Is this the end of the line for the King’s Cross Badlands?

A flurry of planning applications threatens to change King’s Cross forever. Owen Ward delves into the area’s long history and explores why new development trends could destroy one of London’s most precious areas

What does King’s Cross mean to you? Most people will likely think of its station, immortalised by the Harry Potter novels and the magical platform nine-and-three-quarters. To investors and developers, it’s now a hipster shopping centre, an edgy luxury estate and an international business centre. But to those who really know the place, live here and drive and walk its streets, it’s a grimy and industrial – but strangely beautiful – area, still firmly grounded in its Victorian past, and still the first home of London’s working class.

To those who observe carefully, King’s Cross has character, personality and moods, even – it is more like a person than a place. Born almost two centuries ago, it has seen London grow and rise around it, given a home to hundreds of thousands of Londoners, and now, tired and old, resigns itself to telling those who will listen the stories of its long past.

I have walked almost every street in central London. I keep a map on my wall and colour the streets that I’ve walked upon. I’ve seen all of Bloomsbury, Covent Garden, Marylebone, Westminster, Soho and the City. I am fascinated by London’s built environment and the stories it has to tell, to those who will seek them out. Sometimes people ask me where my favourite place in London is, to which I reply without hesitation: the Badlands of King’s Cross.

Much of the distinctive authenticity and griminess of King’s Cross has been eroded and erased in recent years. North of Euston Road, where gasholders once rose and fell, and where children would steal great lumps of coal to heat their homes, the essential character of this place is lost forever. All that remains of the cylinders is a shell surrounding luxury apartment blocks, £7m apiece, a mere decorative touch. Overpriced and irrelevant shops fill the arcades where coal was once shovelled. Only a thin veneer of King’s Cross really remains, covering the weakness of a chipboard of gentrification, in a discordant and uncomfortable juxtaposition. True, it is far better that some of King’s Cross really remains than none at all – but it is a boutique kind of conservation – something fitting to a barn conversion, rather than the powerhouse of the former “capital of the world”.

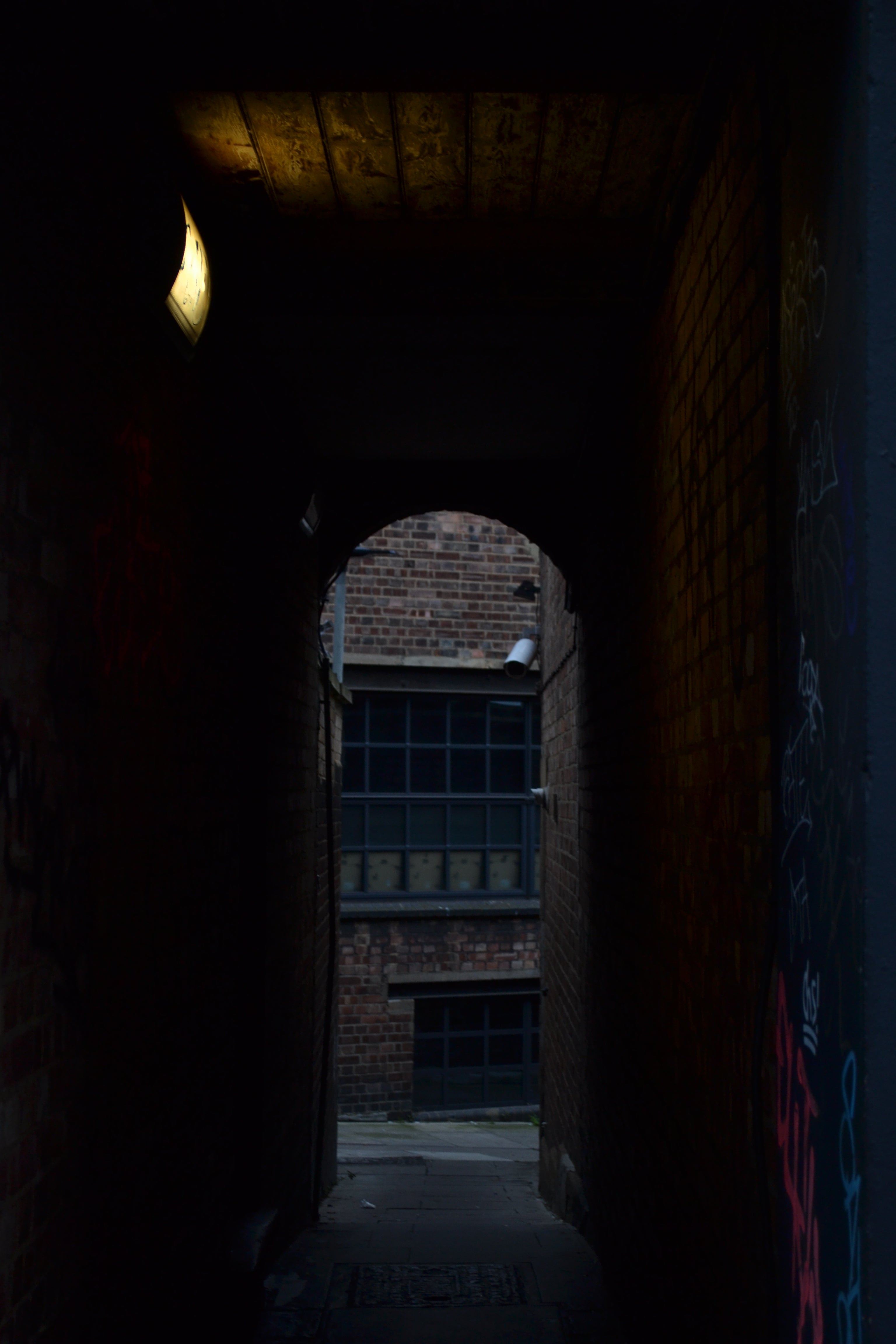

But King’s Cross does not extend only to the north of Euston Road. The beating heart of King’s Cross, the only place that still retains that distinctive King’s Cross character, survives along the backstreets of what I call its badlands, a place where almost nobody visits, and where alleys are so thin, dark and dirty that nobody would walk those paths – unless, like me, they were seeking out London’s stories.

Comprising a number of east-west streets connecting Gray’s Inn Road to King’s Cross Road, two major thoroughfares, one would logically expect a great deal of traffic, vehicular or pedestrian, to circulate these streets. But strangely, they are always empty and bleak. Walking here, one feels as though almost nothing has been changed for a century or more.

The entire area is in a remarkable state of preservation. Small details, signage and street environment features not seen anywhere else in London punctuate the unbroken rhythm of London stock brick and sash windows.

While plenty of areas of London have been “conserved” to this standard, or better, they have done so in a fundamentally different way. Most have undergone a process of urban evolution throughout the 20th century, following a natural trend towards a change in appearance, use and character. Then when concerns are raised about this trend of change, efforts are made to sensitively “restore” a place to its “former glory”.

The problem with this is that nobody really can be sure of what a place once was. We all come to an overly optimistic, perfected and glamorous view of what Victorian Fitzrovia or Georgian Bloomsbury was like. We keep and exaggerate the best parts in our mental image, and erase everything that was undesirable about it. Nobody talks about the fact that before Bloomsbury was even completed in 1840, entire mews streets had been taken over by homeless and diseased populations. And yet today we think of Bloomsbury’s mews streets as being some of its most well-preserved and authentic places. Nobody would seek to encourage those streets to return to their dubious past. We make a necessarily imbalanced and inaccurate effort at retrospective conservation. We conserve what we like and destroy what we don’t.

The Badlands of King’s Cross are fundamentally different. Nobody has attempted to restore it to some caricatured version of its past. The natural urban evolution of this place has not been to change and modernise, but simply to remain unchanged, untouched. This place is well-preserved not because someone has made an effort to preserve it, but simply because nobody has made any effort to change it. It has undergone a process of organic conservation, where despite the winds of change blowing strongly all around, somehow, this area has remained in the eye of the storm – calm, empty and bleak, for almost 200 years.

But how could King’s Cross be any different? After all, this is exactly its personality: an authentic, real, place. This is why so many unique and strange artefacts from a bygone age remain untouched, when almost everywhere else they have been damaged or removed. King’s Cross doesn’t want to change. It wants to stay the same, to continue as London’s home of the working class, and to continue telling its story to those who will seek it out.

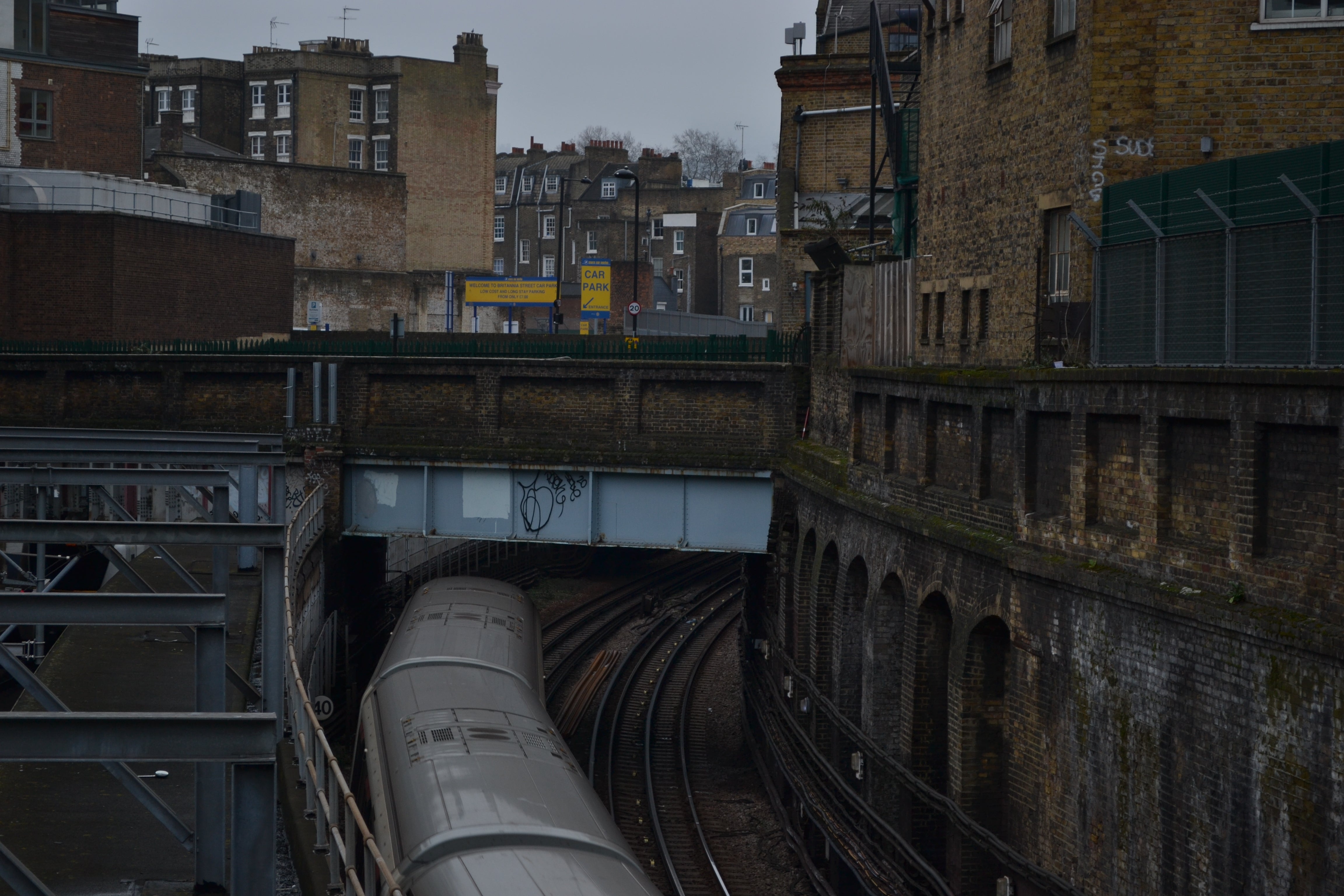

One of the most unique aspects of this area’s urban form comprises the railway line that cuts straight through it. Constructed using the famed “cut-and-cover” method, the Victorians cut a wide trench through this area in the 1800s for the Metropolitan railway line, the first underground railway in the world. Just as the name suggests, in most places once the railway trench was cut, it was covered, and built over. But here, this never happened. An urban canyon was cut through these badlands and never built over, or even covered at all. It is evidence of a revolutionary moment in the world’s history, frozen for almost two centuries for all to see. Nobody tried to conserve this, to prevent this land being built over. Somehow, it just happened. King’s Cross kept it for those who wish to seek it out.

The streets of the badlands criss-cross the railway with old, weakened bridges, some not even strong enough for vehicles. Essentially all of the walls are just about too tall to be peered over – and indeed, just walking these streets, you won’t catch a glimpse of the railway at all – only hear the rumbling of the trains beneath you. It is almost as though King’s Cross doesn’t want it to be a cheap view, that anyone can come and see. You have to seek it out, sit on walls, venture into car parks, and clamber onto ledges to get a view of it at all.

But when you do find one of the handful of spots where the railway can be seen, you are well rewarded. The gentle curve of the railway affords long views north and south, so that you can see as far north as to King’s Cross station itself, and in some places, as far south as Farringdon.

Rising along the edge of the urban canyon are numerous bizarre structures and odd buildings. Georgian terraces that have been seemingly sliced in half, with small windows peering out onto the railway. Empty, abandoned plots of land, and dilapidated chimneys. Long-abandoned platforms, no longer accessible from King’s Cross, can be seen dotted with vintage advertisement posters. It is a place truly frozen in time – and not because anyone is making any effort whatsoever to conserve it, but because somehow, nobody has made any effort to change it at all. It is authentic, a living museum of London’s past, with many strange stories yet to tell.

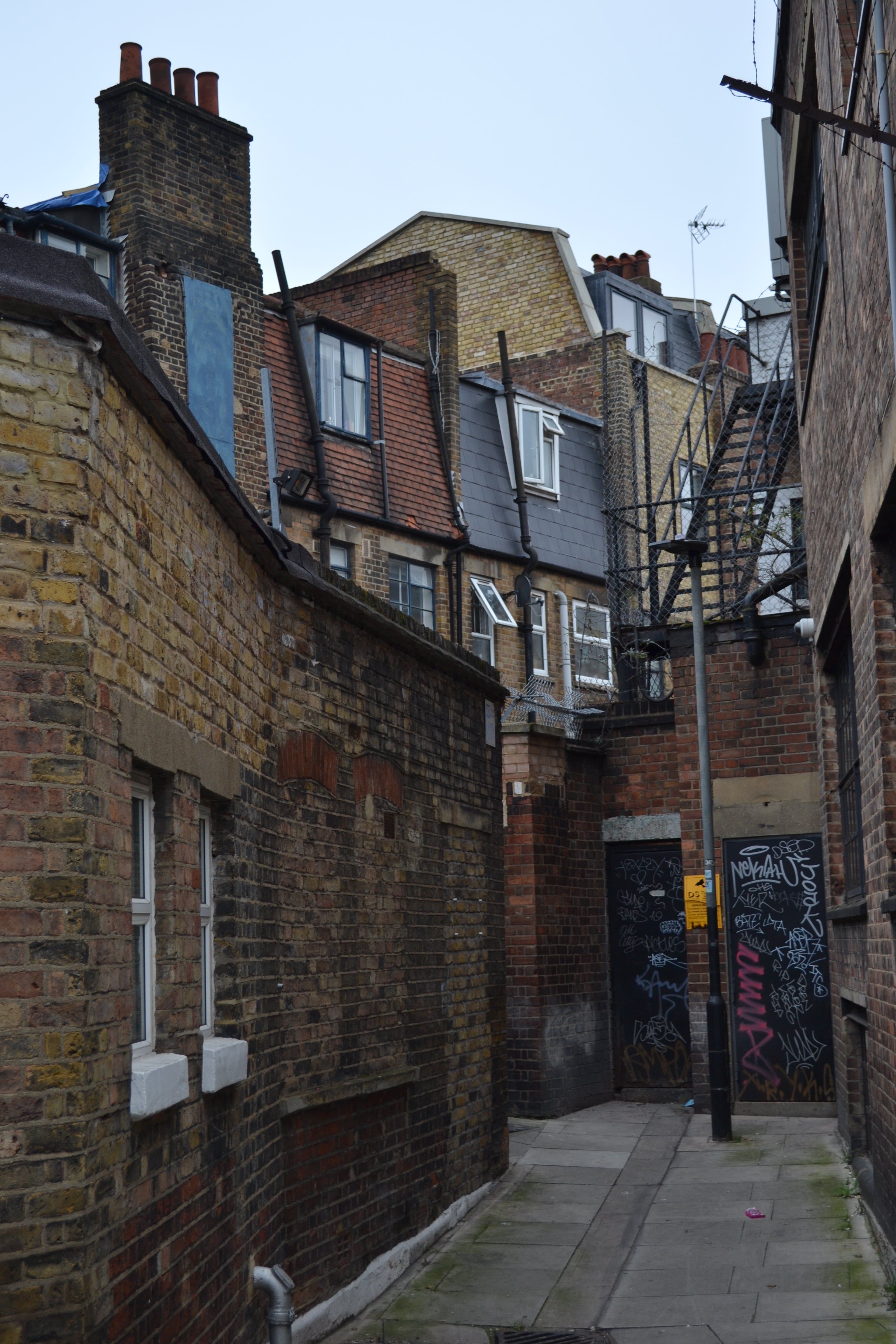

One thing that strikes me when walking these streets is the remarkable uniformity of architectural form and materials. Almost everything is constructed in London stock brick, and anything that isn’t has been coated with such an excess of industrial grime that it appears similarly dull, and old. Just like a canyon, or badlands, it seems like the entire area has been carved out of a single enormous block of stone, weathered and eroded by the acidic atmosphere of Victorian London.

One thing I love about this area is that it isn’t perfect by any means, and nobody is trying to make it perfect – it’s dirty, dilapidated and vandalised in places. But all of it is organic and authentic, and somehow still civilised.

Look at the above photo. It’s an old place, it’s been changed incrementally, some might even say inappropriately, but it is all domestic, and homely, somehow. There’s graffiti, but only on the wooden panels blocking up the doors. It’s a respectful and civilised kind of criminality. Not one vandal has ventured to spray the walls, instead following an unspoken rule to vandalise only that which is deserving of vandalism. The built environment demands respect, and even vandals pay those respects. It inspires a civilised and authentic kind of criminality.

For those who know the social history of King’s Cross, this respectful criminality is also a clear survivor of its long and often dubious past. One of the most striking accounts of working class King’s Cross describes a story, circa 1930, where the Metropolitan Police were searching for a pair of criminals from further north in Islington. These criminals had ventured into King’s Cross, abducted a young woman, and raped her. The working class of King’s Cross were so outraged at this terrible crime that they consulted with local gangs and successfully tracked down the two criminals. They then proceeded to abduct the criminals, castrate them, and dump them on the steps of the Judd Street police station. Horrendous and vicious, yet only motivated by the need to serve a primal sort of justice, to attack those deserving of attack. The police station took no further action.

It seems like another world, almost medieval, where such things could play out. Yet it was less than a hundred years ago, and one of the individuals party to the events is remarkably still alive today. King’s Cross lives on, and still tells its stories to those who will listen.

Yet all it takes to break this perfect imperfection is a single error. One building too tall, too bright, too modern, and the entire impression is shattered. The incredible uniformity of this place and the unique three-dimensional nature of the urban form creates an environment where a single building could singularly wreck views in all directions. And once a new precedent is set, and a new direction is taken in the urban evolution of this place, it is surely inevitable that the entire impression will slowly disintegrate. And then, perhaps, we will finally see The End of King’s Cross.

The Royal Nose Throat and Ear Hospital on Gray’s Inn Road has recently been vacated to another site in Bloomsbury. As a result, it has lain empty and bleak, while investors have sought for a way to redevelop this site and bring it back into use.

The site is large, sitting within the badlands, and is home to a great number of unique features and buildings forming a substantial contribution to the character of King’s Cross. Simply losing these features would be a tragedy in itself. But the greatest risk in all redevelopment schemes is that the push for greater profit, for the new and the shiny, so alien to this area, will destroy not only this site’s importance, but the entire character and impression of this place and King’s Cross as a whole.

When this site came up for redevelopment in Camden’s Site Allocation Brief, my conservation committee made an especial effort to suggest policies that would ensure development not only preserved the importance of this site, but actually further revealed and enhanced the area’s special history. I suggested that a walking route could be opened up along the urban canyon, allowing those walking in the area to come and see it for themselves, and the gloriously industrial views north and south along the railway lines.

And yet, so typically of planning in London, a scheme has come forward which is unfortunately uneducated as to the area’s architecture and character.

Perhaps the towers are not so ugly as most proposed in Camden. But its design offers such a stark contrast to the uniformity and domesticity of the entirety of the surrounding area, and its size would cause it to be seen from views all throughout the badlands. Perched right on the edge of the urban canyon, it could forever change the character of this unique feature.

It seems to me to almost be a stranger in a foreign land, who while visiting a tourist attraction, becomes lost and finds themselves in a dark and dirty back alley. Awkward and alien to the culture of the land, it stands proud, yet can keenly feel suspicious eyes upon it. It attempts to communicate with those around it, but cannot speak the language, and stutters out incoherent sounds and words to the bemusement of all.

Or perhaps it is more like a child at school, who forgets that it’s non-uniform day, and feels a sense of shock and embarrassment as the strange diversity yet domestic uniformity of home-clothed children offer a bleak contrast to the formal, polished, uniformed child.

Seen from the remarkable Wicklow Street, it is particularly impertinent. Not only rising far taller than the neighbouring domestic buildings, which look stubbornly on, it makes such little effort to integrate itself with the modesty and culture of the area. Truly, it is an alien to King’s Cross.

While sensitive and unique features, so integral to the character and personality of this area, would simply be demolished.

Seeing these images, and looking through the application documents, I surprisingly don’t feel angry at the prospect of such incredible change – only disappointed. Almost all architects research the context of their site, and make some effort to integrate their design with the historic environment. It is clear to me that the architects simply do not know King’s Cross, or what makes it special. They did not truly seek out its personality, nor its stories, and consequently could not find them nor learn from them. Being such an old and reserved character, King’s Cross cannot be understood in a day – you have to win its trust, and learn little by little its story and past. The architecture does not speak to me of disrespect, but of naivety and confusion – just like the child who turns up in uniform, or a tourist lost on a dangerous back alley.

All developments are an opportunity to build something special – to create something that everyone can love and appreciate, for generations or even centuries to come. Good architecture is simultaneously something useful, profitable and a work of public art. The wealth of opportunity that a place like King’s Cross brings for outstanding architecture is enormous – unlimited, even. But to create something that lasts for centuries, it must take great effort to truly understand the foundations of the place, what it needs, and what it wants.

London is a city that has lived for 2,000 years. In deciding its future, we should not look only to the present, but to its long history. Change should aspire to be permanent. Good buildings, like King’s Cross and St Pancras stations, will never be demolished. They have become permanent features of the environment, through their utility, beauty and worldwide love of their architecture.

Yet this development bears no mark of King’s Cross or London upon it whatsoever. It could easily be from any city, in any country, throughout the world. Entirely undistinguished, it is simply a missed opportunity.

But perhaps it is inevitable. What makes the Badlands of King’s Cross so remarkable is that nobody has attempted to preserve them. Nobody has curated this area, very few were prepared to defend its heritage, because up until this point, the natural evolution of this place has been to not evolve at all. Now it seems times are changing. Already a tower has been approved further down Gray’s Inn Road, another tower applied for opposite King’s Cross station itself, and another great block applied for just to the south of this site. It seems as though time is finally catching up with King’s Cross, and its delicate state of preservation could soon be shattered.

But inevitable change does not mean that that change is inevitably ignorant and naive. Whatever happens to King’s Cross, evolutions in its environment should be firmly rooted in its past, its urban fabric. Change does not need to mean a reversion, or upset. It is an opportunity for real enhancement. To achieve this, one must really understand what King’s Cross is about, its personality, what it means. We have the tools and power to ensure that investors do this, to make sure that they really know King’s Cross, without sacrificing profit or opportunity. The question for me is whether we have the courage to do this.

It is up to Camden now, to decide the future of this area, and what King’s Cross will mean for generations to come. The world’s first home to the working class, uniquely and remarkably preserved – or a modern, shiny and entirely undistinguished collection of office blocks and hotels? Whatever happens, King’s Cross cannot be departed with lightly. In the modern age, its remarkable character will be forever lost once damaged. To me that makes King’s Cross more precious than anything in the world. To others, land of any kind is simply an investment opportunity, and its heritage an inconvenient buzzword.

What does King’s Cross mean to Camden? It certainly exceeded itself in preserving the appearance of the lands to the north, now home to its own offices. But will the more domestic, modest and authentic badlands warrant such careful investment? We will find out for ourselves in the coming months, as its planners and councillors decide whether to approve or refuse these applications, and whether to heed my own and my committee’s advice in protecting the special heritage of King’s Cross.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks