‘He had just given up’: The tragedy behind the highly controversial IPP prison sentences

Those who are imprisoned for public protection (IPP) experience anxiety, paranoia, depression and PTSD. They don’t know when they will leave jail and once in the community they don’t know whether they will get recalled, write Samira Ahmed, Konrad Ostrowski, Harry Robinson and Wiktoria Wrzyszcz

Marc Conway looked on with concern at his fellow inmate at HMP Grendon. The prisoner’s fingernails were long and dirty and he refused to shower. Self-inflicted scars showed the physical ramifications of his mental torment. He was an emotionless husk of a man, resigned to his fate.

Both Marc and the prisoner were serving imprisonment for the protection of the public (IPP) sentences; indeterminate prison sentences with no maximum tariff that were introduced in 2003 and abolished in 2012. Marc was sentenced to a minimum tariff of five years and five months for burgling an antique dealer, but was determined to get out on parole as soon as possible. The other inmate, meanwhile, had no fight behind the eyes.

“He had just given up,” says Marc, recalling an image he’s never forgotten, “he was just existing.” The man was a decade over his minimum tariff and had endured multiple parole knock-backs. “He had cut off all contact with family and friends. I’d speak to him and he’d just say, ‘Mate, I’m going to die in prison’. It used to worry me because I’d think, is he going to commit suicide?”

Marc is now out on parole, still serving his life licence and enduring the paranoia of being recalled at any moment. Despite going above and beyond with his sentence to prove he was reformed, Marc still served over two-and-a-half years over his tariff – and he considers himself one of the lucky ones. As of 31 December 2020, there were still 1,849 unreleased IPPs.

“You burn out physically and you burn out mentally,” Marc says of the brutal mental struggle of the sentence. “Lots of people serving IPP prison sentences have severe mental health issues now. It’s the sentence of no hope. I would go as far to say the IPP sentence is the most barbaric sentence, apart from hanging, we’ve had in this country.”

Marc claims the mental impact of being out on licence is greater than sitting in a prison cell. “The licence conditions have made the way I live my life 100 times worse. It was a prison sentence I needed, not a death sentence. You might as well bring back hanging because people are literally hanging themselves in their cells.”

Dr Mia Harris, a researcher investigating the impact of IPPs, explained the mental health burden on prisoners. “IPP prisoners experience anxiety, paranoia, depression, and PTSD,” she says. “They don’t know when they will leave prison and, once in the community, they don’t know whether they will get recalled and for how long.

“1,557 prisoners were recalled due to non-compliance which was the most common reason for recall. People fear the ease at which they could go back to prison, and they know they could potentially stay there until the day they die. This is why the sense of powerlessness and hopelessness is really profound.”

A Prison Reform Trust report shows, between 2015 and 2020, that the number of recalled IPP prisoners grew by 184 per cent. Once released on parole, most prisoners are sent to approved premises (AP) to ease them back into life outside of prison but their residence is far from guaranteed. The AP can withdraw a bed at the drop of a hat, often in the middle of the night. This ruins the risk management plan and results in a recall.

“People felt APs were dangerous,” Dr Harris adds. “They talked about having their possessions stolen, seeing fights, worrying about personal safety. Having to be in a negative environment felt counterintuitive and frustrating, especially for those who had somewhere else to live but were not allowed to stay with family and friends.”

Evidence shows these issues disproportionately affect women, the forgotten minority in a system made for men by men who are spoken about so little. The mental health struggles faced are arguably more intense for women and yet there are no specific guidelines as to how their needs should be considered.

Given the sentence without any real understanding of what it entailed, Tommy began sending frantic and panicky letters home about what the sentence was doing to his mental health

Research by Sarah Smart for the Griffins Society reveals the struggles women have faced. “I’m not minimising male experiences of prison,” she says. “But the pains of prison tend to be exacerbated for women.

“When women enter prison their mental health needs are greater than men’s. A larger proportion have experienced mental health issues and, before they enter prison, a greater proportion of them have experiences of significant trauma, with PTSD or having experienced psychosis.

“We have this very small cohort of IPP women experiencing this on a greater level. It felt like a double injustice and there had never been any research carried out, particularly into female IPP prisoners.”

This lack of exposition defines how prisoners are treated and this has ended lives.

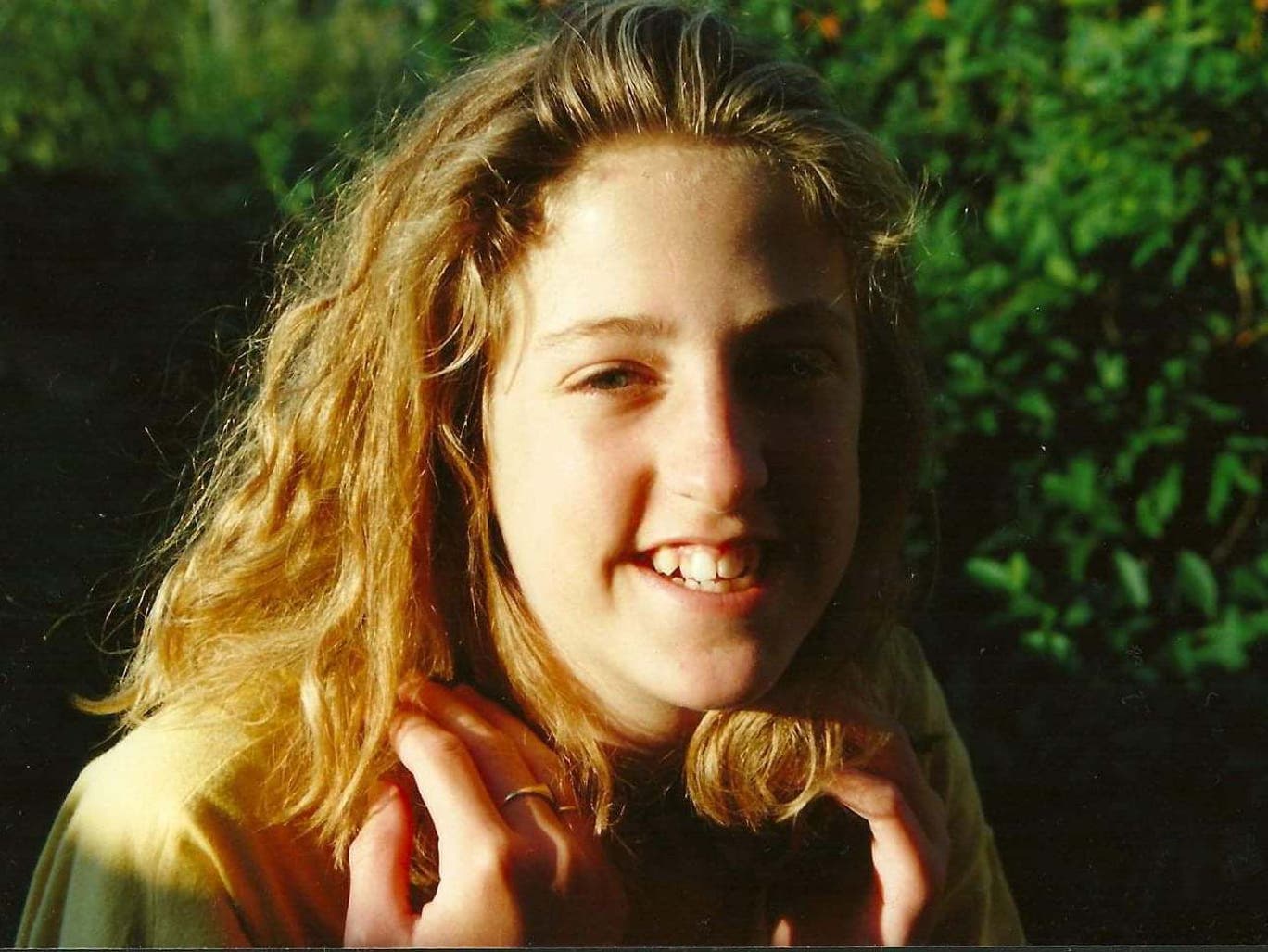

Charlie Nokes was a woman serving an IPP sentence with a minimum tariff of 15 months, convicted of street robbery. She was a supremely creative and talented young woman, and artist. Tragically, Nokes took her own life. The inquest into her death revealed the indefinite nature of her sentence contributed to a sense of extreme hopelessness. She spoke of her sentence as a death sentence. Despite having been seven years over her tariff she was only just getting therapeutic help, without which she had no hope of release.

“She had an art college scholarship for whenever she was released,” Smart says. “She never got to fulfil that dream.”

The mental health impact is evident. A report by the Independent Advisory Panel for Deaths in Custody found there were 35 self-inflicted deaths of IPP prisoners in 2012-2018 alone, with a higher self-harm rate than any other prison population.

Donna Mooney, of the IPP reform group Ungripp, understands the aftermath of IPP sentences far too well. Her brother, Tommy Nicol, was serving an IPP at HMP The Mount for a string of low-level robberies. Given the sentence without any real understanding of what it entailed, Tommy began sending frantic and panicky letters home about what the sentence was doing to his mental health. He was denied places in therapeutic communities – with the system not prioritising IPP prisoners – and was knocked-back repeatedly by the parole board for not being a part of these communities.

As Nicol’s mental health broke down, he was given non-compliance strikes and placed in an unfurnished cell. Prison staff members told him to “behave” as he rocked back and forth and drew circles with his own blood. Nicol hanged himself in 2015, six years into his IPP sentence.

“The system 100 per cent failed Tommy,” Mooney says. “We’ve got letters from him saying it was mental torture. He just couldn’t see a way out. Self-harm and suicide rates are so much higher for the IPP cohort because they don’t have certainty that every other sentence has.”

Mooney feels there needs to be highly trained mental health support introduced in prisons – particularly for those serving IPPs. “I’m trapped in the world of grief of how my brother died,” she says, “and I’m living in that world every day.”

IPP puts a strain not only on prisoners and families, but also parole board members. One such anonymous member, who will be referred to as X, thinks the high volume of recalls is partly due to increasing privatisation of the probation service over the last decade. She believes probation officers are working in a “culture of blame and fear” and often choose to recall too quickly as it’s the easiest option.

Privatisation has decimated the probation service. It has broken excellent members of staff. They’ve haemorrhaged experienced people because of it

“Privatisation has decimated the probation service,” says X. “It has broken excellent members of staff. They’ve haemorrhaged experienced people because of it, and they’re not assisted with resources to be able to do their job. It’s a great shame.”

Despite Amnesty International calling for retrospective assessment of IPPs, the Ministry of Justice forecast the number of IPP prisoners in custody is unlikely to decrease in the next five years.

In response to questioning about the government’s stance on those serving IPP sentences, a spokesperson for Lord Chancellor Robert Buckland says their “primary responsibility is to protect the public”.

They added: “The government is committed to providing IPP prisoners with opportunities to progress and the number of unreleased IPP prisoners has fallen by two-thirds since 2012. As a judge deemed them to be a high risk to the public, it is important that the independent parole board decides if they are safe to leave prison.”

The abolition of IPP sentences in 2012 was welcomed by many, but X feels it was throwing the baby out with the bathwater as it has worsened an already vicious cycle with no way out.

“Regrettably, an IPP sentence means, to all intents and purposes, they are a life sentence prisoner,” she says. “It was a good idea in principle which fell down in practice, due to privatisation, a lack of public funds, judges handing them out willy-nilly where they weren’t necessary and then getting prisoners into custody and failing to fund programmes to help them rehabilitate.

“It comes down to money, I’m afraid. Unfortunately, the public just aren’t interested; all they want to be is safe. As long as criminals are in prison, everything is fine. The average person on the street doesn’t care what happens to them.”

It’s the loved ones who are fighting for change; those outside the cell walls who are serving their own kind of mental life sentence. Mooney and Ungripp are leading the line, helping to free those serving the sentence of no hope.

“I’ve seen the damage it’s done to my family,” Mooney says. “I speak to families all the time and hear the damage that has been done. I hope I’m giving Tommy a legacy. I don’t want his death to be for nothing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments