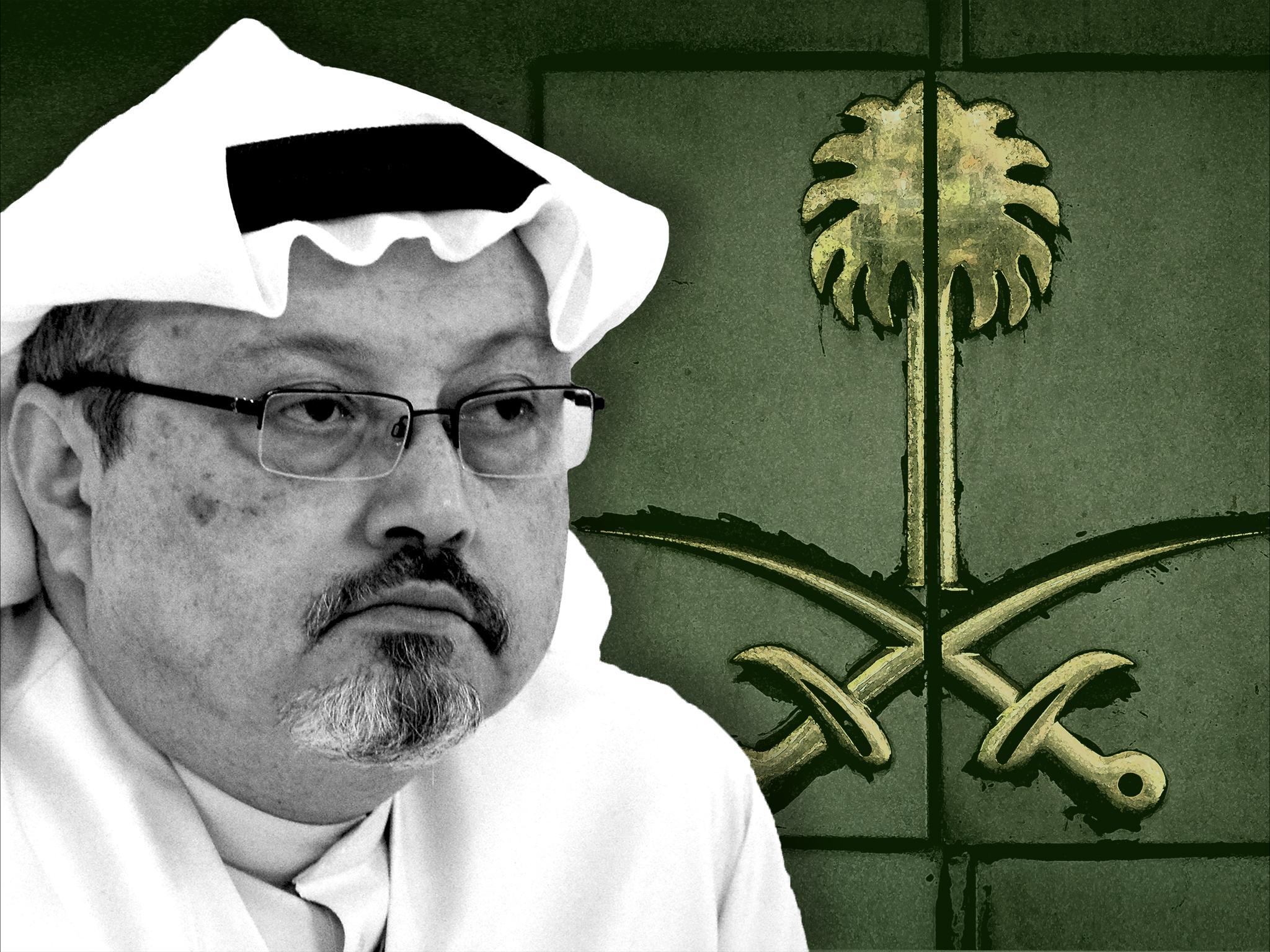

Jamal Khashoggi murder: More than a year on, there’s still much to learn

The publication of Jonathan Rugman’s ‘The Killing in the Consulate’ sheds light on the journalist’s brutal end. Kim Sengupta considers an event that shocked the world

The death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic.” The saying, attributed to Joseph Stalin, is in Jonathan Rugman’s fine book about Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi journalist seized, murdered and dismembered at his country’s consulate in Istanbul.

The Saudi government, unlike Stalin’s Russia, is not accused of liquidating millions, although the airstrikes it has carried out in Yemen has led to thousands being killed. At home the kingdom has executed around 700 people, by beheading with the corpses sometime crucified, in the past six years.

The appalling carnage of Yemen has been well charted in the international media, but there has been little coverage of the miscarriages of justice among those put to death by the state. The killing of Khashoggi, however, has led to massive coverage resulting in international shock, putting the brutality of some in the kingdom’s hierarchy under an uncomfortable spotlight.

The intense coverage by journalists of Khashoggi’s murder was mainly due to the fact that he was one of our own, and some of us writing about it had known him over the years.

I had met Jamal on a few occasions when he was an official at the Saudi embassy in London in the early 2000s. This was soon after 9/11, with news emerging of Saudi involvement in the attacks, an awkward time for Khashoggi to be at his post. In 2002, a year before taking the job, he had written a newspaper article headlined “A Saudi mea culpa”, condemning the extremist religious ideology which had motivated the hijackers.

But it was also the time of the Iraq war and Khashoggi could counter the accusations over the Twin Towers with the duplicity of Bush and Blair in concocting the excuse for the invasion which was to have disastrous consequences.

I spent a fair amount of time in Afghanistan and Iraq during that period, and chatting to Khashoggi about these countries gave me an interesting insight into his colourful, complex and contradictory life.

In the 1990s Khashoggi was a member of the radical Muslim Brotherhood. He had gone to cover the Afghan war as journalist at the invitation of Osama bin Laden and interviewed the future leader of al-Qaeda several times. There are photographs of him holding a rocket-propelled grenade launcher in his hands, proudly posing alongside a group of Saudi jihadis.

Khashoggi’s activities at that time were used to smear him as an extremist and terrorist sympathiser by a few people, including journalists, after his murder. The accusations were false and spiteful: his views had changed drastically over the years, something which could be plainly be seen in his writing and publicly expressed views.

Change, or perceived change, is a running theme in the life of Jamal Khashoggi

Change, or perceived change, is a running theme in the life of Jamal Khashoggi. After Afghanistan there were those who claimed that he had become a Saudi intelligence agent and informer. No evidence had been produced, however, to back that up.

In 2003 Khashoggi was fired as editor of Al Watan newspaper for an article criticising intolerant obscurantist dogma. The paper was owned by Prince Bandar bin Khalid al-Faisal. Khashoggi was rescued from unemployment by Prince Turki al-Faisal, the veteran head of the Saudi intelligence service – an example of the tangled relationship in the kingdom’s ruling order and Khashoggi’s path through it.

Prince Turki took Khashoggi to London when he became ambassador here and then to Washington when he subsequently got the same job there. Khashoggi followed the prince back to Saudi Arabia in 2006, went back to Al Watan, and then got fired again four years later for an article attacking the Saudi religious police.

After that and a number of journalistic ventures, including one involving Qatar, Saudi Arabia’s adversary among the Sunni Gulf states, Khashoggi moved to Washington and began writing articles for The Washington Post that were viewed as subversive by the Saudi authorities.

One person who took criticism as a personal slight was Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Rugman points out that Khashoggi’s espousal of political Islam “would set him in a collision course with his country’s new crown prince, a ruthlessly ambitious monarch-in-waiting”, with dangerous consequences.

The baleful shadow of Trump would remain over the grim tale that followed: Khashoggi’s hounding, killing and the attempted cover-up of the killing

But it was a mild criticism of Donald Trump which led to Khashoggi being ordered to cease his journalism. The order came from Saud al-Qahtani, who was rising to become the right-hand man of the crown prince.

The baleful shadow of Trump would remain over the grim tale that followed: Khashoggi’s hounding, murder and the attempted cover-up of the killing. On a wider ambit the statements made by the US president were seen as giving the Saudi government impunity in pursuing its enemies.

Qahtani, for his part, would be accused of being involved in, even instigating, the excesses of the crown prince and the man who led the execution plot.

Rugman, an accomplished and experienced foreign correspondent with Channel 4 News, follows Khashoggi’s decision to break the ban and start to write columns for The Washington Post that often attacked the kingdom’s policies. On the crown prince he was critical, but also praised the reforms he was carrying out. But there was vicious trolling of the journalist, accusing him of being a traitor, by a media unit set up by Qahtani with extensive use of bots, to counter the kingdom’s perceived foes.

There were also requests for Khashoggi return to Saudi Arabia with offers of lucrative jobs, often from Qahtani.

Khashoggi heeded warnings from friends and colleagues to ignore the enticement. Others had fallen into the same trap and been jailed on return. Some had been “forcibly” rendered back and disappeared into the prison system.

But his guard dropped when he needed a divorce document from the Saudi authorities to marry a young woman he had met, Hatice Cengiz. This was to be his third official marriage; another one had been carried out secretly in Virginia, without being registered, a few months before. Hatice knew nothing of it: the book does not go into this piece of duplicity on Khashoggi’s part.

Khashoggi was directed to pick up his papers in Istanbul by people at the Saudi embassy in Washington, possibly because they felt they could not carry out abduction or killing in the heart of the US capital there even under the Trump administration.

Rugman describes the murder plot being organised, with the teams of killers including the military doctor with a bone-saw flying in, the killing itself in its shocking detail and the amateurish attempt at a cover-up which followed.

All this had been extensively documented, mainly because the Turks had bugged the consulate and the information was then drip-fed to the media along with public expressions of outrage from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – ironical, one may feel, with his government holding the record for imprisoning journalists.

Donald Trump initially did not dwell much on the murder, then said he was concerned by what happened but nothing much could be done because of the amount of money the Saudis spent buying American arms, exaggerating the figure. The president attempted to brush aside CIA assessments which laid culpability at the door of the Saudi government and concluded that the crown prince was involved.

The role of Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner – whom secretary of state Rex Tillerson and others in the State Department had accused of running his own, private, cack-handed foreign policy – had come under scrutiny because of the friendship he cultivated with Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Kushner has been accused of approving the prince’s crackdown on opponents, but no definite proof has emerged of this. Earlier this month the magazine The American Spectator claimed that Turkish intelligence had a recording of Kushner approving of Khashoggi’s arrest in a phone call to the prince, and Erdogan used this to force Trump to abandon the Kurds in Syria. But again no proof was offered.

This book also does not offer proof that the prince was involved in the murder. The Saudi position now (it has changed three times) is that the murder was carried out by people in the security apparatus without the prince’s knowledge. Eleven suspects, whose names have not been released, are being tried for the murder in behind-closed-door proceedings in the kingdom. Qahtani is not believed to be among the defendants.

Soon after Khashoggi’s murder, Saudi Arabia held a financial summit in Riyadh, Davos in the Desert. Many heads of states and CEOs stayed away. One who did not was the Pakistani prime minister, Imran Khan. I was among a small group of journalists who asked him about this in Islamabad before he set off.

Khan said that he had no choice because his country was almost bankrupt and he desperately needed Saudi largesse. There was furore in Pakistan – not because he was going, but because he had supposedly humiliated the country by making its economic plight public.

At least Khan was candid. Most of those who boycotted Davos in the Desert are as keen as ever to do business with Saudi Arabia. Rugman’s book quotes a member of the royal family telling The Wall Street Journal that when the trial of the murder suspects ends and “when a few heads get chopped off, [foreign investment] will come back”.

Sadly, he is right: that is very likely to be the way it will play out in the future.

‘The Killing in the Consulate’ by Jonathan Rugman is published by Simon & Schuster (£20)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments