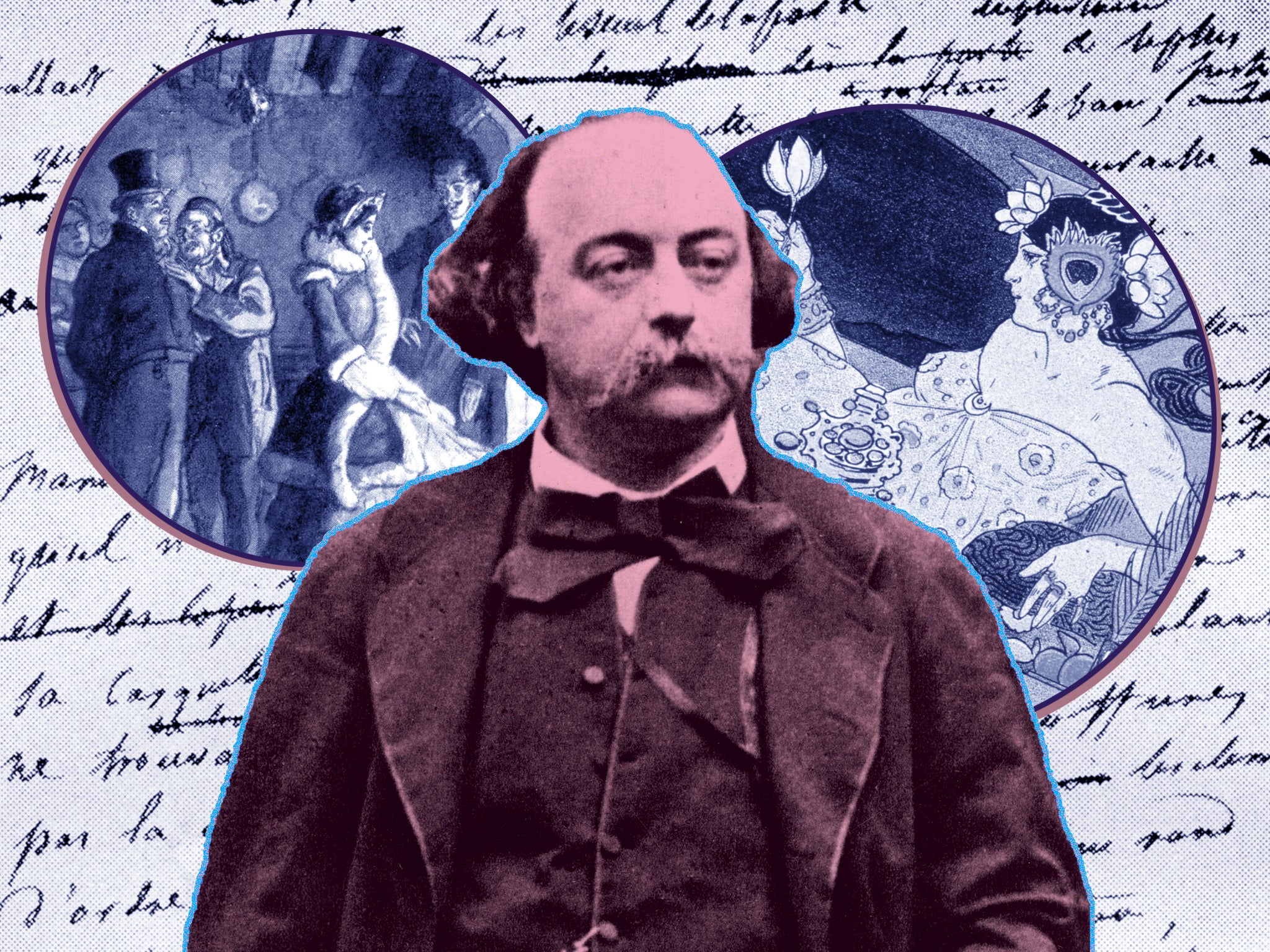

‘Literature! That old tart!’ How Flaubert became the father of the modern novel

There is the time before Flaubert and the time after him. Using style over subject and incorporating realism and symbolism, he changed prose writing for ever. Kevin Childs on the genius behind Madame Bovary

The wind is warm as it rustles the great bank of yellow reeds on the riverside. They susurrate, whispering to each other, nodding and weaving their delicate heads together like lovers. The breeze brings with it the dark scent of black earth, rotting vegetation, sharp-smelling manure and, above this, as if from some distant place, a clean dry smell of sand. The desert lies just beyond a band of brilliant green that bounds each side of the river, dry stony mountains and endless sand dunes the only threat of a world beyond this narrow paradise.

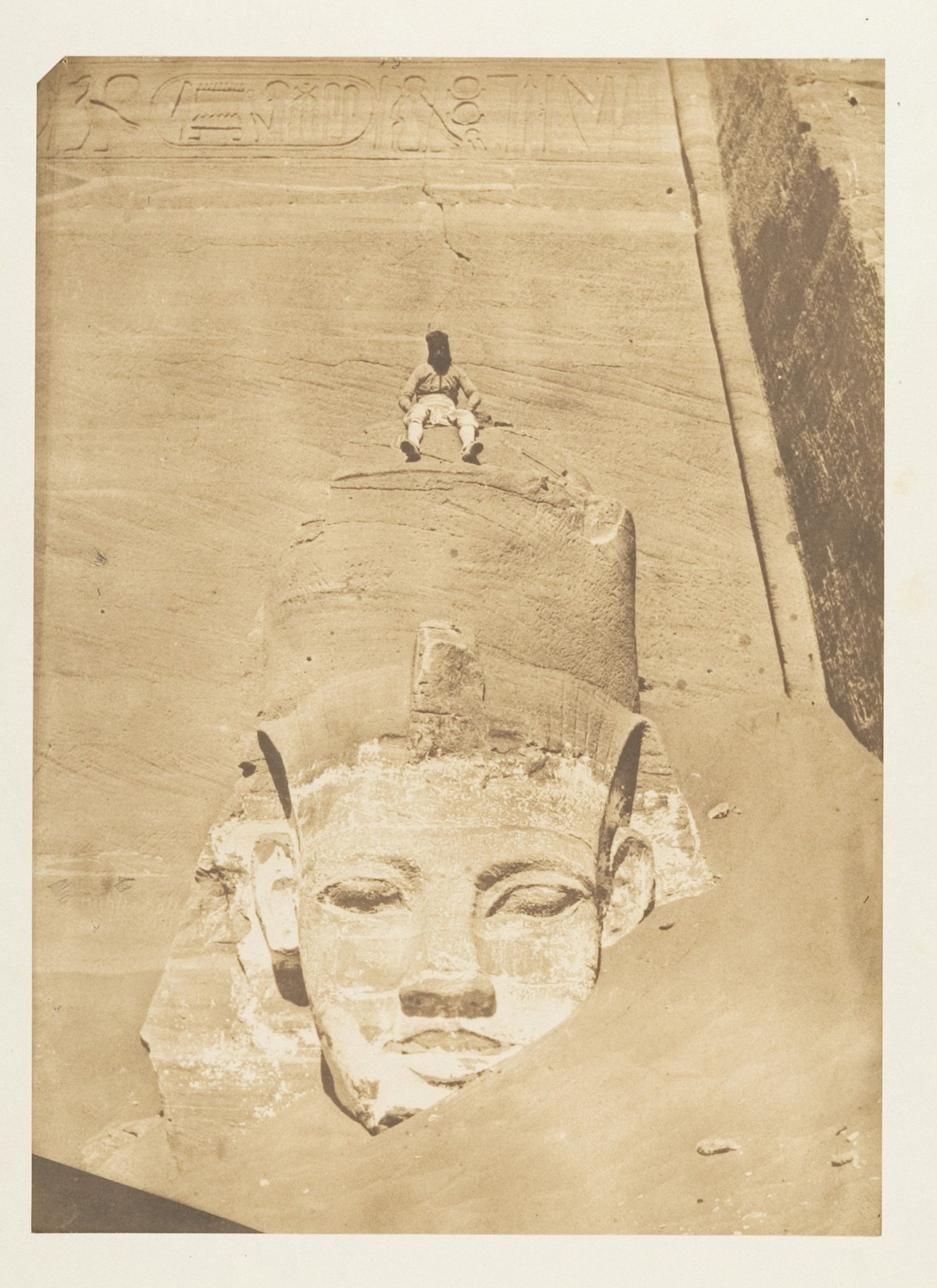

A felucca, its great white intersecting sails bloated with wind, glides gently through the blue water, heeling, its keel cutting the river in two. The captain sits cross-legged in the bow. Under a canvas awning its two passengers, Frenchmen – all sunburned and turned native in wide Turkish trousers and long white cotton chemises, cotton bands wrapped about their shaved heads, puffing on shishas – are taking it all in.

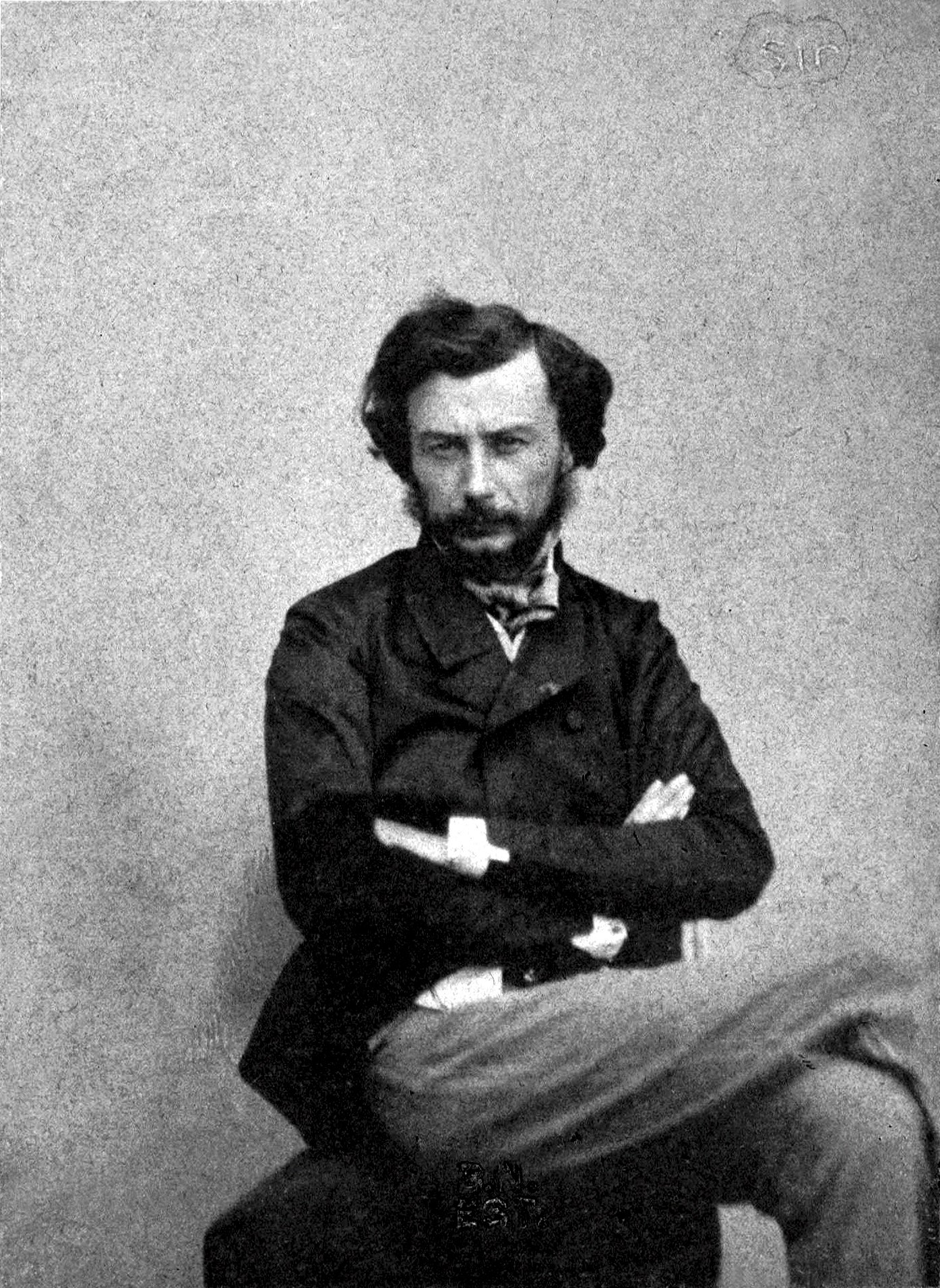

Gustave Flaubert and Maxime du Camp think very highly of themselves, like most young men. They’re on an adventure of a life time: a long, long trip up the River Nile to the borders of Upper Egypt, taking photographs of the monuments they see, writing notes and detailed, beautiful letters back home, watching, eyes beady in the firelight, lithe young men dance to the music of flutes and drums, and, whenever the opportunity allows, passing under the low painted wooden door frames of brothels, within, the women in loose, colourful gowns, their flashing eyes elongated with antimony and everywhere the sharp scent of sandalwood.

A journey through time itself.

Flaubert was restless. He was chafing at a recent setback, his friends’ rather merciless criticism of a novel he’d just finished about the strange anchorite Saint Anthony and the temptations which had assailed him in the deserts just to the west of where they sailed. He thought about it a lot. Now that he’d seen the places he’d described in his imagination, he recognised the folly of trying. He’d return to the story, but it would be a very different thing by then.

In the meantime, the words of his closest friend and most honest critic, Louis Bouilhet, kept rattling about his head in quiet moments. Write about now, write about what you know, the places you’ve lived, the good, dull bourgeois people who are your neighbours. To prove him wrong, he’d set off for the most remote and strange place he could think of, accepting Du Camp’s invitation to travel to Egypt and then on through the Levant to Constantinople.

He was young, his father had left him well off, he had the time needed for such adventures in those days. And during that lengthy trip of nearly two years, everything he would do, everything he would write would be incubated. The first great modern novel, the first steps towards modernism itself, towards Joyce and Woolf, Proust and DH Lawrence, the triumph of style over the Romantic obsession with plot and passion. As he wrote to Bouilhet when he returned to Cairo from his trip upriver:

Literature! That old tart! We’ll need to dose her with mercury and pills and clean her out from top to bottom, she’s been so badly screwed by filthy pricks!

And travelling so far from friends and family he was homesick too for the ordinary, everyday life of Normandy, as he wrote in his travel notes:

Far away, on a river milder and less ancient that this, I know a white house whose shutters are closed now that that I’m not there. The poplars, bare of leaves, are trembling in the cold mist, and cakes of ice are drifting on the river and lolling against the frozen banks. The cows are in their shed, the espaliers are covered with straw, and from the farmhouse chimney smoke rises slowly into the grey sky.

It was early in 1850. Back in France the electorate had voted Louis Napoleon – the nephew of the great Emperor, Bonaparte – to become president of the Second Republic, and he was already plotting the coup that would make his position permanent, just as his uncle had done 50 years before. It had been less than two years since Paris erupted into violent revolution, yet again, overthrowing the “People’s King” Louis Philippe, and demanding a greater say in the government, a broadening of the franchise, freedom of the press and bread for all. Louis Napoleon had seen his chance, slipping back into the country from exile, just as the Orleanists slunk off to west London to live out their days in comfortable frustration.

Here was the man who had always made my heart beat faster than any other writer, and whom I perhaps loved better than anyone I didn’t know personally

Early on 24 February 1848, Flaubert, Bouilhet and Du Camp had set out from the Place de la Madeleine in Paris in search of information, coffee and just to be part of history, in no particular order. Crowds had gathered, angry at a massacre of working-class protesters by the National Guard the previous evening. The atmosphere was tense, the people’s blood was up.

At one street corner, they encountered a woman, stripped to the waist, her breasts like half-moons in the first light, brandishing a knife in some odd parody of Eugene Delacroix’s famous painting of Liberty Leading the People. She was urging anyone who’d listen to storm the Tuileries Palace and depose the king. In the mass of people, the three friends lost each other. At the Tuileries, from which the royal family had already fled, mobs of people rampaged through the gilded rooms. The Palais Royal, Louis-Philippe’s old ducal residence, was already being ransacked when Du Camp and Flaubert, who’d found each other again in the streets outside, witnessed furniture, books, mirrors, valuable paintings being hurled into great bonfires in the palace garden.

Later Flaubert would remember these scenes when he came to write Sentimental Education and its hero, Frederic Moreau’s vaguely detached observation of the revolution of 1848:

Although [he] was no warrior, he felt his Gallic blood leap. The zeal of the enthusiastic crowds mesmerised him. Sensuously, he breathed in the stormy air, full of the smell of gunpowder. And at the same time, he trembled in the throes of a vast love, a love that was supreme and universal, like the heart of the whole of humanity beating in his breast.

Gustave Flaubert was born 200 years ago in December 1821, a few months after that other great French writer of the mid-19th century, Charles Baudelaire. His father, Achille-Cleophas Flaubert, was the head of the most important hospital outside of Paris, the Hotel Dieu in Rouen. His mother, Caroline, who fretted too much but adored her younger son, suffered all her life from debilitating migraines which kept her supine for many hours in darkened rooms. She would also be one of his most astute critics.

Hating school, he loved the family holidays on the Normandy coast at Trouville where he would first fall in love at the age of 14. He hated even more the rigour of studying law in Paris, eventually abandoning it with little regret not so much because of his failure to pass exams, but because of the first manifestation of epilepsy, which would follow him all his life. It was decided his health was too delicate for the law.

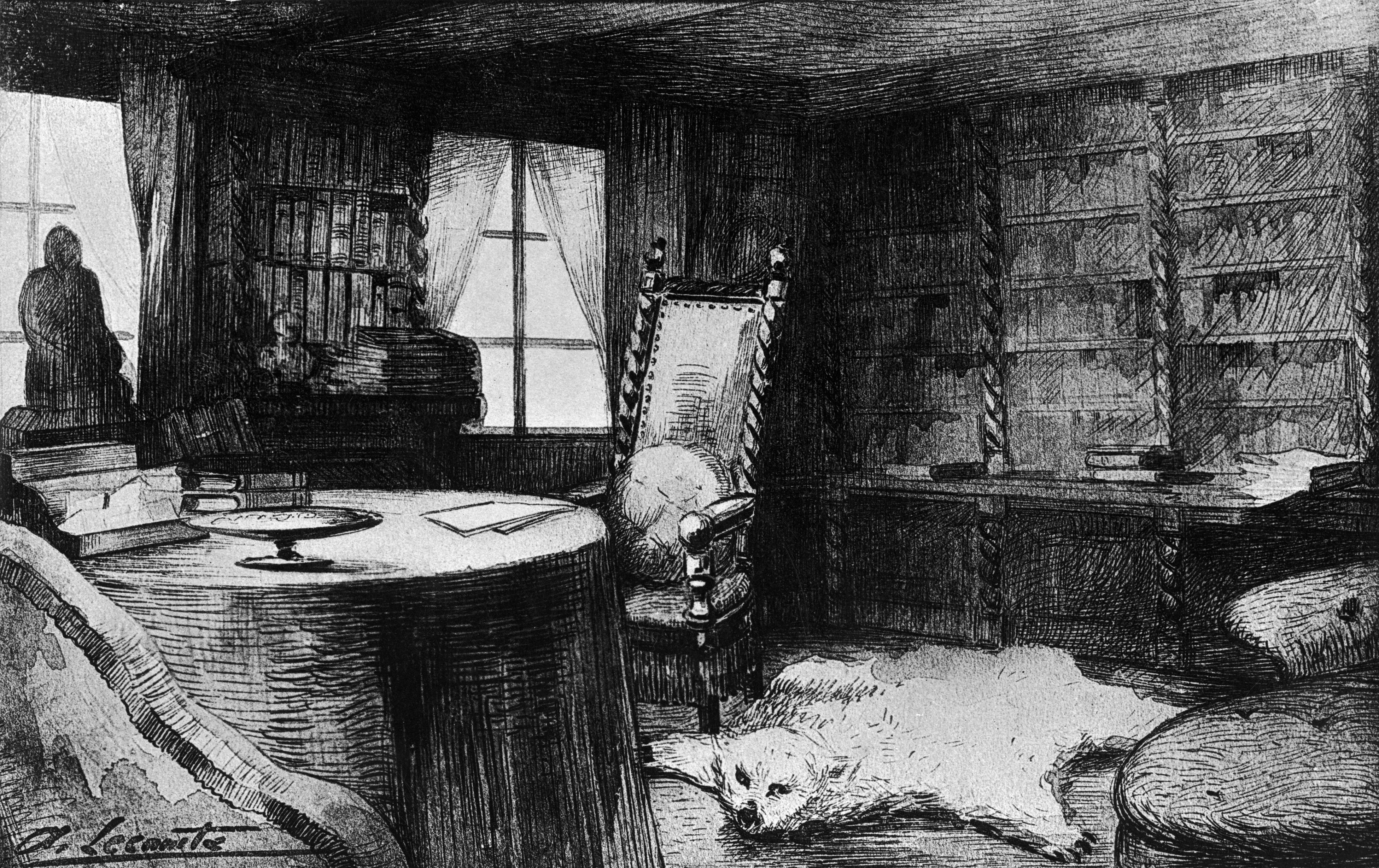

In the meantime, Achille-Cleophas had moved his family from the flat they’d inhabited in the Hotel Dieu to a pretty villa-cum-farmhouse in the small hamlet of Croisset, a short ride from Rouen on the banks of the River Seine. This was the “white house whose shutters are closed” he wrote about in his Egyptian journal. Croisset would become his bolthole, his place of refuge from the world, where he would write all his great novels, Madame Bovary, Salammbo, Sentimental Education and, yes, that final, febrile version of The Temptation of Saint Anthony. He would love it all his life and very nearly lose it when financial mismanagement left him virtually broke at the end.

But before all that, tragedy struck the Flaubert household twice in the space of a few months. Achille-Cleophas died of septicaemia in January 1846, followed by his daughter, Gustave’s beloved sister, Caroline, in March, the victim of puerperal fever after giving birth to a daughter, also called Caroline. “[M]y eyes are as dry as marble,” Flaubert wrote to Du Camp. “It’s odd, but as expansive, fluid, abundant and overflowing as I feel where fictional sorrows are concerned, to that same extent do the real ones sit in my heart bitter and flinty; the minute they enter it, they harden.”

That fictional life, the life of a writer who has only thoughts and ideas and dreams of the characters who inhabit his inner world would soon engross him. He would be lured into the literary and artistic world of Paris where, even before he’d published anything significant, his talent was recognised. While still a law student in 1842, Flaubert would join luminaries at dinners and lunches held by the impresario Maurice Schlesinger, whose wife, Elisa, had become the object of his teenage heart when he rescued her shawl from the sea at Trouville one summer. Here were Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt, Alexandre Dumas and Hector Berlioz, the German poet Heinrich Heine, the critic Charles Sainte-Beuve. At another salon, held by the fashionable sculptor James Pradier at his studio behind the church of Saint Germain-des-Pres, he met Victor Hugo, the most famous writer in France at the time. He was impressed, as he wrote to his sister:

Here was the man who had always made my heart beat faster than any other writer, and whom I perhaps loved better than anyone I didn’t know personally. The conversation was about torture, vengeance, thieves, etc. It was I and the great man who chatted the most; I can’t remember whether what I said was intelligent or rubbish. But I said a lot.

If Flaubert had written nothing other than ‘Madame Bovary’, his name would still be known. It is, quite possibly, the greatest novel of the 19th century

It was at Pradier’s atelier he encountered the sculptor’s sometime muse Louise Colet. A party in 1846 celebrating the 16th anniversary of the July Revolution was the occasion. She wore blue, her fashionably long ringlets brushed her bare shoulders. The would-be writer and the not-quite-celebrated poet, 11 years older than he, locked eyes across the plaster casts and half-completed busts – one of which was of Flaubert’s own father – then fell into bed with each other. It wasn’t a happy prelude to a very unhappy relationship. Flaubert failed to perform.

I’m a poor excuse for a lover, aren’t I?... Do you know that what happened had never happened to me before? (I was dog tired and as taut as a cello string.) Had I been a man proud of his person, I would have been terribly upset. I was indeed upset, but on your account.

He was able to rectify the situation the following evening during a cab ride through the Bois de Boulogne. “For a split second,” he wrote to her, “I stood at the edge and saw the dizzying abyss, then pitched forward.” Falling in love, it seems, was dangerously reminiscent of an epileptic fit. It was also something he could do with ease. He would never marry, but he would remember the women he had loved, like broken cobbles on a street washed with rain: Louise Colet, Pradier’s own estranged wife (another Louise), and his niece’s former English governess, Juliet Herbert.

It was, perhaps, with this in mind that he wrote to Louis Bouilhet nearly four years later during his trip up the Nile of a night he spent with a celebrated dancer in Esna. Kuchuk Hanem is everything that Louise Colet is not, and the transactional nature of their encounter is countered by real tenderness on the part of young Flaubert, which belies any charges of mere orientalism, and a sort of innocent naiveté on the part of the famous courtesan:

When it was time to leave, I didn’t… I covered her with my jacket, and she fell asleep with her fingers in mine. As for me, I hardly shut my eyes. Gazing on that beautiful creature asleep (she snored, her head rested against my arm: I had hooked one finger under her necklace), my night was one long, infinitely intense reverie – that was why I didn’t go. I thought of my nights in Paris, at the brothels – droves of old memories came back – and I thought of her, of her dance, of her voice as she sang songs that had little meaning for me, in which I couldn’t even distinguish words. That went on all night. At three o’clock I got up to piss in the street – the stars were shining. The sky was clear and so very far away… As for the sex, it was good – the third time was especially ferocious, and the last tender – we told each other many sweet things – towards the end when we embraced it felt sad and loving.

All these women, and not a small part of his own psyche, would merge into the single most memorable and intensely feeling character he would write. If Flaubert had written nothing other than Madame Bovary, his name would still be known. It is, quite possibly, the greatest novel of the 19th century, because, simply, it so real, so urgent, so now. Everyone recognises something of themselves in Emma Bovary, whether we like it or not.

According to the account given by Maxime du Camp, it was during an evening by the Nile’s second cataract, watching the river “dash itself against the sharp, black granite rocks” that the thought, or at least the name of the title character came to Flaubert as if in a flash. Much has been written about this slightly improbable account. What story was Flaubert actually thinking of? Bouilhet had urged him to write something contemporary, but the tale on which Madame Bovary is said to have been based couldn’t have been known to the writer until his return to France. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t have some notion of a woman he wanted to write about and that the name, so strong, so rounded in the mouth, so earthy, didn’t come to him while watching the foaming waters of the Nile. That trip, after all, would influence the rest of his life and much of what he wrote afterwards.

The story of a beautiful country girl and her lack-lustre, luckless country doctor husband may have been borrowed from one or two real-life narratives, but it becomes a story about everything – ambition, disappointment, love and its opposite, greed and ruin, betrayal and tragedy. There’s humour, often brutal, the language is beautiful and sometimes beautifully ugly, the realism shocking, and, in a pattern Flaubert would repeat throughout his career, the novel took him several years to write. He sweated blood over it.

It still pulls no punches. In the scene in which Emma falls for the faithless Rodolphe – who will use her and dump her when she had need of him most – his main weapon of conquest is truth. He explains his bad reputation as a need to constantly distract himself. Emma replies, wistfully,

“We don’t have such distraction, we poor women!”

“Sad distractions they are, for they don’t bring happiness.”

“But can one ever find that?” she asked.

“Yes, one day you encounter it,” he answered…

“One day you encounter it,” Rodolphe repeated, “one day, all at once, just when you were despairing. All at once horizons are revealed, it’s like a voice crying out: ‘There it is!’ You feel the need to make of that person the confidant of your life, to give him everything, to sacrifice everything to him! Nothing’s explained, everything is divined. You have seen each other in your dreams.”

(And he looked at her.)

Emma’s behaviour is presented as a direct consequence of the suppression of women by a patriarchal society that expects madonnas but desires whores

“At last, it is there, this treasure you have looked so long for, there in front of you, shining, sparkling. But there’s still a doubt, you dare not believe it. You’re dazzled, like someone emerging from darkness into light.”

And as he spoke Rodolphe pantomimed his words. He drew his hand across his face like a man who is feeling dizzy; and then he let it drop on Emma’s.

The cynicism of it all is underscored by the tedious speech of some local bigwig which they’re supposed to be listening to and which interrupts every now and then Rodolphe’s seductive flow. When they ride together at her too trusting husband’s suggestion – “Certainly! Excellent! Just the thing!” – the world around them seems to conspire, the dampness of the red earth, the yellowing October leaves and soft green turf under foot, the great stout trunks of a pine forest, everything speaks of a quickening of the pulse. Flaubert shows us virtually nothing of the sex we know is happening, but the sensuality of the language does it all. Back in Egypt, while making notes on his voyage he’d described in detail a handsome youth who had rowed him and Du Camp from the felucca to some site along the bank. Returning, the moon is up and his imagination fixes on odd details that instantly fetishise the boat, the night, the boy with his silver earring and strong arms:

We are rocked by wind and waves; night falls; the waves slap the bow of our dinghy, and it pitches, the moon rises. In the position in which I was sitting, it was shining on my right leg and the portion of my white sock that was between my trouser and my shoe.

The detail of the white sock stands in for a whole universe of desires, and it’s a literary or stylistic trick which he uses to great effect whenever he wants to suggest something beyond the mere everyday observation in Madame Bovary. In an otherwise realist novel, it’s an early taste of symbolism in which objects and landscapes take on wider meaning.

After struggles with nervous editors who wanted the author to snip away at some of the more explicit and politically shifty passages – including the whole of the scene quoted above – Madame Bovary was published serially in Maxime du Camp’s Revue de Paris in late 1856. Even an expurgated version, which came with a disavowal by the author of the omissions, fell foul of the Imperial censor, and in January 1857 Flaubert, the Revue and its printer were charged with “an affront to decent comportment and religious morality”.

Back on their felucca as they glided down the Nile, Flaubert and Du Camp had argued about what the second half of the century would bring. Flaubert saw a world dominated by the school master and his cane:

For me it is almost certain that at some more or less distant time [society] will be regulated like a college. Teachers will be the law. We’ll all be wearing uniforms. Humanity will no longer commit barbarisms as it writes its insipid theme, but – what wretched style! What lack of form, of rhythm, of spirit!

That schoolmaster was in charge now, in the person of a portly, middle-aged emperor who thought he could somehow pull the wool over the eyes of France if he were more bourgeois than the bourgeois. Art and good style, the novel as a reflection of the world, the trajectory of Emma Bovary’s tragedy meant nothing to men like Napoleon III. He had none of his uncle’s aesthetic sense and all of his censorial political instincts.

Ultimately, the attempt to censor Madame Bovary and convict its author failed. What rattled the authorities wasn’t the adultery in the book, but the book’s determination, or rather its authorial voice’s determination not to condemn that adultery. Emma’s behaviour is presented as a direct consequence of the suppression of women by a patriarchal society that expects madonnas but desires whores. Anything in between doesn’t exist. For that matter, the absence of a moralising authorial voice sometimes implies approval of her behaviour. When Leon, another of Emma’s lovers, awaits their first tryst in the Cathedral of Rouen, it seems that even the ecclesiastical architecture connives in their lovemaking:

The church like a huge boudoir spread around her; the arches bent down to gather in the shade the confession of her love; the windows shone resplendent to illumine her face, and the censers would burn that she might appear like an angel amid the fumes of the sweet-smelling odours.

Her lack of maternal instinct, her contempt for her husband and her sexual abandon – the scene in the cathedral is followed by a day-long cab ride around the town during which it is clear that Emma and Leon are engaged in sexual intercourse – are presented as natural, while her death and the circumstances surrounding it, rather than being just deserts, are merely the direct result of all the shabby usage by the shabby men who might otherwise be that conduit of moral condemnation demanded by the government.

Flaubert’s counsel turned the censors’ argument on its head. It was society, and particularly the rancid religious upbringing of young girls that produced women like Emma Bovary, and the novel makes this plain. The argument, specious though it sounds, worked and Madame Bovary was acquitted. This allowed it to appear, later in 1857 in a single-volume unexpurgated edition. The trial, and the notoriety it garnered made Bovary an instant hit. Hugo wrote to Flaubert: “You have produced a beautiful book, sir, and I am pleased to tell you so… Madame Bovary is a real work.” Baudelaire wrote a glowing review, highlighting the absurdity of the censors’ objections. Women everywhere began to identify with Emma Bovary and wanted to make this known to its author. One of these was the novelist George Sand, who would become a close friend as Flaubert entered middle age.

What strikes me as beautiful, what I would like to create is a book about nothing, a book without external attachments held aloft by the internal force of its style, as the earth stays aloft on its own, a book that would have almost no subject or at least in which the subject would, if possible, evaporate.

As Flaubert was being lionised by Parisian literary society, so there was an expectation of a second novel, another great piece of realism, of naturalist fiction, which the young Turks, men like Emile Zola, and the writer’s friends expected of him. Flaubert had no intention of being pigeon-holed. Instead, he began work on a novel of historical fiction, returning once again to the exotic scents and scenes of North Africa and a world that couldn’t be further from his own.

It would be a book in which style counted more than subject, a book which, despite all the events, all the episodes, the passions and reversals, nothing really happens, nothing edifying, that is. Salammbo is set in the ancient city of Carthage during the late third century BC. Its central character, the eponymous heroine, is the daughter of the Carthaginian general Hamilcar during a time of great peril for the city when her mercenary armies rebelled against her. Men desire Salammbo just as her body, her clothes, her bearing are a sort of sensual reverie and just as she is dedicated to a form of religious abstinence in the service of the goddess Tanit. Throughout, they can look but not touch.

There is blood, copious amounts of it, violence, torture and barbarism. There are jewels and moonlit nights on the Gulf of Tunis, terrifying gods and perfume-drenched human sacrifices – at times it feels like some long, long sado-masochistic orgy in which the reader is the master of ceremonies – everything, in short, that the writers of the Decadent movement later in the century would revel in. Having shown the way for Realism to grow with Madame Bovary, Flaubert seemed to be signalling to the Symbolist Movement his allegiance.

Or was he. From her glossy hair to her sandalled feet, Salammbo is enchained by gold, by precious gems, by priceless fabrics – like all young women, virgins, of Carthage she is supposed to wear a literal chain between her ankles wide enough to allow her to walk. She is encased in silver scales or enveloped in coloured silks. She is the ultimate object of the male gaze, cosseted, pressured, both captivating and captured, a moon, like the goddess she serves, who waxes and wanes, yes, but who, in the end, doesn’t do what is expected of her and dies as a result. She is a painting by Gustave Moreau:

From her ankles to her hips, she was enveloped in a network of tiny nacreous links that shone like fish scales. A blue zone girdled her waist, allowing her breasts to be seen through two crescent-shaped slashes, where carbuncle pendants hid the nipples. Her headdress was made of peacocks’ plumage, starred with jewels; a broad, flowing mantle, white as snow, fell behind her – her elbows were close against her body, her knees pressed together; circlets of diamonds were clasped on her arms; she sat perfectly upright in a hieratic position.

Unlike his coeval Baudelaire, he never really understood the life of the impoverished artist either. He lived in fashionable apartments, not rotten attics, and could always afford a good meal

The novel’s principal male protagonist, a leader of the mercenaries called Matho, alternates between blood-soaked battlefield heroics and thrashing about on the floor of his tent in impotent despair because he can’t possess Salammbo, and only when he is tortured to death in front of her does he achieve a sort of nirvanic catharsis.

Flaubert fretted about the writing of the book and dreaded its reception. It was so very different from Madame Bovary, a book that had no moral compass at all, not that he would have cared about that, and no real plot, a book that just was. The whole process made him ill. And yet, he couldn’t help himself.

When ‘Salammbo’ is read, I hope the author will not enter the reader’s thoughts! Few people will guess what sadness provoked the attempt to resuscitate Carthage, how I’ve lost myself in it out of disgust with modern life!

When it reached the hands of readers in 1862, after nearly five years of research and writing, the critics mauled it for all the reasons he expected, but the public loved it. Empress Eugenie asked her dress maker to produce a gown à la Salammbo for a costumed ball, only to have second thoughts when it became clear she’d be wearing little more than jewels threaded with gold. The composer Berlioz couldn’t put it down, and George Sand compared it favourably with Dante, wanting to get to know the author better.

Back in Egypt 10 years before, Flaubert had expressed a certain amount of distaste for the giant vestiges ancient culture, with the exception of Luxor and Karnak, likening them to the already stalely romantic views of Medieval churches and Pyrenean waterfalls. He’d questioned the whole expectancy of such things:

Oh necessity! To do what you are supposed to do; to be always, according to the circumstances (and despite the aversion of the moment), what a young man, or a tourist, or an artist, or a son, or a citizen, etc. is supposed to be!

Yet his recreation of ancient Carthage is mesmerising, vibrant, wild even, and archaeological. The clash of symbols, the great colonnades and circular harbour, the charge of elephants and the still, baking heat of a desert valley all impressed one young reader. “My son, Guy,” wrote Laure du Maupassant, an old family friend, “upon hearing your descriptions, which are sometimes so elegant and sometimes hair-raising, his dark eyes flash, and I believe that the noise of battle and the trumpeting of elephants resound in his ears.”

“The most beautiful works are those that have the least matter,” wrote Flaubert as a sort of manifesto of what would become art for art’s sake. “The closer expression hugs thought, the more words cleave to it and disappear, the more beautiful it is. Therein lies the future of art. As it grows, it grows more ethereal, from Egyptian pylons to Gothic windows, from Hindu poems twenty thousand lines long to Byron’s ejaculations.”

When he came back from his travels in the Near East, Flaubert had grown an extravagant moustache and a greater girth. He would no longer be the lithe, slim young man women like Louise Colet and Madame Pradier had tilted their ringlets at. That’s not to say that women didn’t still find him altogether fascinating. He seemed to understand them and to sympathise with their situation. Or so they thought. A bourgeois through and through, at least in upbringing, he nevertheless despised the bourgeoisie. Unlike his coeval Baudelaire, he never really understood the life of the impoverished artist either. He lived in fashionable apartments not rotten attics and could always afford a good meal at a good restaurant, even when his money began to dry up towards the end. It gave him the leisure to dip his pen into the limpid pools of style, to spend 10 years, or near as damn it, writing a novel.

But as he grew older, ill health began to stalk him and the processes of writing became more and more difficult. That youthful sojourn in the Levant had left him with syphilis, then an incurable disease the symptoms of which could only be alleviated by treatments almost as atrocious. But it wasn’t so much that he was tired and sick as that he had done it all in his first two novels. Sentimental Education, as near to a roman à clef as he would get, is a sort of repetition of Madame Bovary with a listless and unhappy hero rather than heroine whose lack of real ambition leads to, well, a lack of ambition and a dull middle age.

The final version of The Temptation of Saint Anthony is, if anything, an even more esoteric evocation of the remote past than Salammbo, nearly drowning in long digressions on theology and philology. As well as the usual temptations of the flesh, Anthony watches while all the dogmas and religious systems thought up by human brains are paraded before him in an almost endless stream of theosophical drivel. Each is found wanting. As Flaubert wrote to a friend at the time of The Temptations’s publication:

Searching for the best religion or the best form of government strikes me as idiocy. It seems to me the best one is the one that’s moribund, because in dying it makes way for another... It’s because I believe in the constant evolution of humanity and its unceasing forms that I hate all the frames into which people want to cram it.

Anthony’s revulsion at so much cant and intellectual masturbation leaves him open to the inevitable temptations of sensuality, and a parade of winsome goddesses eventually forces him to cry out “I feel the desire to lie flat upon the earth that I might feel her against my heart; and my life would be imbued with her eternal youth!”

For him, experience remained the only religion worth muttering a prayer to and the sensual world the only temple worth preserving

Physical experiences had always excited Flaubert, more so than purely intellectual ones. Even in middle age he was still the sensual young man who wrote to his friend Louis Bouilhet from Cairo that his desire to experience pleasure was all encompassing, including the sort of pleasure the young male masseurs in the local baths offered:

Here it is quite accepted. One admits one’s sodomy… sometimes you do a bit of denying, and then everybody teases you and you end up confessing. Travelling as we are for educational purposes, and charged with a mission by the government, we have considered it our duty to indulge in this form of ejaculation. So far, the occasion has not presented itself. We continue to seek it, however.

Later he would let Bouilhet know of his success. Jean Paul Sartre rejected these passages in Flaubert’s letters and journals as inauthentic, which says rather more about his homophobia than Flaubert’s Catholic sexuality. There’s no particular reason to follow his reasoning. Flaubert was writing to an intimate friend whose own sexuality may have been fluid – he calls Bouilhet “my dear old bardash” at one point, using the Arabic word for what we would call a gay man. He was experiencing someone else’s life, vicariously perhaps, experimenting as so many white western Europeans did in North Africa and the near east, but there’s no judgement in this.

Ultimately, for Flaubert, life is a series of sensual encounters which have as little or as much meaning as we choose to give them. It was what Rodolphe was trying to tell Emma Bovary, what Salammbo craved and what would drive Saint Anthony mad. But in the world which Flaubert inhabited, the world of 19th-century Bourgeois France, only men had the potential to live such a life. Women, for the most part, were constrained and when they chose to break those constraints, were punished for it.

Among his last works, not counting the unfinished Bouvard et Pecuchet, three short stories, published together as Trois Contes, sum up these litanies of experience: a simple peasant girl whose saintly dying goes almost entirely unnoticed other than by her pet parrot which is transmogrified into the Holy Ghost in her mind as it flies about her deathbed; a voracious medieval hunter who learns humility through a series of terrible reverses; and Herodias, the mother of Salome, who uses her daughter to silence the religious intemperance of John the Baptist. If the first two have a defined moral voice, the last is a return to Flaubert’s sensual supremacism. The body of a beautiful dancing girl, channelling all those lovely women he’d encountered in Egypt and the Near East, silences the pious words of a disembodied saint.

Again the dancer paused; then, like a flash, she threw herself upon the palms of her hands, while her feet rose straight up into the air. In this bizarre pose she moved about upon the floor like a gigantic scarab; then stood motionless.

The silken veils of pale hues that enveloped her limbs when she stood erect, now fell to her shoulders and surrounded her face like a rainbow. Her lips were tinted a deep crimson, her arched eyebrows were black as jet, her glowing eyes had an almost terrible radiance; and the tiny drops of perspiration on her forehead looked like dew upon white marble.

And all this, the implication being, is hidden by her veils while her naked body is revealed. Really, John had no chance.

The watershed moment for both France and Flaubert came in 1871. Notwithstanding the defeat and abdication of Napoleon III following France’s humiliation during the Franco-Prussian War, and the hideous violence with which the Paris Commune was crushed by an interim government, Flaubert looked back at the years before the war with nostalgia.

“We are all of us emigres left over from another age”, he wrote. And soon his old friends began to die. His beloved mother, Caroline, in 1872 and before that – before the war even – Charles Baudelaire had given up the struggle against alcoholism and venereal disease, and Louis Bouilhet, his closest friend, had died of kidney disease at the age of 48, leaving Flaubert bereft. It was that death which, no doubt, gave the impression of a golden age gone by. Others would follow. Jules de Goncourt, whom he’d come to know and appreciate in the 1860s, succumbed to syphilitic dementia at only 39, George Sand and Louise Colet would die a few months apart. Though their relationship had grown bitter after the publication of Madame Bovary, and Louise had written some cruel things about him, her death gave him a moment of pausation, to reflect on all the years, writing a little later:

I’ve trampled over so many things, just to be able to go on living! In short, after an afternoon spent contemplating the past, I willed myself not to think about it any longer and returned to my work. Yet another end!

That was in 1876. Financial troubles, the mismanagement of family money by his niece’s husband now plagued him and, for the first time in his life, he faced real hardship, even the prospect of losing his beloved Normandy farmhouse. His past was catching up with him in other ways too. His health, never particularly robust in recent years, was at war with his appetite for rich food and wine and the syrup of mercury he’d imbibed to counter the effects of syphilis may also have provoked new epileptic episodes. Eventually his body gave out. On 8 May 1880, he got from his bed in the late morning as usual and was sitting on a sofa reading the morning papers when a sudden heart attack, or some say a brain haemorrhage, left him catatonic, clutching a bottle of smelling salts. By the time the doctor could come, he was dead. He was 58.

Emile Zola described his funeral in Rouen a few days later. Ever the realist, he couldn’t help sneering at the local bourgeoisie who probably associated the name Flaubert with the writer’s physician father and brother rather than the great French novelist. There was “not the least sign of bereavement on the faces of these onlookers, a city immersed in lucre”. The final indignity occurred when it became apparent that the grave dug for the coffin of a man over six feet tall was not long enough. Flaubert’s niece, Caroline, insisted that friends and family leave to allow the gravediggers to rectify the problem in private. And so, Gustave Flaubert, arguably the writer of one of the greatest novels in the French language, was left head down, feet towards the sky, not quite buried.

Three months later, Flaubert’s beloved Croisset was sold to industrialists who pulled it down to build a distillery. Nothing of substance remains.

In Madame Bovary and Salammbo, Flaubert had written the finest prototypes, if you like, of the two great strands of late 19th-century European literature, often at war, always in counterpoise with each other: realism, the stark and forensic examination of modern life, and symbolism, which endowed happenings and objects with poetic meaning beyond the mundane. He could be considered the high priest of both. He had also elevated humble prose to the palace of poetry, moulding, faceting, polishing and buffing his words into perfect sentences, sentences into paragraphs and paragraphs into chapters, until no one element could be cut away without ruining the whole. He had shown the way for later writers to use style as a metaphor, as a substitute even for plot. A book like Ulysses or Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is inconceivable without Flaubert’s great experiment in alienation in Madame Bovary. In this he could be seen as the father of the modernist novel.

And yet he would have despised all these labels. For him, experience remained the only religion worth muttering a prayer to and the sensual world the only temple worth preserving. It’s why he was so possessed by the exotic past, by the otherness of the East – he was thinking about his time in Egypt a few days before he died – and, yes, by the leaf mould in an October wood. Back in 1850, in Cairo, he’d written to Louis Bouilhet of his failed attempt at man-on-man sex. The young masseur he’d had his eye on in the local baths was not working the day he’d summoned up the courage to try. But he made the best of it all the same.

I was alone in the hot room, watching the daylight fade through the great circles of glass in the dome. Hot water was flowing everywhere; stretched out indolently I thought of a quantity of things as my pores tranquilly dilated. It is very voluptuous and sweetly melancholic to take a bath like that quite alone, lost in those dim rooms where the slightest noise resounds like a canon shot.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments