The fashion capital of the prehistoric world has been revealed

How Stonehenge-era Europe’s largest settlement thrived on ivory, gold rock crystal and amber

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Archaeologists have been unearthing what appears to have been the fashion capital of the prehistoric world.

Dating back some 5,000 years, the site – a Copper Age settlement in what is now southern Spain – has produced the largest concentration of upmarket prehistoric fashion goods ever found.

So far, literally hundreds of spectacularly beautiful gold, ivory, rock-crystal, amber, greenstone, sea-shell, ostrich eggshell, flint and copper artefacts have been unearthed – despite the fact that only around 1 per cent of the site has so far been excavated.

The detailed excavations, which have been going on for the past two decades, suggest that the site was a major international trade hub, attracting merchandise from literally thousands of miles away. Scientific tests have revealed that the most exotic raw materials for the most upmarket fashion accessories, came from as far afield as Western Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Sicily and northern Spain.

So far, archaeologists – from the Spanish universities of Seville and Huelva and from Germany – have found dozens of deeply buried complete and fragmentary ivory figurines, drinking cups and ornamental combs, as well as jewellery and luxury furniture and garment decorations Most of the ivory is from African elephants – but some are from Asian ones, which at that time still roamed the grasslands of western Asia. Archaeologists and other scientists from five UK universities and other research institutions have helped date and analyse many of the key finds.

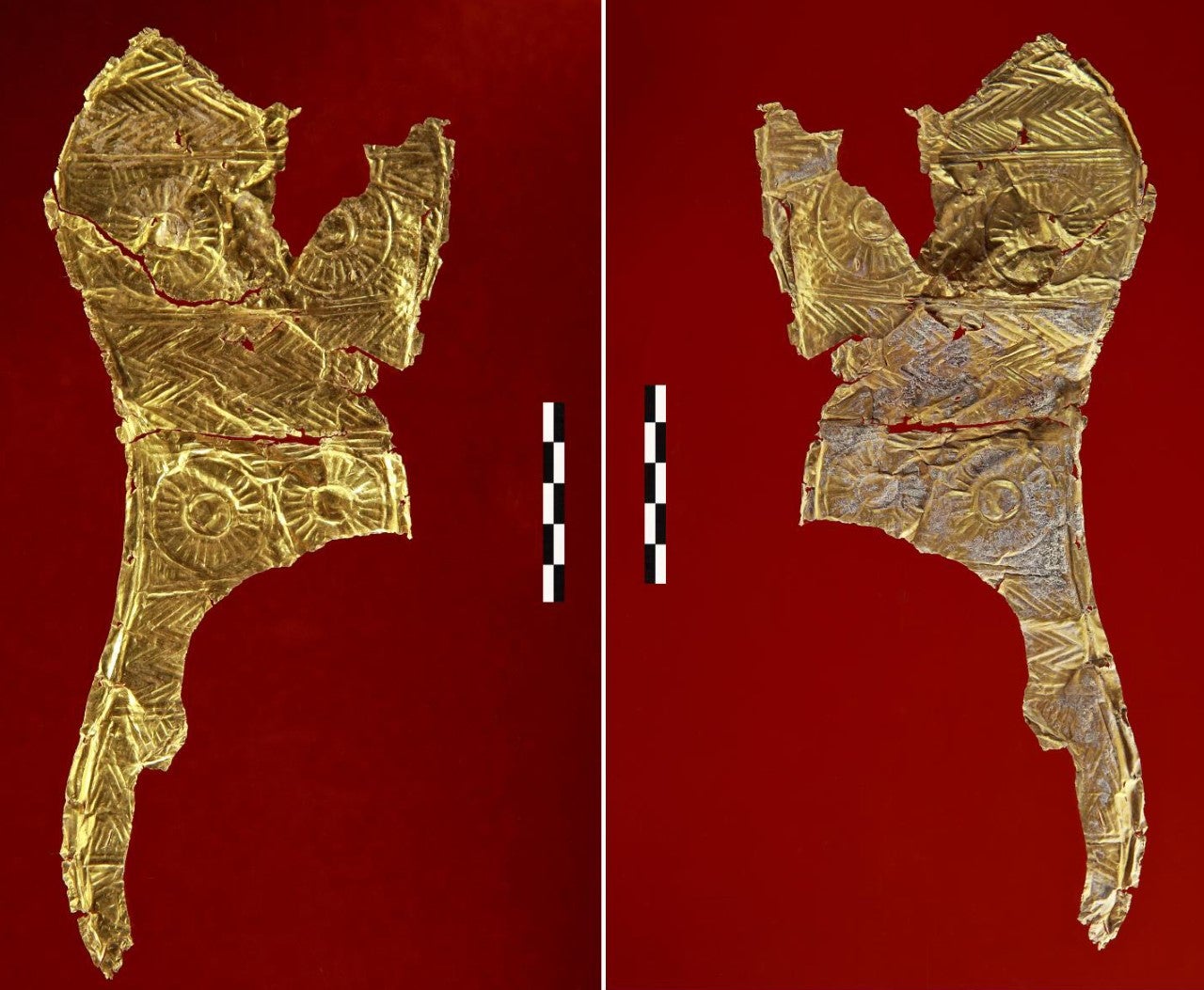

Gold – probably from southwest Spain – was used to produce eye-shaped solar religious symbols made of gold foil. The site has so far yielded two of these highly prized artefacts, the only ones ever found in western Europe.

The archaeologists have also unearthed dozens of beautiful amber beads, probably imported from Sicily. They are believed to have been used for jewellery and as decoration on high-class garments.

Other beads were made of rare green variscite (aluminium phosphate) gemstones, imported from northern Spain.

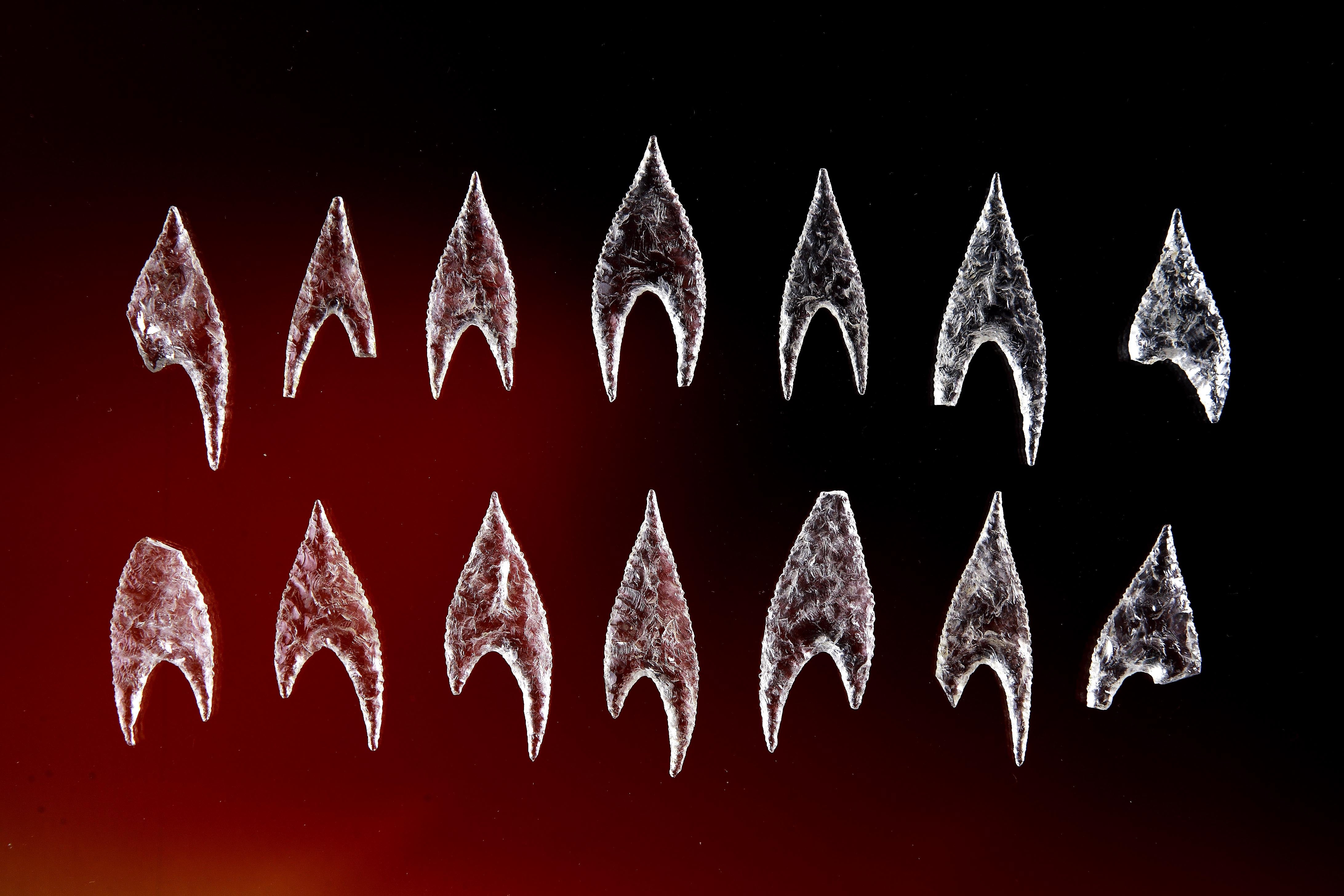

The excavations have also yielded other spectacular artefacts – ceremonial arrowheads, miniature blades and a dagger – made out of pure rock crystal, potentially imported from central Spain.

Large deep-sea scallop shells were also highly prized by the prehistoric settlement’s inhabitants – and were almost certainly imported from what is now Spain or Portugal’s Atlantic coast.

So far, the archaeologists have unearthed well over 100 very fine copper knives, axes, punches and spearheads. Although they are mostly made of local southwest Spanish copper, some of the most spectacular copper items (the spearheads) were manufactured in eastern Mediterranean style. Most of the spearheads are unusually long (20-27 cms) – and in a style previously only known from what is now Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Israel.

The scientific investigation of the site – located between the towns of Castilleja de Guzman and Valencina de la Concepción near Seville – is also revealing the makeup of the settlement’s population. Not only did the high-end fashion raw materials come from many different areas – but around 33 per cent of the settlement’s people were also non-local. This has been revealed through an isotopic study of skeletons, buried in the ancient settlement – but it is not yet known whether they came from elsewhere in Spain or from overseas.

The archaeologists even discovered that, in death as in life, the prehistoric settlement’s inhabitants went in for exotic fashion statements – by having their corpses painted in a valuable bright red pigment (cinnabar), specially imported from central Spain. The interiors of the settlement’s religious buildings were also adorned with this same high-status red paint.

At its peak, around 4,500 years ago, the ancient settlement covered more than 400 hectares (1.5 square miles) and may have had a permanent or fluctuating population of up to several thousand. It almost certainly had multiple functions – religious, ceremonial, commercial and political. In terms of physical size, it seems to have been the largest settlement of its time in western Europe.

However, only four hectares have been fully excavated so far – but that tiny area has yielded extraordinarily large amounts of information and artefacts (tens of thousands of fragments and complete items). Thousands of storage and ritual pits, several miles of massive ditches, hundreds of tombs and other features have so far been discovered. The excavations have been complex, partly because all the archaeological material is very deeply buried – more than two metres below the modern ground surface.

The settlement first came into existence in the late Neolithic (around 3200BC). After rapid growth, it became culturally, economically and politically important for much of the third millennium BC – but came to a relatively abrupt end in around 2350BC.

At its peak, it flourished at around the same time that Stonehenge was being built.

Its collapse is a mystery that only future archaeological investigations may solve.

However, climatic changes (and their economic, political and other consequences) almost certainly played some part in the settlement’s demise.

“Valencina is one of the most important prehistoric sites in Europe for helping us understand the rise of socially complex societies in our continent. It is yielding crucial evidence about the relationship between monumental buildings, ritual practices and exotic wealth which will enable us to better understand some of Europe’s earliest political and religious systems,” said the leading archaeologist currently studying the site, Professor Leonardo García Sanjuán of the University of Seville.

Ongoing scientific research on finds from the site is now beginning to shed new light on prehistoric social systems – especially whether they were patriarchal or matriarchal. Researchers are also investigating whether, as well as importing ivory from overseas, Valencina’s Copper Age craftsmen also exploited fossilised ivory from elephants that had lived in Spain hundreds of thousands of years earlier.

In the UK, research on material from the site has been carried out by archaeologists from Cardiff, Southampton and Durham universities – and dating work on key finds has been undertaken by the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre near Glasgow and by Oxford University’s Research Laboratory for Archaeology.

The research at Valencina is also helping scholars to better understand a much wider prehistoric civilisation that flourished in southern Spain some 4,000 to 6,000 years ago, the spectacular remains of which can still be seen today. As well as a remarkable subterranean ritual monument (the Dolmen de La Pastora) at Valencina itself, visitors can also explore the great funerary Dolmen de Soto near Huelva, the ruined Copper Age town of Los Millares (near Almeria) and the Unesco World Heritage prehistoric complex near Antequera, 30 miles north of Malaga.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments