Has Morrissey ruined The Smiths?

The singer is martyring himself on a cross of his own making, but what does that mean for the legacy of the band that started Morrissey off, asks Sean Smith

Forty years on from their formation, The Smiths are still revered despite their lead singer’s apparent determination to tarnish their legacy.

Since his endorsement of the far right, few idols have fallen so far and so fast as Morrissey – from de facto leader of a generation to a quisling on the dark side of a culture war. Billy Bragg, a former admirer and colleague from the days of Red Wedge – a 1980s collective for musical artists fighting Thatcherism – even went so far as to dub him “The Oswald Mosley of Pop”.

Now that Morrissey's messiah complex has gone so horribly wrong there is surely no way back for the frontman. But where does that leave The Smiths and their legacy?

Had Johnny Marr not happened to watch a television documentary, The Smiths might never have happened at all. It was a South Bank Show epidoe on Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller – the legendary songwriting duo behind Elvis Presley’s electrifying early hits. Their partnership formed after Leiber had hunted down Stoller’s address, knocked on his front door and asked himself in for a chat.

Marr was so inspired by the tale that he resolved to do the same. On a quest to find a lyricist and lead singer, Marr kept coming across the name, Steven Morrissey. Morrissey was a half-forgotten figure on the fringe of Manchester’s music scene, best known for briefly fronting a punk band called The Nosebleeds.

Guided there by a mutual acquaintance, Marr arrived at 384 King’s Road in Stechford, South Manchester at around 1pm on a sunny weekday afternoon in May 1982.

If Marr hadn’t called that day, there’s a possibility that Morrissey would still be living there in the semi-detached council house he shared with his mother. Fast approaching his 23rd birthday, Morrissey was between jobs, going nowhere fast and often to be found at home in the middle of the day.

Although Marr cheerfully pointed out, “this is how Leiber and Stoller met,” Morrissey happened to remember him from a chance encounter nearly four years earlier.

Marr had made an unfavourable impression when they’d been queuing for a Patti Smith concert outside Manchester's Apollo theatre in August 1978. Coming across as something of Mancunian street urchin, Marr had slightly offended the eloquent Morrissey, by telling him he “spoke funny”.

But Marr was a much more credible figure now. Still only 18, he was already a seasoned veteran of several local bands and recognised around Manchester as a dazzlingly original guitarist.

Marr succeeded in gaining an audience and was admitted to Morrissey’s bedroom to discuss music. Although they had very different temperaments, they shared an obsession with 1960s girls group, and left-field artists like The Velvet Underground, The Stooges and David Bowie. “This wasn’t stuff we liked. This was stuff we lived for,” Marr would later explain in his autobiography, Set The Boy Free.

From their earliest moments there was a buzz around the band. The Smiths sounded so extraordinary that they bypassed that traditional phase of serving their apprenticeship and paying their dues

Their first songs were written at Marr’s rented rooms in Bowdon where Morrissey would arrive with sheets of fully formed lyrics. “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle” and “Suffer Little Children” would eventually feature on their debut album two years later.

By focusing on the grieving parents of children lost to the notorious Moors Murderers, Myra Hindley and Ian Brady, “Suffer Little Children” would generate enormous controversy in the British tabloids. The Sun would even accuse The Smiths of glorifying child murder.

And at a distance of forty years, it still seems a bizarre choice of subject matter for an inaugural composition. And yet, “Suffer Little Children” can also be seen as a mission statement that foreshadows The Smiths’ entire body of work.

The suffering of working class people trapped in desperate situations beyond their control would become Morrissey’s obsessively recurring theme. He would go on to make it every bit as worthy a subject for artistic treatment as a pastoral landscape.

“Suffer Little Children” is now regarded as one of the band’s most beautiful and haunting songs. Marr would remember its joint composition as a wondrous moment where the writing partnership’s magical alchemy first began to exert itself.

“Something was coming through the ether – a song that didn’t sound like anyone else and feel like anyone else,” he would later write.

Over the early summer of 1982, the duo would continue to meet and compose songs that Marr would capture on a crude recording device.

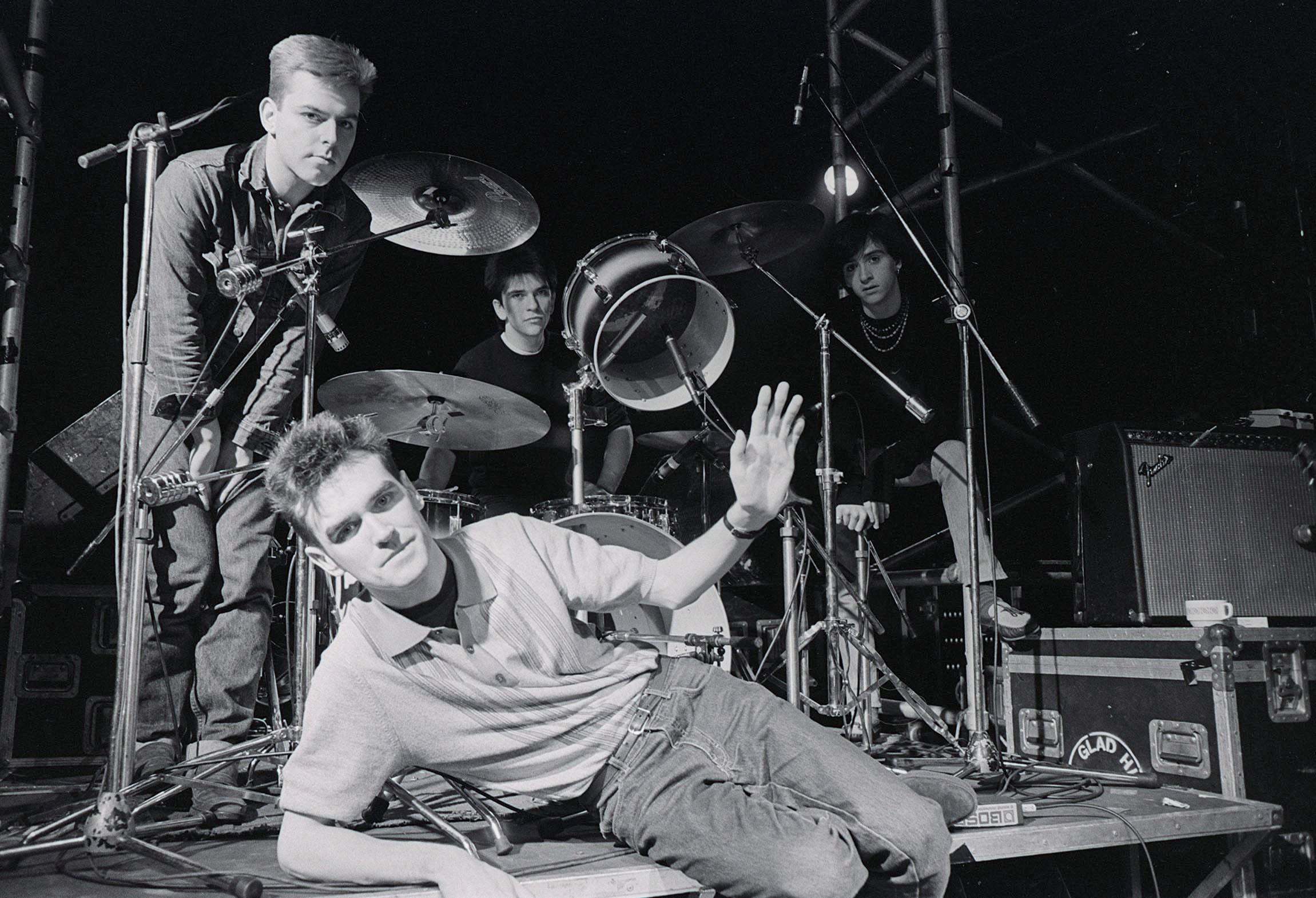

As a well-known face on the Manchester music scene, Marr would take the lead in auditioning for other members, eventually settling on Mike Joyce as drummer and his old school friend, Andy Rourke on bass.

By the end of the year, the now familiar line-up was in place. From the moment they first played together at rehearsals, Morrissey experienced an intoxicating sense of freedom. He was exhilarated by the band’s “bomb-burst drumming, explosive chords, combative basslines,” saying that, “over it all I am as free as hawk to paint the canvas as I wish.”

Early songs like “Handsome Devil” and “These Things Take Time” showcased Morrissey’s volatile vocals ricocheting off Marr’s guitar set against the tightly locked-in rhythm section of Rourke and Joyce.

From their earliest moments there was a buzz around the band. The Smiths sounded so extraordinary that they bypassed that traditional phase of serving their apprenticeship and paying their dues.

But it was the song “Hand in Glove” that would change their lives forever.

The independent record label Rough Trade released their privately recorded demo as a single. When Morrissey first heard “Hand in Glove” being played on the radio he would acknowledge the extent to which Marr had liberated him from the depths of despair. In his book, Autobiography, he would compare it to, “a disfigured beast finally unchained from the ocean floor.”

“Hand in Glove” was followed in quick succession by a string of songs that would lodge in the lower reaches of the charts but later be acknowledged as among the greatest singles of all time. “This Charming Man”, “What Difference Does it Make?” and “William it was Really Nothing”

So prolific were The Smiths that “How Soon is Now” – often regarded as their best song – was only deemed worthy of a 12-inch B-side release,

Signing with the independent label, Rough Trade, was a statement of autonomy, and integrity – a declaration that the music mattered far more than mere commercial success.

The Smiths were quickly adopted as the darlings of the music press and championed by John Peel on his Radio 1 show that celebrated new music away from the mainstream.

Peel regarded The Smiths as a wonderful anomaly with a sound so distinctive it seemed to have appeared out of nowhere. “You couldn't immediately tell what records they’d been listening to. That’s very rare indeed. It was that aspect of The Smiths that I found most impressive.”

But The Smiths were as much a movement as a band – a ready-made sensibility built around the personality cult of its lead singer

But it’s easy to forget just how polarising The Smiths were at the time.

The charts were dominated by bands like Duran Duran and Wham, slick, commercial machines calibrated to part their fans from their money. They shifted millions of units marketing themselves through expensive videos shot in impossibly exotic locations.

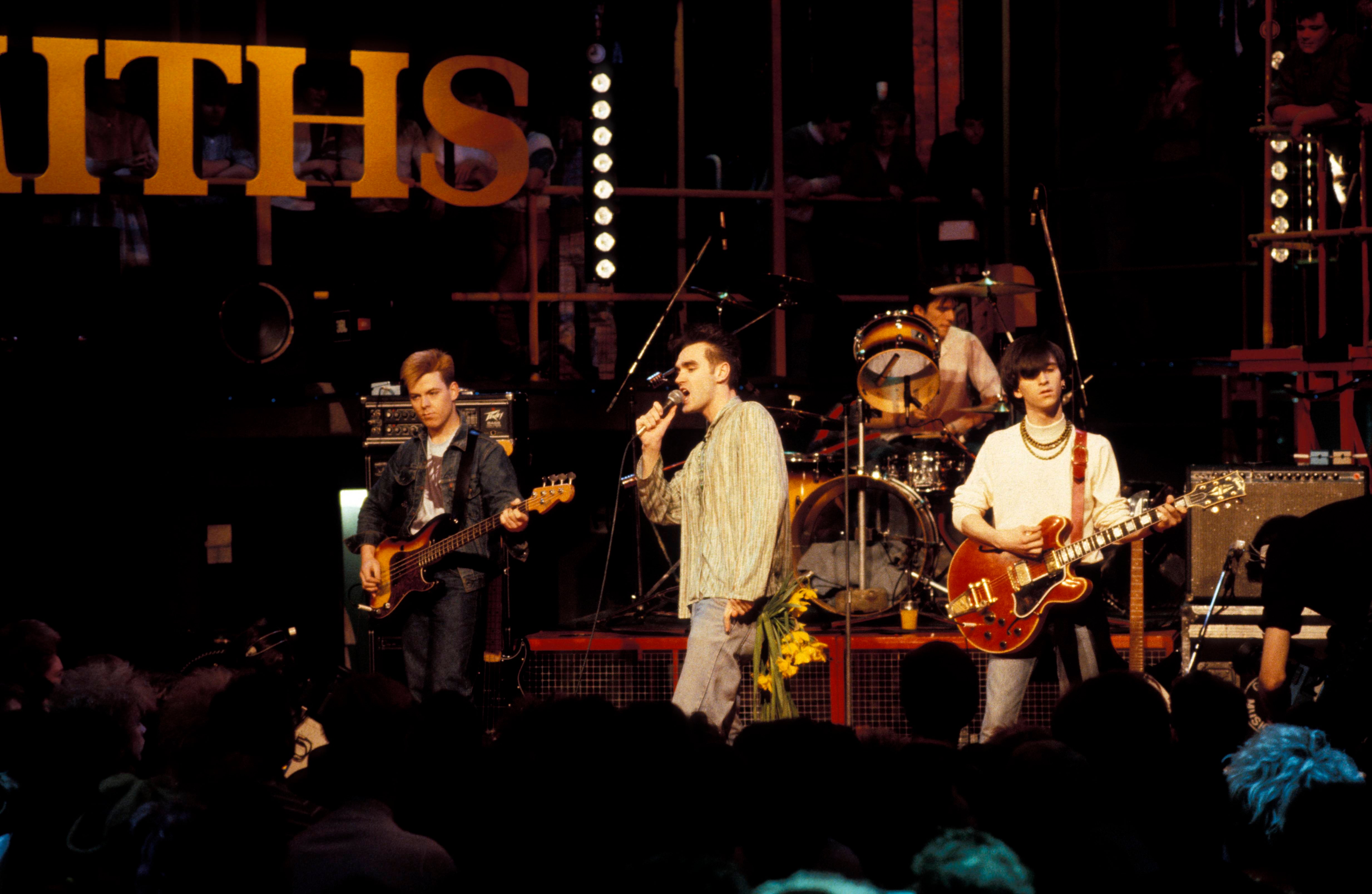

In contrast, The Smiths turned up for their Top of the Pops studio appearances, defiantly dressed down in jeans. To the bemusement of the teenage studio audience and the watching public at home, Morrissey would gyrate like a stick insect gurning at the camera, spinning a gladiola while decked out with a hearing aid and national health spectacles.

At my school – as I’m sure was the case at many others – The Smiths were viewed with suspicion and the consensus seemed to be that the effete lead singer was a bit of a “prat”.

Classmates would swap CDs by massive mainstream acts like Dire Straits, Level 42, Genesis and Queen. Arguments over who were the best band tended to bizarrely obsess about chart positions or who had the best video. But their songs themselves meant nothing to me and left me cold; and in our house, we couldn’t afford a CD player anyway.

My life changed when Rough Trade released Hatful of Hollow a collection of The Smiths’ BBC sessions. Listening to a borrowed vinyl version made the hair stand up on the back of my neck; it still does. I hadn’t realised that music could make you feel like that.

But The Smiths were as much a movement as a band – a ready-made sensibility built around the personality cult of its lead singer.

Morrissey was obviously very intelligent and an arch manipulator of the music press using the NME, Melody Maker and the Record Mirror to publicise the band and promote his strident views and radicalising a generation of young people.

The Smiths were certainly of the left, and although they never aligned to a specific political party, they did support the Red Wedge. Morrissey was an outspoken critic of the prime minister in particular.

“The sorrow of the IRA Brighton bombing is that Thatcher escaped unscathed,” he told one astonished interviewer.

On another occasion he skewered Bob Geldof and Band Aid for their attempts at famine relief.

“One can have great concern for the people of Ethiopia, but it’s another thing to inflict daily torture on the people of England.”

Every interview was a chance for Morrissey to hone his aphorisms in modern day homage to Oscar Wilde.

For many a working-class kid in the 1980s, The Smiths were a gateway through which you accessed culture as curated by Morrissey. He was a one-stop shop for recommendations of records, books, politics and film.

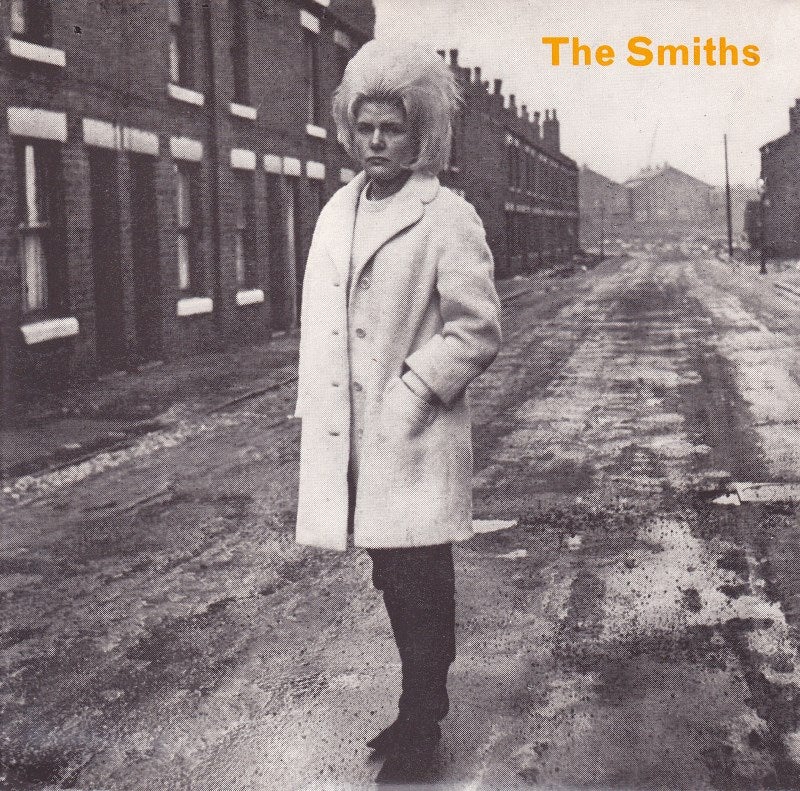

The Smiths’ record sleeves introduced a generation of fans to the kitchen sink dramas of Shelagh Delaney and the northern realism films of the 1960s. Record sleeve cover stars were like Morrissey, edgy, bright working-class heroes, like Pat Phoenix or Viv Nicholson who refused to acquiesce or be ground down by the situations they found themselves in.

It’s widely believed that the release of their second album Meat is Murder in 1985 helped create tens of thousands of vegetarians. Decades before the term came into popular use The Smiths were an advanced party in a culture war with Morrissey straddling the frontline on wedge issues like animal welfare, gender politics and class war.

By the time The Queen is Dead was released in 1986, The Smiths had far fewer detractors. It’s now regarded as one of the greatest recordings in the history of popular music. And after just one more great studio album – Strangeways, Here We Come – The Smiths split up with Morrissey and Marr unable or unwilling to reconcile their differences.

There’s a pleasing symmetry to the fact that The Smiths began and ended with an episode of revered arts documentary, The South Bank Show.

Just over five years on from the edition on Leiber and Stoller that had so inspired Johnny Marr, The South Bank Show episode on The Smiths effectively became a memorial to their recent passing in the summer of 1987.

Not many rock bands merited a South Bank Show but the documentary compared them to Bob Dylan and The Beatles, predicting that one day they’d be recognised as part of a tiny elite who had elevated popular music to the status of a true artform.

When Cameron praised The Smiths’ sense of mischief it wasn’t just a case of cultural misappropriation: it felt more like a hostile takeover or an act of annexation

When I was a student in Manchester in the early 1990s, The Smiths were gone but not forgotten. In terms of music and youth culture, Manchester seemed to be the centre of the universe. For me, and for so many of the people I met there, it was The Smiths that had exerted most of the gravitational pull that had drawn us there.

It was as if the city that had been staggered by industrial decline under Thatcherism was using its music to drive entropy into reverse. Manchester was levelling itself with a sense of its swaggering self-confidence led by The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, The Charlatans and later Oasis – independent-minded bands who would come to define the era.

With each passing year, The Smiths became increasingly revered and cited as an influence by bands that dominated the 1990s.

By the start of the new millennium, The Smiths were in serious danger of becoming national treasures. In 2002, The NME voted them the most influential musical act of all time.

And in a 2006, in BBC poll to find the greatest Briton of all time, Morrissey was the runner-up to David Attenborough.

But the “main-streamification” of The Smiths reached disturbing new heights when the Conservative prime minister, David Cameron, outed himself as a Smiths fan in 2010.

When Cameron praised The Smiths’ sense of mischief it wasn’t just a case of cultural misappropriation: it felt more like a hostile takeover or an act of annexation by the establishment.

Marr took to Twitter to take issue with the prime minister: “David Cameron, stop saying that you like The Smiths, no you don’t. I forbid you.”

But Morrissey’s little Englander mutterings about unchecked immigration changing the character of British culture would become harder to ignore.

In the modern-day culture wars, Morrissey’s emergence as, first, a critic of immigration, then a supporter of Nigel Farage, and finally an endorser of the proscribed far-right organisation For Britain put him on the wrong side of history – far beyond the pale.

It’s so sad to see the once scourge of The Daily Mail's middle England readership become such an espouser of its core values. For Smiths fans of a certain age, it feels disorientating almost as if one of the struts holding your identity together has been taken away.

Perhaps The Smiths will be remembered as the last of the working-class heroes in an era when a working-class hero truly was something to be.

They’ll certainly be remembered. That’s the thing about culture – it has a life of its own seizing on the things of beauty that will be a joy forever.

Culture isn’t controlled by anybody; even the people who created its greatest works of art ultimately have no claim over them. That’s why we can appreciate the plays of Shakespeare while knowing virtually nothing about the man who wrote them. So if we have to separate the singer from the songs, so be it.

Generally, racists are such poor custodians of “the culture” they claim to be protecting because they don’t realise that culture is a living entity forever growing, changing and renewing itself; it can’t be controlled. Ironically, that’s why a unique anomaly like The Smiths were able to come out of nowhere to transform popular music forty years ago.

Marr is right to say: “You can’t change history. The songs are out there for people to judge.” It’s hard to believe that we’ll ever see their like again.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks