Henry II was luckier than his successors when it came to getting away with murder

Patrick Cockburn reflects on state assassinations past and present and is immediately struck by the comparisons between the death of Thomas Becket and the even more grisly fate of Jamal Khashoggi

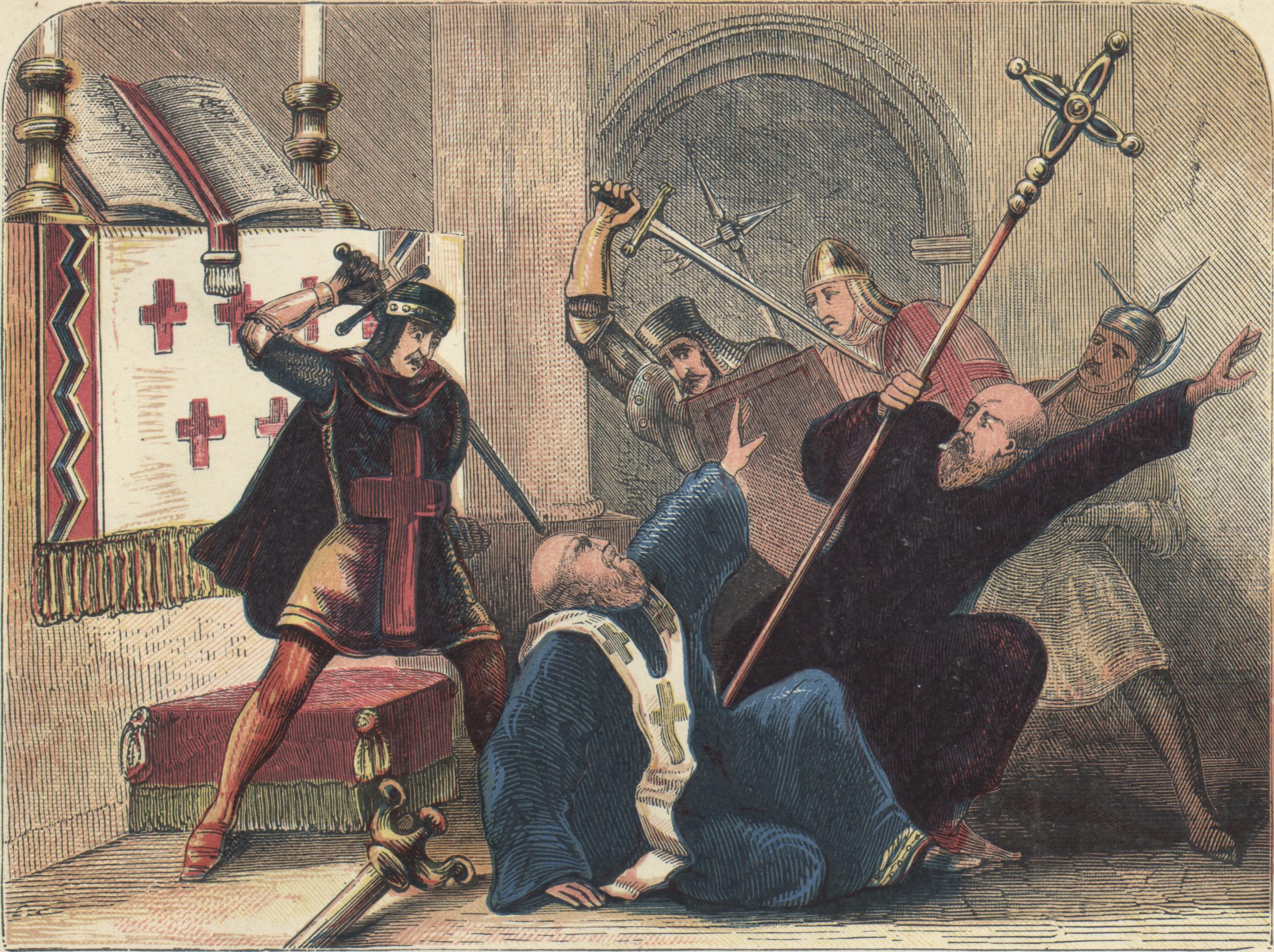

I look through the window of my house in Canterbury at the medieval church of St Dunstan’s, 40 yards away on the other side of the road. This makes me think about the murder of the Archbishop, Thomas Becket, by four knights of Henry II in Canterbury on 29 December 1170 – the 850th anniversary of which is this year. The king admitted later that his furious tirades directed at his retainers for not having done anything by way of revenge against Becket, his former protege tuned bitter opponent, had inspired the killers to commit the crime, but he adamantly denied that he had personally ordered the assassination.

The link between the death of Becket – certainly the most famous political murder in English history – and St Dunstan’s is simple: it was from this church on the outskirts of medieval Canterbury that three-and-a-half years later, on 12 July 1174, a barefoot Henry, the formidable founder of the Plantaganet dynasty known for his fierce personal pride, dressed in a hairshirt worn beneath a smock, began his penitential walk towards Canterbury Cathedral, half a mile away inside the city walls.

The king walked down what is now St Dunstan’s Street through West Gate, a gateway today flanked by two huge medieval towers built 200 years after Henry passed this way. It would be interesting to know more about how the people of Canterbury reacted to the sight of a much-feared monarch, ruler of an empire that included all of England and half of France, as he endured self-inflicted ritual humiliation before their eyes.

Once inside the cathedral, his display of penitence became even more abject and pronounced as he went down the steps into the ancient Norman crypt and knelt before the tomb where Becket had been hastily buried. He confessed that it had been his “incautious words” that had ignited a train of events that culminated in the killing and asked that he be punished for his crime.

The assembled clergy swiftly granted his wish and beat him with rods, probably consisting of elm or birch saplings tied together. The bishops were each allowed to strike him five times, and the 80 or more monks three times, suggesting that they cannot have hit him very hard since he survived the flagellation without serious injury. But the purpose of the public scourging of the king was primarily symbolic and, for the rest of day and through the night, Henry prayed and fasted beside the tomb, seeking forgiveness for the murder of a man who was already regarded across Europe as a martyr who had died in defence of his church and faith.

If Henry was expecting to see signs of divine approval of such a spectacular penance, he did not have long to wait. His barefoot walk and public scourging had taken place at a bad moment for him when part of his own family, including his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine and his elder sons, had risen against him in what was known as The Great Revolt. At the same time, King William I of Scotland, “William the Lion”, invaded northern England in support of the rebels.

It was probably because his fortunes were at such a low ebb that Henry had felt compelled to try to restore his reputation through a highly visible demonstration of penitence in Canterbury. Evidence that God was now decisively on his side came with astonishingly speed: on 13 July 1174, the day after Henry had been beaten by the bishops and monks, a small English force surprised the Scottish king in the mist at Alnwick in Northumberland and captured him. Other victories quickly followed, leading to the collapse of the rebellions in England and France, making Henry secure on his throne and more powerful than ever.

But this was not the only benefit Henry drew from so dramatically taking the blame for Becket’s death. Miraculous cures of the sick and disabled multiplied among those who prayed close to where Becket was buried or drank water supposedly containing drops of his blood. These were reported within days of his murder: never very popular in life, he rapidly became the revered centre of a cult and his resting place was soon the premier destination for pilgrimages in England. The movement was spontaneous and caught the monks by surprise: six days after the assassination, a blind woman named Britheva said that her sight had been restored by applying blood-stained rags to her eyes.

It was through the artful manipulation of public opinion by his melodramatic acts of penitence and repeated declarations of over-whelming grief, that Henry was able to achieve exoneration

Soon after, a dumb man called William, who spent the night beside Becket’s tomb, was not cured on the spot but recovered the power of speech on his return to London. In the coming years, a vast variety of miracles followed: the mad became sane, cripples threw away their crutches, and whole villages recovered from the plague. The cult of St Thomas – a martyr who had died defending his faith and the rights of the church over mighty authority – spread through Europe, his semi-divine status universally acknowledged until the Reformation 350 years later, when his magnificent shrine in the cathedral – his body had been transferred there from the tomb in the crypt – was looted and demolished.

The sanctification of Becket might have been highly damaging to Henry, as he was undoubtedly the man who, intentionally or not, had played a crucial role in precipitating the murder. Moreover, his complicity at the time and subsequent regret over what had happened was dubious. It was through the artful manipulation of public opinion by his melodramatic acts of penitence and repeated declarations of over-whelming grief, that Henry was able to achieve exoneration.

More astonishing, he deftly if hypocritically – for it was never clear just how much he regretted Becket being dead – was able to turn England’s most notorious assassination to his political advantage. He brazenly inserted himself into the new cult of St Thomas (Becket was sanctified in 1173) by his public displays of remorse. Criminals were once supposed to return the scene of their crime, but few have done so as frequently, or with such benefit to themselves, as Henry was to do. Until he died in 1189, he kept returning to Canterbury to re-stage his first successful pilgrimage. Over 15 years, he made nine or 10 more pilgrimages to Becket’s tomb, often bringing with him royal visitors, such as King Louis of France.

I have always been intrigued by the skill with which Henry coopted the cult that grew up around the murdered Becket and contrived to make his role in the martyrdom a prop for his rule.

Most political leaders accused of high crimes, be they monarchs or dictators, presidents or prime ministers, stick to a firm denial of responsibility when accused of crimes. Henry II was one of several English medieval kings to face the problem of how to explain away the murder of an enemy or a rival.

“They love not poison that do poison need,” says Shakespeare’s Henry Bolingbroke, who soon afterwards became Henry IV, when he was shown the body of his murdered predecessor Richard II by his reward-seeking assassin. “Though I did wish him dead, I hate the murderer, love him murdered,” he says ungratefully when reminded that it was he who had given the order for the deed.

Henry II was a better politician or maybe just luckier than his successors on the English throne when it came to getting away with murder. What did he really feel about the killing? He had showed almost hysterical regret when he heard the news in France about the assassination, putting on sackcloth and ashes and retiring to his bedroom for three days. But his regrets may have had more to do with the likely political consequences of a disastrous mistake that could have permanently besmirch his reputation.

The murder of Becket and Henry II’s role in it was one of the great set pieces of English history, the melodramatic culmination of a quarrel between Becket and the king, and between church and state

At first, he made a determined effort to blame Becket for having brought his death on himself through his provocative actions. Henry made no serious effort to punish the four knights who had carried out the killing in the belief that they were eliminating a traitor to the crown. He never appears to have forgiven Becket for what he saw as his treacherous change of sides after Henry had promoted him to be chancellor of England and then Archbishop of Canterbury in order to enforce the king’s authority over the church.

This year is the 850th anniversary of the death of Becket and celebrations of his martyrdom had been planned that are now likely to be marginalised or abandoned in the great panic over Covid-19. The streets down which Henry II walked barefoot, presumably watched by crowds of amazed townspeople, are today empty and religious services in the cathedral have been suspended. This is a pity because the murder of Becket and Henry II’s role in it was once one of the great set pieces of English history, the melodramatic culmination of a quarrel between Becket and the king, which was also a confrontation between church and state.

The question supposedly asked by Henry, which sent the death squad of four knights riding furiously towards Canterbury – “who will rid me of this turbulent priest?” – was a fake fact, an invention by an 18th-century historian. Yet better attested quotes from Henry cited by contemporary eyewitnesses carry a similar menacing message, though the exact words may differ. Gervase of Canterbury, for instance, says that Henry angrily asked his entourage: “How many cowardly useless drones have I nourished that not even a single one is willing to avenge me of my wrongs?” Other sources quote Henry as dwelling on Becket’s lowly origins and his rage that his former protege should have ungratefully defied him.

Had Henry not had his back to the wall during the Great Revolt of 1174, he might not have taken the risk of opening admitting his guilt and accepting ritual punishment and humiliation. Political leaders down the centuries have usually decided that the best strategy when accused of a crime is to stick to a firm denial.

This is a sensible approach since their accusers may strongly suspect, but cannot prove, their complicity in some spectacular piece of wrongdoing. Very occasionally, this strategy can blow up in the face of an accused leader, as happened to President Nixon during the Watergate scandal, when tape recordings emerged that proved false his denial that he knew what was going on. Luckily for them, medieval monarchs with blood on their hands did not have to face this problem. Other leaders down the ages, Saddam Hussein being a prime example of this, were political gangsters who did not bother to conceal their murders because their use of extreme violence was geared to intimidate and deter their numerous enemies.

I have thought a lot over the past 18 months about the murder of Becket and Henry’s surprisingly successful bid to escape blame and turn it to his advantage. I had always been interested in this drama because so many of its key moments 850 years ago happened in Canterbury on my doorstep or within sight of where I live.

But it was when the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered and dismembered by Saudi security men in Istanbul on 2 October 2018 that I began to think about the similarities and differences between state-ordered assassinations past and present. I had been immediately struck by the analogies with the death of Becket and the even more grisly fate of Khashoggi. Both men had their faults but had died for a cause. In both cases, the murder of the victim was a terrible mistake from the point of view of the perpetrators because they converted a living opponent, whose power to damage them was limited, into a dead martyr whose fate would permanently haunt them.

The Saudi authorities showed considerably less skill than the Plantagenets in coping with the aftermath of the crime: after first denying having anything to do with it, they finally accepted involvement, but denied that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, had ordered the killing. He himself, likewise, denies doing so, while accepting overall responsibility for it “because it happened on my watch”. The CIA, basing their opinion on multiple sources of intelligence, said with “high confidence” that the crown prince must have given orders for Khashoggi to be killed. Ever since, the Saudi authorities have desperately tried to distance themselves from the assassination, but with nothing like the skill or success of Henry II.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

34Comments