Baudelaire will always be the first modern man

He was a rebel who believed in art for art’s sake, writes Kevin Childs. His life was scarred by alcoholism, penury and complicated love, but in the end Baudelaire changed what it meant to be a poet and a man

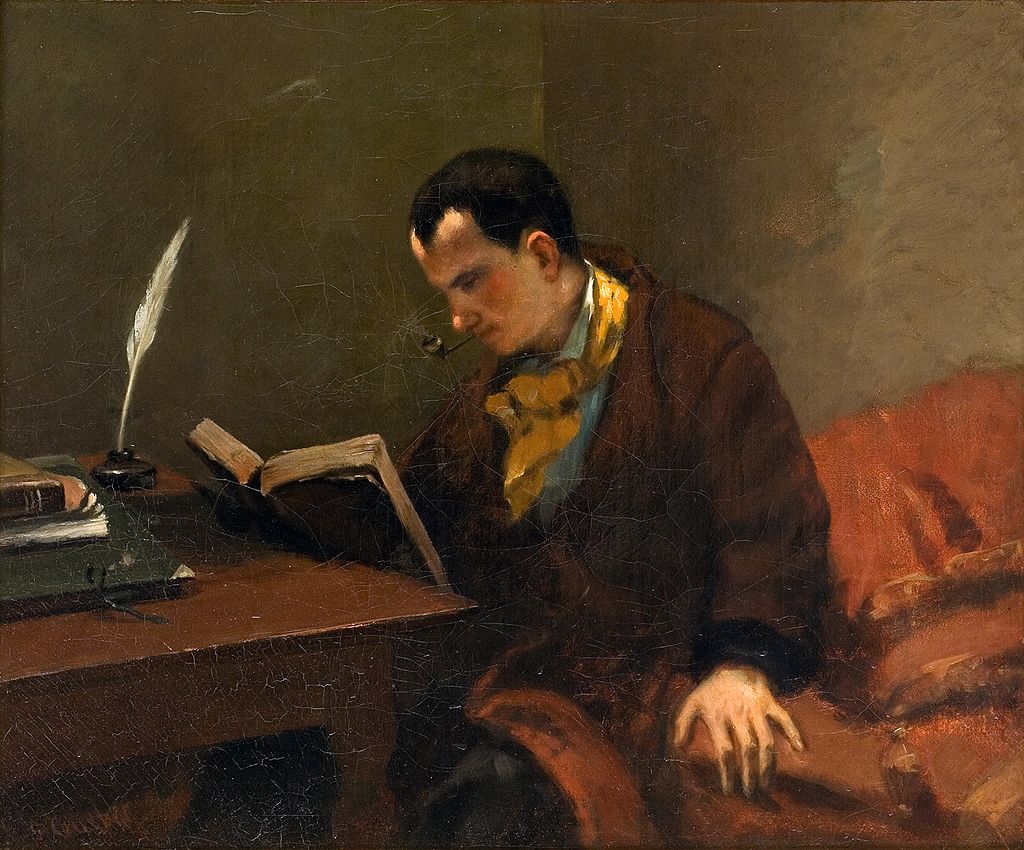

In a small garret room on the Isle Saint Louis in Paris, Charles Baudelaire sits and writes. He has a fuming pipe in his mouth, a book propped against his table, and there is a gleaming white goose quill jutting out from its ink pot. His face is pink and yellow and there’s a boozy flush on his cheeks, a gleam of light on the tip of his nose.

One pale, thin hand rests on the side of the sofa jammed up against the corner of the room to act as day bed and work station, everything is doubled up, economised, spare, except for the flash of an extravagant gold silk cravat about his neck that betrays the shoestring dandy. In Gustave Courbet’s portrait, Baudelaire’s teaming brain is reconstituting life as poetry, foraging in the gutter for jewels, but, above all, searching for a way to distil the beauty of the eternal present.

On this occasion he’d been reading a little too much of the sort of political sermonising to the poor that ushered in the revolution of 1848 and he needed a drink. Lacing up his good English boots, a little down at heel, but serviceable still, he heads for a tavern not far away, only to be accosted at the door by a beggar, a particularly decrepit example, he thinks, of the very people who were the object of all his reading. Instead of giving him a few centimes, Baudelaire sets about him with his fists and boots, provoking the much stronger beggar into giving him a real black-eyed drubbing. Now on the ground, with the other man towering over him, through bloodied and broken teeth, laughing, the poet calls a truce: “Monsieur, you are my equal! Do me the honour of sharing with me my purse. And remember, if you are truly philanthropic, to apply to your brothers, when they demand money from you, the theory that I’ve taken pains to drum into your bones.”

He staggered into the tavern and took a glass of wine, drinking it in gulps before his equilibrium was restored and he could sit and think again without trembling.

The poet

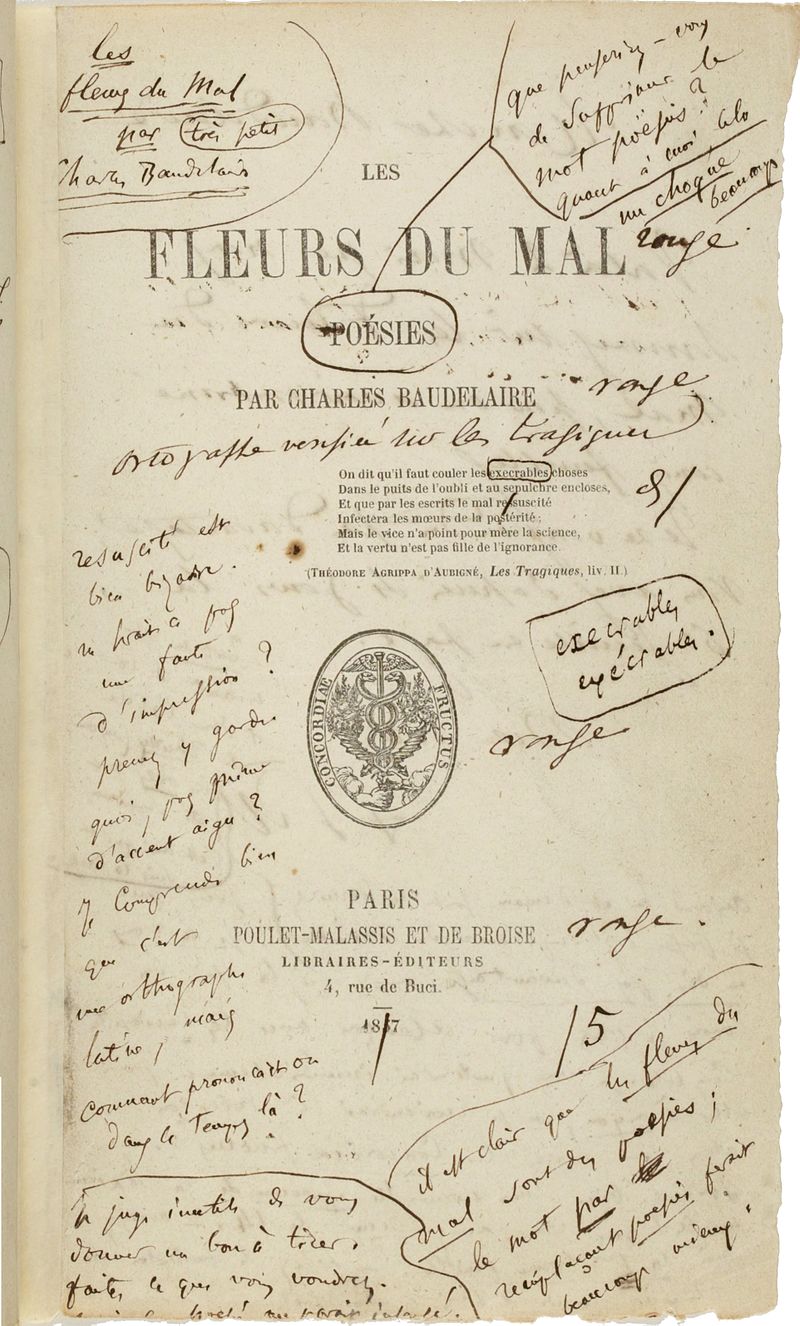

It is fiction. Just one of Baudelaire’s prose poems which would be published in a collection called Paris Spleen. It’s also shocking and intended to be, but at its heart is a story about dignity in a society, the fundamentally capitalist values of which tend to stifle humanity. Details ring true, however, particularly the uncompromising irony, and the need to drink. In fact, Baudelaire is perhaps one of the most famous drinkers in history – he would write about wine and make an invidious comparison with hashish and opium in his search for the perfect medium for or route to what he termed “Artificial Paradises” – but he was also one of the most brilliant versifiers in the French language and, because of his contempt for the 19th century, a great literary gadfly to bourgeois sensibilities. In the collection of poetry that is his most enduring legacy, Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), the social criminal, from his particular stained plush sofa, sated with drink and sex, self-loathing, invites the reader not so much to join him, but to recognise their own reflection:

Dreaming of gallows, while smoking his weed.

You know him, reader, his delicate breed

– Hypocrite reader – my double – my brother!

– ‘To the Reader’

It was maddening for his public to be confronted with their own sordidness. Gustave Bourdin, writing in Le Figaro, singled out a few poems, the ones which dealt with lesbian love and the blasphemous “The Denial of St Peter” – which concludes with the observation, “Saint Peter denied Jesus – he did well” – as warranting investigation by the Ministry of Justice. It was 1857. Something had to be done. Friends and literary fans melted away when asked to review the collection. A few positive notices were suppressed. And so, in time, the volume – one of the greatest collections of poetry in the history of the art – was impounded and put on trial, and Baudelaire and his publisher condemned and fined on grounds of moral probity for a handful of its contents. The offending poems were ordered to be removed from any subsequent editions. When asked if he had expected to have been acquitted, Baudelaire replied: “Acquitted! I expected a full apology!”

But when he died 10 years later from a combination of the effects of incipient syphilis, opium addiction and alcoholism, he was already being canonised by the young writers and artists – Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, Gustave Moreau, Édouard Manet – who would foment the culture of the fin de siècle with so much modernism. The painter Henri Fantin-Latour planned a picture celebrating Baudelaire, in the form of a portrait within a portrait, among a congregation of fellow writers paying homage.

Across the Channel, in an anglophone world the culture of which he’d come to love, his name would be invoked to condemn anything strange, perverse – frankly modern – from Swinburne’s verse to Pater’s prose, via Whistler’s “Nocturnes” and some of the Pre-Raphaelites more outré savageries. Oscar Wilde confessed his debt in Salome, The Decay of Lying, even The Picture of Dorian Gray. Baudelaire was a conundrum: a Catholic apostate, a believer in damnation, on which he blamed his own lack of success in this world, an immoral moralist, a believer in women’s rights to determine their own lives, an innovator, a translator, a revolutionary and a reactionary, a socialist flâneur whose attitude towards the evils of modern French society could be characterised in the prose poem with which I began, significantly too close to the bone to be published in his life time.

Why is this habitué of the demi-monde, whose qualities cannot be summed up without resorting to the sort of French clichés current in his own time, still relevant? Because he was and always will be the first modern man. For Baudelaire, modernity – a word he coined – was “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and immoveable”.

He was the first to celebrate the moment, being in the moment, capturing its special distillation. He saw modernity in cities and crowds, resonating in a tale written by Edgar Allen Poe and translated by him in which a man sat, convalescing from a long illness, watching the world go by in the rain from the window of a café. Back from the dead, so to speak, the convalescent breathes in “all the germs and all the scents of life” from the throng. But he’s detached from it, looking on, not yet able to join its ebb and flow. Such moments are “like a return to childhood; the child sees everything in a state of newness; he is always drunk”. Being both alive and vital to the rush of life and simultaneously anonymous is a state of poetic reverie, these fugitive moments in a busy crowd were the essence of life and art for him.

The modern man

Charles Baudelaire took his first breaths 200 years ago in Paris and a little before the Emperor Napoleon breathed his last on far-away Saint Helena. As with everyone on the continent of Europe, Napoleon would cast his strange influence over the poet’s life. His father died when he was six. A kind, elderly ex-priest and Imperial functionary, Joseph-François Baudelaire was passionate about art and the theatre. He would take his young son on walks through the Luxembourg Gardens, near to where they lived in Paris, hand-in-hand, while he talked about his favourite plays and pictures from the loot which the Emperor had gathered in the Louvre.

Baudelaire’s mother, Caroline, was 34 years younger than her husband. When he died, within a year she’d remarried a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, Jacques Aupick, who made a career out of switching sides, serving both the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy, before eventually becoming ambassador to Constantinople and then Madrid under Napoleon III.

Charles and Aupick didn’t see eye to eye. The poet always resented his stepfather’s place in his mother’s heart, as well as his stern belief in a career open to talent, as long as that career involved the army or the civil service. Colonel, later General Aupick had no time for his stepson’s literary ambitions. When Baudelaire inherited money from his father’s estate at the age of 21, Aupick lost little time in getting a court to declare him financially incompetent and in need of a sort of official fiscal guardian. Baudelaire would be in the humiliating position of remaining a minor for the rest of his life, dependent on his mother and his mother’s relationship with his stepfather, chronically short of funds and in debt, condemned to sordid living arrangements and rapacious landlords.

Under such circumstances, most would buckle, and Baudelaire does seem to have attempted suicide in 1845, when he was 24: “There are times,” he wrote, “when the desire comes over me to sleep without end, but I cannot sleep because I’m always thinking.” What’s remarkable is the amount of work he was able to produce over the next two decades, in prose, in verse, works of such daring novelty and troubling honesty:

In a sweeter-than-death forget,

I will scatter my kisses without regret

On your body’s shining copper stain.

To tranquilise my bottomless distress

There’s nothing like your bed’s abyss;

And Lethe dribbles through your kiss

From your mouth’s prison of forgetfulness…

To suffocate my bitter counterpart

I suck the warm narcotic distillate

From the swollen tips of those keen cuspate

Breasts that never hid a heart.

– ‘Lethe’

He was in his early twenties when he met the woman who would dominate his life as mistress and muse. Jeanne Duval – if that really was her name – had come from the Caribbean, trafficked probably, a mixed-race bit-part actor whose beauty had drawn her to the photographer Nadar and a host of other men before she slipped into the poet’s life. “Lethe”, the poem above, characterises much of his relationship with her: passionate, wild, bitter-sweet, sado-masochist, and yet they would keep returning to each other for over 20 years until Baudelaire’s death.

His mother Caroline could never fathom the relationship, writing later: “Oh if you knew!... In her letters, and I have a mass of them, I never see a word of love. If she had loved him, I should forgive her, perhaps I should love her; but these are incessant demands for money.” Jeanne was never faithful – but he knew that, and neither was he – she was in constant need of money, a poor in-between scratcher on society’s sores who had every right to demand what she did because it was that society which made her. As one critic has put it, she was “one who, while embodying the tendencies of modern capitalism to the highest degree, is simultaneously engaged in an inevitably doomed struggle against them”. Baudelaire was engaged in the same doomed struggle, but she kept coming back to him in what can only really have been a pathetic attempt to love the unlovable.

Jeanne was Paris for him: the scintillating, stinking, subtle, changing French capital he spent the majority of his life in; the pleasures he knew there, the diffident friends and literary enemies, the poverty, a lover he loved to hate, the whole fetid world of Les Fleurs du Mal.

When pleasure’s hour is rung,

To crawl, like a sneak, without a noise,

To your body’s treasure trove,

To chastise your lovely skin,

To bruise your forgiven breast,

And to make in your astonished flank

A cut both wide and deep,

And, dizzying height of pleasure!

Between these sister lips,

Brighter and more beautiful,

To jerk my venom there.

– ‘To one who is too happy’

The Flowers of Evil

Among the initial thoughts for the collection of poetry that would make his name was the overall title of “Lesbians”. A handful of poems in the 1857 edition explored lesbian sexuality, but that wasn’t really the point. Lesbians, to the moral outrage of bourgeois France, were both sexual outriders and explorers on the boundaries of gender politics. Baudelaire the poet had a great deal of sympathy for this position. Women rejecting the shackles of the patriarchy were a potent symbol, wild and ungovernable, willing to endure pain for the sake of sensual revelation:

Leaping fearless into bottomless steeps,

And run, sobbing in fits and starts,

Stormy and secret, swarming and deep.

– ‘Lesbos’

Les Fleurs du Mal, as it was published in 1857, is an epic of the modern era. All life is contained in its pages, every sensation – sweet and bitter, beautiful and monstrous – is explored with an anatomist’s scalpel. The inhabitants of a great city, sweating and crawling and screwing and drinking their way to paradise, are the poetic heroes of our time:

Fill up with hookers and crooks in cahoots,

And thieves, who show neither truce nor mercy,

Are soon plying their trade as well,

Forcing sweetly doors and vaults

For a few days’ swag and their mistresses’ junk.

– ‘Evening Crepuscule’

While it clearly had its critics, enough of Baudelaire’s contemporaries recognised what he’d achieved in weaving a tapestry of sensations. The novelist Gustave Flaubert wrote to him “you have found a way to rejuvenate Romanticism… you are as unyielding as marble, and as penetrating as an English mist.” Baudelaire would defend the poetry to his mother:

You know that I have always considered that literature and the arts pursue an aim independent of morality. Beauty of conception and style is enough for me. But this book whose title says everything, is clad, as you will see, in a cold and sinister beauty. It was created with rage and patience.

Here is the first instance of the doctrine of art for art’s sake – for it was a doctrine – and in proposing it the book was little more than an act of revolution. Nine years earlier his affinity with the demi-monde, the Parisian poor among whom he lived and wrote, had led him to the barricades, just as his stepfather, the fastidious General Aupick, was defending the old corrupt regime of the bourgeois King Louis Philippe from his position as head of the military École polytechnique. In February 1848, an acquaintance found the 26-year-old poet not far from the École sporting a stolen hunting rifle as the city exploded in rage. “I’ve just fired my first shot,” he cried. “Down with the regime. Let’s go and shoot General Aupick!”

It’s hardly surprising that the old world of capitalist privilege and the man who’d kept him financially crippled were conflated, each symbolic of the other. For symbols were important to Baudelaire, after all. He understood their power, as the final title of his most famous collection implies. In Correspondences the natural world is a “forest of symbols” in which different senses merge in synaesthetic wonder:

In a dark and deep togetherness,

Vast like the night, grand like the light,

Perfumes and colours and sounds rebound.

There are scents cool as infant flesh,

Sweet like oboes, green like meadows,

And others, corrupted, rich and blest,

Expanding into infinite matter,

Like amber, musk, benzoin, incense,

Which sing of the bliss of spirit and sense.

– ‘Correspondences’

The painter of modern life

Colours stimulate the sense of smell, images contain sound, sounds suggest scents. In fact, Baudelaire was as passionate about the role of visual arts and music in modern life as he was about poetry. He first came to the public’s attention in reviews of the Salons of 1845 and 1846 in which he elevated the critical form to classic literature. His concerns, paradoxically at first glance, seem to prioritise the ephemeral, the everyday in art over the symbolic, the eternal, but that ignores what he would later articulate: “beauty is always and inevitably compounded of two elements”. He went on:

On the one hand, of an element that is eternal and invariable, on the other of a relative circumstantial element, which we may like to call… contemporaneity, fashion, morality, passion. Without this second element… the first element would be indigestible, tasteless, unadapted and inappropriate to human nature.

The best art is, therefore, both timeless and instantly recognisable on some level – what he understood as modernity. Baudelaire came to know artists well, well enough to be seated among a group of painters – Whistler, Manet, Félix Bracquemond – in Henri Fantin-Latour’s Homage à Eugène Delacroix, and well enough to influence the sort of subject matter they chose. A good friend of Baudelaire, Édouard Manet wanted so much to be the painterly equivalent of the poet. When he submitted his early masterpiece The Absinthe Drinker to the Salon of 1859, clutching the poet’s arm for reassurance as he went to deliver it, it was an attempt to get to grips with the modern urban world through Baudelaire’s own metier.

Stumbling and elbowing the walls like a poet,

Without a worry for his vassal snitches,

His heart bubbles with grandiose schemes.

He takes oaths, sublimely dictates laws,

Floors the wicked, gives their victims what they need,

And under the firmament’s suspended shade

Gets drunk with the splendours of his own worth.

– ‘The Ragpicker’s Wine’

The painting was rejected as not a worthy subject for the official salon. Manet’s figure in his dandified rags could be Baudelaire himself, he is certainly an apparition from Baudelaire’s poetical imagination, a distracted phantom which has emerged momentarily from the crowd, livid, his pores swampy with alcohol, defying us not to turn away; he is Baudelaire’s modern hero who has cast his empties out at us and stands, uncertainly against a ledge (the glass of absinthe is a later addition), eyes glazing, the wet of dribble on his chin, saying “yes, I am a drunk, but I at least have seen paradise”.

A few years earlier, in 1845, Baudelaire had wondered why no contemporary painter had recognised that “...the heroism of modern life surrounds and presses upon us”. He predicted that “the true painter for whom we are looking” would “snatch its epic quality from the life of today and... make us see and understand, with brush or with pencil, how great and poetic we are in our cravats and our patent-leather boots.” Baudelaire possibly hoped that his hero, Delacroix, would take up the challenge, but what’s curious about this prediction is that the one artist who to posterity looks like the painter of modern life is all but ignored in his critical writings.

Manet knew Baudelaire well. He chose as his subjects just those crowds of frock-coated and muslin-clad bourgeoisie, the artists, the writers, the courtesans of the boulevards, the rag pickers and street musicians, the ups and downs of 1860s Paris. Baudelaire appears among the fashionable mêlée – that crowd again – in Music in the Tuileries. Manet produced a not-entirely sympathetic portrait of Jeanne Duval, whose petticoats are heroic, indeed, and planetary in scale. He’s unapologetically modern at a time when most artists, including Delacroix, are harking back to some never-never Middle Ages or breezy antiquity. Here are cravats and patent-leather boots galore, not to mention crinolines, “watered silk à l’antique, or satin à la reine”. But what Manet lacked, in Baudelaire’s estimation at least, and Delacroix understood implicitly, was a grandeur of vision:

It is the invisible, the impalpable, it is the nerves, the soul… [Delacroix] has done this with the perfection of a consummate artist, with the rigour of a subtle man of letters, with the eloquence of a passionate musician… the arts aspire, if not to replace each other, at least to lend one another new powers.

Baudelaire, who prized imagination before mechanics, believed that art should be created using mnemonics: images sprung from recollection, the result of a flâneurial rummaging about the drawers of Paris’s high and low societies, would bring a greater spontaneity to composition than the laborious precision demanded by copying a model. Art should also lend and borrow from each of the senses. He would write in an early appreciation of Richard Wagner that his notion of the total artwork was “the meeting point, the coincidence of several arts – as art in the fullest sense of the term, the most all-embracing and the most perfect.”

So when Baudelaire came to publish his most comprehensive essay on the subject, The Painter of Modern Life of 1863, which begins with those ruminations on the nature of crowds, it’s surprising he didn’t have Manet in mind, but a lesser artist, Constantin Guys. A 100 years later, Guys would have been a photo-journalist, snapping war zones and Saigon fleshpots. As it was, his fascination for the everyday – soldiers and courtesans, street scenes and troop movements – captured in rapid sketches lightly washed with colour, would have a strong influence on the next generation of artists of the Impressionist movement: “He’ s gone everywhere in search of the ephemeral, the fleeting forms of beauty in the life of our day, the characteristic traits of what we have called ‘modernity’… he’s succeeded in distilling the bitter or heady flavour of the wine of life.”

‘The soul of wine’

The journalist Maxime du Camp first met Baudelaire in 1852 when the poet visited his lodgings. Baudelaire declined tea and spirits, stating “I only drink wine”. He proceeded to polish off a bottle of Burgundy and a bottle of Bordeaux – “in large gulps, slowly, like a ploughman – asking his host to have a carafe of water removed –”I don’t like to see water”. At the time he’d written a short piece “On Wine and Hashish”, which he would later revise into one of his most poetical and instructive works on the subject, Artificial Paradises. These alternate states were morally neither good nor bad but a place of potential, of latency; as a state very much in the moment but also outside that moment, they were, in that sense, the definition of modernity.

Published in 1860, the first part, dealing with hashish, winds seductively through the different stages of experience, culminating in “an extraordinary acuteness of all the senses. Smell, sight, hearing, touch; all have an equal part in this progress. The eyes gaze at infinity. The ears perceive sounds which are almost indiscernible… External things assume curious appearances… They grow distorted and transform themselves.”

Symbolism, Wagner’s total artwork, the flimsy and the profound, it’s all there, in one good trip. But Baudelaire was not a fan of the drug, warning against disturbing “the primordial conditions of … existence” and destroying “the balance of… faculties with the surroundings in which they are meant to move”. Opium, the subject of the second part of the book, fares no better, but for Baudelaire there is far more of a personal recollection: like Thomas de Quincy, whose Confessions of an English Opium Eater inspired the text, Baudelaire had become reliant on laudanum – a distillation of opium often taken dissolved in a double whammy of wine – as an anti-depressant and to dull the pain of recurring stomach cramps, probably the result of alcohol consumption.

In the earlier essay, Baudelaire compared the merits of hashish and wine – “they have something in common: the extraordinary amplification of man’s poetic nature”. But he comes firmly down on the side of the grape over the hemp. “Wine exalts the will, hashish destroys it. Wine is physically beneficial, hashish is a suicidal weapon. Wine encourages benevolence and sociability. Hashish isolates. One is industrious, in a manner of speaking, the other essentially indolent. What, indeed, is the use of working, labouring, writing, producing anything whatsoever, when paradise might be attained without the least effort?” A section of Les Fleurs du Mal is dedicated to the pleasures and comforts of wine:

The throat of a man worn out by work,

And his hot breast is a sweeter nest,

Where I’m happier than under a cold cork.

– ‘The Soul of Wine’

Even in excess, wine has its merits. In the biography he published of American writer Edgar Allen Poe – as preface to his translation of Poe’s short stories – he celebrated his subject’s alcoholism, before the word had been invented. Sensing a kindred spirit whose ‘drunkenness was a mnemonic means, a method of work, an energetic and deadly method, but one that fitted his passionate nature’, he was not unappreciative of the fact that Poe’s dark, Gothic imagination was in large part due to his willingness to submerge himself in addiction, almost for our, that is his readers’ benefit: “[A] part of what is today the source of our enjoyment is what killed him”. It’s a distinctly pagan thought which reminds me of those prophets and sibyls of old who found clarity in hallucinogens. There’s a crazy logic to it: strong drink could be an aid to creativity, summoning up monsters later to be distilled into something supremely, heroically beautiful. After all, we are never more heroic than when we’re drunk.

And all this may seem like a digression, a shift away from anything serious in a writer’s work, but it concentrates our understanding of another aspect of what it is to be modern. Baudelaire called it spleen, which at the time meant melancholy – what we would call depression. To live in a society in which a belief in hierarchy has collapsed leaving only the naked bones of greed, of capitalism, unfairness, inequality is crushing to the soul. There is only distraction – the artificial paradise of drink and drugs – or madness.

‘We’ll wear out our souls in subtle schemes’

A little before the publication of Les Fleurs du Mal, General Aupick died, leaving Baudelaire’s mother a widow once more. There was a mellowing in their relationship, but it was still fraught and twisted with recriminations on both sides, principally about money and Charles’s endless “failures” at leading a conventional life. By the mid-1860s his health was failing and his penury a matter of real concern. He’d finally broken with Jeanne Duval after discovering that the money he gave her she was passing on to a man she claimed was her brother, when he was nothing of the sort. Hounded by bailiffs and still performing moonlight flits from shabby rented rooms, he found himself in Brussels, where his creditors couldn’t reach him and, more importantly, the laws dealing with what could and couldn’t be published were more lax.

But Brussels was not a success. No publishing contracts, disastrously poor responses to lectures – at one he began with the words: “It was in your presence, at my first lecture, that I lost what might be called the virginity of speech. This is, incidentally, no more to be regretted than… the other,” only to realise that a part of his audience was made up of young convent-educated women. Belgium depressed him. He was chronically short of money and ill. And he began to obsess about religion and mortality.

And demolish many a heavy frame,

Before we gaze on that glorious Thing

For which we shake in infernal dreams!

– ‘The Death of Artists’

On a brief trip back to Paris, he found himself at Gard du Nord, having missed the last train to Brussels. He didn’t have the money for a hotel. A young friend, Catulle Mendès, found him there and offered to put him up for the night in his tiny flat. Baudelaire stretched out on the sofa and asked for something to read. He suddenly dropped the book he’d been given and said: “Guess how much I’ve earned in the whole of my working life.” The answer given was 15,892 francs and 60 centimes. Baudelaire laughed. He suggested Mendès put out the lamp, but he continued to talk in the dark, eventually asking his young companion if he knew the writer Gérard de Nerval, who’d recently committed suicide.

‘‘No, no, he wasn’t mad,” Baudelaire became animated. “He was not ill, he didn’t kill himself. No, you must make sure everyone knows, you must tell everyone that he was not mad, that he did not take his own life. Promise me you’ll say he didn’t kill himself.”

Worried, Mendès promised, believing Baudelaire was really talking about himself, and then retired to a fitful sleep. When he woke Baudelaire had gone, leaving a note: “A bientot!” A few weeks later, back in Belgium, the poet suffered a stroke which left him partially paralysed and dumb. The great weaver of words would never speak again. Caroline, his mother, brought him back from Brussels to Paris and placed him with a nursing home near the Arc de Triomphe. For over a year he remained in much the same condition until, in the summer of 1867, his health went into a sharp decline, confined to bed and helpless.

It was the summer of the World’s Fair, and through his window echoes of celebration – marching bands, singing, the clip-clop of dragoons’ horses and, in the evening, drunken merriment, all the sounds of the crowd – drifted in like snatches of poetry or glimpses of paintings. Unable to communicate other than through groans, dreadful bedsores, from long periods of inaction, would cause severe pain every time he was moved. He grew weaker, catatonic. He’d made it clear to his mother that he wanted Jeanne Duval to be helped after his death, but she made no attempt to find her. On the last day of August his mother cradled him in her arms, reconciled at last to her brilliant, furious, gentle son, while he quietly died. “I was murmuring endearments to him all the time, being convinced he could hear me, prostrate and speechless though he was, and could respond.” He was 46.

Not long after, a new edition of Les Fleurs du Mal was published. It’s been in print ever since, translated into numerous languages.

Years before, Caroline and her husband had entertained Gustave Flaubert and Maxime du Camp at the French Legation in Constantinople. Du Camp began to eulogise Baudelaire, not knowing his hosts’ relationship to the poet and that General Aupick couldn’t abide hearing his stepson’s name by this time. Afterwards, Caroline came up to Du Camp and asked: “He has talent, doesn’t he? The young man you mentioned?’

Baudelaire died as he had lived: with supreme irony. Accounts of his last days chime with his own approach to tragedy: odd details, a detached point of view, almost that of a voyeur, but the overall sense of a life lost to indifference is devastating. In one of the “prose poems” published in his last book, Paris Spleen, he borrowed a true story of a young lad that Édouard Manet had employed as an assistant, who was then caught stealing sweets from the painter and threatened with dismissal. Manet returns home that day to find the boy hanging from a nail on the cupboard from which he’d stolen. The painter is horrified, not only with his own heartlessness but at the prospect of telling the boy’s parents. But the mother asks only to keep the rope which her son used to hang himself. The next day, Manet receives a steady stream of letters from his neighbours asking for a piece of that rope. The rope of a suicide was a powerful talisman, apparently:

…and I understood why the mother had been so keen to have the rope and how she meant to find some consolation in losing her son by selling off bits of the instrument of that loss.

Baudelaire had the misfortune to be a great poet at a time when poetry, which had been everything in the generation of Napoleon, of the Romantics, had been replaced for a fickle reading public by the novel, a form, other than in these brief snatches of anecdote, he could never get to grips with. Narrative and character, plot twist and reversal were in demand, and poetry was relegated to passages of description.

Writers like Balzac, Hugo, Dickens now captured the imagination. Gustave Flaubert’s most famous novel Madame Bovary had also been prosecuted for obscenity a little before Les Fleurs du Mal, tellingly without success. Sex in the service of fiction was acceptable, it seemed, but as a mirror to society, in a collection of unashamedly modern poems, it was too much. As it happens, both prosecutions created a demand for the works in question, but Baudelaire’s was a slow burn and only crackled into flame with the younger writers and critics of the 1880s and 1890s, who appreciated all the knife twisting in the heart of a capitalist bourgeoisie Baudelaire’s writing had come to represent. His long-suffering and loyal publisher would write:

Baudelaire’s expected end moved me as much as that of my brother, whom I lost suddenly four years ago… But he is the author of Les Fleurs du Mal, and sure to be remembered as long as the French language is spoken and written.

The last irony of Baudelaire’s ironic life came at the very end. A modest funeral in a church at Passy, near Montparnasse, was followed by a procession to the cemetery. Various friends, writers and painters, admirers, attended both. Théodore de Banville delivered the eulogy, prophetically stating that “the man has just died; the lasting triumph has begun”. Manet followed the cortege and would later begin a painting of the scene, a grand view of the city rising as a theatrical backdrop behind the graveside. A clap of thunder scattered some of the mourners and a downpour of rain glistened on the mounds of soil and the brass of Baudelaire’s coffin as it was lowered to eternal rest beside that of his stepfather, General Aupick, at his mother’s request.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments