The slow shift in attitudes towards LGBT+ people in Japan

In the only G7 country not to recognise same-sex marriage, where laws around changing gender are also controversial, it’s an uphill struggle for activists, says Julia Mio Inuma

The greys of winter have lingered in Shobara, a rural town in southwestern Japan, where tilled rice paddies look like barren plots of dirt and only the most attentive trees have started waking up to spring.

The dullness makes the one pop of color even more striking: the rainbow flag that hangs outside the home of Kei Okuda, a svelte 62-year-old with a sleek graying ponytail and a bold red lip.

Until transitioning to live as a woman four years ago, Okuda’s life was filled with waves. At their crest, her confusion about her gender identity would be unbearable. The moments of calm at the trough – when the uncertainties would subside – sustained her through a 31-year heterosexual marriage as a father of four.

The marriage broke down for reasons unrelated to her identity, she says. But a few months later, Okuda had a dream that she was a woman – and she woke up in tears of joy, she says. It was an epiphany. When she encountered the term “transgender”, she realised it was what she had been searching for all along.

“When I started to wear dresses and make-up, rather than feeling like I was becoming a woman, I felt like I ... returned to who I really was,” Okuda says. “It felt right, and I finally felt safe in my own skin.”

Still, the transition was not easy, not in her town of about 35,000 residents nor in Hiroshima, the nearest big city. People mocked her and pointed at her. She struggled with thoughts of suicide.

Like many socially conservative Asian nations, Japan remains a hostile place for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people. Social taboos have kept many in Japan’s LGBT+ community largely invisible, fearful to come out to their loved ones or employers.

Japan’s record on LGBT+ issues has come under international scrutiny as it prepares to host the G7 summit in Hiroshima for the leaders of the world’s richest countries. In 2021, Japanese lawmakers were unable to pass a bill to protect LGBT+ people from discrimination. It is now considering a watered-down version that aims to “promote the understanding” of LGBT+ communities but includes no legal protection.

Japan is the only G7 country not to recognise same-sex marriages, and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is facing calls for action. Last month, ambassadors to Japan from the six other G7 countries wrote a joint letter to Kishida, urging him to enact legal protections for LGBT+ communities. Taiwan is the only place in Asia where such marriages are recognised.

But attitudes are slowly shifting toward acceptance here.

We don’t harm others, and we just want to exist and live out our lives. We are not monsters, but just real human beings

About 71 per cent of Japanese people support same-sex marriage, according to a poll conducted in late February by Sankei Shimbun, a right-leaning Japanese newspaper. The support is even more pronounced among the younger generation, with 91 per cent of those ages 18-29 in support.

The majority of Japanese people do not believe the rights of LGBT+ communities are protected, according to a February poll by the left-leaning Mainichi Shimbun.

Several prefectures, including Tokyo, have extended some benefits to same-sex couples. Last month, a Japanese court granted a long-term visa to an American man who married a Japanese man in the United States.

Yet the national government – led by overwhelmingly older, male and conservative elites – has been slow to act, with some politicians actively hostile to gay people, calling them “unproductive” to childbirth. Only one out of the 713 members of the Japanese legislature is openly gay. About one in 10 people in Japan identify as a member of the LGBT+ community, according to a 2020 national survey.

“There is a definite generation gap when it comes to LGBT+ rights,” says Gon Matsunaka, head of Pride House Tokyo, a pro-LGBT+ consortium of nonprofits, corporations and supportive embassies. “When you look at politicians in Japan, the average age is people in their sixties, and most people who are in power in the [governing party] are in their seventies, so we can see why it’s difficult for change to happen.”

Kishida has faced a rocky two months over the issue. In February, he fired an aide for making homophobic remarks, but he also drew criticism for saying he did not think that a same-sex marriage ban constituted “unjust discrimination by the state”.

“The Japanese government will continue to listen to a wide range of citizens’ voices and work diligently to realise a society where diversity is valued and all people can live vibrant lives while respecting one another’s human rights and dignity,” the prime minister’s office said in a statement.

Matsunaka said the time is ripe for action. This is partly because of the growing public support, but also because of a key shift in the political landscape: intensifying scrutiny of an influential conservative religious group, the Unification Church, after the assassination of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, when ties between the group and the ruling party were revealed.

In the meantime, the LGBT+ community remains a target of harassment online and offline. In recent weeks, the trans community has been the subject of online attacks, which have put a spotlight on the legal and social difficulties they face in transitioning.

The number of people changing their registered gender identification rose from 97 in 2004 to nearly 1,000 in 2019. But the process is controversial because Japanese law requires sex reassignment surgery in order for people to change their gender on official records. (Japan’s top court is reviewing the requirement.)

Okuda says there is a lack of support for sexual minorities. The only representations she saw in mass media of LGBT+ people were comedic caricatures on television shows. She didn’t identify with them or the mockery they subjected themselves to for entertainment.

Knowing this, Okuda opened a local safe space for anyone seeking support or who wants to learn about the LGBT+ community. The space, Chosen Family Shobara, is open every Friday. Some days, she has no visitors, and other days, as many as 10 people visit from various parts of Japan.

We have often been considered as these imaginary beings. They talk about us as if it is a new concept that is going to exist in the future, but we already exist

“We [transgender people] don’t harm others, and we just want to exist and live out our lives,” Okuda says. “I want people to know that we are not monsters, but just real human beings.”

Others are similarly working to create supportive spaces for members of the community and raise awareness.

One such effort is Nijiiro Kazoku (“Rainbow Family”), which focuses on supporting LGBT+ families that are trying to navigate legal restrictions and social stigma. The family registry system in Japan is structured such that only one parent in a same-sex relationship can be registered in family records, leaving the other parent with no legal rights to the child.

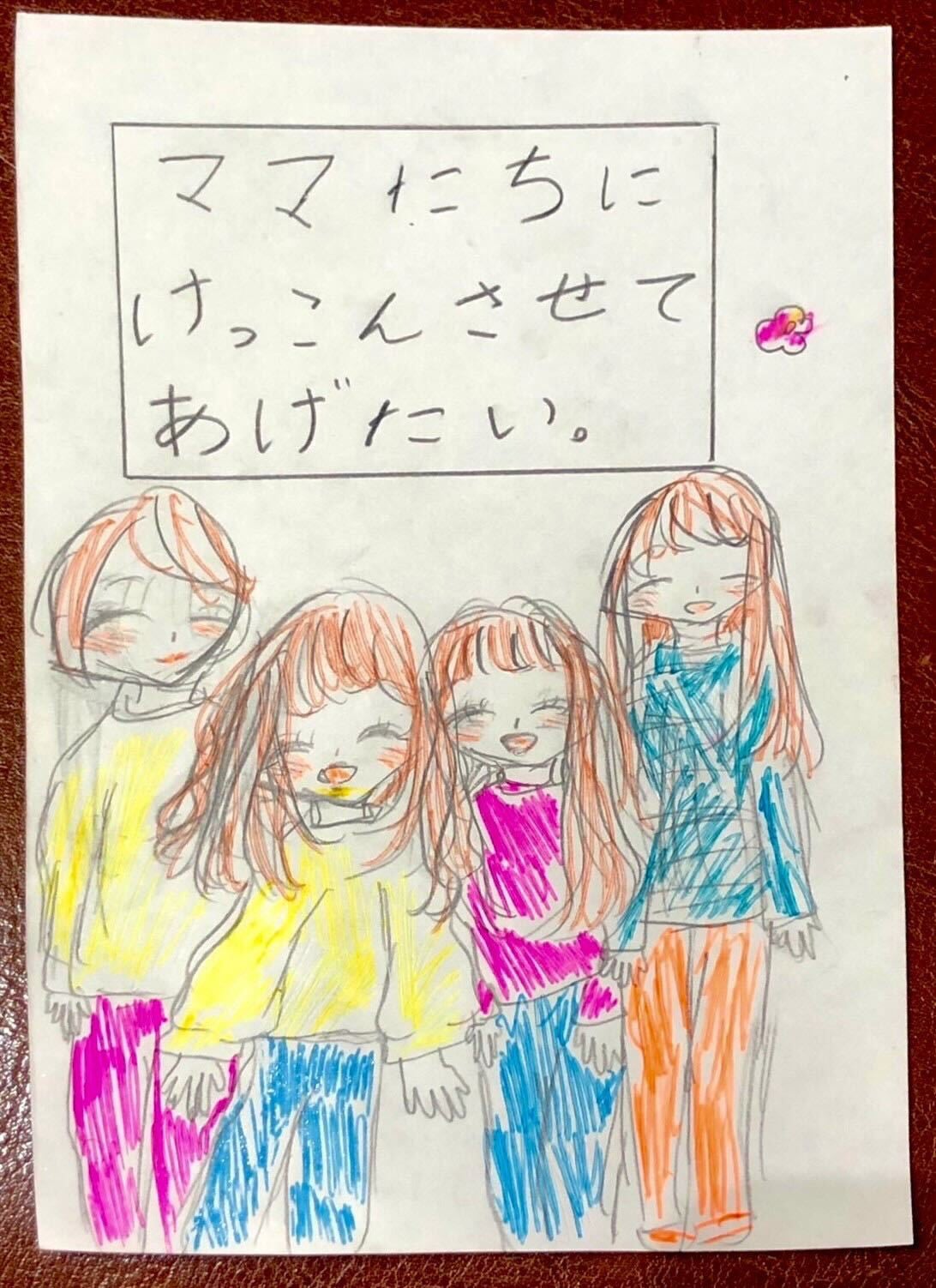

In February, the group organised an effort to get children of LGBT+ couples to write letters to Kishida, urging him to legalise same-sex marriage. Taiga Ishikawa, the only openly gay lawmaker in Japan and an opposition party member, read the letters to Kishida at a legislative session.

“I have 2 moms. They are partners who want to get married but they can’t because of the rule in Japan. Can you please change the rule in Japan, and make same-sex marriage possible?” a first-grader in Osaka wrote in one of the letters. “I would be really happy if you would. The mom who didn’t give birth to me is also my mom. Please let her be in the family.”

A third-grader from Kumamoto wrote: “To Prime Minister Kishida: My house has two moms but I am happy, and our cat and dog are always sleeping happily and eating lots of food.”

Haru Ono, co-leader of the group, says she hopes such testimonies will show the public and lawmakers that LGBT+ people exist in Japan – and deserve equal rights.

“We have often been considered as these imaginary beings,” Ono says. “They talk about us as if it is a new concept that is going to exist in the future, but we already exist, and there are real kids and families right now.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments