The Russian scientist who put the first man in space ‘didn’t exist’

Sixty years ago today Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space and the most celebrated person on the planet. But who was the brains behind the project? Mick O’Hare on the ‘chief designer’ whose very existence was denied by the politburo

In April 1961 Major Yuri Gagarin of the Soviet Air Force was the most celebrated person on the planet. The Beatles, to much opprobrium, later joked they were more famous than Jesus. Well, contemporary polls showed that Gagarin really was. Sixty years ago he had just become the first human to fly in space and his stock soared – immortality guaranteed. Meanwhile, the Kremlin claimed communism to be the technologically superior doctrine as the Soviet Union basked in the kudos of having put the first man into orbit.

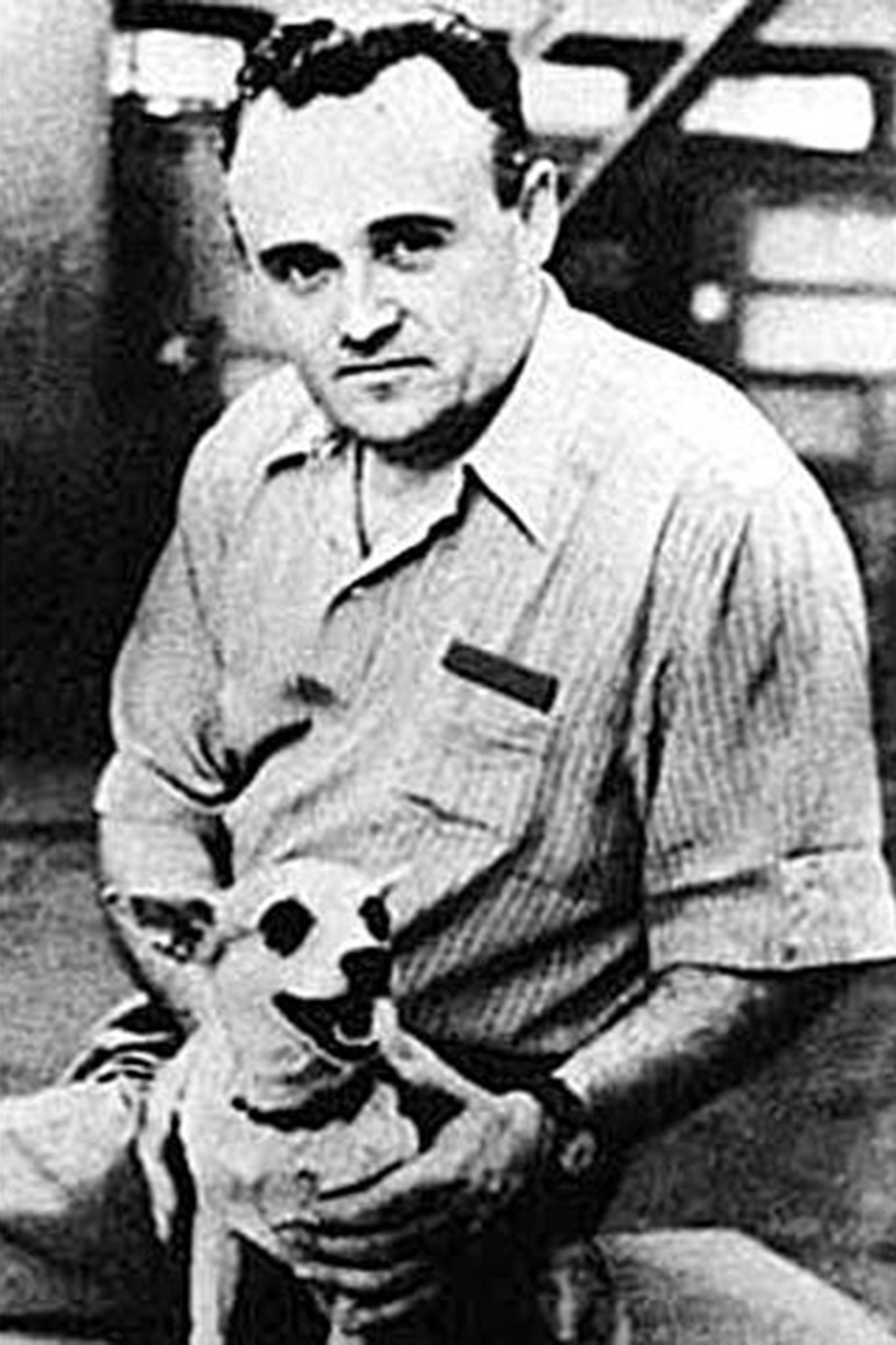

But what about the person responsible for putting him there? Only a handful of people knew he even existed. Sergei Pavlovich Korolev was the obverse of Yuri Gagarin, his obscurity antithetical to Gagarin’s fame.

Gagarin, the good-looking peasant’s son with irreproachable proletarian credentials, turned fighter pilot, turned cosmonaut, would tour the world, meeting the heads of state of more than 30 countries – including the Queen and Fidel Castro – artists, writers, scientists and thousands of well-wishers. He was the human face of communist ideology – possibly the reason President John F Kennedy banned him from entering the US – and became a natural ambassador for both the space programme and the growing might and worldwide stature of his nation.

Read More:

His orbit of our planet in a flight lasting a mere 108 minutes on 12 April had ended with him bailing out of his spinning capsule, Vostok 1, after its hatch was blown open. He parachuted the last seven kilometres to Earth, something the Soviet Union kept quiet.

What they also kept quiet was the designer, engineer, strategist and all-round brains behind their project. Nearly every text detailing his life or the Soviet space programme refers to him as “shadowy”. By politburo decree, his full name was never spoken in public. Fearing the possibility of an assassination by their American rivals, his importance was such that his very existence was denied outside top Soviet political circles.

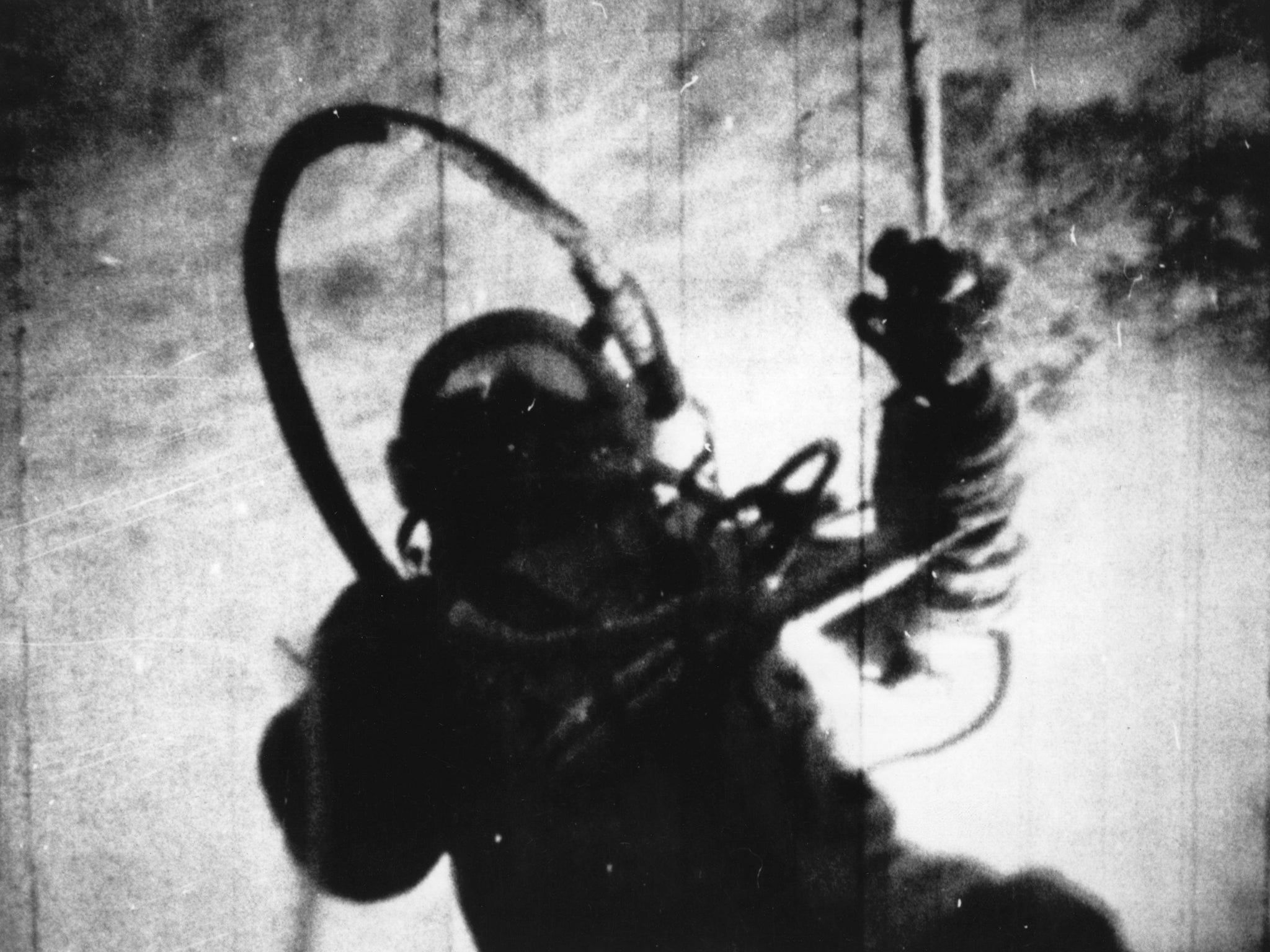

The cosmonauts who would fly in his spacecraft had no idea of his existence until they met him, and those who did only knew his initials. Alexei Leonov, the cosmonaut who would become the first human to walk in space, said: “We referred to him as ‘SP’. We did not know his full name. But there was no higher authority. Those around him treated him like a god.”

He also had a more illuminating moniker. In state broadcasts to the nation reporting the successes of the Soviet space programme he was called the “Chief Designer”. He was lauded, but the price was to become a non-person even in his own country. When the Nobel Prize committee asked if they could reward the man who made the first spaceflight possible, the Kremlin didn’t even reply, so keen were they to keep Korolev a secret.

Korolev was born in Ukraine in 1907, 10 years before the Russian revolution and 15 before Ukraine would be absorbed into the new state of the USSR. Yet it was those two events that would shape his life. He moved to Moscow to study aviation under Andrei Tupolev after whom the eponymous aircraft manufacturer is named, but by the early 1930s Korolev shifted focus, joining GIRD, the Soviet research bureau into rocketry, eventually becoming its director.

He was recruited to work under army marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was exploring the military potential of rockets and missiles in Leningrad (now St Petersburg). But Tukhachevsky would fall foul of autocratic Soviet leader Joseph Stalin whose growing paranoia led to him purging Soviet society of intellectuals. Between 1936 and 1938 Stalin’s Great Terror was an attempt to rid himself of people he feared might plot against him, especially those in the armed forces who had the means to foment insurrection.

Under Stalin, Korolev was beaten into admitting non-existent crimes of treason and sent to the Kolyma gold mine Gulag in Siberia. It was an effective death sentence

Tukhachevsky was shot on 12 June 1937 and his team, including Korolev, who was beaten into admitting non-existent crimes of treason, sent to the Kolyma gold mine Gulag in Siberia, following a trial lasting less than a minute. It was an effective death sentence.

The work was brutal. Food, water, clothing, sanitation and healthcare were significantly lacking and thousands died every month. Scurvy, dysentery and tuberculosis were rampant. Within five months Korolev had lost his teeth and his once healthy heart was failing. But he got lucky. It may not have seemed so at the time, but luck is a chameleon, coming in diverse and contrary forms. He had been pleading his innocence, writing appeals to the authorities and to Stalin himself – as did his wife – and, astonishingly, he was granted a retrial.

However, he was forced to trek to Moscow alone, a journey he later described to Leonov. “I walked out of prison into the snow. I traded my boots for a ride as far as Magadan where I needed to take a boat across the Okhotsk Sea to catch the train to Moscow. But I missed the last boat of the season…” However, fortune was on his side – the boat sank in a heavy storm.

Nonetheless, Korolev was stranded. “It was minus 40 degrees, I had nothing, and then I found a loaf of bread on a path. It was extraordinary. It is still a mystery how it got there.” He spent the rest of the winter eking out a living as a carpenter before setting off again. Yet en route his scurvy worsened and he collapsed. An old man at the railway station in Khabarovsk gave him herbs to chew on. “I believe it saved my life,” Korolev told Leonov. “There was enough vitamin C in the plants.”

It was more serendipitous luck. Missing the doomed ferry, finding the bread and being saved from scurvy; Korolev wasn’t especially religious, but became convinced his life had a purpose.

Although reconvicted at his Moscow trail, his sentence was reduced and he was directed to serve it in a sharashka, a penitentiary for intellectuals, scientists and engineers – essentially a labour camp where the inmates were assigned projects. Tupolev was, by now, also working in a sharashka and it was widely believed he had requested Korolev be transferred to work alongside him, hence the fortuitous recall to Moscow. Certainly Korolev credited him with his life. It was still prison, but a far cry from the Gulag.

Six years after his arrest, in June 1944, and with the Second World War turning in favour of the Soviet Union and its allies, Korolev was freed. He rarely spoke of his experiences – Leonov was the first to record them many years later – and he constantly lived in fear of being arrested again. In his otherwise spartan workspace – visitors had to stand, there was only one chair – he hanged a painting: Walking on Thin Ice, depicting Lenin trudging across a barely frozen Gulf of Finland. Its title was a constant reminder of how fragile his position in life was. In his book The Race, James Schefter wrote: “A new Sergei Korolev emerged. Maybe influenced by his experience as a prisoner he played the game of bureaucratic intrigue with increasing skill. He was a hard boss. He had been tested and survived. He would test those around him to the last days of his life.”

Korolev threw himself into the service of the state believing that if he proved his indispensability, it would protect him. And serve the state, to the point of fealty, is exactly what he did.

As the Second World War morphed into the Cold War, Stalin realised missile technology would provide him with both the means to defend the Soviet Union and threaten recalcitrant allies and opponents alike. The arms race between the eastern and western powers was underway. Suddenly Korolev’s professional credentials began to work in his favour. His previous “misdemeanours” were put aside and he was appointed head of missile and rocket design at the State Union Scientific Research Institute.

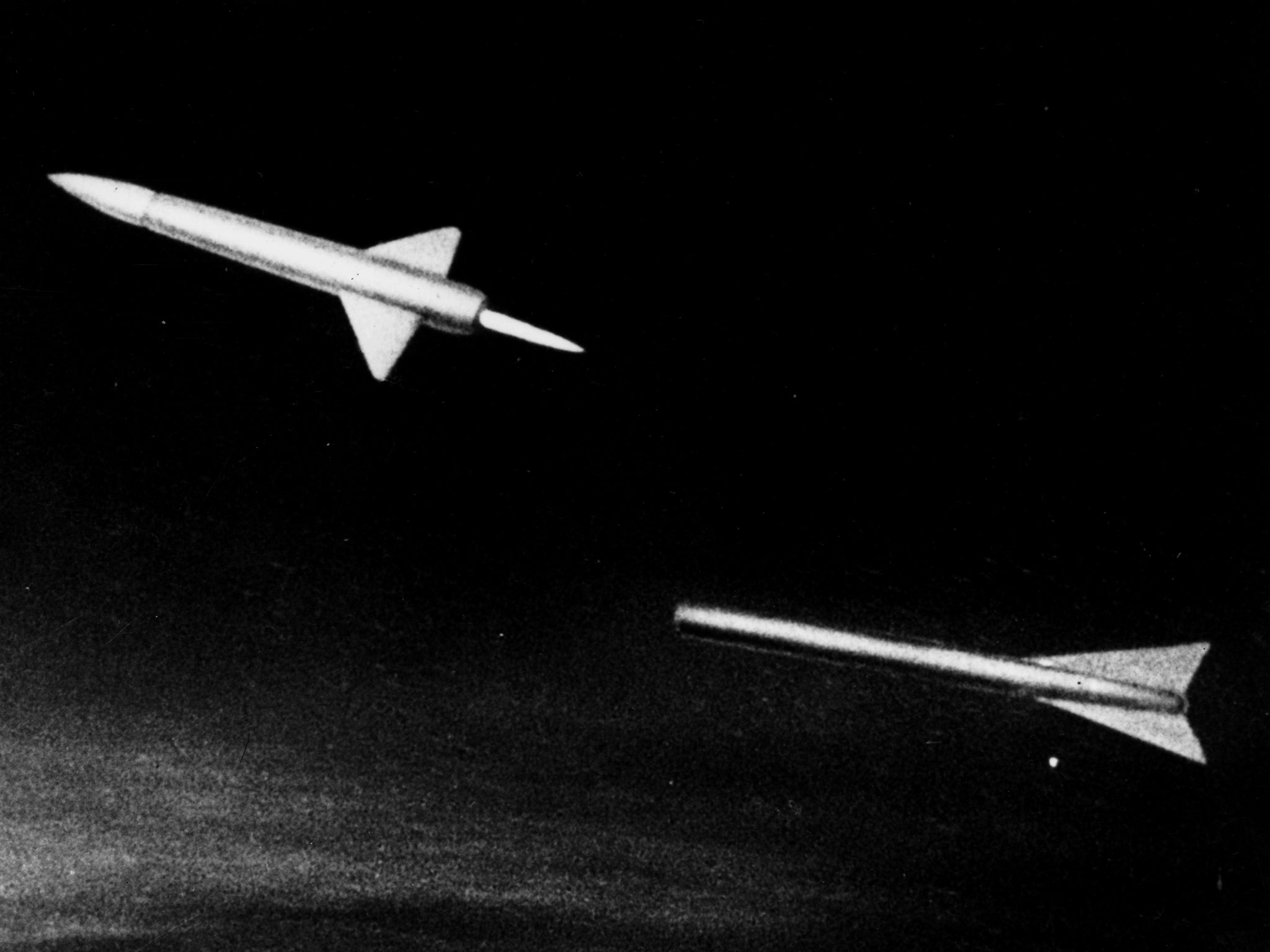

He began designing the R series of ballistic missiles, at first based on V-2 rockets captured from the Nazis after the war. Simultaneously, in the US, under the direction of Wernher von Braun, the former Nazi rocket specialist, identical work was underway. Von Braun’s political background was dubious but there was no doubting his engineering and organisational brilliance. The two sides were now locked in an arms and rocketry race, building up weapons capability but also their nations’ nascent space programmes. This, more than armaments, was to galvanise Korolev.

When the Soviet Union successfully launched the R-7, the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile on 21 August 1957, beating the Americans by 15 months, it was a result of Korolev’s assiduity and drive. It was noted. By now Stalin had been replaced by Nikita Khrushchev, who was attempting to undo some of the excesses of his despotic predecessor. Korolev was officially “rehabilitated” by the state, his previous “crimes” struck from the record as “unjust”. It was at this juncture that the authorities decided to suppress his identity, concerned their prize asset might be assassinated or, perhaps worse, abducted.

Three years after Korolev’s death, Americans were walking on the moon while the Soviets were blowing up rockets on their launchpads, an ignominious fall from grace

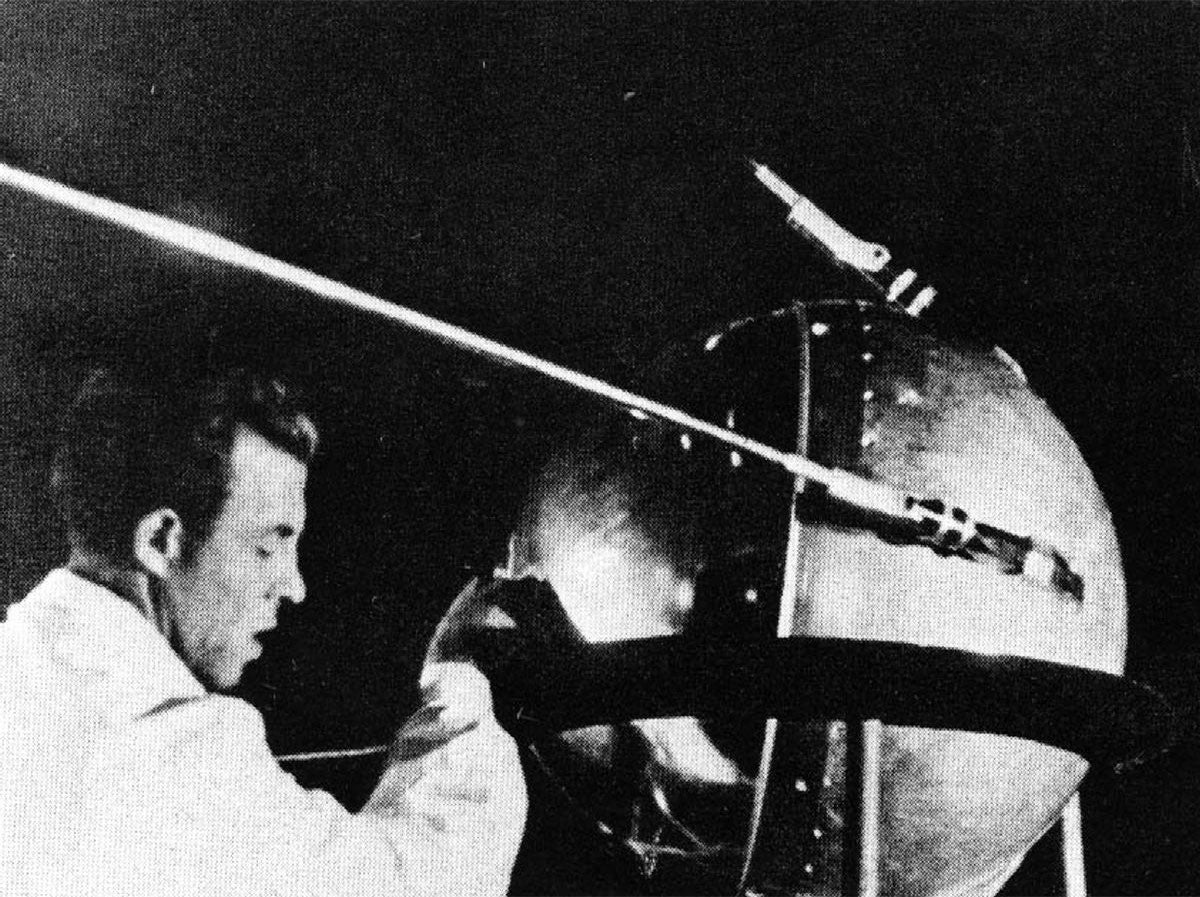

The R-7 was a two-stage rocket. Korolev had long-realised that multi-stage rockets were necessary if satellites or, indeed, humans were to enter space. By October he had adapted the design and stunned the world by launching Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit. The US was shocked – its beeping radio signal taunting and terrifying. Other nations were suddenly paying admiring attention to Soviet expertise. Khrushchev – until then rather bored by talk of space exploration – was now paying keen attention. Ballistic missiles could take a back seat: Korolev was authorised with putting a human into orbit at the earliest opportunity.

But who would that be? Korolev began his search for the first cosmonaut. Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin had been brought up on a farm collective in Smolensk. His family had fled German troops in October 1942 – Gagarin was beaten when he refused to work for the invaders and later sabotaged their tank batteries – and they survived the winter in a shelter they built themselves. Later he worked as a foundryman in Moscow before enrolling in flying school where he excelled and joined the military, piloting MiG-15 fighter jets in the Soviet Air Force. His credentials as an exemplary working-class Soviet patriot and citizen were impeccable, as was his timing.

He was 26 when Korolev first met him in 1960, part of a group of pilots selected by the Chief Designer for one reason: to fly in space. Korolev nicknamed them his “little eagles”. In his autobiography Two Sides of the Moon, co-written with US Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott, Leonov, also part of the early cosmonaut programme, writes of the first time the pilots met Korolev: “He strode into the room… and called on us to introduce ourselves and talk about our flying careers. When he came to Yuri Gagarin’s name he seemed to warm to him. Yuri turned red and got slightly flustered. Korolev seemed amused. He put aside his list, as if he had forgotten about the rest of us, and asked Yuri to talk about his childhood and career. After he left we gathered around Yuri. ‘You are the chosen one’,” I said.

Leonov was correct. Korolev had immediately contacted his cadre and the Kremlin. “This morning I met a handsome Russian man with lively blue eyes, sturdy and strong, an excellent pilot. He’s the man we should send into space first,” he told them.

It also helped that Gagarin was, at 157 centimetres, quite short. Korolev’s Vostok 1 space capsule was very cramped. In the end Gagarin’s only competition for the flight was the equally diminutive Gherman Titov, another exceptional candidate. But Titov had a bourgeois background – educated and the son of a teacher. And so Gagarin got the nod, a mere four days before the planned flight.

The night before launch Gagarin admitted to not sleeping a wink, although he pretended he had in case the watching doctors decided at the last minute to replace him with the well-rested Titov. Both men went to the launchpad, just in case. For Titov it must have been a difficult journey, but he wished his rival good luck as they clanged space helmets three times to recreate the Russian tradition of offering a departing friend three kisses.

Korolev was waiting. He had no time for such formalities or grandiose gestures. More scientist than showman he apparently kept looking at his watch. Gagarin, well hydrated, had kept him waiting by stopping his transport bus to urinate on its rear wheel, setting in vogue a cosmonaut tradition that only ceased in 2019 after spacesuits underwent a redesign.

Gagarin was promoted from senior lieutenant to major, strapped into Vostok 1 and told to wait. Korolev had deemed that countdowns to launches were an American affectation. When he and his team were ensconced in their bunker at 9.06am he simply pressed the ignition button. From his capsule they heard Gagarin shout “Poyekhali” (“Let’s go”) – 108 minutes later he had become the most celebrated human on Earth. And still nobody knew of Korolev.

There were to be more successes as the Americans scrambled to understand why they had been left behind. On 16 June 1963 Valentina Tereshkova would be the first woman to fly in space and Leonov would make the first extra-vehicular egress or “spacewalk” in March 1965. The next step would be to put a man on the moon and the Chief Designer was already preparing the rocket launcher – the 105-metre tall N-1 – to take them there. Only a month after and in direct response to Gagarin’s flight, Kennedy had committed the United States to landing a man on the moon before the decade was out. It seemed the race was on.

But in January 1966 complications developed during apparently routine surgery for an intestinal polyp – although reports vary – and Korolev died. Doctors attempting to control his breathing found his jaw had been so badly broken by Stalin’s interrogators that they could not insert a tube, and his treatment in the Gulag had weakened his heart.

His body was taken to the Hall of Columns in Moscow before being cremated and interred in the Kremlin wall. Gagarin gave the eulogy. Leonid Brezhnev, who had replaced Khrushchev as Soviet leader, said the nation had lost its “most outstanding son”. Korolev’s obituary appeared in Pravda, the first time his name appeared in the public domain and, at last, the world began to learn a little of the reputation of Sergei Pavlovich Korolev – three times a recipient of the Order of Lenin.

Even so, David Scott says that the first time he ever heard the Chief Designer’s full name mentioned in public wasn’t until 1975 on a visit to Russia. “Whether such an individual could exist in such secrecy today is open to question. And also the influence he wielded,” says Scott. “The old cosmonauts I have met insist it was his brilliance, drive and determination that drove them to excel.”

The most famous of those cosmonauts, Gagarin, would only survive Korolev by two years. He was killed in a flying accident in March 1968. Gagarin, the popular face of the Soviet space programme, and Korolev, its driving force and intellectual mentor, were gone.

The repercussions for the Soviet space programme were huge. The moon-landing project was taken over by Korolev’s deputy, Vasily Mishin, a competent enough engineer but, ultimately, lacking the ability, but mainly the resources, to develop the N-1 either technologically or politically. On 3 July 1969, in a desperate attempt to get Soviet lunar ambitions back on track and a mere 17 days before American Neil Armstrong would walk on the moon, a test launch of the N-1 turned into catastrophe. Moments after it left the launchpad, debris was seen falling from its base. It toppled. The resulting blast was regarded as the biggest non-nuclear explosion in history, yet the Soviet Union pretty much managed to keep it secret.

It made little difference. Three years after Korolev’s death, Americans were walking on the moon while the Soviets were blowing up rockets on their launchpads, an ignominious fall from grace. Mishin was fortunate Korolev was not there to witness it. “Had he lived,” said Leonov, “I believe Korolev would have rectified the N-1’s faults and kept us on schedule. I firmly believe we would have beaten the Americans [to the moon].” Leonov would almost certainly have been chosen to make the first moonwalk.

Others have a different opinion, stating that the N-1 would have had to be drastically modified or replaced. Doug Millard, senior space curator at London’s Science Museum, points out that “Korolev was working to demanding timescales without the financial strength of the US. Testing was limited. The first time the N-1’s engines were all fired together was on its first attempted flight with disastrous results. He might have solved the problems eventually but it would have taken time.” Even if he had been unsuccessful, Leonov believed only Korolev would have had the diplomatic wherewithal and confidence to tell Moscow – and likely receive its approval – that he was starting from scratch.

Korolev was constantly worried the Americans were ahead and Khrushchev was always wanting a bigger headline

Korolev was a remarkable combination of engineer, adminstrator and strategist. The Americans had the rocketry expertise of Von Braun and the political and impressarial renown of NASA’s lead administrator James Webb (whose biography was entitled The Man Who Ran the Moon), but Korolev was both rolled into one. “Both Korolev and von Braun were pretty even in technical ability,” says Millard. “Where Korolev scored was in managing Soviet political and design bureaux bureaucracy.

“Korolev was constantly worried the Americans were ahead and Khrushchev was always wanting a bigger headline,” says Millard. “It drove him on.” He was an obsessive worker, sleeping perhaps only six hours a night, and had a fearsome temper, but his passion never dimmed. And because Korolev had total oversight and the backing of the command economy of the Soviet Union he could call the shots. “This gave the Soviets a huge advantage in the early stages of the space race,” says Millard. “But it was insufficient to resource a moonshot. Meanwhile, the US was way behind at the start but constructed its own command economy by creating Nasa. It was supremely well-organised and better financed than the USSR. That eventually made the difference.”

But in the early years Korolev’s overarching management of politics and his teams meant he had the faculty to demand simple but effective strategies such as standardisation of components and equipment, creating hardware that could be transposed between spacecraft designs. This was key to the constant stream of successes the Soviets scored in the early 1960s, even though the technology, electronics and computers he was using were in many cases inferior to his American rivals. “What Korolev achieved was the absolute maximum with the resources he had,” says Millard admiringly. He was a keen innovator too – it was his simple but ingenious idea for spacecraft to slowly roll in flight so the sun would not just heat one side – expanding and possibly damaging it.

Korolev’s legacy is still felt today. His multipurpose Soyuz spacecraft design, which first flew in 1966, was so successful that in modified form it is still used in Russian space launches today and has made almost 150 crewed flights to date.

Some historians insist Korolev’s central role was overplayed by the Soviet authorities. Once dead they could tell his story, while those of his still-living cohorts had to remain a secret. Also internal divisions between Korolev and some of his contemporaries only became apparent long after – his rivalry with fellow designer Vladimir Chelomei dogged the programme for years. Korolev’s lack of co-operation with those with which he disagreed was a constant stumbling block. But it’s also true the Soviet space programme foundered once he was gone. His former tutor Tupolev described him as having “unlimited devotion to his ideas”.

Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony writing in Starman, a biography of Gagarin, tell the story of how, in 1961, journalist Olga Apenchenko had been allowed to meet the Chief Designer. Of course, she did not know his real name, but wrote that he was “a severe-looking man with massive features”. She described a noise she heard every time he entered a room: “A whisper of awe, respect, a mixture of both. When he entered a workshop everything changed – even the hum of the machines assumed a new overtone.” It is easy to imagine how, after his death, the dynamic, indeed the entire ethos of the programme, might have altered dramatically.

Although Korolev knew who had falsely incriminated him in 1938, he never told anybody. Leonov and others believed one accuser was another of Korolev’s bitter rivals, fellow engineer Valentin Glushko, who went on to design engines for the space programme. There was certainly lifelong animosity between the two, professionally and personally. Although Tukhachevsky’s team was all rounded up, Glushko only had a brief period of house arrest, arguably in return for denouncing Korolev and others.

Read More:

Ironically, it would be Glushko who brought about the de facto end to the Korolev era. He was eventually promoted to lead the Soviet space programme after Mishin was fired in 1973. One of his first decisions was to cancel the Korolev-inspired moon-landing programme. Glushko lacked the nous and technical acumen of his former rival and, to be fair, he was denied the resources too. He died in 1989 with many of his aims unfulfilled.

Korolev was a man who had the ear of those at the very top, especially Khrushchev, while others did not. He tenure was one of vision and enthusiasm – a man who almost single-handedly turned the once agrarian Soviet Union into an innovative leader, repeatedly humiliating the more technologically advanced US. And without him, 60 years ago, Yuri Gagarin would never have become the most famous person on earth. It was a pity he had to die before the world had any inkling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks