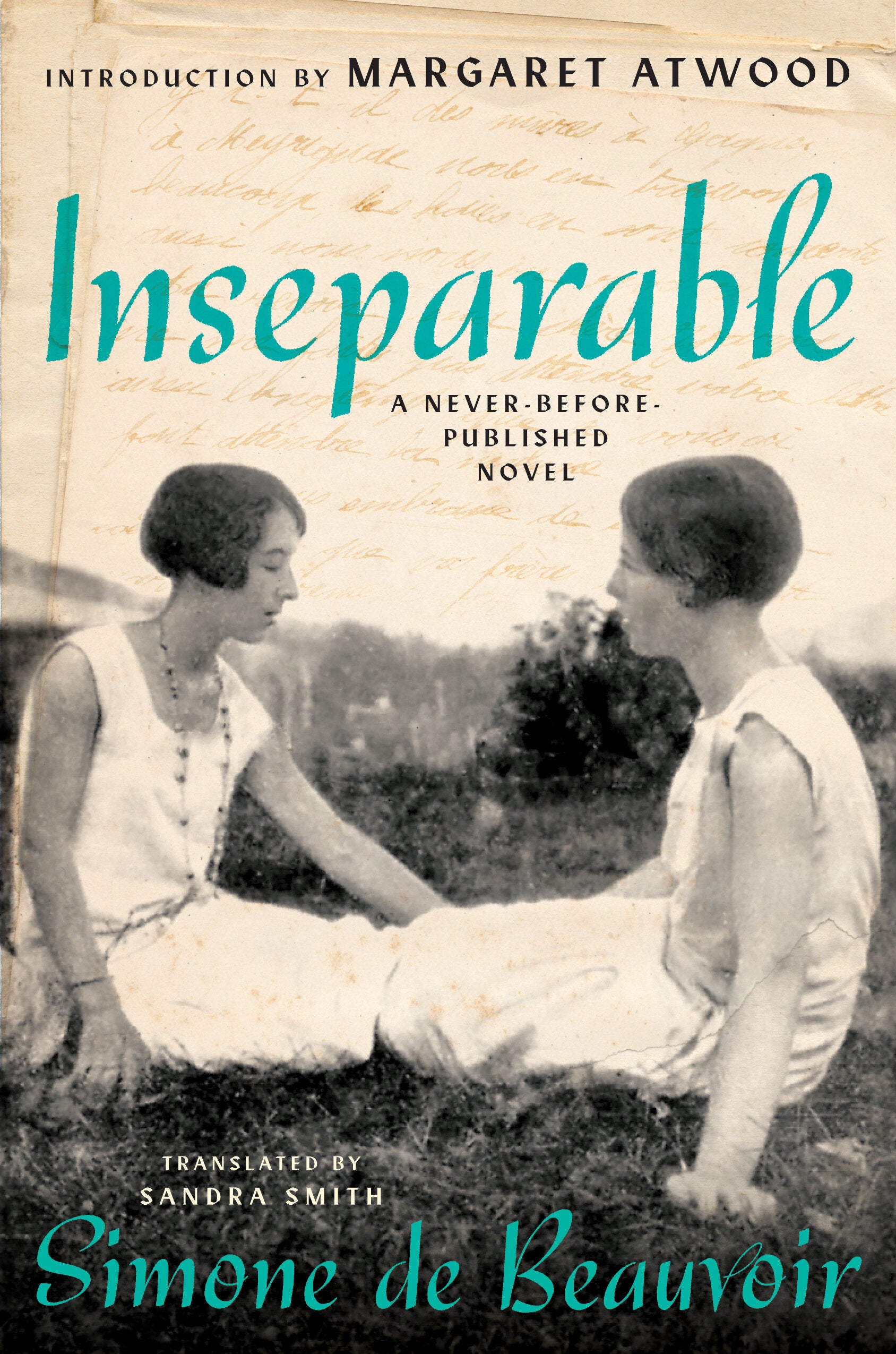

It is a curious little-known episode amid the dark history of the occupation, of collaboration and resistance, and almost forgettable, except that I found myself constantly reminded of it in reading Beauvoir’s new novel, Inseparable. Beauvoir, author of The Second Sex, philosopher, memoirist, novelist, feminist, existentialist, died in 1986. But this is a novel – “novella” would be more accurate, amounting to around 30,000 words and a hundred or so pages – she wrote in 1954 but left unpublished in her lifetime.

I have to admit: I haven’t read the original Les Inséparables. But I have to give a shout-out to the translator, Sandra Smith, who makes it appear that Simone de Beauvoir wrote elegant, lyrical, passionate and lucid English. (The other translation currently out there is idiotically and impossibly entitled “The Inseparables”.) Inseparable tells the story of the love that the young narrator, Sylvie Lepage, has for another schoolgirl, Andrée Gallard. In her afterword, Beauvoir’s adopted daughter, Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, reveals that the story is based on the adolescent crush that Beauvoir herself had on “Zaza”, Elisabeth Lecoin, whose death at the age of only 21 was a “catastrophe” for her. But the author’s dedication “to Zaza” gives most of it away: “If I have tears in my eyes tonight, is it because you have died, or rather because I’m the one who is still alive?”

In her introduction, Margaret Atwood argues that “Beauvoir’s freshest and most immediate work comes directly from her own experience”. She sees the novel as softening our image of Beauvoir. Atwood first encountered the writings of the French existentialist thinkers in her twenties in Canada. She read The Second Sex in Vancouver in 1954. “How frighteningly tough she [Beauvoir] must be, I thought, to be holding her own among the super-intellectual steely brained Parisian Olympians!”

She was “terrified” of Beauvoir, but at the same time eager to replicate this “grandmother of second-wave feminism”. “It was a time when women who aspired to be more than embodiments of assigned gender roles felt they had to comport themselves like macho men – coldly, with avowed self-interest –while seizing the initiative, even the sexual initiative. A bon mot here, a slapping away of a wandering hand there, an insouciant affair, or two, or 20, followed by cigarettes, as in films.”

In the era of Brigitte Bardot, women were reclaiming erotic freedom. But there is a darker side to the sexuality of Simone de Beauvoir that it is impossible to forget in reading this novel, captured in the title of the essay about Bardot that she declared was her personal favourite, “The Lolita Syndrome”. Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir says that Zaza’s death inspired Beauvoir: “To counteract the void and to never forget her, Simone’s only recourse is the alchemy of literature.” But this is an awkward, embarrassing and fundamentally misleading interpretation. It was never just theory for Beauvoir. She was always driven to act out her desires and put theory into practice. If you were repressed, you needed to be liberated. It was the history of the Second World War applied to the territory of relationships.

In the book, in the midst of the First World War, Sylvie has intense romantic feelings towards the quirky and subversive Andrée (Zaza), her classmate, and is frustrated by her object of desire’s inability to respond or reciprocate. Andrée is an irreverent violinist with a passion for literature and a tendency to self-harm (notably involving an axe) and half in love with easeful death. She is oppressed by her strict family, and the school and the church, but also repressed.

Sylvie, the Beauvoiresque narrator, is less willingly restrained. The relationship between them could be described as an “innocent” love affair, since it is unconsummated and all the more intense. “I loved Andrée more than anything, and she was here with me.” Sylvie is correspondingly distraught in Andrée’s absence. “I suddenly understood, with astonishment and joy, that the emptiness in my heart, my gloomy feeling of recent days, had only one cause: the absence of Andrée. Living without her was no longer living.”

Her psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, hypothesised that the two philosophers assumed the position of symbolic parents, so were committing quasi-incest

But Andrée doesn’t get it: “That was what saddened me the most: I had just realised that she had absolutely no idea of my feelings for her…. I would walk for two days and two nights without eating or drinking to see Andrée for an hour, to spare her any pain: and she had no idea!” Sylvie finally has to spell out to her exactly how she feels when they get drunk one day in a cellar. “You never knew this, but from the day I met you, you’ve meant everything to me. I’d decided that if you died, I would die immediately.”

There are subtle hints of carnal desire: “When she came to my house to see my notebooks, I looked at her with respect; she took notes in beautiful handwriting, and I thought about her swollen thigh under her pleated skirt.” And “when I thought back to that hour spent in the kitchen, I was sad to think that, in truth, nothing had happened”. Sylvie is already an atheist; Andrée is a believer and is ultimately drawn to the impossibly spiritual and strait-laced Pascal, who tells Sylvie that “the intimacy of being engaged is not easy for Christians. Andrée is a real woman, a woman of flesh and blood. Even if we didn’t give in to temptation, we would always be aware of it: that type of obsession is a sin in itself.”

Andrée, likewise, is apprehensive of any sexual initiation: “Shortly after my visit to Béthary – Andrée was only 15 then – Madame Gallard had told her about the birds and the bees with such intensity and minute detail that she still shuddered when thinking back on it.”

Ever since that night in the kitchen in Béthary when I’d admitted to Andrée how much she meant to me, I had decided to make myself care about her a little less

To some extent Sylvie/Simone seems to get over it. “Ever since that night in the kitchen in Béthary when I’d admitted to Andrée how much she meant to me, I had decided to make myself care about her a little less.” But does she? Atwood reckons not. Her relationship with Zaza is “the single most influential experience of Beauvoir’s life”.

Inseparable is a brilliant, heartfelt portrayal of young love between two girls growing up. But this isn’t a diary. It’s written by the mature, contemplative Beauvoir, a few years after The Second Sex and a few years before the first volume of her autobiography, Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée. In Inseparable, Beauvoir writes: “I was very well informed about sexual issues, for during my childhood and adolescence, my body had had its desires, but neither my considerable wisdom nor my infinitesimal experience could explain the ties that united the flesh to tenderness, or happiness.” But her underlying premise was that if you can theorise it, you can do it – you should do it.

As Atwood points out, Beauvoir “made the mistake of showing [Inseparable] to Sartre”. Jean-Paul Sartre, the high priest of existentialism, was her semi-lifelong partner and confidante and collaborator. The “Beaver” (as he called her) was his chief confidante. They liked to say (borrowing from Hegel) that their quasi-marital relationship was “necessary” while all the other countless love affairs they would have were “contingent”. Each would be the other’s “pivotal(e)” (taking this term from the 19th-century utopian thinker Charles Fourier). She always would show him her work since they shared everything. Including lovers. Which would include schoolgirls.

Sartre himself was no great believer in love. No wonder he dismissed Beauvoir’s novel as insignificant (“seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest”) and persuaded her to set it aside. Perhaps there is a hint in that judgement of coercive control. According to Sartre’s classic work, Being and Nothingness, love is nothing but the desire to be loved, and relationships boil down to two basic options, sadism and masochism. You are either dominating or being objectified. If you are not controlling, then you are being controlled. Sartre was controlling Beauvoir, and Beauvoir in turn was controlling her own students.

At some point in the 1930s, while Beauvoir was teaching philosophy at a Paris lycée and dazzling her students with her radical ideas, a ménage à trois style serial relationship emerged – which they called the “trio” – in which Beauvoir would seduce one of her students, first intellectually and then physically, and when she had tired of her, would pass her on to Sartre. In today’s terms, with the addition of a lot of philosophical sugar coating, it’s not a million miles away from Jeffrey Epstein and – according to the allegations made against her – Ghislaine Maxwell. Beauvoir acted as a procurer for the avowedly “ugly bastard” existentialist.

Beauvoir and Sartre, in their explicit way, don’t hesitate to mention what was going on but the best account of it is written from the point of view of one of the third constituents of the trio. Mémoires d’une jeune fille dérangée – published in 1993 and translated as A Disgraceful Affair – is a play on the title of Beauvoir’s memoir, replacing rangée (orderly or well-behaved) by dérangée (disturbed verging on deranged). Bianca Lamblin (née Bienenfeld) was infatuated with her predatory teacher but rather resented being lined up to provide services to the great Sartre. Her psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, hypothesised that the two philosophers assumed the position of symbolic parents, so were committing quasi-incest. In any case, the Sartrian one-liner, “Hell is other people” (from his play about three people – two women and one man – who realise they are in hell) has rarely been so well dramatised. And it reminds you of Sartre’s description of sex as “consensual rape”.

Morality was like that for Beauvoir too, a footnote – a future work or a bourgeois malaise, something to be transcended, so that à la Nietzsche you were finally beyond good and evil

In Lamblin’s account, Sartre finally persuades the highly ambivalent Bianca to go to the hotel he lives in to consummate the affair. He didn’t bother to tell her he loved her or anything like that. Instead, as they approached the hotel, he turned to her and said: “You know, the chambermaid is liable to be rather surprised. Only the other day she found me taking the virginity of some other young girl.” The trio routine had become a regular assembly line. One writer has spoken of the “sexual colonisation” of Beauvoir’s pupils. Sartre’s word for what he was doing was “de-virginisation”. If Sartre was using Beauvoir, she in turn sought to manipulate and subjugate people around her. Especially students. The bright, precocious ones like Zaza, but now powerless to resist her.

Inseparable manages to imply that Andrée/Zaza dies because she isn’t allowed to have sex (overbearing parents, suffocating boyfriend, mixed together with her own anxiety). Beauvoir escapes but she doesn’t. Perhaps, it is implied, if only she could have escaped that highly restrictive morality, she could have been saved. Sex might have saved her. And this seems to be the lesson that she taught her own students.

If you strip back all the subtleties of existentialism, what you are left with is a hardcore of extreme individualism, adventures in naked self-interest. The other’s only raison d’être is to confirm (or, more likely, destroy) your existence. Sartre disavowed his more narrowly egocentric formulations. He once wrote to Beauvoir: “I quite profoundly and sincerely feel myself to be a bastard. And a small-scale bastard at that, a sickening sort of academic sadist, a bureaucratic Don Juan.” I’m not sure that Beauvoir ever renounced her original position.

In The Prime of Life (1961) Beauvoir admits to her attraction to pubescent girls. Her essay, “Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome”, written around the same time, reveals Bardot as a lightly encoded avatar of Beauvoir herself, falsely accused of having “corrupted the youth of France”. Beauvoir offers an evangelical defence of the sexual emancipation of the young. She stresses sexual equality and autonomy, but she also insists on the “charms of the ‘nymph’ in whom the fearsome image of the wife and the mother is not yet visible”. In incendiary rhetoric that is half-French Revolution, half-Marxian, with a dash of Nabokov, she sees her role as breaking down sexual taboos. “Children ceaselessly ask: Why? Why not? Are we going to stifle the questions that BB has raised?”

Beauvoir and Sartre both hark back to the work of Charles Fourier, whose sexual social utopia of the “phalanstery” was based largely on Bougainville’s account of his discovery of Tahiti in which “young girls” are depicted as waylaying and seducing French sailors. The generation of soixante huitards – veterans of the Événements of 1968 – did their best to enact Fourier’s theories in a paradigm of theory and praxis that Jean Baudrillard once characterised as “the orgy”. Beauvoir wanted to be a revolutionary in everything – and to hell with a little spilt blood. She agreed with the old ’68 slogan,“Il est interdit d’interdire!” (“It is forbidden to forbid!”)

In the 1970s, in the age of the Paedophile Information Exchange in the UK, we find Beauvoir joining forces with Sartre and Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida to put their names to a petition aiming to decriminalise paedophilia. She thought that giving girls like Andrée/Zaza the right to choose was striking a blow for freedom. “French law… should acknowledge the right of children and adolescents to have relations with whomever they choose.” Beauvoir was not a paedophile but she was a hebephile (or ephebophile) – attracted to girls in the Lolita category and beyond – and therefore sympathised with those who sought out sex with children. She saw paedophiles as a maligned minority.

In a footnote to the conclusion of the 700-odd pages of Being and Nothingness, Sartre promises to turn his attention in a future work to the question of ethics. Morality was like that for Beauvoir too, a footnote – a future work or a bourgeois malaise, something to be transcended, so that à la Nietzsche you were finally beyond good and evil. It’s not that surprising that she was a great fan of the Marquis de Sade too (as per her essay, “Faut-il brûler Sade?”).

It is ironic that Margaret Atwood, whose The Handmaid’s Tale drills deep into the labyrinth of sexual coercion, appears blind to – or oblivious of – Beauvoir’s own history of manipulations and subjugations. The Second Sex did so much to assert and restore women’s rights to sexual freedom. But did that include girls’ rights to have sex? What about the right not to? Beauvoir had a great cause, but she had little sense of consequences.

Beauvoir’s Lolita syndrome suggests that liberation and “authenticity” are sometimes indistinguishable from coercion because they turn the very notion of “freedom” into a categorical imperative. In Inseparable, there is a distant echo of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s notion that some people need to be “forced to be free”.

‘Inseparable’ by Simone De Beauvoir is published by Harper Collins

Andy Martin is the author of ‘The Boxer and the Goalkeeper: Sartre versus Camus’ (Simon and Schuster)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments