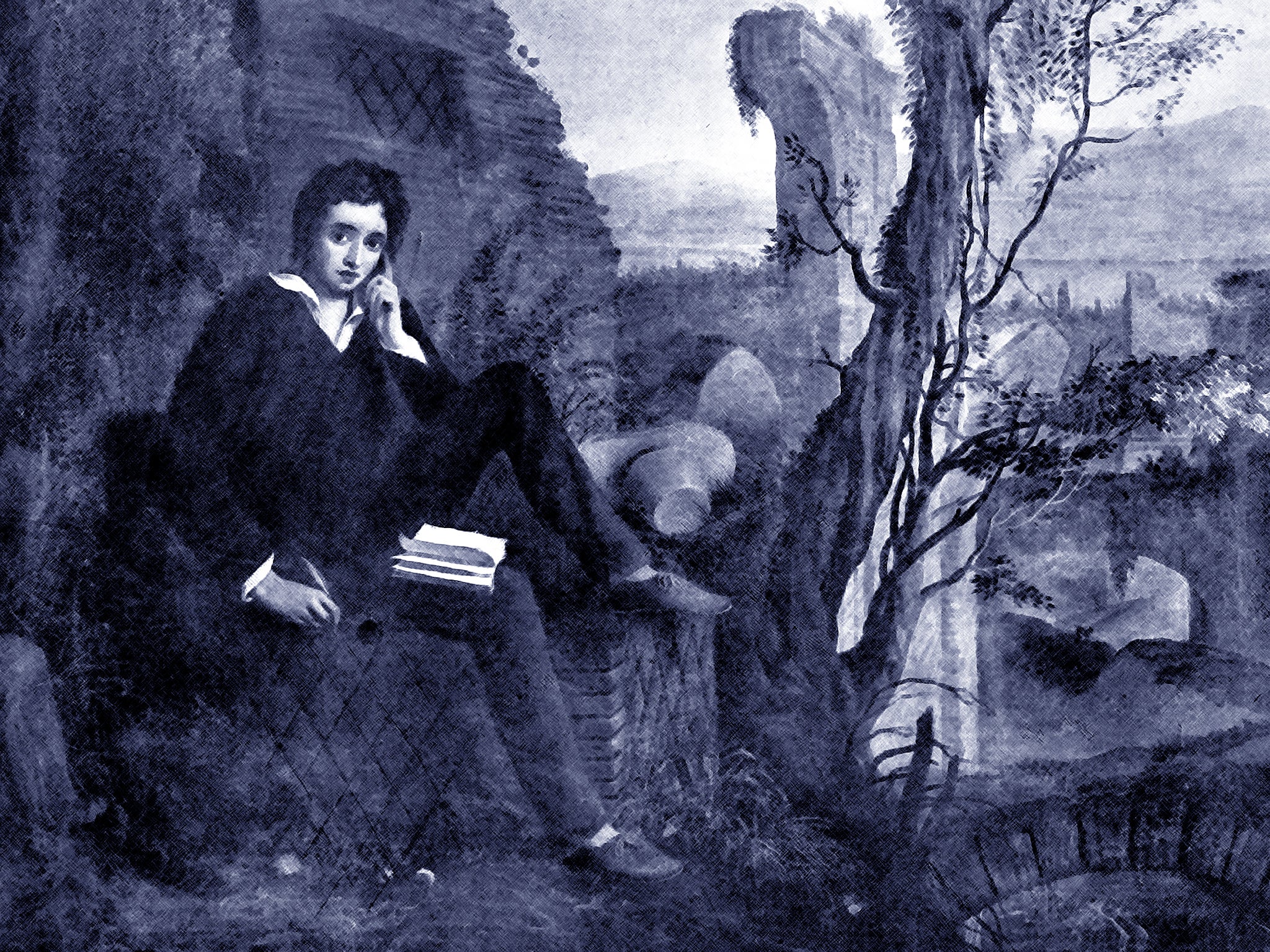

The tragic tale of Percy Bysshe Shelley – a poet whose words reverberate through the ages

Shelley knew the seductive power of lyric, the poignancy of the ballad, the exquisite charm of the love song, writes Kevin Childs

A light wind, slow at first, but gaining in strength, whipped up the flames that were spilling from the iron furnace on a beach just outside the seaside town of Viareggio, on the coast of Tuscany. Inside the furnace the body of the young poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, was gradually consumed by fire. Looking on were fellow poet Lord Byron and a friend, who also doubled as master of ceremonies, Edward Trelawny.

A handful of Tuscan militia and inquisitive fisherman made up the rest of the party. Shelley’s old friend, Leigh Hunt, remained in Byron’s carriage because he couldn’t stomach the spectacle. Trelawny had designed the portable furnace for the cremation, and now stood by the pyre, chanting Latin incantations and pouring libations of fragrant oil over the flames.

“I knew you were a pagan,” Byron commented to Trelawny, “not that you were a pagan priest. You do it very well.”

It was the 16 August 1822. More than a month earlier, Shelley, his friend Edward Williams and Charles Vivian had set off to sail across the Gulf of Spezia in Shelley’s little boat, the Don Juan, from Livorno to Lerici, where Shelley had been living with his wife, Mary, and infant son. Together with Byron, Hunt and Trelawny, in Byron’s house in Pisa they’d been discussing the creation of a new radical journal to showpiece their writings. There had been tensions between them in the burning July weather. Shelley and Williams were keen to return to their wives and had set off despite warnings of a coming storm.

One eyewitness who’d tried to rescue them gave an account to a friend, “The waves were running mountains high – a tremendous surf dashed over the boat which to his astonishment was still crowded with sail. ‘If you will not come onboard for God’s sake reef your sails or you are lost’ … one of the gentlemen (Williams it is believed) was seen to make an effort to lower the sails – his companion seized him by the arm as if in anger.”

Their boat capsized sometime around 6.30pm on 8 July, drowning all three onboard.

“You were all brutally mistaken about Shelley,” Byron wrote later to his publisher John Murray, “who was without exception the best and least selfish man I ever knew. I never knew one who was not a beast in comparison.”

Shelley’s reputation has suffered more than any of the great English Romantic poets. Always the least read of his contemporaries John Keats and Byron, he was, nevertheless, the finest lyric poet of the nineteenth century with a subtle understanding of rhythm and metre that enhances the sensual character of much of his poetry, ranging from delicate to wildly passionate, even in the same poem.

He was also a totally original thinker; an atheist revolutionary. He believed in the redistribution of wealth, equality between the sexes, free love, non-violent protest against tyranny, education through persuasion and example, and scientific experiment and discovery as the future of humankind. Nothing of this would be particularly controversial now, but during the Regency in Britain, a time when hypocrisy over sexual mores, religion and the supposed “natural” order of things was at its most sophisticated and stifling, his beliefs and, more importantly, his attempts to live by those beliefs flew in the face of what was considered acceptable. Consequently, he was branded mad, at best, or evil and devilish at worst.

Needless to say, he was neither. Always at odds with society, the struggle to live an authentic life could sometimes make Shelley blind to the needs of others, particularly to the women who loved him, but those generous and unselfish impulses Byron noted were more often than not the motivations of his life.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was born on 4 August 1792 in Field House, Wareham, West Sussex. His father Timothy was a well-to-do member of the gentry and aspiring liberal politician. His early childhood was in many ways idyllic, spent amongst his younger siblings, ranging across fields and down rivers, in pursuit of ideas or butterflies.

At Oxford in 1810, amongst the freshmen of University College, he found a kindred spirit in the shape of Thomas Jefferson Hogg, from a lawyerly family near Stockton-on-Tees. Hogg and he would stay up all night talking of free love and free thinking. Shelley conducted experiments in his room on the nature of galvanism and electricity to the horror of his scout. From the university curriculum, such as it was, they learned little, but they did learn to collaborate for the future of society. The fruits of this collaboration appeared as a little pamphlet called The Necessity of Atheism, an intriguing treatise which used the discipline of the English empiricist philosophers Locke and Hume to argue against the existence of a deity. A step too far for the crusty conservative atmosphere of Oxford then. When they refused either to acknowledge or deny their authorship of the anonymous pamphlet, both scholars were expelled from the university.

He knew the seductive power of lyric, the poignancy of the ballad, the exquisite, sensual charm of the love song

The struggle of Shelley’s authentic life began then.

And it began at home. He quarrelled with his father, who threw him out of the family home. Money was always short. Timothy Shelley was persuaded, albeit reluctantly, to restore his eldest son’s allowance, but the fledgling poet was always too generous with others and his little coterie left debts wherever they went. The sense of being persecuted, by his father, by creditors, by lawyers, by the government, would drive Shelley on from one place to another, never settled, never at home, with whomever was in love with him following like leaves driven by the west wind.

And it was during this period of wandering Shelley wrote his first major work of political thought, the long poem “Queen Mab” and its even longer “Notes” in which the poet set out his thoughts on atheism, love and vegetarianism. In a dream, the heroine Ianthe is whisked away by the Fairy Queen Mab to be shown the corruption of the world and the hope of a new horizon beyond:

Is turned to deadliest agony, old age

Shivers in selfish beauty’s loathing arms,

And youth’s corrupted impulses prepare

A life of horror from the blighting ban

Of commerce; whilst the pestilence that springs

From unenjoying sensualism, has filled

All human life with hydra-headed woes.

”Queen Mab” was published in several, not always accurate, editions during the 1820s and was hot reading for the Chartists and revolutionaries of the next generation long after the poet was dead. Not his best poem by any standards, it was certainly the most read in the 19th century because of its revolutionary content and the notes published with it.

Shelley’s second elopement – he had previously taken up with and married the schoolfriend of his sister, Harriet Westbrook, when he was 19 and she 16 – would be far more dramatic and fateful than his first. William Godwin, the father of the girl in question, had become a mentor but, had been dead set against any relationship between the already married Percy and his daughter, Mary. But Mary Godwin was in every way Shelley’s equal intellectually. She grasped easily what he wanted from life where Harriet had struggled.

They would have to travel, almost constantly, through Paris to Switzerland initially and then back up the Rhine, poor as church mice, constantly seeking the next opportunity, the next loan, the hoped-for publishing breakthrough, checking over their shoulders for bailiffs and court orders. Shelley would even spend a couple of nights in debtors’ prison. They would pass a celebrated summer with another famous social outcast, Lord Byron, on Lake Geneva in 1816, Mary dreaming up her most enduring creation, Frankenstein’s monster, Shelley signing himself at a string of hotels under the section marked “occupation” with “democrat, philanthropist, atheist”.

The sublime scenery around Mont Blanc, which had convinced so many others of the existence of a God, did the opposite for Shelley:

Which teaches awful doubt, or faith so mild,

So solemn, so serene, that man may be

But for such faith with nature reconciled;

Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal

Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood

By all, but which the wise, and great, and good

Interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel.

– “Mont Blanc”, 1816

Shelley’s return to England that autumn would be blighted by two tragic circumstances: the death Mary’s younger half-sister Fanny and the suicide of Harriet Shelley, who had been forgotten in the whirlwind romance with Mary Godwin. In an attempt to stave off criticism and create a respectable family for a coming custody battle, Shelley and Mary would marry, against all his principles, but a court would eventually grant custody of his and Harriet’s children to a foster family, citing his bad character and avowed atheism.

Shelley had taken his family to Italy in 1818 after a year of hardships and recriminations. His grandfather had died, leaving an estate which he would only inherit on the death of his father Timothy. On the back of that, however, he’d been able to secure significant loans. The little family included Claire Claremont – stepsister of Mary – as well as Shelley’s and Mary’s son William and daughter Clara – who would die soon after their arrival in Venice. William would also die in Rome in 1819, reducing the family to the three sad, bickering adults once more.

The time from his arrival in Rome in 1819 to his death off Viareggio three years later was Shelley’s most productive poetically. His political radicalism deepened but so did his ability to channel it through verse of exquisite rarity and power.

While in Rome in 1819 he wrote the bulk of what is possibly his finest work, Prometheus Unbound – both a response to the formal demands of Greek tragedy, specifically Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound in which the Titan Prometheus is punished by Zeus for his championing of humans by stealing fire from Olympus, and a commentary on the here and now of post-Napoleonic and post-Revolution Europe. The tortured hero overcomes the tyrannical god who chained him to a mountain to have his liver ripped out daily by an eagle by coming to an understanding that forgiveness is a surer way to victory than the thirst for revenge. The violence in his own nature, which had resulted in Prometheus uttering a terrible curse, is acknowledged and repented:

Grief for a while is blind, and so was mine.

I wish no living thing to suffer pain.

– Prometheus Unbound, Act I, 1819

Shelley’s championing of what we would now know as non-violent action is one of the many remarkable aspects of his thought, given that he lived in an age of violence, emerging from what up to that date had been the most violent war in history.

Written as a drama, Prometheus Unbound is hardly that. The action has a sort of inevitability about it. It is static and wordy. There are only two real characters in it, Prometheus and his beloved Asia, who are entirely in sympathy with each other if separated by circumstances. Everyone else who speaks does so as a manifestation of some part of their psyches. Ultimately, and in spite of the obvious political content whereby the overthrow of the tyrannical Jupiter is carried out by a shapeless creature called Demogorgon (whose name means ”people monster”), this poetic drama is as much about poetry and poetic beauty, the beauty specifically of lyric verse, that would flourish in a world devoid of cruelty and tyrannical power, as it is about non-violent revolution:

Down, down!

Like veiled lighting asleep,

Like the spark nursed in embers,

The last look Love remembers,

Like a diamond, which shines

On the dark wealth of mines,

A spell is treasured but for thee alone.

Down, down!

Once removed from the environs of the city of Rome and settled in and around Pisa in Tuscany, Shelley would dedicate his energies to writing the great odes, “To a Skylark” and “Ode to the West Wind”, as well as one of his most famous overtly political poems, so controversial it was never actually published in his lifetime for fear of prosecution. “The Masque of Anarchy” was Shelley’s response to the Peterloo Massacre of August 1819, in which a local militia of dragoons broke up a large peaceful political meeting in a field just outside Manchester with extreme violence.

That which slavery is, too well –

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own.

Tis to work and have such pay

As just keeps life from day to day

In your limbs, as in a cell

For the tyrants’ use to dwell,

So that ye for them are made,

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade,

With or without your own will, bent

To their defence and nourishment…

And at length when ye complain

With a murmur weak and vain

’Tis to see the Tyrant’s crew

Ride over your wives and you—

Blood is on the grass like dew.

Shelley’s final stanza contains the justly famous lines:

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many–they are few.

A few months later, in 1820, Shelley wrote to his friend Leigh Hunt, “I wish to ask you if you know of any bookseller who would like to publish a little volume of popular songs wholly political, and destined to awaken and direct the imagination of the reformers.” As if he already knew Hunt’s answer, he added, “I see you smile – but answer my question.” The climate was too shady in Britain for such a volume of “political” songs. The very form, the sing-song ballad-like verse of which Shelley was such an adept would have terrified most publishers at the time, keen to avoid the fates of those who’d been hanged for the slightest hint of sedition.

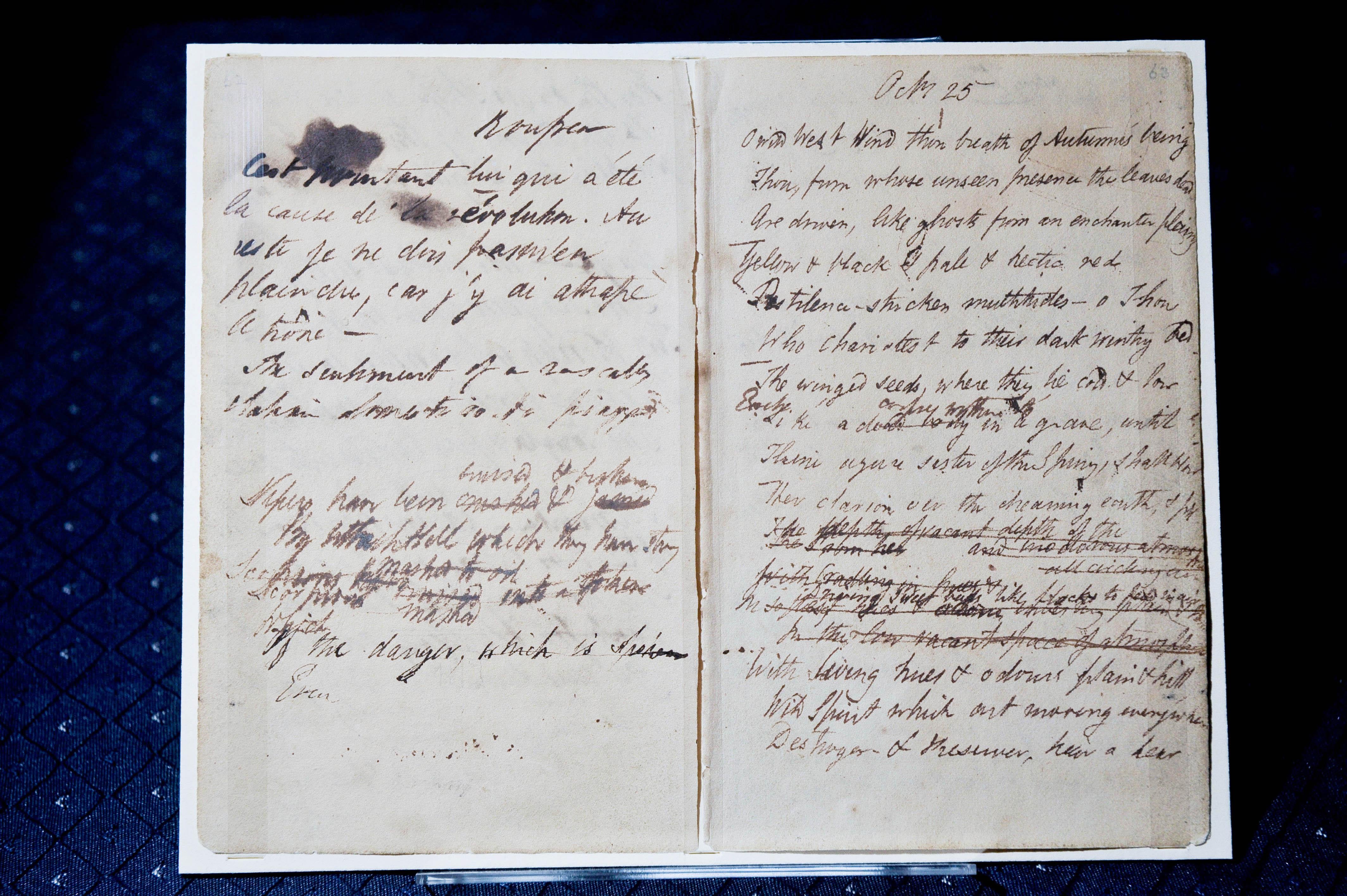

Instead, Shelley turned to more formal poetry, formal in the sense of a time-honoured, indeed ancient verse format that spoke to a more educated readership, but with the same purpose in mind. Keeping the theme of revolution, in “Ode to the West Wind”, written towards the end of 1819, Shelley projected the power of nature as a revolutionary force, sweeping all before it just as the spirit of the age would affect irrevocable change in human society.

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing…

Beset by financial problems, his relationship with Mary was strained, not least because of the continuing presence of her stepsister Claire, Shelley’s family moved from one place to another in the years 1819-1822. The payment of an annuity from his grandfather’s estate was not always forthcoming, leading to serious financial difficulties. The mauling of his long narrative poem “The Revolt of Islam” by the Tory press – a poem which explored how violence begat violence, violent revolution counter-revolutionary brutality to no purpose and no end – mirrored by their attacks on Keats’s poetry at the time, and finally the death of Keats in Rome in March 1821 slunk Shelley deeper into retrospection and what we would now call depression.

He rallied later that year to write a beautiful elegy for Keats, “Adonais”, something he’d been unable to do for his own son William. In fictionalising the poet as a sort of defunct beloved of the gods, however, Shelley was really writing as much about himself, the persecuted prophet of human kindness, the last passages even prophesying his own death in a storm at sea a little over a year later:

Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng

Whose sails were never to the tempest given;

The massy earth and sphered skies are riven!

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar…

– “Adonais”, 1821

Shelley was the poet of latency, the poet of revolutions to come, of energy just woken from a long sleep, of ideas unbounded. Much of what he wrote, from a political perspective, was a sort of exhortation to those reformers in England who waited too long – perhaps one reason why the reform movement, and Hunt in particular, were reticent about a wider reading of his poetry.

Radical writers and publishers would fight a sort of guerrilla war against successive governments in Britain, using the law, mass protest, courting imprisonment and gradually, slowly breaking down resistance to reform. It’s no surprise, therefore, that it was only in the years following his death that Shelley’s call for peaceful revolution, for a better deal for those who toiled, for a reform of political institutions on more equitable lines, and much, much later, for a recognition that men and women are entirely equal, was more widely understood, the meaning behind poems like “Queen Mab” and “Ode to the West Wind” better appreciated.

I said earlier that Shelley was the finest lyric poet of the century, and it’s that which transcends what could otherwise be political dogma in his verse. He knew the seductive power of lyric, the poignancy of the ballad, the exquisite, sensual charm of the love song. This last is the ultimate act of revolution, to cast off the shackles of power and violent reaction for a moment of pure union with another, to love, to rise for a while at least to another sphere of being, without prejudice, without pain, without judgement or fear. To revolt. To be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments