The remarkable life and horrific death of Pier Paolo Pasolini

In 1975 a left-wing film director was brutally murdered on the streets of Rome. No one knows what happened and the authorities aren’t interested in the truth. Kevin Childs recalls a fearless intellectual

Imagine the scene as if it were a movie script. Piazza del Cinquecento, Rome, at night. The big yellow lights, the bulk of Stazione Termini, Rome’s main train station, stretching out into the dark like a great sleeping dragon. A tracking camera, high up on a mechanical crane arm, gives a sweep of the piazza in front, the comings and goings, cars pull up and people get out, some running to catch a late train, others sauntering to a news stand or cafe.

It’s early November, but not too cold. The warm autumn has lingered on.

The camera follows one car, a silver Alfa Romeo 2000GT, low, sporty, sleek, as it comes to a stop on the curb of the piazza by a cafe called Gambrinus. Some boys, 17 and 18-year-olds, hang about outside.

Cut to a mid-shot as the window of the Alfa lowers halfway and the driver peers out through dark glasses – even at night his eyes are sensitive to street and car lights.

Cut to a young man in a T-shirt and jeans, one of the ragazzi di vita, or street kids, who scratch a living stealing and hustling amid the city’s dense and perfumed alleys, picking over the rubbish dumps of the poorer suburbs, the borgate, or letting a guy masturbate them against a garden wall in one of the smarter districts of Rome while the scent of jasmine or stocks thickens the air, all for a few thousand lire.

The camera caresses him in close-up. Strong-looking, handsome rather than pretty, dark curly hair and brown, sleepy eyes. Those eyes lock on the dark glasses and a faint smile of “and so?” passes over his lips.

He knows what’s up and so does the man in the car, handsome himself, angular features, lean and athletic for a 53-year-old. He’s always nattily dressed in a conservative but stylish style. He drops the glasses down on to the bridge of his nose and smiles back. The boy, Giuseppe Pino Pelosi as he’s known around there, takes a step forward and puts his hand on the chrome handle of the car. They speak. The camera follows him as he goes back to talk to a friend watching from the little area in front of the Gambrinus, where some cheap plastic chairs and tables spill over the pavement under a scrappy vine pergola. Then a tracking shot as he passes back in front of the car, opens the passenger door and drops inside.

Slowly the camera draws back a little while the car pulls out, makes a wide arc turn in the street and heads off quickly towards the Porta San Paolo and the road to the seaport of Ostia.

– and even in winter, in streets abandoned to the wind,

Between heaps of rubbish in the shadows of palaces,

there are many – they’re only moments of loneliness;

the warmer, more alive the sweet body

that anoints you with semen and then leaves,

the colder and more deadly the longed-for desert around you…

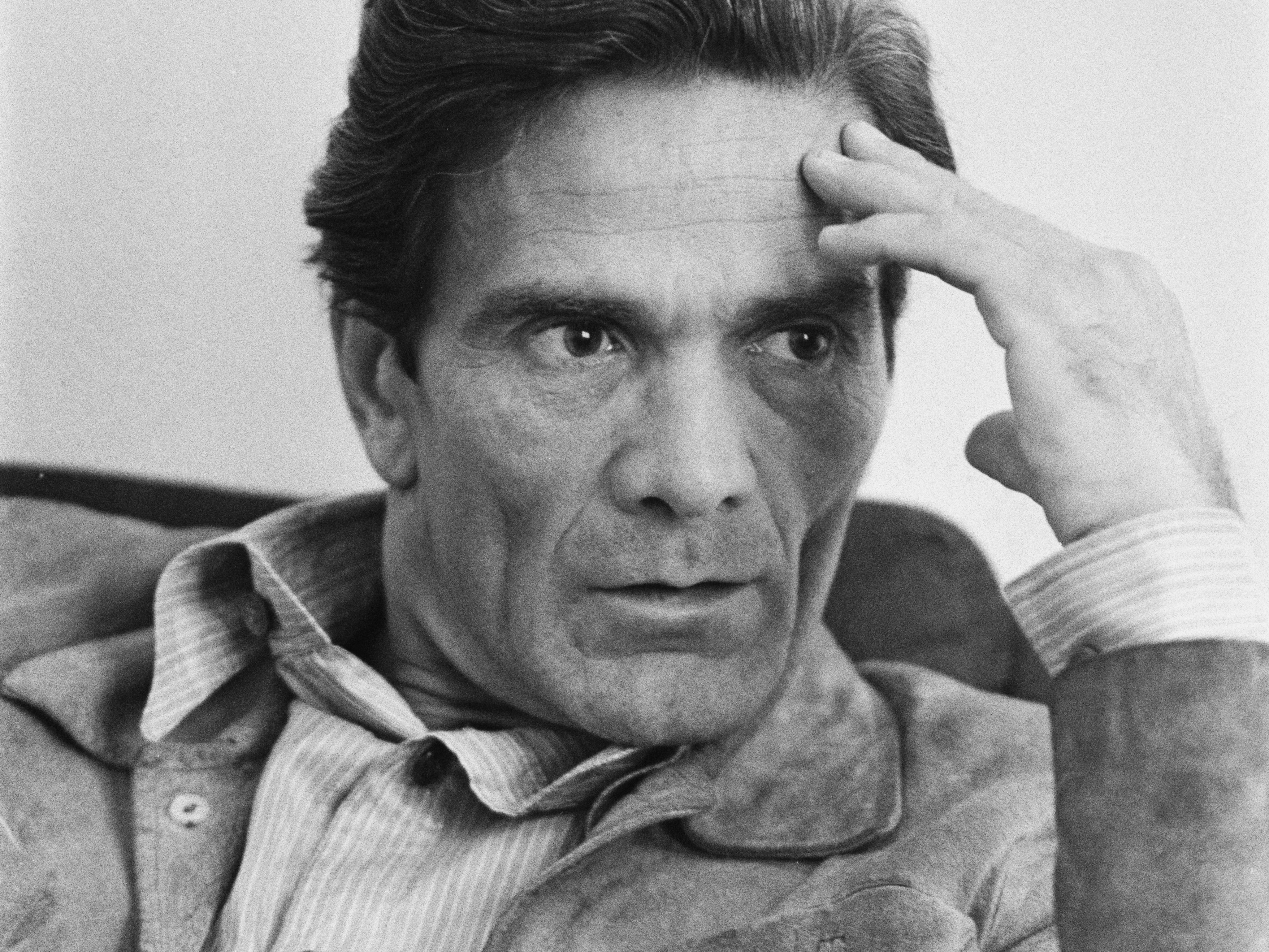

Every biography and critical work that deals with Pier Paolo Pasolini begins with this scene. It seems written for cinema, the sort of work he’d first made his reputation with. Pasolini, one of the most important cinema auteurs of the late 20th century, is himself the stuff of movies. Pasolini the public intellectual whose sharp, sometimes waspish criticism of the march of consumer capitalism meted out in exquisite phrasing among the pages of the more up-market journals was matched only by his ill-concealed contempt for Italy’s left.

Pasolini the homosexual, Marxist atheist whose purist take on The Gospel According to Matthew won the approval of the Vatican. Pasolini, the poet of the rich and richly historic countryside of Friuli, in the north-east of Italy, transported to the ruthless world of mid-century Rome. Pasolini, the neo-realist novelist of the Roman underclass. Pasolini the inventor of sex, or at least the joyous apologist for it in movies such as Teorema, The Decameron, Canterbury Tales and Arabian Nights. Pasolini, who made so many enemies along every fault line of Italian politics because he would not compromise what he believed. And Pasolini, the gentle and kind friend and son who knew only generosity when it came to helping those he loved or wanted to love.

The outcome of that night of 2/3 November 1975 was, it seems, written in the stars, except that no one – not the police, nor the courts (and there were many hearings), nor the journalists, nor the historians and biographers – has ever gotten to the bottom of what happened. We only know that Pier Paolo Pasolini lost his life in a muddy parking lot by the Idroscalo, an old docking place for seaplanes just outside Ostia. His end was terrifying and horrifically brutal.

The countryside around Casarsa della Delizia is still and always was a patchwork of small holdings, fields of maize, tiny vineyards and orchards. In the foothills of the Friulian Dolomites, which sit as a majestic backdrop to so many views, the town is a short way to the east of a broad yellow band of river, the Tagliamento, the dividing line between west and east Friuli. For much of its history it’s been disputed territory, its dialect distinct even from the mainstream of Friulano, a romance language spoken in the mountains thereabouts. Pasolini wasn’t born here – that event occurred in Bologna in March 1922 where his parents, Susanna Colussi a native of Casarsa, and Carlo Alberto Pasolini lived with Carlo’s mother for a few months.

Shortly after, Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister of Italy by King Victor Immanuel III. Carlo Alberto, who had fought in the First World War and saw his prospects only in the army, would enthusiastically embrace Fascism as a means to an end – a solid, respectable career as an artillery officer. With pretensions to minor aristocracy, he also shared the Fascists’ hatred of the left and believed wholeheartedly in a return to order. Neither his wife, nor his children would share his ideology.

With the birth of a second son, Guido, in 1925, Susanna decided to abandon her husband to his itinerant career and bring her family back home to Casarsa, where they lived in the little house attached to the small café-come-trattoria her father owned and in which she’d grown up.

Fast forward through their lives 15 years or so. Italy is again at war, allied to Hitler’s Germany. Carlo Alberto is a prisoner of war in Kenya. Pier Paolo, who has excelled academically in almost everything he’s done, is studying at Bologna University, editing journals on poetry in dialect and receiving glowing praise for his first book of poems in Friulano. Writing poetry was no literary exercise but a way of thinking through whatever troubled him – his verse, throughout his life, was self-referential. Writing poetry in Friulano when the fascist government was doing its damnedest to expunge any diversion from standard Italian was a political act:

will you yet feel

the kisses on your lips

I left there like a thief?

Ah, thieves, the both of us!

Wasn’t it dark in that field?

Didn’t we steal from the poplars

the shadow in your bag?

– ‘Thieves’, c. 1944

By 1943, the Allied invasion of Italy was slowly and painfully making its way up the peninsula. Mussolini was forced to resign in July. Rome was under bombardment from the air and Bologna was threatened. Susanna decided the safest place for her family was in her tiny bit of Friuli, and so Pier Paolo moved back to the flat above the trattoria he’d spent much of his childhood in.

The war didn’t stay away for long. Brother Guido ran off to the mountains to join the republican (but non-communist) partisans, and Pier Paolo, between mooning over a local shepherd called Bruno and keeping up correspondence with friends in Bologna, began drafting and posting anti-German, anti-fascist propaganda which was pasted on to walls around the town. He was even arrested and interrogated by the local police – who ended up apologising to him – and the Gestapo, who did not. But he was freed. By late 1944, the writing was on the wall for the Axis.

In the spring of 1945 came the blow which would stay with Pasolini all his life. In-fighting between the communist partisans of Josip Tito, whose designs for the region included annexing it to a greater Yugoslavia, and the anti-fascist Italian republicans, Guido’s group, turned ruthless and bloody. Even their common hatred of the Nazis couldn’t unite them. At one point Guido was captured by the communists, escaped badly wounded and was captured again. Then in February he was forced to lie in a shallow grave before being shot in the head by one of his captors. He was 19.

Pier Paolo wrote to a friend after he’d received an account of what had happened: “You recall Guido’s enthusiasm, that’s the word that hammers away inside me: he could not survive his enthusiasm… How much better he was than any of us: I see him now, alive, with his hair, his eyes, his jacket and I’m seized by an anguish that is so unspeakable and inhuman.”

On a tram clattering down via Tiburtina from Rebibbia in the north-east of Rome, then a change on to a bus out to Ciampino where he was now teaching at a private secondary school, Pasolini read voraciously. In the early morning shutters crack and crash as they open on the darkened interiors of haberdashers and bakeries, causing him to look up from his book and observe the everyday goings on. The sun slants, already hot in its mote-filled beams, criss-crossing shining electric cables, and sheening sheer off flat-fronted windows. The summer dust is already there in the back of the throat.

Pasolini is 29 and an exile from his beloved Friuli. He had come to Rome to reinvent himself and lick his wounds after a wretched scandal had all but severed him from his previous, happy life. On his way back from work, he would linger by San Giovanni in Laterano waiting for a change of bus, near a pissoir where teenage rent-boys hung out, also waiting, for men like him.

Waiting for a customer films their eyes like a bubble of water: they are eyes crudely veiled in black and yellow, black pupils under blond eyelashes, blond skin blackened by the sun – greased-up haircuts, waves frozen in their heat… kneaded into those eyes, amassed, concentrated, are layers of a Rome without antiquity, wholly modern, everyday, beggarly and of an actuality that burns like a blowtorch at dizzying speed. – ‘Roman Nights’, 1950

By 1951 Pasolini no longer had anything to hide. He’d spent four blissful years teaching literature and classics to boys in a school not far from Casarsa. He’d also begun to develop as a poet, mainly in the local dialect, and had come to realise he too had strong political ideas, formed by Marx but tempered by older mystics – a sort of catholic communism that was not going to win him friends on any side of the political divide. He’d also come to the stark realisation that the post-war settlement in Italy, fuelled by American money and driven by a new party of the right, the Christian Democrats, was nothing but a drain down which every bit of culture, every independent thought, everything, in fact, he held dear in his little corner of Italy would be sucked.

He told whoever would listen or publish his ideas exactly what he thought of the Christian Democrats and their brave new world. He had become a gadfly, a constant thorn in the municipal side, one of those dangerous, radical intellectuals the bourgeoisie so fear, and he was not going to be silenced.

Then the second great disaster of his life fell upon him like a collapsing wall. Pasolini had long recognised his own nature – that he loved men, that he was homosexual and that he had a particular attraction towards boys in their late teens – the pulchritude of youth.

One day at a festival in a nearby town, he’d gone off with some lads to a secluded field. Someone saw them going and told someone else who happened to be a local Christian Democrat party member. The police got involved. The local priests pronounced him an abomination, and a communist to boot. The boys were interviewed, and a charge was drawn up – corrupting the morals of youth, a crime as old as Socrates.

Pasolini would be exonerated on a technicality – the boy he had sex with had been over the age of consent – but this only happened years later. In the meantime, he’d been forced to resign from the school, publicly humiliated in the local press, spat at by neighbours who once thought the world of him and expelled from the local Communist Party. That failure to stand up for him, after he’d thrown in his lot and not inconsiderable talent to promote the communist cause, facing criticism from friends who couldn’t see how he could support the very people who’d effectively murdered his brother, that betrayal was the deepest cut. After a year of braving it out and listening to the increasingly unhinged drunken abuse from his father, who’d come back from a prison camp in Africa an alcoholic, Pasolini and his mother, Susanna, decided to cut their losses and leave.

She had a brother in Rome, Gino, who owned a successful antiques business and whose own reticent style of homosexuality at least lent him a sympathetic ear. And so Pasolini began his life in Rome, the city that would become indelibly stained on his soul. And a pattern for an existence, which hardly changed in 25 years, began.

and at night wander like an alleycat

looking for love . . . I’ll suggest

the Church makes me a saint.

– ‘I work all day’, 1962

Over the next 10 years, from his late twenties to his late thirties, Pasolini would establish himself as one of the most important voices in contemporary Italian poetry and the neorealist novel. In 1955 he published Ragazzi di vita, a picaresque rambling tale of the Roman sub class, following the fortunes, or more properly misfortunes of a street kid called Riccetto from the cusp of his teenage years as a petty thief with a heart just after the Second World War to his later teens as a hustler who tries to go straight but circumstances fail him.

It was uncompromising in language – the characters speak an often down-right filthy version of Roman dialect – and the smart depiction of sexual libido and desire was bound to outrage some. Little tragedies – the friends who don’t make it, the losing of cash ill gotten – are narrated in a sort of Flaubertian matter-of-fact voice which makes no judgements. The tone and subject infuriated the right and the church, which accused Pasolini of immorality, and certain people on the left who thought the lives of such delinquents unworthy of a serious novel. Not for the last time, the distribution of the book was held up while a court decided on its literary merits versus its supposed immorality. The notoriety only helped with sales and when finally released from its official bondage Ragazzi became something of a runaway success.

With the eye of a budding cinematographer, Pasolini mixes grandly poetic depictions of the world of mid-century Rome, in all its gaudy, ghastly splendour, with low-life speech in a synthesis which even the elements seem to reflect:

Part of the sky had cleared completely, and certain big moist stars were shining, lost in its immensity, as if in an endless wall of metal, from which, upon the earth, a few sad breaths of wind whispered.

Even the novel’s devastating denouement is presented as if only fate were involved. Riccetto, now grown up, is unable to save a boy drowning in the river:

At first he didn’t know what was going on, he thought they were having a laugh; but then he understood and he threw himself, slipping, down the slope, but at the same time he could see that there was nothing to be done: to jump in the river under the bridge was like saying you were tired of life, no one could have done it. He stopped, pale like a dead man. Genesio no longer tried to resist, poor kid, his arms flailing about, but all the time not asking for help.

Realising no one has yet seen him, Riccetto decides to run away, thinking “I’m looking after Riccetto” as he does so.

The 1950s were Pasolini’s most prolific years as a poet. He published five collections in the decade from 1951 to 1961 and countless poems in journals and anthologies. The style varied considerably, from modern versions of the old sonnet structure, bound by its own rules, as well as the ubiquitous terza rima, which Pasolini used to drive forward a poem sometimes at a dizzying speed, to wildly free verse, epigrams, odes and seemingly pastoral idyls with a sharply modern twist. Shifting from the almost exclusively Friulian verse of the 1940s to a broader Italian (although often inflected with other dialects), his subjects ranged from the personal – love and cruising, his mother, the death of friends and, most painfully, his brother and then his father – to the grandly historical.

The most important collection was that published in 1957, Ceneri di Gramsci (“Gramsci’s Ashes”), the title poem taking as its premise a visit to the grave in the Protestant cemetery, Rome, of the left-wing philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who had died in prison under Mussolini. The irony of his burial in what he calls a “foreign” cemetery is not lost on Pasolini. His admiration for Gramsci tempered by a sense of loss far greater than the mere body of the philosopher:

(but not for us: you are dead and so

are we, with you, in this humid

garden) shining upon the silence. Can’t

you see? You who rest in this alien

turf, still a prisoner. Bored

Patricians all around you. And only the striking

of anvils from the workshops of Testaccio

comes to you, barely audible in the late

afternoon, between shabby sheds,

bare piles of sheet metal and scrap iron,

where a boy sings lustily, his day

already done, while the rain stops.

– ‘Gramsci’s Ashes’, 1957

The specific (Gramsci’s final resting place) gives way to local colour with the noises emanating from an iron mill in nearby Testaccio and the shop-boy’s song. Finally, the focus shifts to Pasolini himself and his own relationship with the world Gramsci had tried so hard to shape into something more just, more noble, and ultimately failed:

to love the world, it’s only with a violent,

and ingenuous sensual love,

Such as once led me, a confused adolescent,

to hate it if its bourgeois evil wounded

my bourgeois soul; and now divided

– with you—doesn’t the world seem an object

of rancour and almost mystical disgust,

at least the part that is in power?

Yet, without your rigour, I only subsist

because I don’t choose. I live by not wishing it,

as in all the years gone by, loving

the world I hate – in its misery,

scornful and lost – through a grim scandal

of conscience...

Other poetry collections of this time dealt with Pasolini’s relationship with religion, often couched in semi-erotic language and scenarios. Christ sends ‘alien angels’ to tempt him from his path, who take on many guises – a “serious peasant”, a sudden storm that keeps him indoors, a crucifix hanging from a string on a chest ‘I brushed with my hand’. One poem caused a raging furore to fall about his head and the demise of the journal in which it was printed, an epitaph on the death of Pope Pius XII. Without even mentioning the controversy of his utter silence during the time of Fascist/Nazi rule, Pasolini contrasts Pius’s pampered life of luxury and ease with that of a poor old drunk who’d been run over by a tram around the same time he died. The Pope’s greatest fault, his greatest sin was his neglect of the people who lived just a stone’s throw from the Vatican.

In 1959 Pasolini published a follow-up novel, Una vita violenta (“A Violent Life”). A similar tale of the lives of the Roman underclass, the protagonist leads an even more brutal and miserable existence than the boys in Ragazzi di vita, dying alone and unloved in a hospital from a tubercular haemorrhage. Again, the courts were forced to intervene and again, the book sold well as a result.

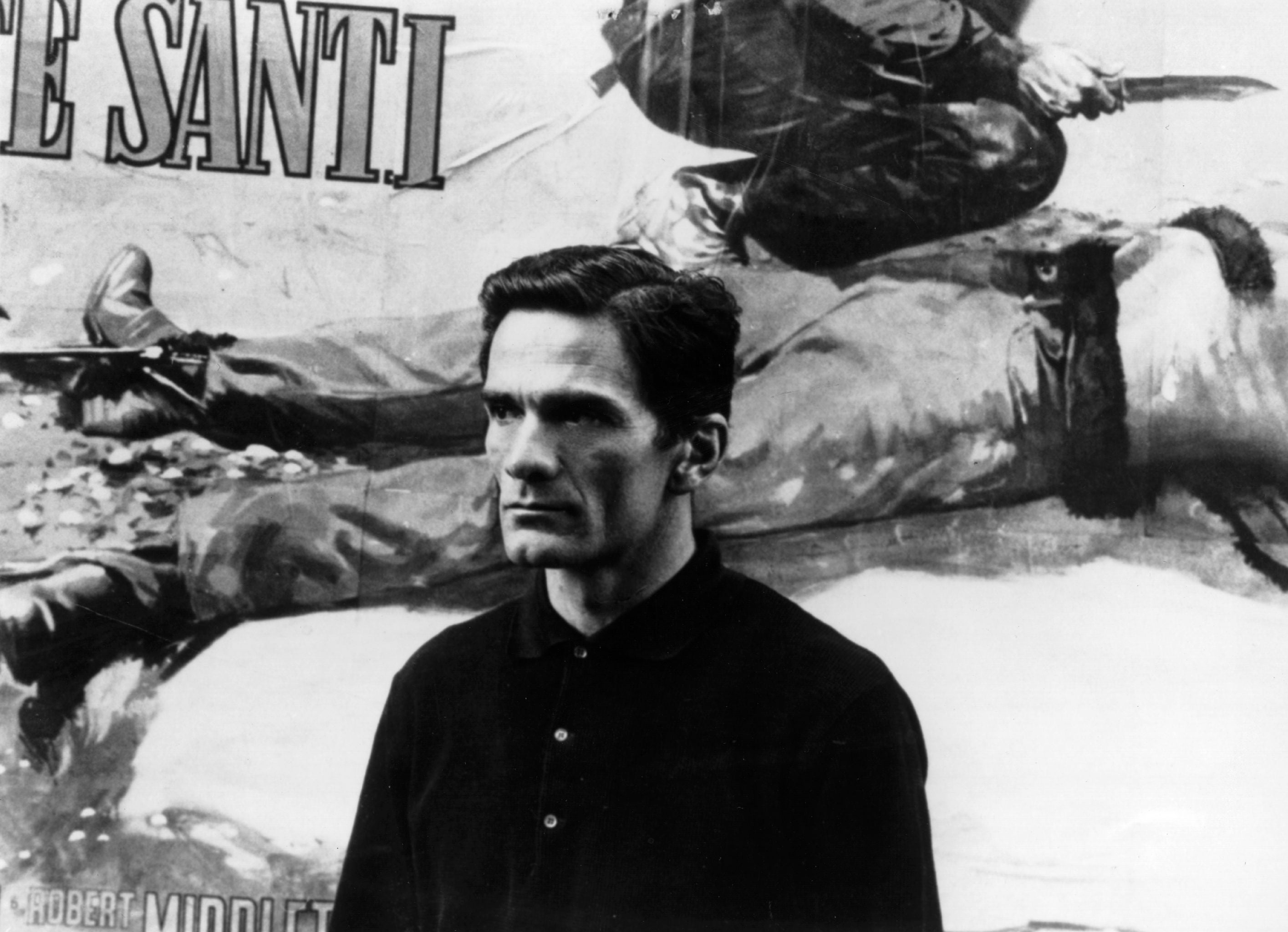

Even before he began to write the novel Pasolini had already launched what would be a long career in movie making. He had become Cinecittà’s go-to writer for tricky dialogue, often in dialect, for low-life characters. In the late 50s he worked with Fellini and Rossellini, eventually writing whole scripts for other directors to film. It was only a small step to become a director himself. And when he did, it was to the Roman borgate, the slums in which those ragazzi di vita lived, he turned once more.

Accattone, released in 1961, follows the unhappy career of a pimp called Vittorio who longs to be rich but has no idea how he will achieve it. He’s fated, in a sense, to follow the lives of all the kids around him. He’s a much meaner version of Riccetto and the anti-hero of Una vita violenta, who beats up on the sex worker from whose earnings he makes a living, eventually stealing a motorbike to escape from the police and getting himself killed when he crashes it. To play him, Pasolini chose a non-actor friend from the slums, Franco Citti. In fact, many of the characters in this and subsequent movies were played by non-professionals. As he explained to a group of film students:

I have an almost ideological aesthetic preference for non-professional actors who themselves are shreds of reality as is a landscape, a sky, the sun, a donkey passing along the road. They’re all elements which I manipulate and turn into whatever I want. . .

Pasolini would film a scene over and over again until what was filmed by the camera corresponded with what he saw in his mind’s eye. In one episode, Citti had to dive off a swimming platform by the Ponte Sant-Angelo in Rome dozens of times until his pose, as he did so, aligned perfectly with the sculpted angels above him.

With now dreary familiarity, the opening of the film was accompanied by a series of petty lawsuits claiming it was obscene, that it misrepresented modern Italy, that it was unpatriotic. In truth, as most of the decent critics noted, it showed Italy how Italy was at the beginning of the 1960s, a society wildly divergent between the haves and the have nots, stuck half-way towards the economic miracle promised for well over a decade by the ruling Christian Democrats and mired in corruption. People on the right didn’t like being reminded.

With the success of Accattone came more films: Mamma Roma in 1962, starring Anna Magnani as a sex worker trying to go straight for her son; La riccotta, a short about a film director, played by Orson Welles, making a film about the Passion of Christ in which the non-actor playing Jesus literally dies on the cross after stuffing himself with ricotta; La rabbia, a hard-hitting documentary using film footage to chart the history of the post-war world; and the first film, also a documentary, to discuss sensibly and without judgement subjects such as divorce, abortion and homosexuality. Each fell foul of Italy’s ludicrously stringent censorship laws according to which if a magistrate in one part of Italy ordered the print of a film impounded, it couldn’t be shown in any other part. Politically motivated law suites could hold up the release of a movie almost indefinitely.

But Pasolini persevered, even when he himself became the subject of police investigations into his private life, including an absurd accusation that he’d held up a petrol station attendant at gun point in order to steal a few thousand lire. Because he wrote and made films about people who did such things, this apparently gave credence to what was merely the ravings of a delusional young man. The right-wing press, of course, had a field-day.

Amidst all the hype, the invective, the threats of violence, Pasolini continued his nightly treks about the city looking for love. He also began a friendship in an unlikely quarter. Giovanni Rossi was the director of the Catholic Church’s Pro Civitate Christiana, an organisation set up in Assisi to promote Christian culture which had veered sharply towards reform with the election of the liberal Pope John XXIII. He and Pasolini over several years would develop a strong bond of respect and friendship and would collaborate on a project that was unnervingly close to both their hearts. As Pasolini wrote to one of Rossi’s underlings:

My idea is this: to follow, at every point, the “Gospel according to Saint Matthew”, without making any script and without cutting anything. I will faithfully translate, in images, without omission to or deletion from the story. Even the dialogue must be strictly that of Saint Matthew, without any explanation or interpolation: because no additional images or words can ever achieve the poetic beauty of the text.

The film that resulted is not only one of Pasolini’s best, it’s also one of his most daring cinematically and controversial thematically. Filmed in black and white, Pasolini had no time for the slick, sculptured biblical epics that had been made in Cinecittà over the previous 10 years. His version of the Gospel According to Saint Matthew would have no dialogue other than what was in Matthew’s gospel, would use non-actors, most of whom were distinctly plain and ordinary looking, and would adopt a series of tableaux often derived from his favourite painters, Masaccio and Piero della Francesca to drive home the narrative. Filmed in poor and deprived areas of Calabria, using ancient crumbling hillside towns to double as Bethlehem and Jerusalem, the landscapes would play as vital and distinct a role as the actors.

Pasolini’s hand-held camera work gives the movie the feel of a documentary, as if from a time before documentaries. That camera work could bring out the strange vulnerability of the girl who played the younger Virgin Mary. His mother Susanna‘s particular look, like carved granite at times, was perfect for the older Mother of God. His Christ was a Spanish economics student who had come to his house one evening to meet the great intellectual only to be asked, almost instantly, if he’d play Jesus in a film. Pasolini’s Christ is a Marxist firebrand, constantly on the move and speaking while he does so. He is silent only when he almost beats up the moneylenders in the Temple, but that silence also identifies a touching vulnerability that appears very modern and affectingly pathetic in the trial and crucifixion scenes.

The church under John XXIII loved the film. The political right hated it and saw in Pasolini’s Gospel everything that was wrong with modern society – and yes there were attempts to have it banned. The left was perplexed as to why one of their number, an avowed atheist, would make such a film in the first place. It won the Venice Film Festival’s Grand Jury Prize and was nominated for three Academy Awards.

Pasolini followed up with a slew of very different films. A version of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King filmed in Morocco starred one of Italy’s great screen actresses, Silvana Mangano opposite Accattone’s Franco Citti. Then a comedy with the king of Italian clowns, Totò, and Pasolini’s new discovery, the 18-year-old Ninetto Davoli, released in English as The Hawks and the Sparrows. And towards the end of the decade, one of Pasolini’s most troubling films to date: Teorema (Theorem).

At a party in an elegant, plush suburban villa somewhere outside Milan, a young man, played by English actor Terence Stamp, can be seen chatting to other young men through a doorway. He’s just arrived as a guest with the family who owns the villa, and one character leans over to another to ask who he is. “He’s just someone we know” is the reply betraying both incomprehension and acceptance.

Stamp’s character in Teorema smiles sweetly through his section of the film while he seduces, or more accurately offers love, to each member of this wealthy bourgeois family, including their conscientious but unhappy maid – played by the veteran actress Laura Betti. The young son, Pietro, longs to rebel but is too well brought up until he shares his bed with the “guest” and is liberated by sex. His mother, the exquisitely beautiful Silvana Mangano again, also loses herself in sex with Stamp ending what we can only assume is a long period of drought in an icy marriage. The ‘guest’ goes on to seduce the industrialist father and his daughter, each liberated in such a way as to suggest that their seducer is rather more than an itinerant young man. “He could be the Devil,” Pasolini told a BBC interviewer, “or a mixture of God and the Devil. The important thing is that he is something authentic and unstoppable.”

Teorema was made and released in that highly volatile year 1968. It’s significant that liberation comes through sex – even the religious Betti is freed by her intercourse with Stamp’s character, rushing off back to her village to be venerated as a mystic. Pasolini’s habitual contempt for the bourgeoisie is notably absent from this film too. We are made to understand the enormity of what happens to their world when they are forced to confront other possibilities and their own animal natures. They go mad, in one way or another.

In a column for the communist journal Vie Nuove responding to a reader’s letter, Pasolini explained that the Marxism he espoused was closer to the reality of religion than the capitalism of the bourgeois ever could be:

The atheism of a militant communist is the flower of religion compared to the cynicism of a capitalist: in the former one can always find moments of idealism, desperation, psychological violence, cognitive will, and faith – which are elements, however dissociated, of religion; in the latter one finds only Mammon.

The consequences of the young man’s visit are both tragic and absurd, consciously so. According to Stamp, at the British premiere “people just laughed, the English are like that.” While in Paris the cinema was swamped by long lines of eager punters, and Stamp had to hide:

The story was out that anyone who touched me was transformed. It made my life wonderful in Italian restaurants but complicated in Turkish baths.

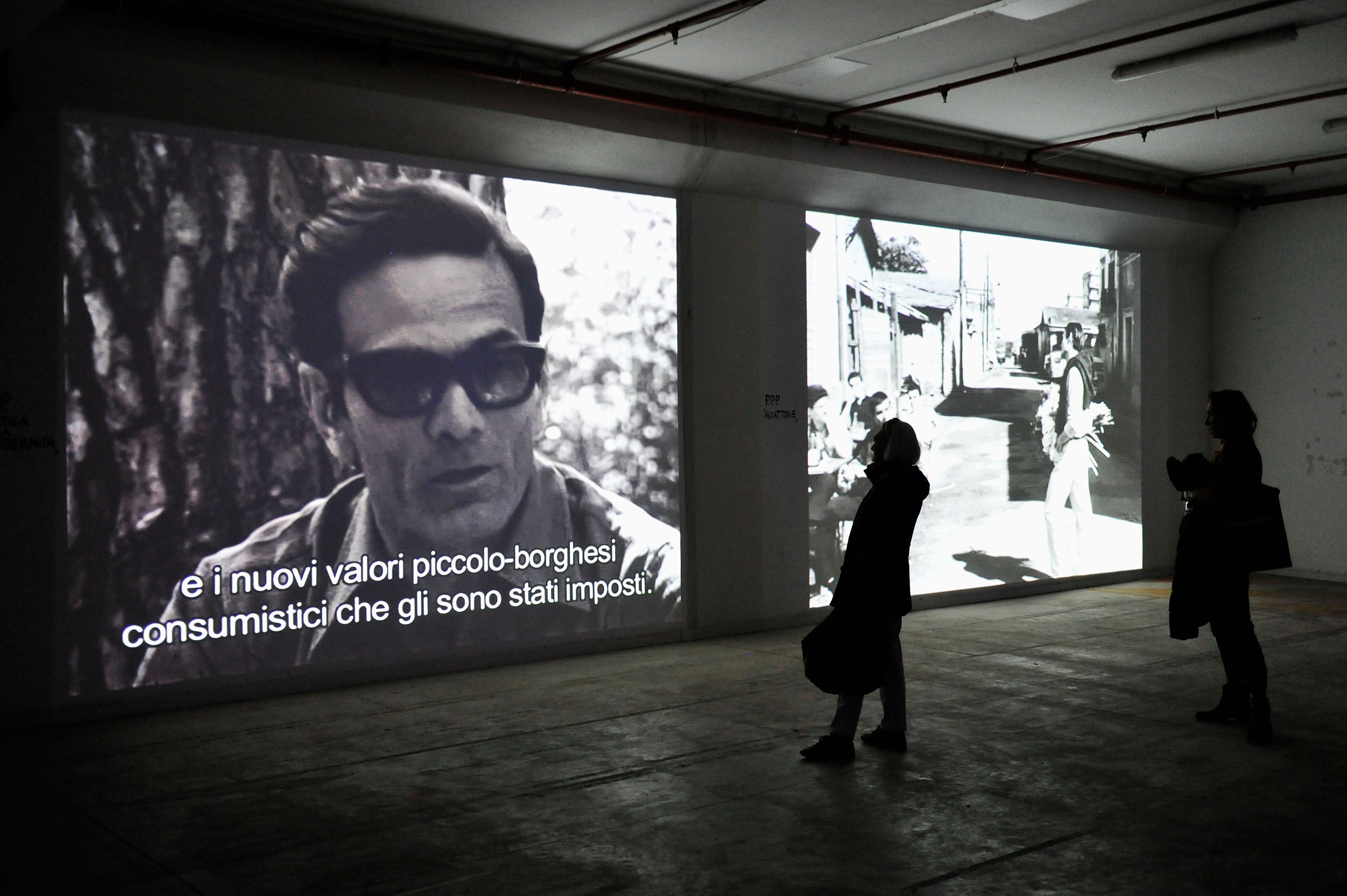

Pasolini couldn’t help being controversial off screen as well as on. While the film garnered the usual hate mail and attempts at banning it, as the streets of Paris and Milan began to fill up with angry students, he spoke scathingly of their efforts and motives. As far as he was concerned, 1968 was a bourgeois revolution instigated by well-off, privileged kids who had little understanding of or sympathy for the working classes of Europe and America. He even expressed some support for the police, sons of the proletariat as they were, who were at the blunt end of violent clashes. Rich kids scrapping with their fathers, whose roles they will eventually adopt, was how he characterised it, while the poor do their dirty work. It won him no friends among left-wing youth groups, even if he had a point. “Stop thinking about your rights,” he wrote in one poem, urging the students to forget about the idea of power: “That’s just liberalism: leave it / to Bob Kennedy.”

Rather than engage artistically with the phenomenon of 1968, Pasolini chose once again to retreat into myth, but a myth that is even more brutal and savage than the tale of Oedipus. The idea of making a film based on Euripedes’ Medea had probably been in Pasolini’s mind since his earlier foray into Greek mythology. But when his producer, Franco Rossellini, suggested Maria Callas as its star, and managed to reel in the great opera diva – her reticence was based primarily on how much she had hated Teorema – the project came alive. And when they met something clicked: between the greatest opera singer of the time and Italian cinema’s greatest bête noire something like a love affair blossomed, entirely unphysical but manifested in a connection that helped immeasurably with the filming. He made drawings of her out of found materials and wrote beautiful letters:

… bringing with you that scent from beyond the tomb, you sing arias composed by Verdi that run blood-red and that experience (without a word being said) teaches sweetness, true sweetness.

For once Pasolini had a sizeable budget and so locations as far flung as Cappadocia in Turkey, Aleppo in Syria, the Venetian lagoon and southern Italy formed the backdrop to the drama. Callas was bedecked with what a critic called “pagan jewels”, which on one occasion caused her to faint in the Turkish summer heat. She apologised for “being so stupid”. His Jason was Olympic athlete Giuseppe Gentile, in his only acting role, and he was skimpily dressed in the shortest of tunics in stark contrast to Callas’s heavy, enveloping robes.

The film is full of ideas – some critics thought too many – and is a palimpsest of where, philosophically, Pasolini was at. In a significant speech put into the mouth of the old centaur Chiron, who acts as pedagogue to the young Jason, the world of the movie – and by extension everything – is expressed in terms of pure mythology with nothing of history in it, nothing of reality. In this world everything is shadowed with meaning:

All is holy, all is holy, all is holy. There is nothing natural in nature, my boy, keep that in mind. When nature seems natural to you, all is over – and something else will begin. No more sky! No more sea!

In a remarkable prefiguring of the modern green-left, here and elsewhere Pasolini predicted how the seemingly unstoppable advance of consumer capitalism would eventually wipe out the planet, and that the only way to counter this devouring was to retreat into myth and symbolism, to endow the slightest thing with “holiness” and thereby, it was hoped, save it. It was a critique not only of the right but also the left which had become as obsessed with productivity and its means as any factory-owning boss. Only ancient worlds such as that represented by Medea’s people and culture and the ‘peasant’ heritage of Callas herself, with all its cruelty and hierophantic numinosity is real.

Pasolini was not done exploring the pre-industrial world. His next three films, made and released between 1971 and 1974, all took as their premise medieval collections of stories and fables. They would be joyous explorations of the vital, the seeming mythical time when love was all consuming and sex uncomplicated by morality. The worlds of Boccaccio and Chaucer, the compilers of A Thousand and One Nights would help reflect, in a semiotic way, the flow of Pasolini’s own feelings, about the world, about his love affair with that reckless protege, Ninetto Davoli, and its abrupt ending half-way through the filming of Canterbury Tales, and about his own response to the so-called permissive society of the late 60s and 70s. This Trilogy of Life, which he would apparently reject almost as soon as it was done, would also represent Pasolini’s most successful – in terms of critical and box-office response – films of his entire career.

There is nudity, both female and male, full-frontal, there are glimpsed erections, bawdy jokes and orgiastic ceremonies. And sex – untrammelled, unapologetic, tender, sometimes violent, between men and women, women and women and men and men. Not just the desire of it but the physical act is the driver for a way of being that is both as old as the hills and new, almost like a revelation. Sex and nudity are as holy as any other natural thing.

Beneath the surfaces of the first two films, The Decameron and Canterbury Tales, lies a cynicism about the merchant class which stands in for modern Italy’s bourgeoisie. Pasolini has even more to say about the church in tales of randy monks, even randier nuns and hypocritical priests. For wealthy parents the price of their children’s sexual freedom is always monetary, if not also social advancement. But the sheer joy and exuberance of this time before time translates – contaminates to use a word Pasolini liked – tragedy and comedy with the essence of each other.

All three films are episodic, following the styles of their sources. In The Decameron Pasolini dispenses with Boccaccio’s meta-narrative centred on the Black Death and replaces it with a linking story of a painter, perhaps intended to be Giotto, slowly making a giant fresco for a church in Naples. Pasolini himself plays the painter. He also plays Chaucer at the centre of the narrative structure of Canterbury Tales. As writer and director, he is literally puppet master too.

When he came to make the last of the Trilogy, Il fiore delle mille e una note – promoted in English as Arabian Nights – the longer view between Pasolini’s own time and the subject of the film allowed him even greater freedom. Arabian Nights is an exquisite paean to love and sex. Its locations from Nepal to Morocco via Iraq, Yemen, Turkey and, yes Italy, are decorative backdrops to a cast of beautiful people headed by the joyously sexy Ines Pellegini as the slave girl Zumurrud and the bewitchingly luminous Franco Merli, another Southern Italian find who shone brilliantly for a short while on the screen, as her lover Nur Ed-Din. Their characters, who find each other in the movie’s opening sequence only to be parted for most of the rest of it, are both innocent and resourceful as their adventures throw seemingly insurmountable obstacles in their path.

As is the way of fables which require no rationale, they re-encounter one another in a far-off city where Pellegrini, disguised as a man, has become king. Thinking this mysterious king wishes to rape him, Merli resigns himself with the observation, “don’t hurt me too much”. The reveal – as sexually explicit as anything else – prompts another poetic moment from Nur Ed-Din, the last lines in the film: “What a night! The beginning was bitter but how sweet is the end.”

Pasolini famously rejected his Trilogy in 1974, decrying its championing by proponents of permissive culture as both missing the point and placing culture in the ranks of just another commodity. Permissiveness was liberal bourgeois toleration by any other name, and Pasolini was having none of it. When he would make another film – also starring Merli who may have been replacing Davoli in the director’s affections – it would be undeniably beautiful, like Arabian Nights, but also horrific to the point of being unwatchable.

Salò or 120 Days of Sodom would be Pasolini’s last film and is as dark as the place Pasolini believed Italy, and for that matter much of the western world, found itself. It’s almost anti-permissive. The original story is by the Marquis de Sade: four wealthy men, representing the church, the aristocracy, the judiciary and business, kidnap a group of young men and women and subject them to an increasingly frenetic and dangerous series of sexual and physical abuses, culminating in torture and murder. Pasolini’s genius is to update this to the last year of the Second World War, setting it in the dying days of Mussolini’s fascist regime centred on the so-called Republic of Salò on Lake Garda.

As the allies advance Pasolini’s quartet retreat to a beautiful villa on the lake with four Madames and a group of teenagers, many stolen from opposition families, and there, subject them to sexual and physical humiliation. A more excoriating denunciation of the inhumanity and moral degradation of fascism couldn’t be imagined. What was so difficult for his contemporaries to accept, however, was the idea that this peep hole on the past was a panorama of the present, as much a warning about the rise of the new right as it was a condemnation of the old one.

If nudity in the Trilogy of Life is an exuberant celebration of the holy, in Salò it is a symbol of vulnerability and humiliation as well as innocence – it’s no coincidence Pasolini cast Merli as one of the most prominent victims. An anecdote told at the time concerned a scene in which the four “masters” judge the buttocks of their captives. The victor, as it happens Merli, is to have the privilege of being shot. When a pistol was put to his head, Merli was so freaked out the filming had to be stopped. Had Pasolini gone too far, or did the memory of something else terrify the young actor?

Pasolini put every ounce of sensuality from his considerable palette into the filming of Salò, even the murderous scenes at the end are shown as if through the long lens of a pair of binoculars creating the impression that these events are not happening in real time. Visually all is shimmering and cool fire even if you have to turn away from it. But there is a humanity at the core of Salò. The young guard who finds love with the black servant (played by Pellegrini), the boys and girls who find each other in the night in small acts of rebellion, the piano player who cannot take it anymore and throws herself from a high window, and the two boys who at the end, just tired of their roles as facilitators to murder, put on a foxtrot and begin to dance together in a scene that is so sweet you almost forget what you’ve been watching.

One of Pasolini’s last poems was addressed to a young man, an avowed fascist, perhaps someone he may or may not have met, or perhaps standing in for so many young men and women in Italy at the time. The controversy surrounding his every appearance in the 1970s was often the result of attacks, sometimes physical, by gangs of far-right youths in the foyer of a cinema or from the back of a packed lecture theatre. The abuse, centred on his sexuality, his politics, his love of beauty deemed degenerate, was constant. And yet Pasolini carried on with a dogged determination that seems both naïve and pedagogic.

Written in Friulano, a final return to where it all began for Pasolini, a return to his youth, the first line of the poem seems to affirm it will be the last. He caresses the youth with words, trying to impart some understanding of that ‘holiness’ in all things, a love for the poor because they are poor, for ‘the dialect they invent every morning / so no one will understand them’, a love for life and a rejection of violence.

Weight onto your shoulders.

I can’t anymore: none would understand

the scandal...

Take this weight, boy, even though you hate me.

You should carry it. It burns brightly in the heart.

And I shall walk on, lightly, always choosing

life, and youth.”

– “Goodbye and Best Wishes”, c. 1974

At about 11 pm on that night of 2 November 1975 Pasolini and Pino Pelosi were driving along the viale Ostiense. They stopped in a trattoria because Pelosi was hungry. He ate a bowl of pasta with tomato sauce. Pasolini drank a small glass of beer – he’d eaten already with Ninetto Davoli earlier that evening. Then they carried on towards Ostia and the sea, coming to a halt in a small parking lot by the Idroscalo beach. There was a scrappy playing field next to the car with a rotten fence, and a ramshackle building still in the process of construction, a tiny illegal house, the first of many, which would allow its owners a breath of sea air at weekends.

What happened next we will never know. Pasolini’s body was found the following morning around 6.30 by the owners of the house. One of them, glorying in the name of Maria Teresa Lollobrigida, told the press later:

I was the one who found the body… When we got here I noticed something in front of our house. I thought it was rubbish and I said to my son Giancarlo, “But just look at these sons of bitches who come and throw rubbish in front of the house”. I went over to see how I could clear it up and I saw it was a man’s body. His head was cracked open. His hair was all smeared with blood. He was lying face down with his hands under him. He wasn’t well dressed. He had on a green sleeveless undershirt, blue jeans dirty with car grease, brown boots that came to his ankles, a brown belt.

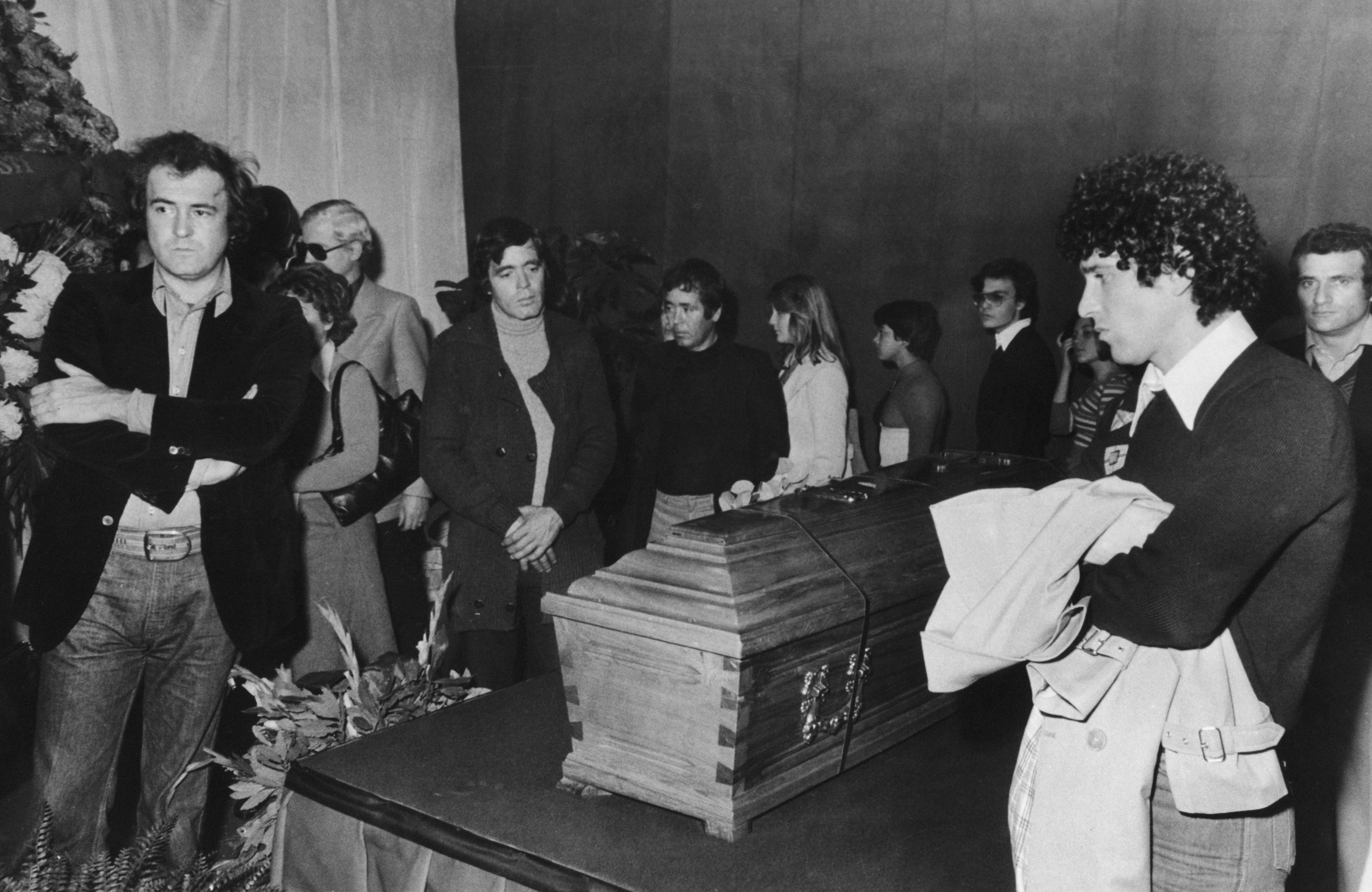

A great gash on Pasolini’s head had matted his hair with blood. One of his ears was nearly severed off. He had battered fingers, a fractured arm and ribs, and a vicious kick or two to his groin had crushed his testicles and burst blood vessels causing internal bleeding in his lower abdomen. And then for good measure he had been driven over by his own car one or two times (that was never resolved) literally bursting his heart. He was wearing his vest because he’d taken off his shirt to staunch the blood from his head wound before making a final desperate 70m sprint and collapsing. The shirt was found some way from where the body lay.

The police investigation was a farce. By the time forensic scientists turned up so many people and cars had driven there, parked and trampled over the crime scene, including a group of boys who played football a few metres from the corpse, it was impossible to say for certain what had happened. Pelosi had been stopped by traffic police at around am speeding in Pasolini’s car down the wrong side of the road. It took a while for two and two to be married together and then he was put on trial for murder.

The judge at the initial hearing concluded that Pasolini had been killed by Pelosi and “others not known”. This latter part of the verdict was redacted by an appeal court, pinning the blame solely on the youth whose confession had contained a key “gay-panic” defence. Pasolini, according to Pelosi, had tried to force him into anal sex, becoming violent when he refused. Pelosi had only been defending himself. That version of events suited the government, the police, the right-wing press and fascists, everyone in fact who had an interest in seeing Pasolini dead and damned.

No one who knew Pasolini, even his enemies, had ever witnessed him being violent. He was essentially a gentle man who would not have attacked a hustler because he didn’t want to do what he wanted him to do. He loathed violence, even in self-defence, once apologising to a young fascist thug for pushing him away when the other attacked him.

It’s highly unlikely Pelosi could have done the sort of damage Pasolini suffered on his own, particularly if his victim was struggling with him. It’s impossible he could have done so and come out of it without a scratch and with no blood on his clothes. It’s improbable he could have driven the car over Pasolini’s body several times without knowing it. It’s highly suspicious a ring which fitted tightly around Pelosi’s finger could have come off in the struggle to be conveniently found a little way from the body by the police.

Was Pelosi set up to take the blame? He was 17. He’d be sent to a juvenile prison to do a not particularly long prison term. Much later, in 2004, he went on national television to retract everything. He’d gone willingly with Pasolini. He’d got out of the car to take a piss and had been jumped on by another man with a ‘southern accent’. He’d heard Pasolini’s cries of help while at least two other men beat him to death, ran over his body and partially set it alight – that latter piece of evidence was included in the original autopsy report but seems to have been forgotten or ignored in the final official account.

The murder had always seemed like an assassination to Pasolini’s friends. But the opportunity for his critics and enemies to use his own death to condemn the man was too tempting. There have been calls to have the case reopened. Evidence that a print of Salò had been stolen shortly before the murder and that Pasolini may have gone to Ostia to meet the extortionists has been mooted. At an even later stage Pelosi seemed to corroborate this, confessing that he’d known Pasolini for several months. Others saw his murder as the result of a sort of death wish. Some pointed to the horror depicted in Salò as symptomatic of Pasolini’s disturbed state of mind, forgetting that a film is just that, not someone’s life. Others still saw the hand of the mafia, perhaps doing the dirty work of “men on the right”.

It was a dangerous time in Italy, after all. A little after Pasolini’s death, right-wing terrorists would leave a bomb in Bologna station, killing 85 and wounding over 200. In 1978 former Prime Minister Aldo Moro was kidnapped and then murdered in circumstances that have never been clarified. It’s not at all far-fetched that a critic of the right, a thorn in the side of so many vested interests, a great filmmaker who could excite the movie-going public with sometimes thinly disguised Marxist propaganda, a great writer who was deeply immersed in a novel about the byzantine and ruthless machinations of the oil industry, was murdered by a group of hired thugs.

No one scenario makes absolute sense, and still, nearly 50 years later there is a reticence on the part of Italy’s rulers to seek the truth.

On the morning of 3 November, Pasolini’s niece Graziella Chiarcossi, who lived with him and his mother in Esposizione Universale Roma, had to tell Susanna that her son was dead, murdered that night on a beach in Ostia. When she had played the mother of Christ in Pasolini’s timeless Gospel According to Matthew, Pasolini had filmed her at the foot of the cross, her mouth open in grief with the terrible pain of loss registered on her gaunt face. That grief had been silent then. Now Susanna’s howls of anguish could be heard all the way down the street.

Around the 40th anniversary of Pasolini’s murder images – mostly murals – began to appear on walls around Rome. They showed Pasolini carrying his own body in a gesture that is clearly meant to trigger recognition: the Pietà, the moment, both contained in time and symbolic, when Christ’s body is placed for the last time in his mother’s lap. The artist, Ernest Pignon-Ernest, showed the lifeless Pasolini in the clothes in which he was found. So many groups have sought to make of Pasolini an icon – a martyr, I suppose – of the left, of his sexuality, of his belief in freedom of expression, of the total artist, taking the analogy a little further by depicting him as the original Icon is only a new riff on what he would have called contamination: the conscious mixing of seemingly disparate things to create something new, the pollution of one purity with another, as when Pasolini set the grim realism of the world of Accattone to a fugue by Bach.

When he stepped forward into the light all those years ago, Pasolini would dazzle and be dazzled. But he would never stand still. Like his own version of Christ, he moved about through the world, constantly talking, constantly lecturing and, every now and then, stopping to touch and heal, an almost smile on his lips. And always with the knowledge that someone, somewhere would probably kill him. When an interviewer asked him if he found consolation in what he read in religious writings, he rejected the idea totally:

I’m not looking for consolation. Like any human being, every now and then I look for some small delight or satisfaction. But consolation is always rhetorical, insincere, unreal... What use is consolation? “Consolation” is a word like “hope”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments