How a caste survey could upend politics in the world’s largest democracy

India’s millennia-old social system has become a target for parties – but will data be used to promote equality, or simply to win votes, asks Karishma Mehrotra

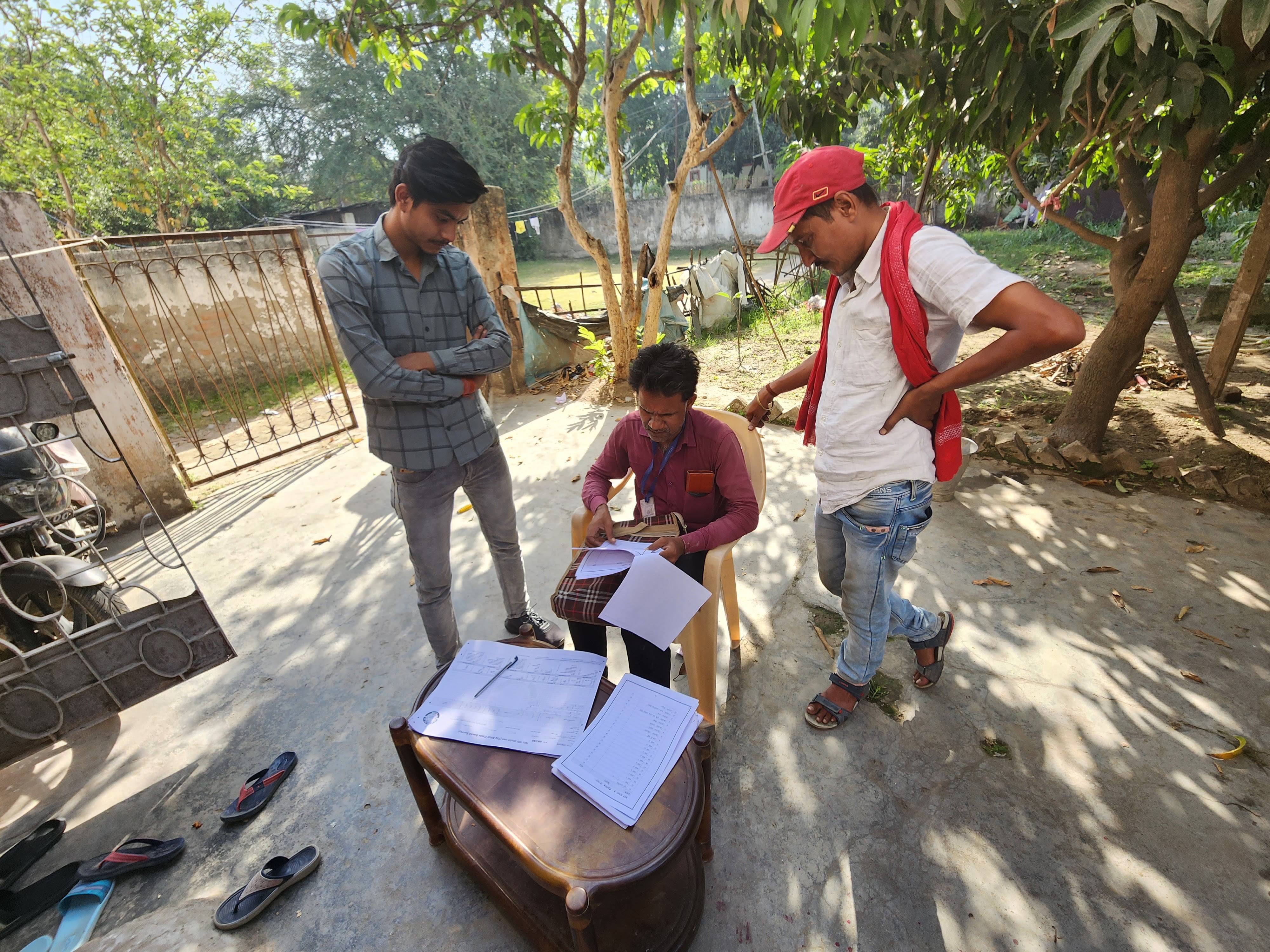

The morning milk is yet to be delivered, but the April heat is already leaving stains on his shirt. Satyadeo Paswan’s brows furrow as he flips through page after page of 215 caste categories, scanning for the correct code to enter in the crucial yet complicated form in front of him.

Paswan is one of the hundreds of thousands of surveyors tasked with an administratively and politically historic exercise: collecting caste data on every single one of the 126 million people in the state of Bihar.

This mammoth task has taken centre stage in Indian politics. A census of caste – the rigid system of inherited social stratification sprouting from Hinduism – could transform the nation’s democratic politics. It puts the governing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in a tight spot: Increased caste identification could dent its electoral supremacy.

Several other states are expressing interest in conducting their own caste surveys and have sought the guidance of Bihar, according to officials here. Nearby Odisha state has begun a version, local reports say. Earlier this month, however, Bihar’s high court ordered a temporary stay on releasing the results while it determines if the state government has the power to conduct the survey.

Critics of the current system say that not acknowledging and studying the role of caste in society ignores the pervasive discrimination that flows from it.

At India’s independence in 1947, the constitution outlawed “untouchability” – the most extreme form of marginalisation against the lowest castes, known as Dalits. But India continued to witness caste discrimination and the maintenance of boundaries dictating who can marry whom, who can eat with whom, and who can do which jobs.

The government has divided the thousands of different castes into three main categories: the Upper Castes; a middle level known as the Other Backward Castes, or OBCs; and the Scheduled Castes, or Dalits, the groups for which India’s first affirmative action programmes were created in an attempt to address their historic marginalisation.

The BJP wants to woo people with a singular identity called Hindu. But that singular identity is not enough to get people food and employment

“The American society fought against racism but such movements in India have been much rarer,” says Manoj Jha, a member of parliament from the Rashtriya Janata Dal, a political party that is part of an alliance governing Bihar. “As a result, the structure is dominated by Upper Castes.”

A renewed focus on caste poses a danger to the governing BJP’s electoral successes and could fragment its umbrella voting bloc of Hindus. “They would prefer to pit Muslims against Hindus as opposed to picking fights within the Hindu community,” says Mamidipudi Ramakrishna Sharan, a University of Maryland assistant professor who has studied caste in Bihar.

Knocking on doors and asking about caste inevitably sparks conversations about the millennia-old concept. “I am a Paswan, but so what?” says the 40-year-old surveyor working in Bihar’s capital city. His own caste falls into the Scheduled Castes, the lowest rung of the government’s categories.

“The same blood in me is in them,” he says, pointing to Alok Kumar – on whose form he was working – as Kumar sits with his friend Kiran Chaudhary. Kumar comes from the Yadav caste, one of the mid-level OBCs.

Chaudhary is a Brahman, from the Upper Caste categories, and expresses a degree of skepticism about the whole process. “This counting is all for politics. They will figure out where all the castes live – not for goodwill but for votes,” he says.

India does not keep exact data on Chaudhary’s and Kumar’s caste categories. After the last British-led census in 1931, the country stopped counting all the caste categories other than the lowest ones.

The push for a complete national caste census dates to 1980 and revolves around the move to extend to the mid-level OBCs the affirmative action programmes that benefit Dalits: reserved places in public education and jobs. Although estimates from the British time show that OBC numbers account for roughly half the population, subsequent court decisions effectively allotted its castes 27 per cent of the coveted spots.

There was immediate pushback from the Upper Castes, and political battles ensued. The OBCs mobilised into new, powerful regional parties – including those that now lead Bihar and have instituted the ongoing caste survey.

The BJP countered these caste-based politics with its brand of Hindu nationalism, and caste and religion have become the two main mobilising forces pitted against each other in electoral battles.

In 2011, the government, led by the now-opposition Congress Party, was reluctantly pressured into conducting a caste survey nationally as part of its decennial census, but it did not release its findings, citing a faulty process. The BJP, when it came to power, continued to withhold the results. Data gathered in another caste survey, in the southern state of Karnataka, also was never released.

“We count tigers. We count dogs. We count trees. Why not human beings and their castes?” says Jha, the member of parliament. “Who is afraid of the numbers? It is the BJP. They want to woo people with a singular identity called Hindu. But that singular identity is not enough to get people food and employment. That singular identity is not without cracks.”

Most analysts say a nationwide count would be likely to show that the Upper Castes were a small minority and that OBCs were much larger in number than their reserved percentages, potentially triggering louder demands for more reserved school and job positions. Some say such a count also could fuel the existing demands for reserved job spaces in private companies.

While the BJP’s core support base has long been Upper Caste groups, it has managed to woo lower-rung segments of the OBCs. “The BJP has been very good at fission and fusion – breaking off its rival’s coalitions and fusing together its own,” says Delhi University’s Satish Deshpande, a sociology professor.

Only the privileged have had the luxury of believing they have no caste

But a detailed census could blow apart the party’s coalition. It’s difficult to “appease” both the Upper Castes and the OBCs, says Himanshu, an associate professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University who goes by his first name only. “The total pie is 100 per cent. Someone would benefit and someone’s share would be cut.”

An adviser in the national ministry of information and broadcasting disputes this representation of the BJP’s thinking. A caste census has “inbuilt problems” of “data collection and data processing,” says Kanchan Gupta.

For the first time, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi of the once-powerful Congress Party last month joined with smaller parties in calling for a caste census, signaling a coalescing around OBC issues in the run-up to the 2024 national election.

Several senior bureaucrats in Bihar who are Upper Caste warned that revising affirmative action programmes would be just as polarising as divisions over religion.

“I don’t see that any fruitful outcome that could come from it,” says a senior Bihar bureaucrat speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue. “It will only lead to another round of agitations [and] intensify the social fracturing.”

Beyond the political quarrels, development and governance experts say detailed caste data is essential for targeted policymaking and resource distribution, especially as sub-castes have progressed in divergent ways.

“How can a collection of socioeconomic data move the country in a backward direction?” says Bihar chief secretary Amir Subhani. “Data can only take the country forward.”

Others say the debate’s narrow political focus on affirmative action programmes misses the importance of the systemwide changes that should be implemented, such as universal access to healthcare, jobs and education. “If you really want to tackle caste, a multiprong approach will be required,” Himanshu says.

For Deshpande, the sociology professor, the drive is for “an official end to this policy of caste blindness.”

“Only the privileged have had the luxury of believing they have no caste. A census acknowledges that not just the lower castes have caste,” he said. A future of castelessness cannot happen “without counting caste”.

Paswan, who usually supervises cleaners in a government building, will take the completed forms he gathered and type the caste numbers and economic data into a mobile application, which Bihar administrators say would have allowed the release of results in the next six months before the next elections – if the court hadn’t stayed the process.

“My family doesn’t believe in caste discrimination,” Kumar says as Paswan finishes collecting his details. “But we know caste is everywhere.”

©WashingtonPost

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments