The highs and lows of the Premier League in 2021/22

Another year has almost passed and the top flight in England has enthralled, engrossed and made us wonder about the moral state of the game, writes Karl Matchett

An awful lot has happened and been lost since 9 March 2020, some of which is yet to return; some of which may never do so. One cultural cornerstone that happily did make a comeback though, 522 days later: 13 August, the start of this Premier League season and the full, unrestricted return of supporters to stadiums in the competition.

It was vibrant, it was exciting, it was noisy; it was not necessarily a sign of what was to come, as Brentford beat Arsenal to mark their top-flight return and, for one giddy night, sit top of the table. As has ever been the case for football fans, the season opener heralded optimism and enthusiasm, a sunny perspective on the possibility of the months ahead. That went double considering it came on the heels of a (mostly) hugely enjoyable summer tournament.

Where the Premier League offers opportunity, though, it must also provide the other side of the conversation too in controversy, disappointment, even anger.

Such is the nature of elite sport, and more so when the finances and the worldwide coverage on offer make involvement an enticing prospect.

As the Premier League enters its final week of 2021/22, with each of the title, relegation and European berths all still to be decided on the pitch, it’s still arguable that the campaign will end as it started: with off-pitch matters the most real and vital factors for which history will recall the season. Much of it, unfortunately, far from as wholesome or enjoyable as that opening night at the Brentford Community Stadium.

It would be remiss to ignore the spectacular talents that have been on show, the incredible individual matches fans have witnessed and the feats of progress in team-building which, regardless of silverware or spending, give supporters the greatest commodity of all: hope.

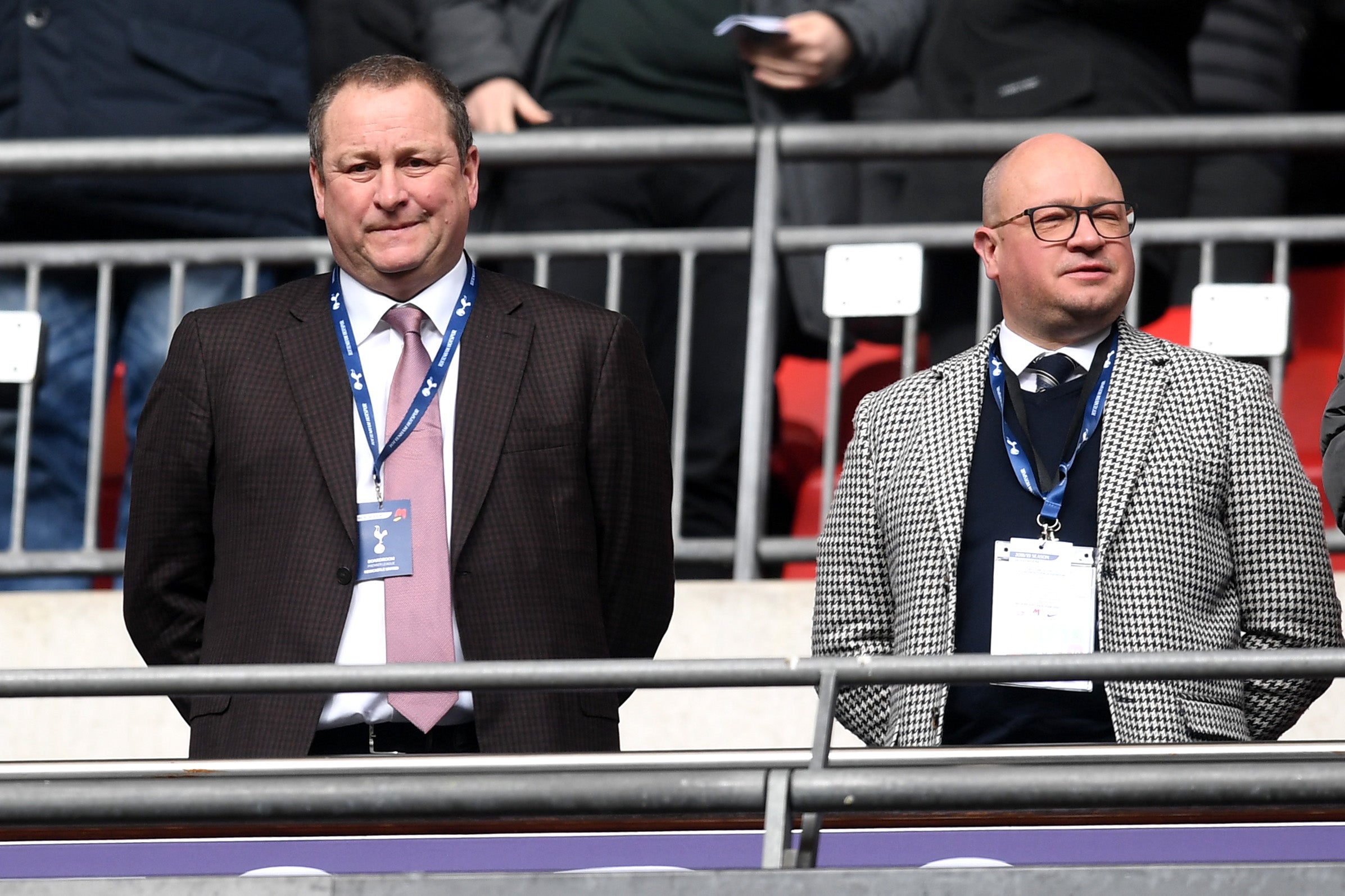

That very same emotion though – or the absence of it – perhaps led to this year’s raging wildfire of a debate: whether sporting values or humanitarian ones should play a decisive role in supporting, opposing or allowing the takeover of Newcastle United. During what was unquestionably the league’s first landmark of the campaign, Magpies fans wanted nothing more than to be rid of their stifler-in-chief, Mike Ashley. St James’ Park had been bereft of joy, adventure or scope for improvement for too long under his stewardship, and fans wanted a change. Any change.

When it arrived in October though, it came with just about equal numbers of “pounds in the newly minted war chest” and “morality strings attached”, with the Premier League pushed front and centre in only the latest example of sportswashing in football. The league countered those recriminations by insisting they had “received legally binding assurances that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will not control Newcastle United Football Club”. Fast forward a mere seven months and the leaked new away kit on the horizon for the northeast club, which mimics the colours and style of the Saudi national team shirt, looks an incredible coincidence, then.

There are further off-pitch problems too: societal ones, but viewed through a footballing lens.

As recently as the penultimate weekend, arrests were made of Burnley supporters making “discriminatory gestures”. Earlier in the campaign, Liverpool fans were urged to refrain from repeating a homophobic chant aimed at Chelsea, while Man City supporters were then heavily criticised for booing during a minute’s silence at Wembley for the 97 supporters who died at, or after, the Hillsborough disaster. Arsenal’s bench reported racial abuse back in December, while a Manchester United fan was arrested after racist comments made during a match too. There have been more besides, even without delving into the cesspool of football social media.

Some of these terrace indiscretions are lingering holdovers from an age when they were commonplace, now bypassed but with some stragglers yet to keep up with changed times. Others are simply moronic, ignorant and purposely vile. None are acceptable.

Dismally, the term “unacceptable” – and many others besides – may also extend to a number of players.

Mason Greenwood remains on bail, with a court date expected in June after being arrested on suspicion of rape and assault of a woman, along with suspicion of threats to kill. Benjamin Mendy faces a trial in July, having been arrested and spending four months in jail, charged with seven counts of rape, which he denies. And in Scotland, David Goodwillie’s loan switch from Raith Rovers to Clyde caused a huge backlash – including the women’s team quitting the club – after he was ruled to be a rapist in a civil court in 2017. There is a limited amount clubs can do during ongoing police investigations, but internal questions must be asked over processes, timing of player suspensions and victim support.

More on the football matters, there’s a difference between individuals accused of outright violations and the moral discussion over just how much separation there must be before organisations – clubs – and the people who follow them are responsible for others’ transgressions, large or small.

Despite claimed-and-rejected associations with a regime responsible for human rights violations and invasions, it’s entirely possible that Newcastle and the Saudi Public Investment Fund will take second place in grand-scale, seismic shifts when it comes to Premier League ownership changes.

Of more intrigue to many is Chelsea. The timeline of it all moved so improbably quickly, and amid a backdrop of enormous social uncertainty on a far wider scale, that it has been difficult to absorb exactly what the forthcoming departure of Roman Abramovich from English football may lead to. Just as people in general, football fans or otherwise, were getting to grips with how to live in a post-Covid country and a cost of living crisis, Russia invaded Ukraine and caused an entire raft of new knock-on effects. One was for Abramovich to learn of the likelihood of sanctions being placed against him and his assets.

We are now only weeks away from Todd Boehly and his consortium taking over, and there’s no telling how that will go, but Abramovich’s time was a defining era in English football. It sparked discussion, animation and jealousy, but so too a rise in spending, in stardom and in silverware elsewhere.

It inspired, or perhaps forced, a number of clubs to find ways to compete; if not by strength of finances, then finding investment from elsewhere or creating ways to use more limited resources in more impressive ways. Several of the best-fought and most exciting rivalries in the modern era arose at least in part as a response to Abramovich taking over at Chelsea – yet the Blues’ boardroom is far from the only major fallout as a result of Putin’s warmongering.

Days after the club was put up for sale, main shirt sponsor Three suspended its deal with the club over Abramovich’s sanctions. Elsewhere, Everton closed ranks and severed all ties with another sanctioned billionaire, Alisher Usmanov – including ending sponsorships with three companies he had links to.

While those in suits scrambled to correct their dubious decisions in the first place, it’s notable that the actual fabric of the football world – the players, the supporters – was quick to show empathy and understanding to those most affected: from Andriy Yarmolenko being applauded on to the pitch after compassionate leave, to Vitaliy Mykolenko and Oleksandr Zinchenko’s pre-match embrace at Goodison Park, and Brighton playing in their yellow-and-blue away kit on home soil, football up and down the land showed solidarity with Ukraine and its people.

Perhaps that’s a reminder, perhaps that’s the point.

Ultimately, the people are what make football what it is. Those most involved, most affected by the sport’s ups and downs, remain those who put in not millions of pounds but millions of moments throughout their lives, absorbing each weekly result as though it’s the last one that will ever matter and fiercely defending the sovereign republic of Whatever Team They Support FC.

That’s what will make 2021/22 pleasurable, forgettable or utterly memorable for each group of fans.

Take those at opposite ends of the progress spectrum. Manchester United came into the campaign as runners-up, expectant and confident and armed with a returning icon – among more than £120m of new recruits.

The season has been an unmitigated disaster.

With no plan, no progress and one dressing room crisis after another, the Red Devils’ failure to recognise the falseness of 20/21 and the changing landscape of what’s required in elite recruitment has left them further off the pace than they have ever been in the Premier League era. Even if they finish sixth, versus their lowest of seventh in 13/14, the gap to the top then was “only” 22 points – this year it’s a minimum of 29 and as many as 35. Both position and points tally highlight how wrong they’ve got it, how much work lies ahead and how many supporters have been pushed to the brink with their patience.

By contrast, Crystal Palace and Brentford will finish in mid-table, maybe both in the bottom half, and yet both fanbases will be nothing short of ecstatic.

There have been runs of games where wins were not forthcoming, times when maybe the Bees feared a relegation scrap. But the progress is undeniable, the togetherness of team and supporters obvious. Christian Eriksen’s return to the pitch in the striped red and white is another testament to the feel-good side of sport. It’s clear a common directionality does wonders for a football club – and it’s perhaps the south London side who can lay claim to having most “buy-in” of all.

The end of last season heralded the end of a fairly dismal time at Selhurst Park; with summer came a squad overhaul, new manager and a world of exciting possibility, in part through a far more youthful squad. Michael Olise might be the headline act for style and potential, but it’s hard to beat the brand new central defensive partnership of Marc Guehi and Joachim Andersen for an example of excellent, thought-out, reasoned recruitment.

Remaining on an individual level, the usual awards and arguments for the top-flight’s best player will, as is often the case, be split not just by favoured team but by time of year.

Jarrod Bowen’s stock has maybe risen highest this term across English talents, while Bukayo Saka has proven not just his technical excellence but his mental resilience, bouncing back from Euro 2020 penalty heartache to play a central role in Arsenal’s resurgence.

Mohamed Salah was out on his own in the opening months, clinical and consistent and scoring goal of the year contenders weekly at one stage. But while his form dropped off post-Afcon, Kevin de Bruyne’s has skyrocketed. Assists aplenty and a four-goal haul – netted after voting took place for the Player of the Year award, by the way – have seen the Belgian spearhead Man City’s incredibly consistent title defence.

Once more, it has been the Etihad club and Liverpool who have set the standards on and off the ball, with relentless territorial domination game after game matched only by the incessant rate at which they rack up points.

They continue to push the boundaries of elite performance domestically, while also at least running it close on the European stage.

The Reds, heading into the final week of the season and still chasing a scarcely credible quadruple, may yet triumph in Paris to register a seventh continental success to go alongside a domestic cup double. The fact they were genuinely in the running for such a haul of trophies at all, let alone until so late in the season, speaks volumes as to the enormous quality and consistency of Jurgen Klopp’s side. The fact Pep Guardiola’s have still been able to maintain at least the smallest of margins ahead of them in the league table only serves to underline City’s own.

While on the subject of the title rivals, it’s maybe worth noting that those from the Etihad appear to feel they are underappreciated, or underloved perhaps, by those outside the club. The reasoning may be fairly simple: despite the trophies, it isn’t much of a story.

Obviously, winning the league title is big for fans of that club. Rightly so. It’s also right that the style play should be acknowledged, and the aforementioned consistency.

But in terms of City being crowned top club – if indeed they are – there will remain a feeling of inevitability and “according to plan” about it, considering the outrageous expenditure. That’s also a large part of the reason they are not lauded for runs deep into the Champions League, but instead criticised for not outright winning it, even though only a single team in a continent of 750 million can do so each year.

Liverpool and City aside, Europe’s latter stages have been the domain of Premier League clubs once more. Chelsea almost reached the semis, before Real Madrid produced their patented turnaround act, while West Ham went to the last four in the Europa League and Leicester City did the same in the Europa Conference League. A nod too to Rangers, north of the border hopes for British football in Europe’s second-tier competition after some sensational results.

While it’s of course positive for home-based fans to have home-based interest at this stage, it does raise the question of whether it’s healthy for European football as a whole to have such a heavy presence from one league. With incoming rules leading to a potential fifth-placed team heading into the Champions League, there’s a good chance the Premier League will benefit yet further. In turn, that’s more income; in turn, the gap between the few and the many could widen. Uefa may be making the problem worse with this move, even factoring in the truth that top leagues usually dominate for a period, then cycle down as others catch up.

The Premier League shouldn’t exactly shrug its shoulders at such issues, but it’s undeniably more of a question for other European leagues to be concerned over.

And there are further big questions to be answered on home soil anyway: do you need a Portuguese passport to get into Molineux now? Did Everton’s pre-game blue smoke really earn them seven points in May? And will Norwich and Fulham ever play each other again, or are they consigned to an eternity of dodging each other in their perpetual acts of annual promotion or relegation?

A nod too to Watford’s abysmal mid-season decision to employ Roy Hodgson, who had no vested interest or apparent capability to keep them in the top flight. He took over with the Hornets two points from safety just past the midway point, having earned 0.7 points per game prior to his arrival. Ahead of their final match they are relegated with just nine points added under his watch, 0.5 per game on average and 12 from safety. He spent far longer waving goodbye to fans of former club Palace than he did to those of his current employers when visiting Selhurst Park.

Yet maybe this is also an era-marker: the crowd of the old guard who were linked with every available job – Steve Bruce, Sam Allardyce, Alan Pardew, Hodgson et al – do now, mostly by individual admission, seem to have taken their final jobs.

Attention for the future instead turns to a new group of younger head coaches with big ambitions and varying reputations: Graham Potter, Steven Gerrard, Eddie Howe, Frank Lampard, Patrick Vieira, Mikel Arteta. Not all will immediately succeed at their current clubs, but as so many moments and runs of form should have taught us this season if not before: it’s not always about the last game.

The journey has to matter. Games along the way must be enjoyed, soaked in, appreciated. Point by point, one late equaliser at a time where necessary, that’s what makes the hope and belief which burns in the chest and makes the next game the one where following through all those darker times will be vindicated.

And for one final weekend, with survival and silverware still on the line, hope will again be the overriding emotion as the 2021/22 Premier League draws to a close.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments