Seven decades after its release, why classic western ‘High Noon’ is the political movie of the century

It’s about an intrepid loner tackling the forces of darkness and has a veritable Mount Rushmore of presidential fans. Seven decades after its release, James Rampton explains why Hollywood classic ‘High Noon’ isn’t just a great western — it’s an enduring symbol of the struggle for American democracy

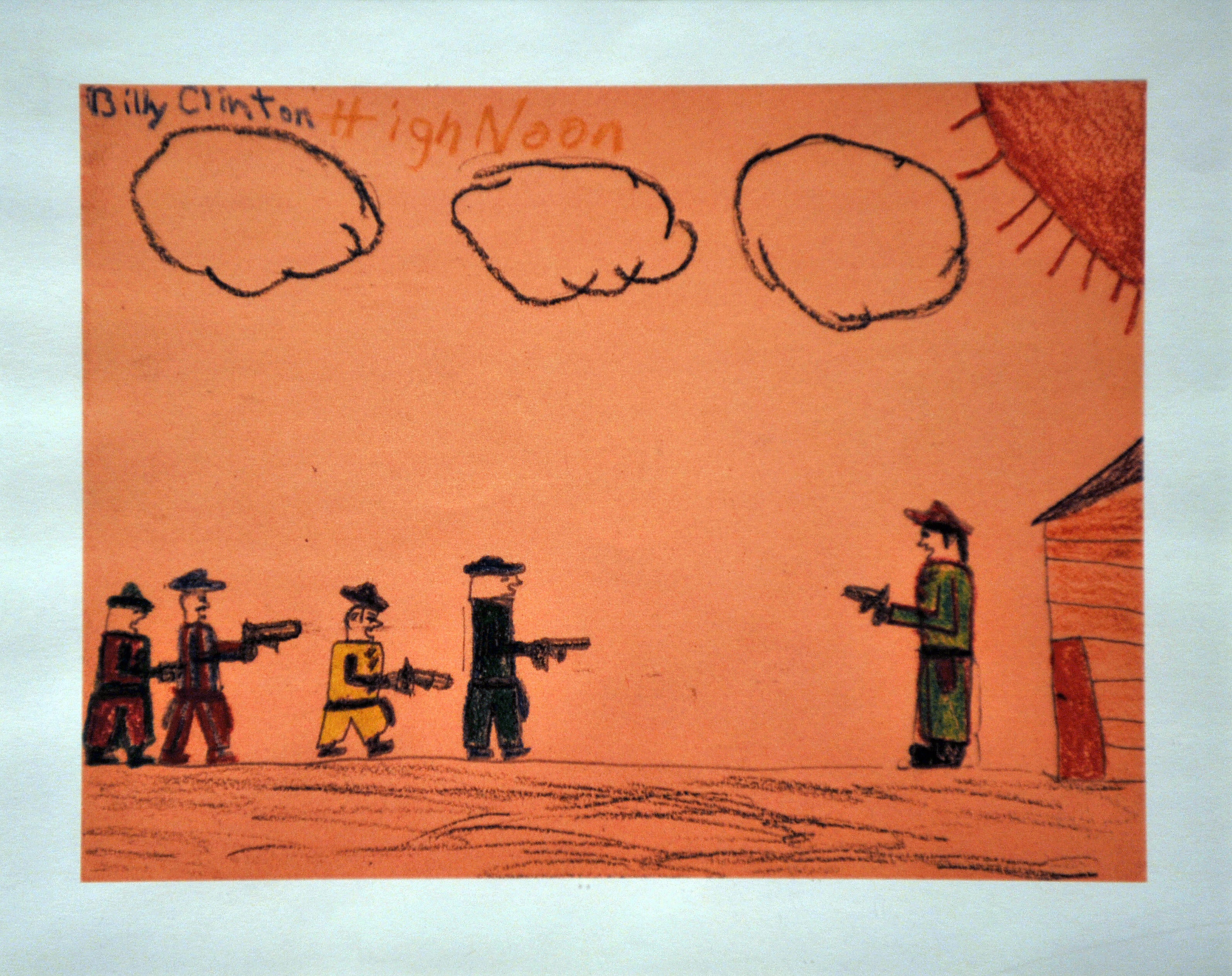

High Noon is President Bill Clinton’s favourite film. To prove the point, he screened the movie a record 17 times at the White House. By now, he may well know the script better than the film’s star Gary Cooper ever did.

The classic western – in which the ageing, newlywed marshal Will Kane, played by Cooper, stands alone as he takes on a gang of ruthless criminals while all his supposed friends melt away – was also the favourite film of such diverse US leaders as Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan and George W Bush. High Noon has a Mount Rushmore full of presidential admirers.

But they are not the only aficionados of what is regarded by many as the greatest western ever made. The Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day Lewis, for instance, has declared: “I love the purity and the honesty of the film. High Noon means a lot to me.”

The movie, which was scripted by Carl Foreman, is still so universally popular that its title is now used to describe any moment of high political tension where an intrepid loner tackles the forces of darkness.

Last year, for example, the congresswoman Liz Cheney, one of the few Republicans with sufficient courage to stand up to Donald Trump in the wake of the 6 January 2021 riot at the US Capitol, was depicted in The Economist as Will Kane.

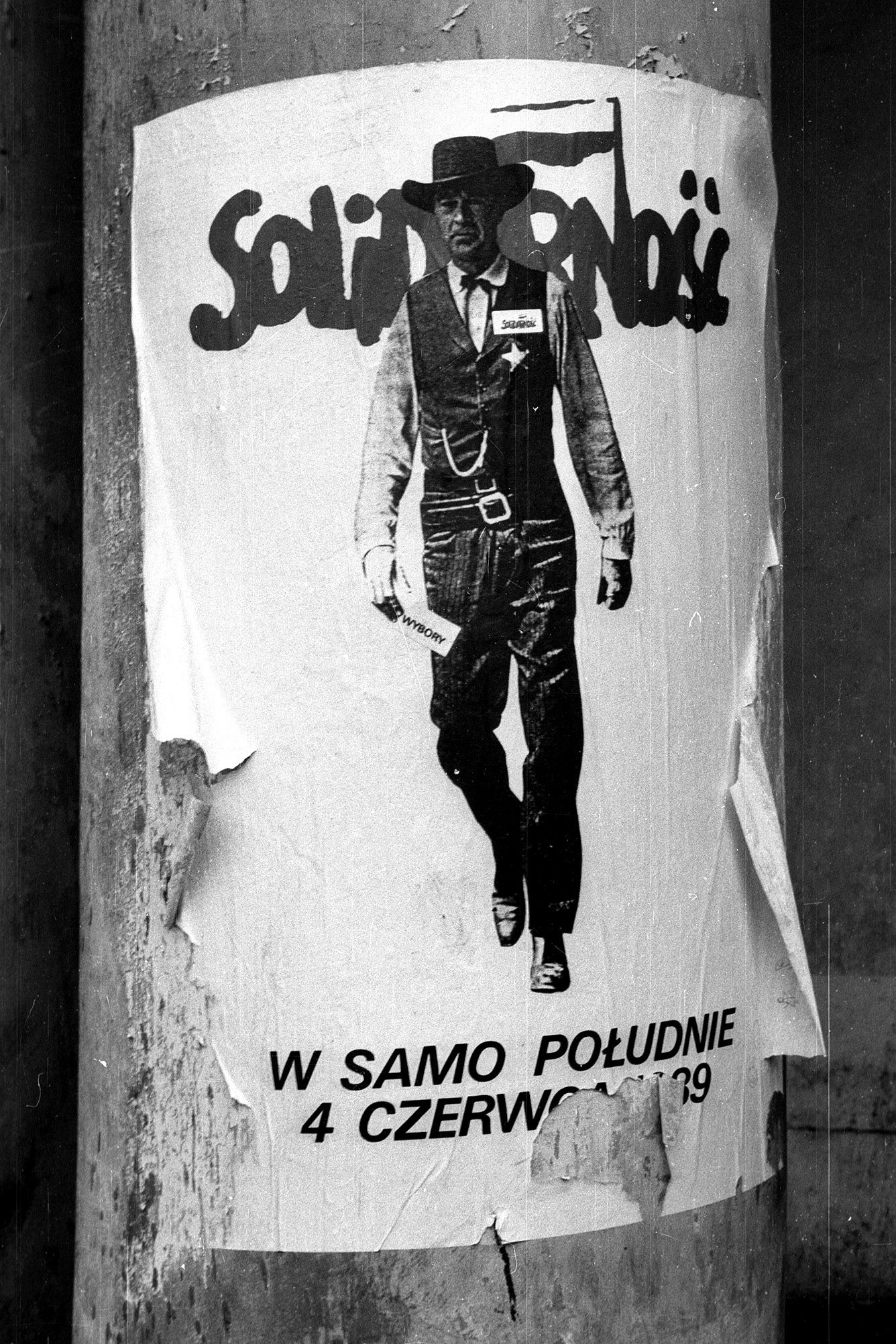

The film has been employed in the same way by political movements across the globe. At the height of Lech Walesa’s principled stand against the might of the Soviet Union in Poland during the late 1980s, for instance, posters for his Solidarity movement featured the silhouette of Will Kane.

Cooper’s daughter, Maria, thinks the movie, “Probably resonates with all of us who have had many high noons in our lives.”

Seventy years after Cooper won one of the movie’s four Academy Awards, then, why is High Noon still so beloved? What is it about the movie that continues to connect with us across the decades?

The principal reason is that it is not merely a simple, superb western. It is freighted with potent political ideas that still strike a chord today.

John Mulholland, who wrote and produced Inside High Noon, an excellent new PBS America documentary about the movie, outlines its enduring power: “If all High Noon were was a very well-acted, a very well-written and a very well-directed western, it would not have the reach that it has. There are aspects to the script that go well beyond the main plot.

“It’s a wonderful movie, a great suspense story that builds beautifully. But that isn’t its real main thrust. Carl Foreman, the screenwriter, was getting at something much, much deeper and much more fragile in American democracy, and that is: who is going to stand up for democracy? Democracy is merely words on a paper unless someone stands up and defends those words. High Noon’s all about that.”

It is indeed a compelling allegory about a hero who boldly protects his community at the very moment that community drifts away from his side in the most cowardly and self-interested fashion.

High Noon remains remarkably topical in its treatment of a self-satisfied democracy taking its freedoms for granted. At one key moment in the movie, the angry bar owner dares to speaks the truth that the town’s pusillanimous citizens don’t want to hear: “Kane will be a dead man in half an hour and nobody’s going to do anything about it. And when he dies, this town dies, too.”

The film echoes the spirit of “First they came...”, the famous 1946 confessional piece by the German Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller about the German people who chose to look the other way when the Nazis began persecuting their fellow citizens.

This theme really speaks to Clinton. “Here’s a man who’s just got married. He’s done his duty. He wants to lay down his responsibilities, go off with his wife, who’s a Quaker, and make a new life.

“And yet he knows that if he goes away, this thug and his gang will take over the town and crush the decent people who aren’t strong enough to stand up to him. Nobody can stop it but him. But even when he can’t get any help, which terrifies him further, he stays and he does the right thing anyway. That’s the greatness of the movie.”

There are other strands to the concept of what happens when you fail to support your community present in the film. For example, the director Fred Zinnemann, brought his own sensibilities to the production.

Stephen Prince, emeritus professor of Film Studies at Virginia Tech University says, “Fred Zinnemann came to the film with his own set of experiences as an Austrian Jew who was troubled by the rise of fascism in Europe. He could find in this script a potent treatment of a community in crisis, a community that doesn’t respond to the dangers that surround it and, by not responding, forfeits its democratic institutions.”

Another reason why the film is regarded as such a masterpiece is because it is an audacious critique of senator Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and its ruthless probe into the purported communist infiltration of the Hollywood film industry.

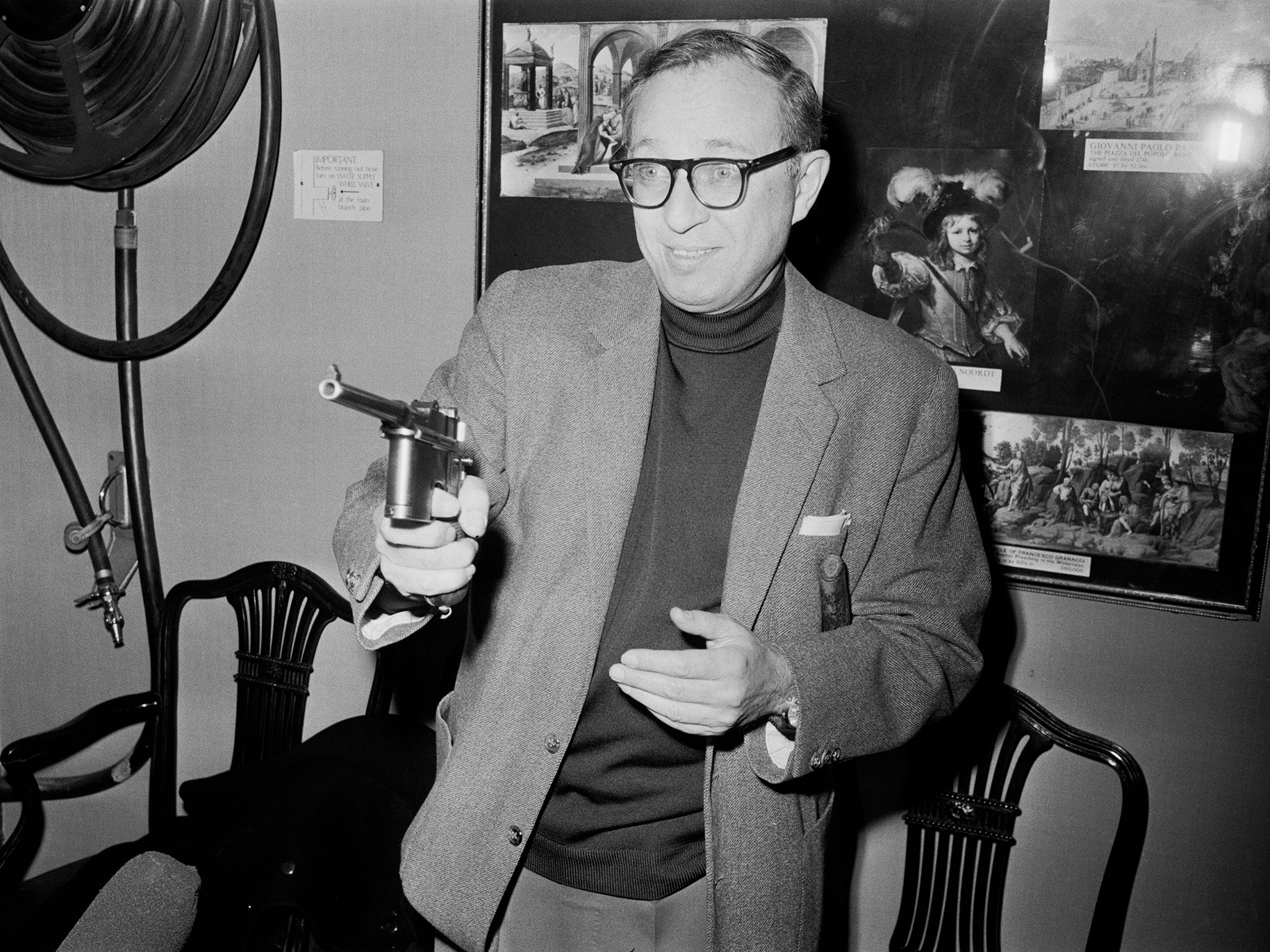

At least half a dozen people working on High Noon were blacklisted, among them cinematographer Floyd Crosby. However, the most famous blacklisted person on the movie was Foreman, a former member of the Communist Party.

He was being investigated by the committee while he was scripting High Noon, and so he rewrote it as a parable about HUAC’s pernicious activities.

Perhaps because of the involvement of these blacklisted people, all the major studios turned down High Noon. In addition, stars of the magnitude of Gregory Peck, Kirk Douglas, Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and Charlton Heston all rejected the role of Kane before the producers came up with the inspired casting of the apparently seen-better-days Cooper.

Mulholland reflects on the pertinence of what Foreman was writing about. “High Noon is about taking a stand. And when you do that, those around you will not step forward if it means putting themselves in jeopardy.

“That happened to Carl Foreman. Once word got out that he had been a member of the Communist Party and that he had been subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, his friends fell by the wayside.”

The persecution of Foreman did not end once the movie came out. He was blacklisted by HUAC and had to move to the UK to find work.

John Wayne, a vociferous supporter of HUAC, called High Noon, “The most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life.” Later, he said he would, “Never regret having helped run Foreman out of the country.”

The director Howard Hawks was equally dismissive of High Noon, announcing, “I didn’t think a good sheriff was going to go running around town like a chicken with his head off asking for help and finally his Quaker wife had to save him.” Wayne later claimed that he teamed up with Hawks to make Rio Bravo in response to High Noon.

Wayne and his right-wing friends applied pressure on High Noon’s producer Stanley Kramer to remove Foreman’s name from the movie. However, Cooper and Zinnemann warned Kramer that they would walk off the picture if he did so, and Foreman’s name was kept in the credits.

When Foreman was subjected to even greater public opprobrium, Cooper stood firmly by his friend. Even though the star was a rock-ribbed Republican, he declared that “Carl Foreman’s politics are his business, and his alone. He is the finest kind of American.”

Foreman returned the compliment, asserting that, “‘Coop’ put his whole career on the block in the face of the McCarthyite witch-hunters. He was the only big one who tried. The only one.” The writer went on to offer Cooper first refusal on all his subsequent scripts, including The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Key and The Guns of Navarone.

Jonathan, Foreman’s son, says, “Cooper behaved so well towards my father during the making of High Noon. My father felt that Cooper was exactly the right person for the role. Cooper’s own personality somehow dovetailed with Kane’s in a way that was absolutely right.”

But High Noon’s motifs do not just apply to the early 1950s. It is testament to the film’s brilliance that it is as politically relevant today as it was back then.

Mulholland muses, “I had long been fascinated by High Noon’s reach into the future. I always felt its basic story – a gunfight waiting till high noon and then it’s the last man standing – shielded the real story, which was about civic complacency.

“What happens to a democracy when its citizens don’t step forward and defend it? The more I saw what was happening in America, the more High Noon seemed prescient. It almost predicted what’s happened in America in the last 10 years or so with the election of Donald Trump and the 75 million citizens in this country who continue to support him, while Congress does not stand up to him. High Noon reflects that perfectly.”

The writer-director of Inside High Noon, which goes out on PBS America on Thursday, carries on, “On the surface, each of the citizens in High Noon has their reason for not standing up alongside the marshal. For example, it makes some sense that the man who volunteers as a deputy says, ‘I’ve got a wife and kid. I could die, and they wouldn’t have a father.’

“But if everyone says that, democracy will die. That leads to civic complacency where everyone says, ‘Let the next guy do it’.”

Mulholland believes that what is currently going on in Congress – where no Republican has the gumption to call out Trump – is, “Especially reprehensible. People in Congress are elected not to preserve their own seat or to say, ‘Well, if I do this, I won’t get elected next year.’ That’s not why they’re there. They’re there to defend the constitution. And so many of them have abandoned that.

“It’s about people in Congress knowing better and yet allowing Donald Trump to say what he likes. He’s just been convicted of sexual abuse in a civil trial. And yet his supporters still come up with excuses about why that isn’t so. He’s been impeached twice and they are ignoring it. If we don’t take that stand, then we are a country in very deep trouble. Trump has opened up wounds here in America. I guess we’ve always had them – they’ve just been covered over by a very, very thin sheet of paper. Trump has ripped that paper wide open.”

He continues, “That article in The Economist portraying Liz Cheney as Will Kane was in fact saying that unless people step forward and stand with her, America is going to end up like Hadleyville, the town in High Noon.”

Mulholland adds with a laugh, “The same might be happening in Great Britain now. Some of the stories coming out about Boris Johnson are positively Trumpian. I don’t know who taught who!”

High Noon, which plays out in real time and expertly ratchets up the tension with frequent close-ups on a ticking clock, certainly provides a very useful lesson to politicians.

According to Clinton, “I think what resonates with all kinds of politicians is that Cooper faces apparently insurmountable obstacles and has been abandoned by the people who should be his allies.

“That has a kind of universal appeal, whatever your politics are, because if you’ve ever had a position of responsibility and tried to do anything with it, you know what it’s like to have to make hard decisions that are of uncertain outcome, often without the allies you ought to have.”

He carries on, “It’s no accident that politicians see themselves as Gary Cooper in High Noon – not just politicians, but anyone who’s forced to go against the popular will. Any time you’re alone and you feel you’re not getting the support you need, Cooper’s Will Kane becomes the perfect metaphor.”

Perhaps the chief reason why High Noon continues to chime with us is because it is an extraordinary portrait of valour. Clinton says, “Gary Cooper showed that real courage is doing the right thing when you’re terrified, when you’re fully aware of the consequences.

“He rose above his fear. That’s the universal appeal of the movie because we don’t pretend that he’s some superhero that never had any fear … Fear does not diminish manhood or strength, if you face it, turn onto it, own up to it, and then go beyond it. That’s the genius of the movie.”

Clinton concludes, “High Noon has stayed with me for over 50 years now, enriched my life and reminded me that courage is not the absence of fear; it is perseverance in the face of fear.”

Finally, Mulholland reflects on the impact he hopes Inside High Noon might have on audiences. “I hope that it opens up something in people.

“I hope they’re saying to each other, ‘I just thought that it was a western. I didn’t think that it was about standing up for democracy’.”

Inside High Noon is on PBS America on Saturday and available now on demand via Freeview Play

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks