A hero or a conman? Unravelling the mystery of my grandfather’s life

William Cook has spent decades tracing the story of his grandfather, who he grew up being told was the type of man nobody should aspire to be. But then he found out about an act of true human kindness

My grandfather, Werner von Biel, was born in a huge white house called Schloss Zierow on the Baltic coast of Germany, a few years before the First World War. I never met him. When I was growing up, his name was rarely mentioned, and only ever in the past tense, so I assumed he must have died before I was born.

Later, I learned that when I was a child, he was actually still alive. Yet by the time I made that discovery he really had died, suddenly, in another country far from home. He fell out of a train in Switzerland. The police said it was an accident, but my grandmother believed he might have been murdered. This is his story, or rather the story of the things that I now know.

Werner was the seventh and youngest child of Karl von Biel, the Freiherr (or baron) of a rural estate in Mecklenburg, one of the remotest parts of Germany. Bismarck said when the world ended, he’d go to Mecklenburg, because in Mecklenburg everything happens a hundred years later. As a fairly frequent visitor to Mecklenburg, I can confirm that his quip still holds true.

I picked up what little I could about Werner from the only person in my family who’d really known him, my German grandmother, Uschi. As his first wife, and the mother of his three children (of whom my father was the youngest), she knew a good deal about Werner’s early life, but she was loath to talk about him. He’d been in debt. He’d been in jail. She’d divorced him in 1941, and that should have been the end of it, but a few months later they got together again one last time, shortly before Werner was sent away to fight for Hitler’s Wehrmacht. My father was the result.

During the 1930s, Werner and Uschi had lived in Berlin, but when Werner went to jail (he sank his yacht in an insurance fraud) she went back to Hamburg, her hometown. When the Second World War began, Hamburg soon became one of the most heavily bombarded cities in Hitler’s Reich. Pregnant with my father, and desperate to get away, Uschi went to stay with her sister, who lived in Dresden – commonly regarded (correctly in the short term, incorrectly in the long term) as the safest city in the Reich. In 1942, in her sister’s house on the outskirts of Dresden, she gave birth to my father. By now Werner was far away, fighting for the Wehrmacht in Greece. My grandmother and my father survived the destruction of Dresden in 1945, and at the end of the war they made it back to Hamburg. Uschi took Werner’s three children to London and married Gerry Cook, a journalist.

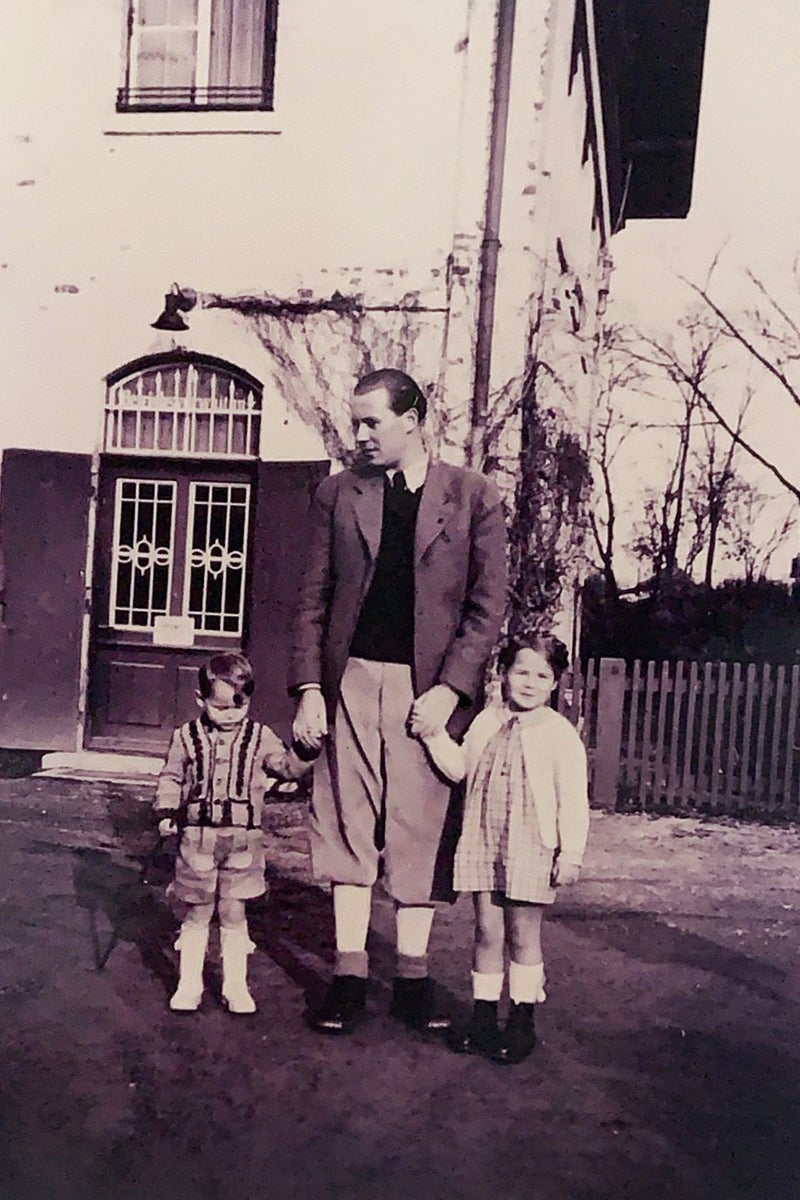

During my childhood that was pretty much all I knew about Werner von Biel, but then in 1989, the Berlin Wall came tumbling down and Germany was reunited. After 40 years behind the Iron Curtain, Mecklenburg had opened up again. I sailed from Harwich to Hamburg and travelled on by train to the ancient Hanseatic port of Wismar, on the Baltic, where I caught a bus to Zierow, and found my great-grandfather’s antique Schloss, at the end of a long avenue of linden trees. I’d never seen a picture of it, so I didn’t know what to expect. From a distance it looked spectacular. A neoclassical mansion, surrounded by lush green meadows, it was much bigger than I’d imagined, and far grander too.

Close up, Schloss Zierow wasn’t quite so smart. The grounds had become a technical college. The Schloss had been stripped of its contents and converted into classrooms. The interior was shabby, but the exterior was still beautiful. In the stairwell was a stained-glass window which bore the same heraldic crest as the crest on my grandmother’s cutlery.

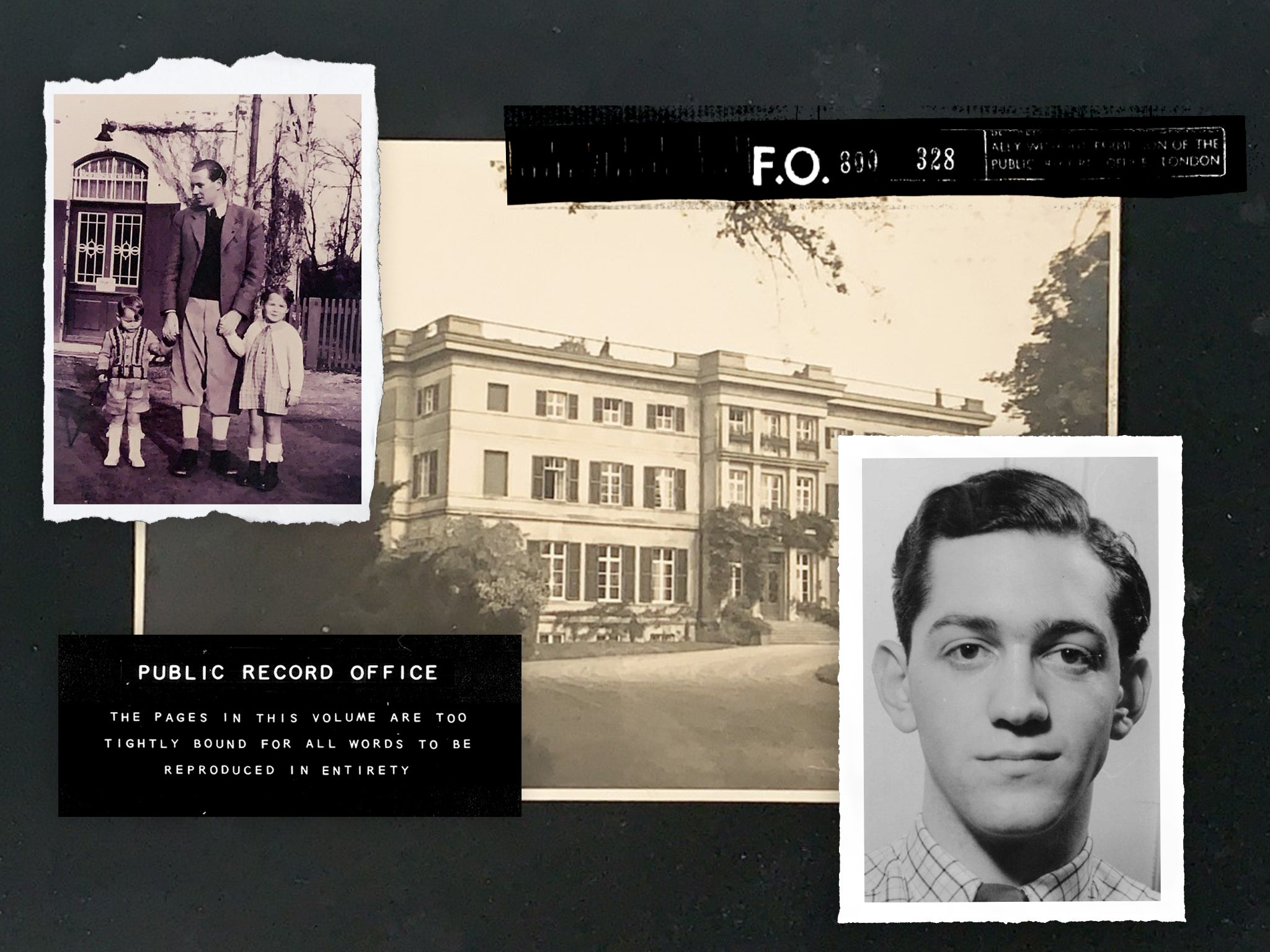

The gardens had been given over to a cluster of brutalist classroom blocks, but the woods and fields beyond had been preserved. In the stables was a small museum, devoted to the history of Zierow. A Soviet-era display chronicled the liberation of the estate, its conversion into a collective farm. The curator apologised for the propagandist nature of this exhibit. I told her not to change a thing. She opened a desk drawer and handed me a folder full of photographs: photos of my great-grandfather, my great-grandmother, and their seven children, including Werner. It was the first time I’d seen a photo of him. He looked a lot like my father. He didn’t look anything like me.

During the 1990s I travelled all over Germany. I found the cosy house in Dresden where my father was born, and the grandiose villa in Hamburg where my grandmother used to live. I tracked down two of Werner’s nieces, Maria and Armgard, who’d both grown up in Zierow. They were the daughters of Werner’s eldest brother, who’d inherited the estate. Their brother could have claimed it back, but they said he had no interest in it. It would cost a fortune to restore, and anyway, what would he do with it? They’d fled to the West after the war and made new lives in West Germany.

In 1999 I got a call from a woman called Erika von Biel, who turned out to be Werner’s second wife, his widow. She was going to be in London for a few days. She wanted to meet up.

Erika had been born in 1925, in that German-speaking part of what was then Czechoslovakia, known to Germans as the Sudetenland, whose annexation by Hitler was one of the main stepping stones on the road to the Second World War. After the war, Erika ended up in Munich, where she met Werner. He was working in a hotel.

Erika told me more about Werner’s early life. Growing up in Zierow, he’d never got along with his eldest brother, Heinz, and when their father, Karl, abandoned their mother, Anna, and ran off with a Hungarian woman half his age, Heinz became the Freiherr, lord of the manor, and Werner’s position became unbearable. He went to Berlin and got some sort of job in the aircraft industry, but after he married my grandmother, Uschi, who bore him two children (my aunt and uncle, Marion and Michael), he started living beyond his means, hence the insurance fraud which had landed him in jail. Erika told me a lot I didn’t know, but there were some big gaps. She didn’t marry Werner until 1967, less than five years before he died.

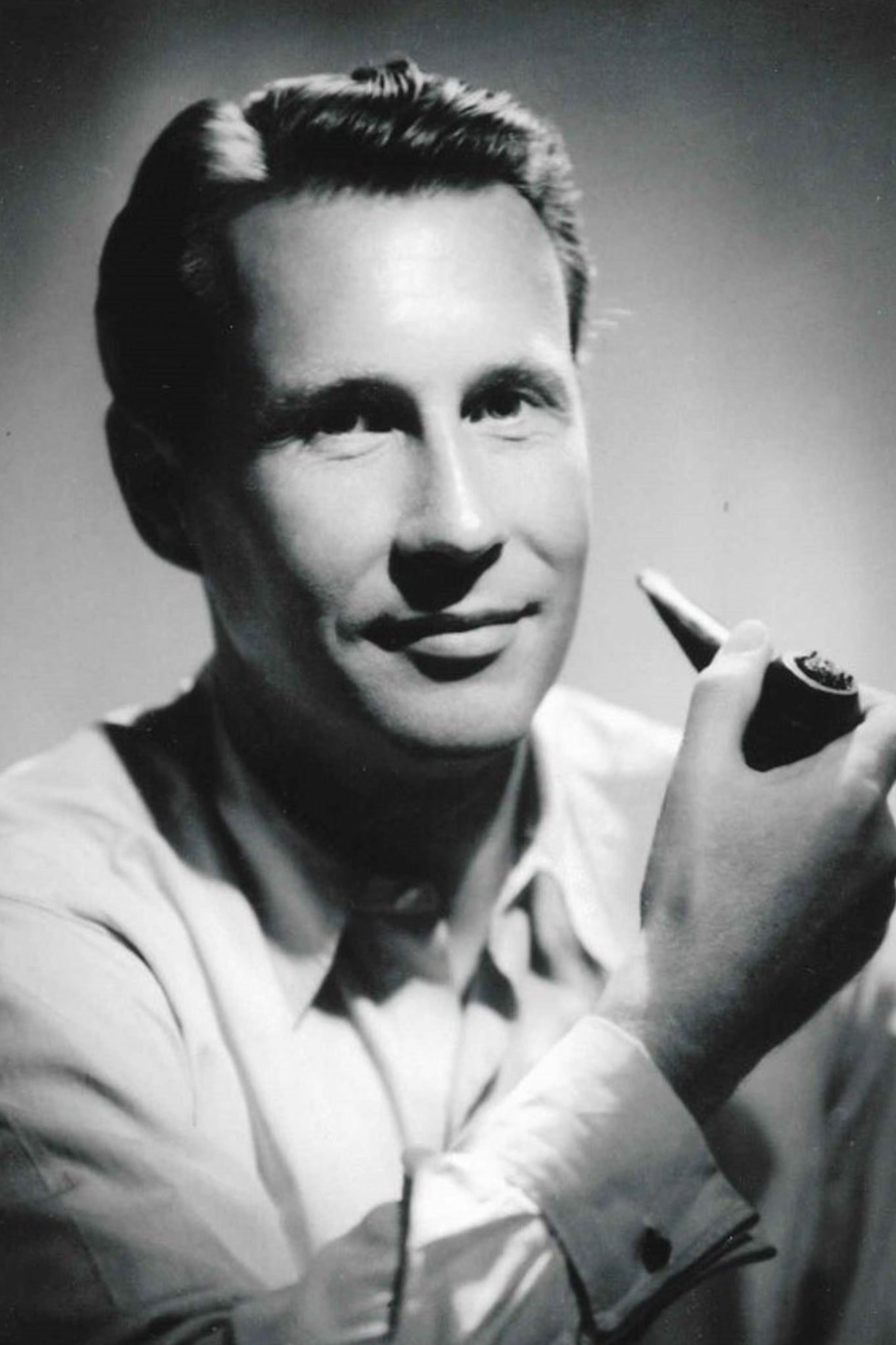

Werner had only just turned 60 when he died, and he was in good shape, fit and healthy. Erika showed me a photo of the two of them, taken on a hiking trip the summer before he died.

Erika told me that for a long time, Werner had been looking for some missing money, money his father, Karl, had put in a Swiss bank account before the war. Karl had died during the war, in peculiar circumstances. Some of his relatives had told me he’d been compelled to shoot himself – handed a loaded revolver, after he’d spoken out against Hitler. It sounded far-fetched, but such things weren’t so unusual during the Third Reich. Whatever happened, when Werner came home from the war, Karl was dead and buried, and his Hungarian widow had only the vaguest idea where his money might be. Apparently, Werner had been looking for it, off and on, ever since.

On the day he died, Werner had been on a train between Munich and Zurich, where he’d gone (or so he’d said) to meet a man who might know something about that missing money. His body was found beside the track in St Gallen, a Swiss town near Lake Constance, not far from the German border.

Erika wouldn’t hear a bad word said against Werner. I told her Uschi never had a good word to say about him. Erika was indignant that my grandmother had been so damning about her husband. Werner was a hero, she said. In Berlin, during the war, he’d sheltered a German Jewish man from the Nazis, called Manfred Alexander. Werner hid Manfred in his apartment, she said, and helped him flee to Switzerland. That was the sort of man he was. Had Werner told her this story? I asked her. Not at all, she said. He’d never spoken about it. She’d heard it from Manfred himself, when he came back to Germany for a visit, as a guest of the German government

The German authorities had asked Manfred if there was anyone he wanted to meet in Germany. Yes, he told them. He’d like to meet the man who’d saved his life, Werner von Biel. The authorities looked into it, found out Werner had died, and proposed a meeting with his widow. Is Manfred still alive? I asked. Yes, said Erika, and gave me his telephone number in New York.

When I got home that evening, I phoned the number Erika had given me. Manfred answered straight away. Yes, everything Erika had told me was true, he said. He’d got to know Werner in Berlin in the late 1930s. He’d never met Uschi, or Marion and Michael, my aunt and uncle. He didn’t know Werner had been in jail. If I came to New York, would you be willing to meet me, I asked Manfred. Of course, he said. A few weeks later I was sitting in his modest walk-up apartment in Queens, listening to the story of his great escape, and his friendship with my grandfather.

Manfred’s story was even more remarkable than the one Erika had told me. He’d dreamt of being an architect, until the Nazis barred him from further education, whereupon he became a bricklayer, a trade which saved his life. He’d been deported in 1941, along with his parents, to a concentration camp in Minsk, where he was put to work rebuilding the train station. Remarkably, his German foreman, a man he would never see again, took pity on him and helped him stow away on a troop train full of wounded soldiers returning to Berlin. He had to leave his parents behind. They were both murdered. When the Germans retreated from the camp all of those still held there were killed, more than 50,000 people in total, 16,000 on a single day.

Back in Berlin, Manfred went to Werner’s apartment, on Grolmanstrasse, where Werner hid him and clothed and fed him. After he’d rested up for several weeks, Werner helped him find some people smugglers who smuggled him into Luxembourg. From Luxembourg, Manfred hiked to Besançon, in France, near the Swiss border, where a blind priest hid him in the crypt of his church. “How did he know that he could trust you?” I asked Manfred. “He felt my face,” said Manfred. “He said that by feeling the contours of my face, he could tell I was telling him the truth.”

From Besançon, Manfred made it across the border into Switzerland. His elder brother had emigrated to New York before the war, and he was able to arrange Manfred’s safe passage from Switzerland to America. Manfred’s survival depended on three men – his German foreman in Minsk, the French priest in Besançon, and my grandfather in Berlin. I met up with Manfred several times thereafter, on subsequent trips to New York. Manfred said he’d like to provide a lasting memorial for Werner. Had I heard of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Israel? They gave a Righteous Among the Nations medal to those who’d helped Jews survive the Holocaust. Maybe we could ask them to grant this medal to Werner, posthumously? I was touched that Manfred wanted to try. He was in his eighties, and in poor health. I said I’d help him all I could.

The last time I saw Manfred was in 2005 at the Israeli consulate in New York, where we received the Righteous Among the Nations medal on Werner’s behalf. The Israeli and German ambassadors were both there. Manfred made a short speech. “Naked a man comes into the world, and naked he leaves it,” he said, quoting a medieval Talmudic scholar called Rashi. “After all his toil, he carries away nothing – except the deeds he leaves behind.”

Later that year, I went back to Zierow. I phoned Manfred while I was there. He said how Werner often talked about the place, how he would have loved to take him there. That was the last time I spoke to him. He died a few months later. I still have Werner’s medal. On it is inscribed: “Whoever saves one life saves the whole world.” When I first set out in search of Werner, I used to dream of finding that money his father Karl had stashed away. This medal was treasure of a different kind.

Back in Britain, I phoned the police station in St Gallen and got them to look up Werner’s file. There was one interesting revelation. They’d tested his blood for alcohol and drawn a blank. He hadn’t had a drink. Maybe after a few beers, a man might take a tumble and fall against a faulty door and fall out onto the track. But a man who’s stone-cold sober? I can’t see it. I also couldn't wrap my head around the idea of suicide. And yet murder seemed even more implausible. The most probable explanation was the most boring one, the one the authorities had settled on. The case was closed. Time to move on.

There’s a strange coda to this story. I got an email from a Russian journalist working in Riga. He’d been investigating the case of the missing Romanovs – an endless tangle of conspiracy theories, based on the supposition (still believed by some, though resoundingly refuted) that one or more of the tsar’s children somehow escaped the grisly execution of the tsar, the tsarina and their five offspring in Yekaterinburg, in Russia, in 1918. He’d been digging in the archives, and Werner’s name had come up.

The covering letter was from the British Foreign Office to the British legation in Vienna. It read like the opening of a Graham Greene novel: “We enclose, for what it is worth, a translation of a document written and handed to us by a certain Baron Biel concerning the present whereabouts of the Archduchess Tatiana of Russia. Baron Biel also approached the US Legation on the subject, but they are not proposing to take any further action on the matter. Baron Biel, otherwise unknown to us, is a German aged about 30 [he was actually 37] who on his own admission has smuggled himself into Vienna to visit his fiancée.”

The document concerned was a long-winded letter from Werner to the British authorities, pleading for the protection of a Russian woman he’d befriended in Berlin before the war, who was currently languishing in a refugee camp in occupied Germany. Werner claimed his friend was really Archduchess Tatiana, one of the tsar’s four daughters.

It was such a tall story, but it was the only letter from my grandfather that I'd ever read. Yet as I turned the final page of this missive, my heart sank. Maybe Werner was concerned for the safety of “Tatiana”. Had Werner been taken in by this woman, or was he in on the conspiracy? Or was he simply chancing his arm, little caring whether this yarn was fact or fiction? The handwritten comments on the file confirmed that the Brits were unimpressed, but they took the precaution of moving “Tatiana” to a different camp. The story got a brief airing in the US press.

Was Werner a hero, a fantasist or a conman? Or a complex mixture of all three? What I’ve learnt from him is that people can be paradoxical – brave and cowardly, naive and cunning, kind and cruel. Werner was all these things, and everyone who knew him saw a different side of him. I reckon I’ve seen every side of him, on his elusive trail these 30 years. I have his medal, and a German passport. And every time I’m back in Mecklenburg, I pay a sentimental visit to his huge white house beside the sea.

William Cook has won several awards for his travel writing about Germany, and the Johann Strauss Gold Medal for his reporting from Vienna

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks