‘I could well die in here’: The story of Charlotte Nokes and the thousands still locked up on indefinite sentences

Nokes died in prison and her family still don’t know why. Harriet Marsden looks at the complex history of imprisonment for public protection sentences, which kept this woman away from care she desperately needed

This article was first published 20 October 2019. The inquest on 3 March concluded that Charlotte died from natural causes. The jury found that the medical cause of death was “sudden arrhythmic death syndrome”. Charlotte was on suicide watch at the time of her death and should have been checked twice an hour. However, the jury heard that she died several hours before she was found at 08:35 – despite there being checks documented throughout the night.

Her father, Steven, said: “She had many struggles in life, was beaten up for being ‘different’ and experienced mental ill health. Prison was never the best place for her. The indefinite sentence only made this worse. She told us the IPP sentence was really a life sentence, and despite her hopes and dreams of moving to London to study art, she knew she would die in prison. This cannot continue.”

Charlotte is one of four women to have died while serving an IPP sentence. As of June last year, there were still 42 women in prison on the same sentence.

Life is fleeting, life is precious, and I have wasted too much time in oblivion. So wrote Charlotte Nokes while she was a prisoner at HMP Peterborough. She was originally sentenced to a minimum term of 15 months, but by the time she was found dead in her cell on 23 July 2016, she had served more than eight and a half years.

Charlotte had been given an indefinite – and since abolished – imprisonment for public protection (IPP) sentence, one of the most controversial punishments in British justice history. She believed she would never be released, and told her family multiple times that the IPP was her death sentence. She was the first woman under an IPP sentence to die in prison.

In the months leading up to her death, Charlotte was receiving heavy doses of medication to treat her mental and physical health diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (a severe form of premenstrual syndrome). She appeared heavily sedated and could barely talk. But the day before she died, her family say, she was thrilled to have been notified by the Home Office that she would be moved from prison to a therapeutic psychiatric unit as her parole board had recommended. She was still on suicide watch, and was supposed to be checked on twice an hour, but by the time she was pronounced dead at 8:55am the next morning, her body was cold. There was no evidence of suicide.

The inquest into her death began last Monday in Huntingdon Town Hall, and a jury conclusion was expected on Friday. The family hoped to finally have answers as to how Charlotte died, and had secured an expert psychiatric report that examined the impact of the medication Charlotte was prescribed. But the inquest was adjourned until February 2020, because the NHS Trust asked for this evidence to be excluded from the inquest – the coroner denied this request but gave it time to produce their own report. Charlotte’s mother, Sue Anderson, tells The Independent that when the inquest was delayed, she couldn’t stop crying.

“To me, it feels more like a trial than an inquest,” she says. Steve Nokes, Charlotte’s father, says: “It almost seems like a little game of attrition on their behalf.”

Charlotte’s legal team told The Independent the family received some legal aid for representation at the inquest, but were forced to crowdfund the preparation costs, including for the expert report. HMP Peterborough, a private prison run by multimillion-pound company Sodexo, and the Cambridge and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust can afford their own team of lawyers and expert medical reports, while the family will also struggle to pay for the additional work and expenses caused by adjourning the inquest. A major issue in the case is who had overall duty of care: the NHS trust was responsible for her mental health and wellbeing, while the prison and Sodexo were responsible for physical care. In Charlotte’s case, her treatment fell under both remits.

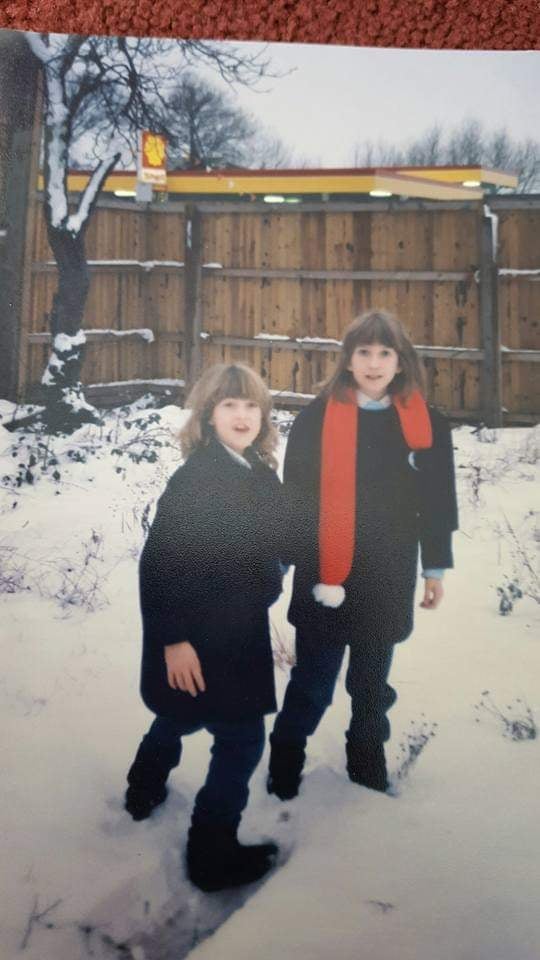

Charlotte Nokes, known as Charlie or Lottie to friends and family, grew up on Hayling Island, off the coast of Portsmouth. The middle child of three, she was clever, funny and creative. Her father describes her as an outgoing child, “very different in lots of ways, always joking around, laughing, a bit of a tomboy”. They used to clean the car, fish, go cycling, and spend a lot of time together.

As a young teenager, she grew bored with her isolated surroundings, starting to smoke, drink and experiment with drugs. Her parents split up when she was 14, around the time she gave up playing football and judo. As a gay girl in a small town, her mother says, she would get beaten up just walking down the road, and began to carry a knife. By the time she moved to Portsmouth at 18, she was addicted to alcohol, heroin and crack cocaine. She began stealing to fund her addiction and racked up more than 50 convictions for petty offences like drug possession and shoplifting. On 27 October 2007, she was begging for money to buy drugs, and when a woman refused, she threatened her with a knife. In January 2008 she was convicted of street robbery and given an IPP sentence, thanks to her spate of prior convictions, with a minimum tariff of 15 months. It was her 30th birthday.

I don’t think you realise how bad this sentence is. I could be in prison for the rest of my life. It’s probably worse than life imprisonment, in the fact that I’ve got no end to it. I could well die in here

IPPs are, in essence, prison sentences without a limit. Created by the Criminal Justice Act of 2003 and put into practice in April 2005 under then home secretary David Blunkett, they were designed to protect the public from dangerous criminals like sex offenders, even if their crimes had not earnt a life sentence. The intention was to use IPP sentences sparingly; the Home Office estimated that they would be used on 900 offenders. But the option was pushed politically, and judges ended up handing them down at a rate of more than 800 offenders per year, some for relatively minor offences.

The offender gets a minimum term, known as a tariff, which they must spend in prison. After that, they can apply to the Parole Board each year for release, but will be set free only if they can prove they are no longer a danger to the public. To do this, they must complete a range of courses or rehabilitative programmes, which are often difficult, or even impossible, to access. Failure to attend, however, could ruin a chance at parole, and prisoners would have to wait another year for a chance again. IPP prisoners also almost invariably serve more than their tariff – many, like in Charlotte’s case, significantly more. The difference between tariffs and time served is often striking.

Nick Hardwick, who was chair of the Parole Board at the time, says that there is a fundamental problem with IPP sentences: they keep people in prison for something they might do in future, rather than what they have done in the past. “The onus falls on the IPP prisoner to demonstrate that they are not a risk, rather than on the state to demonstrate that they are,” he says.

The situation leads to inconsistent sentencing, confusion on behalf of the families of offenders and hopelessness among the inmates. According to Prison Reform Trust figures from 2017, IPP prisoners are among those with the highest rates of suicide and self-harm, almost twice as high as those serving determined sentences. In 2017, David Blunkett told the New Statesman: “I am to blame for IPP, and we would do it differently now.”

Deborah Coles, the executive director of Inquest, the charity that specialises in deaths in custody and is supporting the Nokes family, told The Independent: “There’s no doubt about the cruelty and inhumanity of the IPP sentence in the sense of a complete lack of hope, despair, and being locked into a process. I don’t think it’s difficult to imagine just how much that impacts on your mental health.”

2,315

IPP prisoners are still in custody

She also describes the “psychological torture” felt by families who don’t know when, if ever, their loved ones will be released. “The detrimental harms of these sentences are well known, which is why it’s so outrageous.”

Charlotte’s father Steve says that he didn’t understand the IPP sentence properly at first, and remembers Charlotte saying: “I don’t think you realise how bad this sentence is. I could be in prison for the rest of my life. It’s probably worse than life imprisonment, in the fact that I’ve got no end to it. I could well die in here.”

If they are released, IPP prisoners are put on supervised licence for at least 10 years, often for the rest of their life. Which means that, unless they successfully navigate a labyrinth of bureaucratic procedure, administrative hoop-jumping and probation demands, they can be sent back to prison any time. Steve says that the knowledge of being on licence for the rest of her life was “forever hanging over” Charlotte. “I don’t think it ever went away,” he says.

Charlotte’s mother calls it a vicious circle. “It was just hopeless for her, because she wasn’t getting out, and because of her mental health problems she was misbehaving. There was no way in the situation she was in that she was ever going to get out, ever.”

Hardwick, now professor of criminal justice at Royal Holloway, explains that while some IPP prisoners were recalled because of credible evidence that they posed a serious risk, others had broken only a minor licence condition that didn’t have much to do with future offending. “The barrier to being recalled is too low,” he says. In 2016-17, 760 IPP inmates were recalled, up 22 per cent from the year before.

Andrew Neilson, director of campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform, a criminal justice charity that campaigns on prison probations, has campaigned on the “injustice” of the IPP sentence for many years, and explains that the legislation and guidance around IPP sentences wasn’t crafted sufficiently. “The courts were asked to judge whether the defendant was dangerous,” he says. “A huge swathe of people fell within that definition.”

There’s no doubt about the cruelty and inhumanity of the IPP sentence in the sense of a complete lack of hope, despair, and being locked into a process. I don’t think it’s difficult to imagine just how much that impacts on your mental health

In 2007, the High Court ruled that the sentences amounted to a “general and systemic legal failure”. Overcrowding and lack of funding were pushing prisons to crisis point, and by 2010, there were approximately 10,000 IPP prisoners in the system. When the European Court ruled that they were in violation of human rights, IPP sentences were abolished in 2012 by the coalition government – but not retrospectively. That meant that thousands of IPP prisoners, like Charlotte, were left in jail without a release date in sight.

A joint HMPPS and Parole Board action plan is in place to try to help IPP prisoners to leave, and there are progression regimes at four state prisons across the country, but not for private prisons, like the one Charlotte died in.

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson told The Independent that as of June this year, there are 2,315 IPP prisoners still in custody, and 1,114 who have been released and recalled. That makes a total of 3,429 inmates without a definite release date: 70 are women. The cost to the taxpayer is measurable; the cost to the mental wellbeing of the prisoners is not.

Neilson describes a “Chris Grayling” era of staff cuts that have pushed the prison system to breaking point in the past five years, leading to unprecedented levels of violence. He also reiterates that the Howard League is opposed to privately run prisons. “We don’t think that punishing people should be something shareholders can make a profit out of.” Although, he says, “women die in both private and public prisons, I’m sad to say”.

The year Charlotte died, the number of deaths in women’s prisons reached a record high. She was one of 22, and one of three whose cause of death is yet to be determined.

After a similar spike in 2006, when six women died at Styal prison in a 13-month period, Baroness Jean Corston was asked to review the issue of women in the criminal justice system. The seminal Corston report, published in 2007, found that the vast majority of women sentenced to prison were there for non-violent offences, and were often among the most disadvantaged in society: poor, homeless, addicted, or victims of abuse and trauma.

Coles, who was on the review team, says the report showed how prison had become a kind of “dumping ground for women who could, and should, have been better served in the community, because a lot of those deaths raised concerns about how women were self-medicating for traumatic life experiences, particularly abuse”.

It recommended that the female prison population be dramatically reduced, and that inmates should be held in small, locally run units or therapeutic facilities. The report received widespread support across the political parties, but most of the recommendations have not been put into practice. Austerity measures, like cuts to legal aid and housing benefits, disproportionately impacted women, while more than half of female prisoners have dependent children and are incarcerated hundreds of miles from their families due to a dearth of women’s prisons. According to Coles: “The shocking reality is that there’s always a place for a woman in prison, but there are not enough places in a woman’s refuge or drug and alcohol residential service – but we continue to lock women up.”

Holloway Prison in London, which once housed Myra Hindley and Rose West, was closed in 2016, but the money saved was not invested in the sort of community provision that the Corston report envisaged, such as women’s centres and social housing. “It was an incredible opportunity to do something with that money,” says Coles, “but all those women got shipped out to other prisons which has had serious consequences for the ones from London in terms of access to their families and support networks.”

Inquest released a report on women’s prisons in May 2018, called “Still Dying on the Inside”. From March 2007 to March 2018, 93 women died in female facilities, it concluded, and seven transgender women died in men’s prisons. Thirty-seven deaths were self-inflicted. The front of the report is decorated with Charlotte’s artwork “Perception”.

In prison, Charlotte had developed into a talented artist, supported by charities such as the Michael Varah Memorial Fund and Women in Prison, and painted murals on her cell walls. She was even allowed to decorate other women’s cells. Her work was exhibited by the Koestler Trust, a charity that helps people in detention express themselves. She won several prizes, entering each year from the four different facilities where she was incarcerated. Charlotte had even been offered a scholarship to Central St Martins art school, to be taken up upon her release.

Fiona Curran, director of the arts at Koestler, says that Charlotte’s work showed “an honesty and vulnerability that our awards judges and exhibition curators really responded to”.

In Charlotte’s notes accompanying her submissions, she wrote: “I eat, breathe, live, consume art. I can’t imagine my life without art in it. (I don’t know how I have managed without it in my life previously) ... It has completely changed my life, and my perception of life, and given me something worth living for and working towards getting out (as I am an IPP).”

Charlotte suffered from significant mental illnesses and was on an ACCT care plan, the process in which prisons monitor inmates who they consider to be at risk of suicide or self-harm. She wrote: “I draw within the confines of the cell, or my mind. My cell comforts and keeps me safe and when I am painting I am completely free. I would be a broken woman without this.”

But 18 months before her death, the parole board recommended that she be moved to a secure psychiatric unit, which made her hopeful. Her mother says that the day before Charlotte died, she phoned to say that she was to be moved to a secure unit, and “sounded very cheerful about the whole thing. She would have received the right treatment in there, she wouldn’t have been given medication to shut her up”.

But Charlotte was never moved. When Sue got the phone call from the prison chaplain, her first instinct was that it must have been suicide. “I never thought she would have just died of natural causes, just gone to sleep and died,” she says. “I didn’t expect her to die. She was more worried about us dying and not being there for us. It turned out to be the other way around.”

Gender inequality in prison

The Corston Report, published in 2007 to reform the ways women were looked after in prison, found:

- 30 per cent of women lose their accommodation while in prison

- Prison is disproportionately harsher for women because prisons and the practices within them have for the most part been designed for men

- Self-harm in prison is a huge problem and is more prevalent in the women’s estate

- Women prisoners are far more likely than men to be primary carers of young children and this factor makes the prison experience significantly different for women than men

- Women with histories of violence and abuse are over-represented in the criminal justice system and can be described as victims as well as offenders

- Drug addiction plays a huge part in all offending and is disproportionately the case with women

- Outside prison, men are more likely to commit suicide than women but this is reversed inside

- There were 11 deaths in women’s prisons in 2007, an increase from eight the previous year

According to the Prison Reform Trust, more than twice as many women attempt suicide in prison as men, despite only making up 5 per cent of the prison population. Neilson says that, due to women’s vulnerabilities and concerns around childcare, as well as higher rates of mental health problems and addiction, prison is a “particularly punitive setting to be placed into”, which is why he suspects self-harm rates are as high as they are. “It’s a sign of how poorly women react to prison, which is something that, in the end, was really designed with men in mind,” he says.

As of November 2018, there were 3,807 female prisoners in England and Wales. The Griffins Society published a report this year specifically about women serving IPP sentences, written by Sarah Smart, a fellow of the Women in Prison charity. Each of the nine women she spoke to had served at least twice her tariff, with one serving 11 times more. None of them had fully understood IPP sentences when they were first given them, and all were angry that despite the sentences being abolished, they were still incarcerated. Six out of nine of them had attempted suicide. The report was titled “Too Many Bends in the Tunnel”.

Claire Cain, campaigns manager at Women in Prison and colleague of Smart, explains that the feelings of hopelessness specific to IPP sentences compound the issues that female prisoners already faced – mental ill-health, previous trauma and abuse – to create a situation where female IPP prisoners were doubly impacted. “It’s a catch-22,” she says. “The hopelessness adds to your mental ill-health, your behaviour declines, and you’re moving further and further away from being paroled.

“There is such a lack of trust of women in prison for everyone, through their experience of the state and the system, and recall is absolutely devastating; when you’ve been in prison for a long time you might experience being institutionalised, and if the support is not there for people on release then they just breach their licence and end up back in prison not even for breaking the law.”

Charlotte’s father says that he believes Charlotte did not trust the system to look after her, and that he thought she was beginning to become institutionalised. “I think she thought, ‘if I’m never going to get anywhere, if there’s no light at the end of the tunnel, what’s the use of being good?’”

But worsening prison conditions mean that suicide and self-harm in the male prison population are now also dramatically on the rise, especially among the IPP population. Donna Mooney is the sister of Tommy Nicol, who was sentenced to an IPP in 2009. She campaigns with multiple families of prisoners serving IPP sentences, and voiced her concerns to The Independent about the lack of mental health resources specifically for IPP prisoners.

Tommy was given a minimum tariff of four years, and served six. During that time, Mooney says, he tried to access the therapeutic courses right from the start, but there was “barrier after barrier”: a Kafkaesque nightmare in which Tommy put in applications that were shut down, or was moved prisons, or the system had an administrative error, or he was not told for more than a year that his application did not have enough information. “He was trying his best, he’d not got into any trouble, he was well behaved, he tried to get the rehab, but when he got another knock from the parole board he was put into segregation and just couldn’t cope.”

There is such a lack of trust of women in prison for everyone, through their experience of the state and the system, and recall is absolutely devastating; when you’ve been in prison for a long time you might experience being institutionalised, and if the support is not there for people on release then they just breach their licence and end up back in prison not even for breaking the law

Mooney describes how his mental health deteriorated, and when he was sent to The Mount prison in 2015, he had a psychotic episode. He was cutting himself, sitting in a circle of blood, chanting and talking to the walls. He was moved to an unfurnished cell, with just a mattress on a floor and a pot for a toilet. His mental health team tried to see him during this time, but they were denied access on a Friday and nobody was available on the weekend. On the Monday, the prison guards deemed him too dangerous for visitors, even through a screen. Tommy hanged himself a few hours later. He was 31.

“If you’re not going to change IPP sentences retrospectively,” Mooney says, “you need to ensure you’re providing the mental health resources – particularly for people who are over tariff, and I know that still isn’t happening despite what the MoJ says. The deaths are still happening, the suicides in the IPP population are increasing, a lot of the prison officers have left because of budget cuts or are less experienced than they used to be.”

She says that, because of the possibility of an upcoming election, she does not believe anyone who wants to be re-elected will go on record and say that the IPP population should be released, given the Conservative “tough on crime” stance. Public awareness is low or perception is poor, and people “might not be aware of the injustice of it”. She adds: “The referendum definitely diverted the government’s attention away from this issue, and alongside many others it’s gone to the bottom of the pile.”

Cain, too, blames the “churn” in ministers and secretaries of state since the 2016 referendum vote. “We go on a journey of educating and supporting ministers to find out what’s going on on the ground, but that takes time, and then they resign over Brexit and we get a new one in.”

Even in the midst of negotiations, the government managed to publish the Female Offender Strategy last year, aiming to drastically reduce the women’s prison population. But Hardwick agrees with Coles: “The distractions of Brexit have taken attention away from dealing with the recommendations I made. What’s needed is legislative and policy changes, and at the moment it’s very difficult to get politicians to focus on anything apart from Brexit.”

Robert Buckland, the justice secretary, Rory Stewart, the former prisons minister, and Lucy Frazer, the current prisons minister, were all approached for comment for this article.

Coles describes a “kind of inertia”, saying: “You get this well-worn mantra that lessons will be learned, but they’re extremely empty words when you see the same issues being repeated time and time again at the inquests of deaths of other women in prison. Change requires political will, and in sentencing policy: that prison should absolutely be a place of last resort.”

Charlotte, she explains, is a clear example: “Prison was the wrong kind of environment for a woman like her, who needed a therapeutic setting. That’s where she should have been. She should never have been in there. The fact that her family are now having to crowdfund to find out how she was able to die in a place where she should have been safe – an extremely vulnerable woman who died where they owed her a duty of care – is absolutely outrageous.”

An MoJ spokesperson explained that, while they cannot comment on individual cases or say anything that might prejudice an ongoing inquest, a joint action plan between HMPPS and the parole board was brought in after Charlotte’s death to help prisoners progress towards release. Four prisons are dedicated to helping IPP prisoners prove themselves safe to the public – but these are state prisons, rather than private.

They added: “Legal aid is available at inquests in exceptional circumstances with more than half of applications approved. We are reviewing the legal aid means testing thresholds to ensure that those who need legal aid are able to access it in the future.”

As to what he hopes for from the inquest, Charlotte’s father says: “All I want is an answer to how she died. On her death certificate – we’ve got a temporary one so we were able to have a burial ceremony – it doesn’t say. I’d like to know if anybody was to blame.”

Charlotte is buried at the sustainability site at East Meon in the South Downs, looking towards Hayling Island. Sunflowers were laid on her grave. Her father said: “I thought the sunflowers seemed very apt, because Lottie was a true artist.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments