Losing Britain’s archaeological ‘Atlantis’

Offshore wind farms may be good news for the environment but they’re worrying developments for the archaeologists trying to map Mesolithic remains, reports Sean Smith

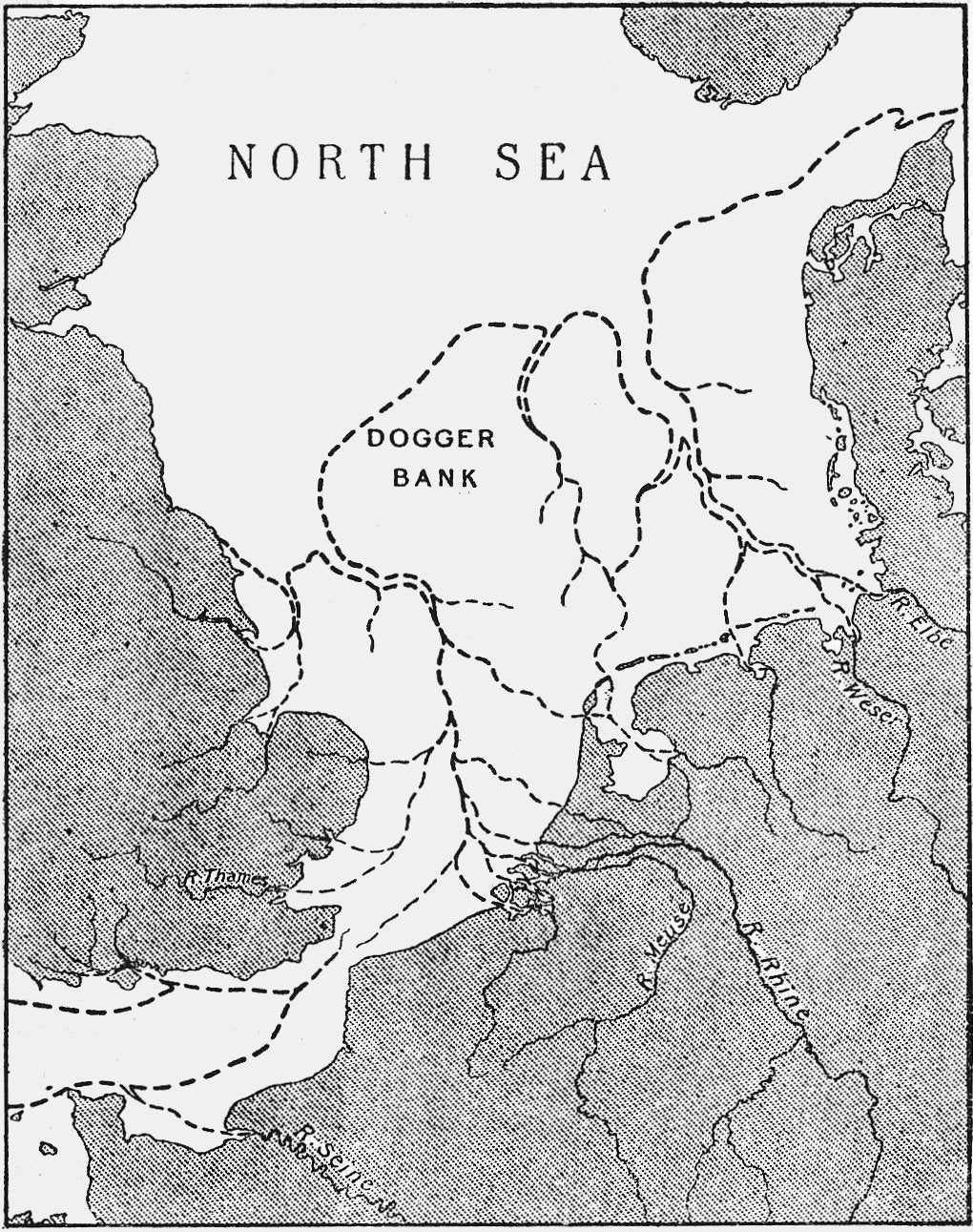

Just over 10,000 years ago Britain emerged from the last ice age as a hilly hinterland still attached to Europe by the vast, low-lying landmass that is now known as Doggerland. As the climate warmed and the ice sheets retreated, Doggerland would have gradually been transformed from a bleak tundra to a rich and varied landscape.

Because sea levels would have been so much lower than today, it would have been possible to walk from Yorkshire all the way to Denmark through valleys, lakes, woodlands and Marshes.

With its wealth of fish, eels, birds, otters , seals, deer, wild boar and berries, archaeologists believe that Doggerland was so prime a location that its Mesolithic hunter-gatherers started to transition away from a nomadic culture towards a more settled way of life.

But continued global warming transformed the low-lying terrain over just a few millennia. Rising sea levels gradually moistened Doggerland into a landscape of ever-expanding rivers, lagoons and wetlands and eventually an ever diminishing archipelago of low-lying islands before its highest points finally disappeared beneath the waves around 5500 BCE. By then, Doggerland’s inhabitants would have safely migrated to the coasts of Denmark, Belgium, France, Germany and Britain.

The modern legend of a lost land beneath the North Sea can be traced back to the middle ages. Petrified tree stumps – visible just off the coast of England at low tide – were christened “Noah's Woods” because medieval coastal dwellers regarded them as evidence of the biblical flood.

In A Story of the Stone Age in 1897 HG Wells relates the adventures of the inhabitants of a valley that is now beneath the English Channel. In Submerged Forests (1913), Clement Reid became the first geologist to theorise that “nothing but a change in sea level” would account for the position of the tree stumps and argued that Noah's Woods must have stretched all the way across the North Sea to the Netherlands and Denmark.

The first archaeological artefact to confirm Reid's theory was discovered in 1931, when a British fishing trawler called The Colinda dredged up a serrated harpoon carefully crafted from antler – it was later found to date from the Mesolithic era between 10,000 and 4000BCE. The fact that the harpoon was embedded in a freshwater peat deposit established that it had been buried in a terrestrial landscape.

The fishing technique of beam trawling entails dragging heavy nets along sea beds and disinterred other intriguing artefacts. Textile fragments and an ancient canoe paddle were also discovered nearby. Another well-known Mesolithic site was discovered off the coast of Denmark where sunken floors, canoes and burial sites were found next to an ancient riverbed.

Crisscrossed by high-speed internet cables and shipping lanes, Doggerland is still yielding up its secrets today. Chance archaeological finds are still trawled up by fishing boats or washed up on Dutch and English shores offering tantalising glimpses of its mysterious Mesolithic culture. At low tide, petrified prehistoric tree stumps are still visible off the coast of Redcar and Hartlepool.

The Mesolithic era dates from 15,000 to 5,000 years ago and has only been recognised as a discrete archaeological period relatively recently.

While our older Palaeolithic ancestors made an indelible mark on the stone age with their distinctive tools and cave art and our more recent Neolithic forebears founded the first farming settlements, in contrast, the intervening Mesolithic era has left far fewer traces.

The predominantly nomadic culture of its communities means that very few archaeological sites have been recovered.

On land, potential Mesolithic sites have been lost to progress and buried under the generational tonnage of evolving infrastructure. But the last flourishing of Doggerland before its final submergence 7,000 years ago means that it is, in effect, a Mesolithic time capsule, perfectly preserved in its peaty soil under a sea bed of silt and sand.

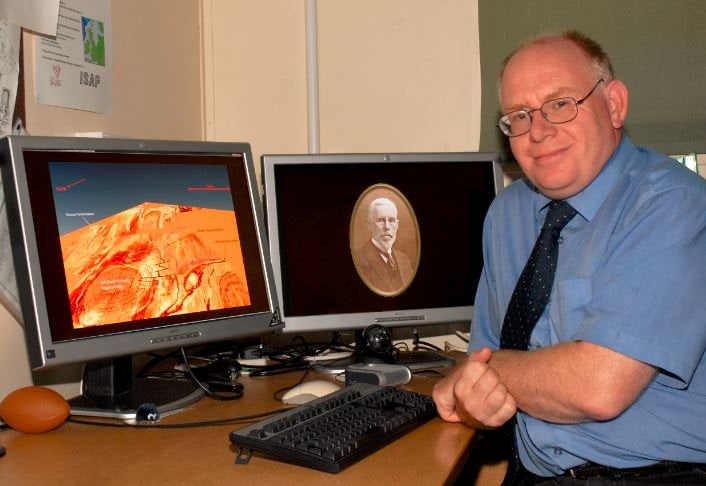

Professor Vince Gaffney, anniversary chair in landscape archaeology at the University of Bradford, explains that – archaeologically speaking – the Mesolithic era is something of a missing link because it occurred at such a pivotal and formative point in human history.

It certainly would have been a very bad day for you if you were standing on the shoreline when the Storegga slide happened

“At the start of the Mesolithic period, the world was a different shape but by the end it had taken on the shape we know today. At its beginning, 100 per cent of the human population were hunter-gatherers but by the end they were farmers. It’s a massively important part of the story,” he says.

It had been thought that Doggerland had suddenly been consigned to its watery grave as a result of a series of subterranean landslides off the Norwegian coast. Collectively known as the Storegga slide, the subsequent series of Mega Tsunamis devastated the coasts of England and the Netherlands around 8,200 years ago.

But Gaffney's team have been influential in establishing that Doggerland's highest points almost certainly survived that inundation

”It certainly would have been a very bad day for you if you were standing on the shoreline when the Storegga slide happened, but it could have been observed safely from Doggerland’s highest points,” he says.

Dogger Bank is one of those highest points and remains a modern-day hazard to larger vessels because it is just 15m below the North Sea’s surface.

Given that those higher points were the last dry land to become submerged around 5000BCE, they’re also of intense interest to archaeologists like Gaffney because they would have been optimal sites for Mesolithic settlements.

Another accessible site of enormous interest is the 15-mile-long seafloor ridge known as Brown Bank which lies roughly 100km due east from Great Yarmouth and 80km west of the Dutch coast.

Like Dogger Bank, Brown Bank is believed to have been high enough to survive the Storegga slide. It is also of enormous interest to archaeologists because the quantities of flora and fauna discovered there strongly suggest a prehistoric settlement.

Parts of Brown Bank overlooked an ancient river. Chemical and DNA analysis of material discovered there has led Gaffney’s team to speculate that its inhabitants were much less nomadic and much more likely to stay in one spot, even adapting a more fish-based diet.

For the last two decades, Gaffney and his team have been engaged in a quest to find Mesolithic settlements which he regards as, “one of the last great archaeological challenges in Europe”.

Confronted with a search area of tens of thousands of square miles – it initially seemed a daunting prospect especially given that the North Sea’s murky waters aren't conducive to searches by diving teams.

But when PGS (Petroleum Geo-Services) agreed to share their geophysical mapping surveys with Gaffney and his colleagues everything changed. Amassed at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars, the huge seismic surveys covered vast swathes of the North Sea basin.

By analysing the vast data set, Gaffney's teams at first Birmingham and then Bradford University have digitally reconstructed 45,000 sq km of a prehistoric landscape mapping hills, rivers and valleys – that's an area larger than the Netherlands.

Although establishing the lie of the land beneath the sea is an enormous achievement, Gaffney acknowledges that it's just the start: “At the moment we have an ordnance survey map without any of the settlements.”

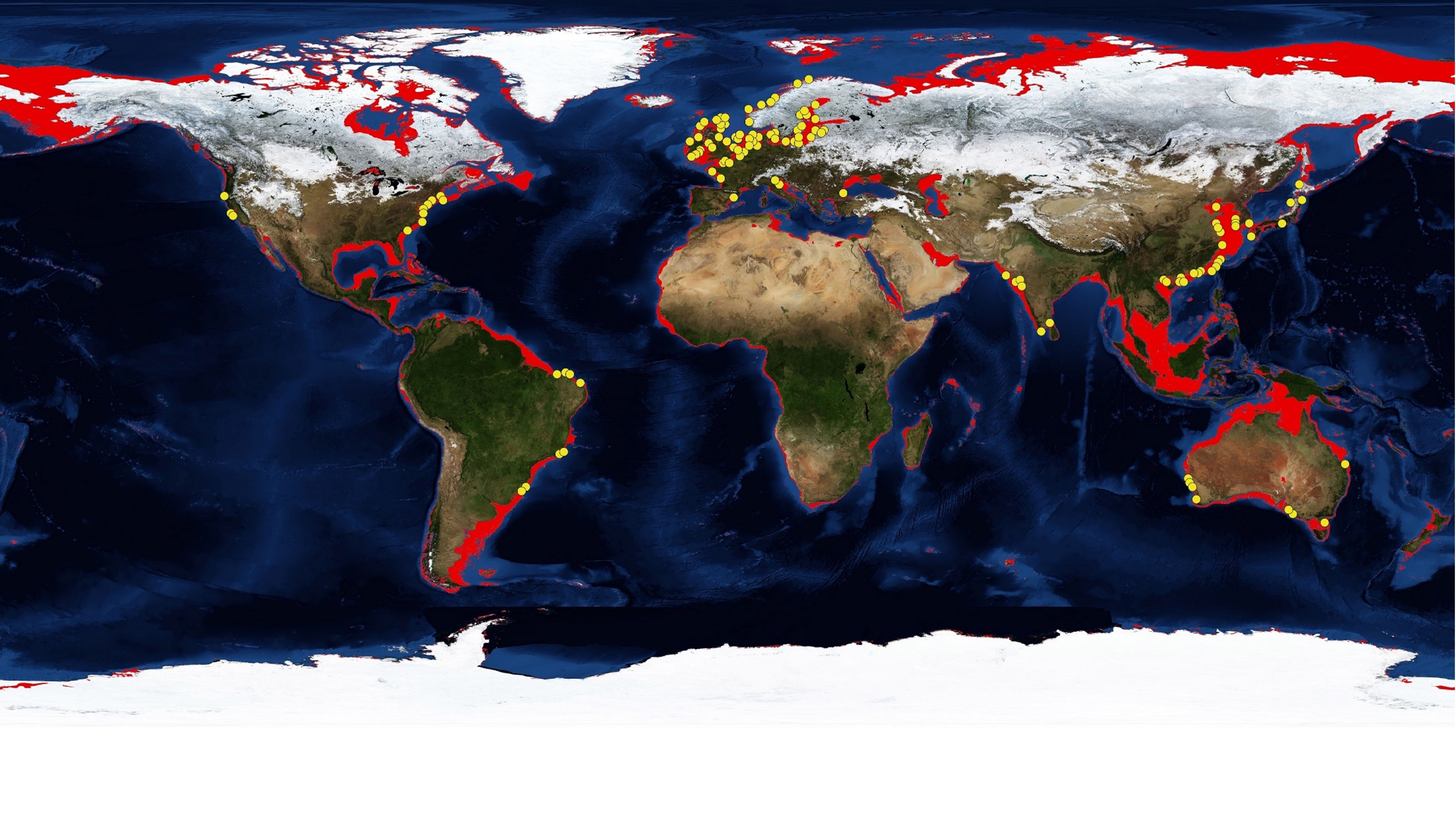

According to Gaffney, there are no known archaeological settlement sites from any period anywhere in the world located more than 12km offshore or deeper than 20m.

He explains that the difficulties involved in underwater archaeology has meant that they can only search, “in an archaeological Goldilocks zone where people were most likely to have been but also in areas that we can realistically access.”

Hopes of unlocking Doggerland’s Mesolithic secrets may be about to become another casualty of the Russian invasion

Gaffney and his team knew that the places they were most likely to encounter Mesolithic activity were located on what had once been high ground close to rich wetland resources. “Estuaries of rivers are very likely to be areas where people would congregate,” he says.

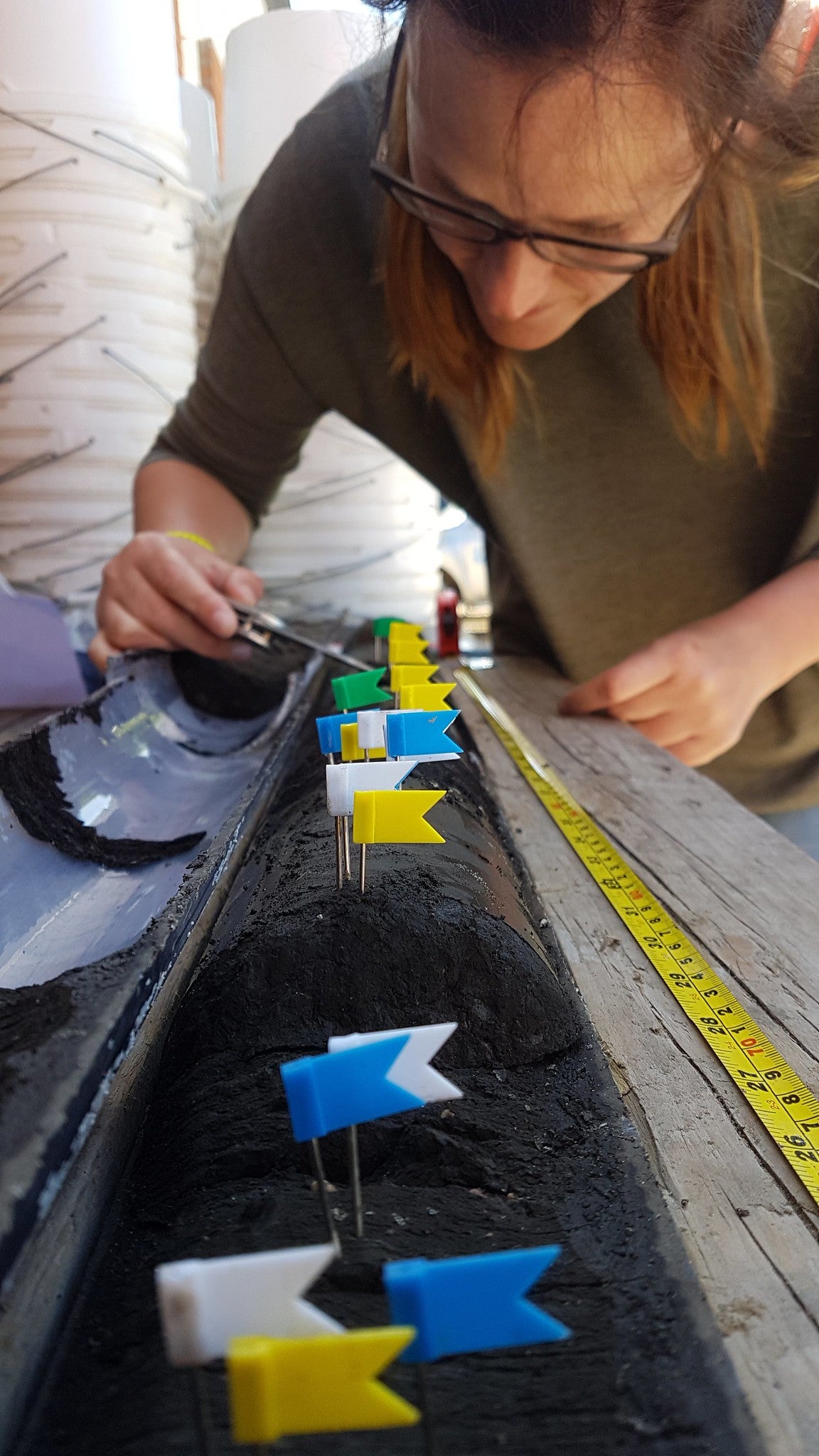

By joining a Belgian navy ship in 2019, Gaffney’s team were able to survey an ancient riverbed that’s buried 25 miles off the Norfolk coast. Despite very challenging weather – they almost immediately recovered a hammerstone – a Mesolithic stone tool used to fashion other implements.

Up to that point, all of the artefacts that have been recovered from Doggerland had been chance finds picked up by trawlers or washed up on shores. The discovery was so significant because Gaffney’s team had become the first to make a prospected archaeological find in a deep-sea environment.

For Gaffney, it was a vindication of his team's overall approach and a model of targeted prospecting that could be replicated in the rest of Doggerland's most promising and accessible archaeological sites.

But just as tantalising glimpses of Mesolithic culture were coming into sharper focus their research was halted by two consecutive global emergencies. The pandemic stymied attempts to further investigate the region but it's the implications of very recent events in Ukraine that pose the most serious threats to their research.

Hopes of unlocking Doggerland’s Mesolithic secrets may be about to become another casualty of the Russian invasion.

Gaffney completely understands Europe's determination to free itself from dependence on Russian oil and gas supplies. The prime minister, Boris Johnson, had been expected to announce an energy security strategy that expanded the use of nuclear power and onshore wind power but instead was forced into a U-turn because of the policy's unpopularity in rural Tory heartlands where wind turbines are regarded as eyesores.

When the long-awaited new energy strategy was finally published on 6 April, it rowed back on the commitment to onshore wind even though it is widely seen as the cheapest way to generate renewable energy.

Instead, the strategy announced plans to increase Britain's offshore wind power dramatically by 2030 with new planning reforms, slashing approval times for new offshore wind farms.

Although Gaffney welcomes the UK’s newly restated commitment to renewable energy sources as good news for the global environment, it’s also an alarming development for Mesolithic archaeologists because the shallowness of the water above those all-important raised banks means that they are also prime locations for offshore wind farms.

By 2030, it’s likely that the southern part of the North Sea will be almost entirely covered by wind farms, which will mean that its Mesolithic archaeological sites will no longer be viable.

“All of these pylons will be connected by a grid of tables to support green energy,” he says. “The whole of the North Sea is going to be developed for renewable wind energy. We’re going to lose the opportunity to map vast areas that are without any recorded archaeology even though we know it’s there.”

Gaffney and his colleagues are lobbying hard for a dialogue with offshore wind developers so that they can move quickly to protect access to Doggerland’s past: “We have to work with developers in the same way we do on land. If we don’t act now, large areas of seascape will be lost, essentially forever.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks